Andrew Doyle discusses how social contagions of the past resemble the current gender identity boom among western young people:

… social contagions are especially common among teenage girls, and that there are numerous historical precedents for this. I have written elsewhere about the Salem witch trials of 1692-93, in which a group of girls began seeing demons in the shadows and accusing members of their own community of being in league with the Devil. Then there were the various “dancing plagues” of the middle ages which seemed to impact young women in particular. In 1892, girls at a school in Germany began to involuntarily shake their hands whenever they performed writing exercises. And when I visited Sweden last year, I was told about a local village where, during the medieval period, the girls all inexplicably began to limp.

It’s perfectly clear that the latest social contagion to take hold in the western world is that of girls identifying out of their femaleness, either through claims that they are trans or non-binary. Whereas in 2012, there were only 250 referrals (mostly boys) to the NHS’s Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS), by 2021 the figure had risen to more than 5,000 (mostly female) patients. Gender activists like to claim that this is simply the consequence of more people “coming out” as society becomes more tolerant, and at the same time insist that it has never been a worse time to be trans. Consistency is not their strong suit.

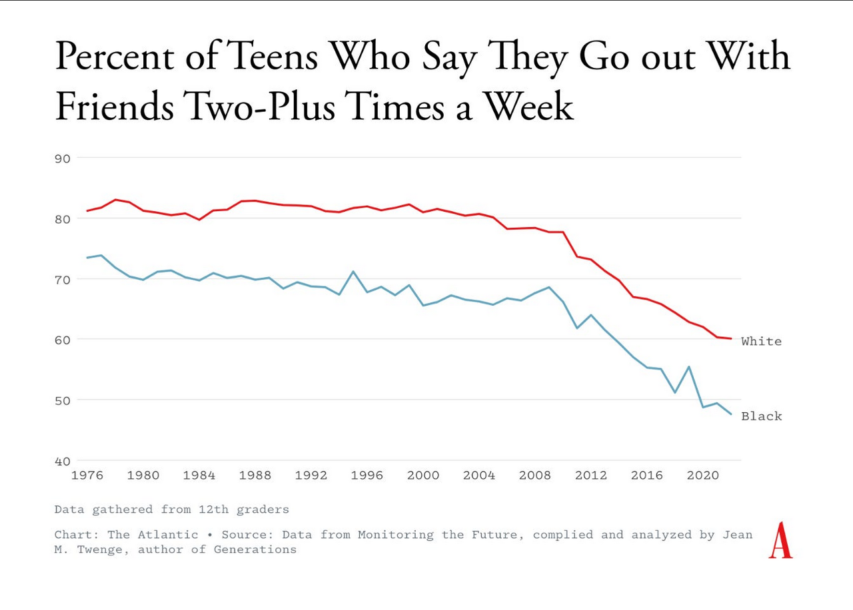

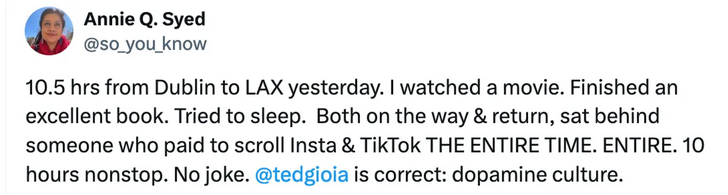

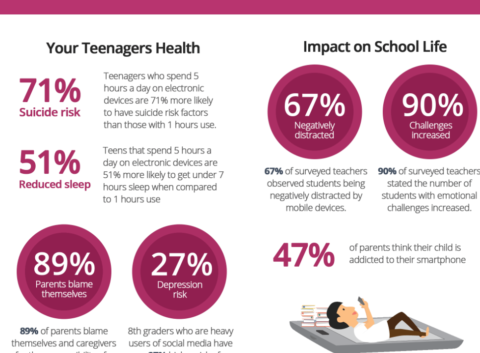

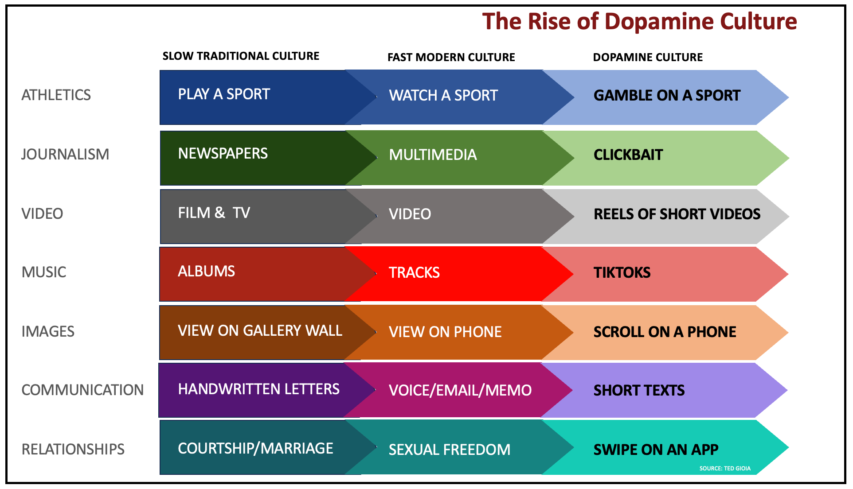

Of course there are no easy answers as to the explosion of this latest fad, but surely the proliferation of social media has something to do with it. Platforms such as TikTok are replete with activists explaining to teenagers that their feelings of confusion are probably evidence that they have been “born in the wrong body”. For pubescent girls who are uncomfortable with their physiological changes, as well as sudden unwanted male sexual attention, the prospect of identifying out of womanhood makes complete sense. These online pedlars have some snake-oil to sell. And while a limping epidemic in a medieval village would be unlikely to spread very far, social contagions cannot be so confined in the digital age.

Much of this is reminiscent of the recovered memory hysteria of the late twentieth-century, when therapist cranks promoted the idea that most victims of sexual abuse had repressed their traumatic memories from childhood. It led to numerous cases of people imagining that they had been abused by parents and other family members, and many lives were ruined as a result. One of the key texts in this movement was The Courage to Heal (1988) by Ellen Bass and Laura Davis, which made the astonishing and unevidenced claim that “if you are unable to remember any specific instances … but still have a feeling that something abusive happened to you, it probably did”.

A common feature of social contagions is that they depend upon the elevation of intuition over material reality. Just as innocent family members were accused of sexual abuse because of “feelings” teased out by unscrupulous therapists, many girls are now being urged by online influencers to trust the evidence of their emotions and accept a misalignment between their body and their gendered soul. We are not talking here about the handful of children who suffer from gender dysphoria, but rather healthy children who have been swept up in a temporary craze.