Actually, it’s dead easy. No math, no arithmetic. It is in fact the soul of common sense. But you have to understand that comparative advantage is the principle of cooperation, as against competition. The word “advantage” gets us thinking of competition, which is perfectly reasonable in our own individual lives — we do compete with other businesses or other writers or whomever. But the system as a whole, whatever it is, does well of course by cooperating, in business or science or family life. It’s not all we do, admittedly. We also compete. But within a household or a company or a world economy the job is to produce a result in the best way, cooperatively. If you are running a household or a sports team or a world economy, you would want to assign roles to the various contributors to the common purpose sensibly. It turns out to be precisely on grounds of comparative advantage.

Consider Mum and 12-year old Oliver, who are to spend Saturday morning tidying up the garage. Oliver is incompetent in everything compared with Mum. He cannot sweep the floor as quickly as she can, and he is truly hopeless in sorting through the masses of rubbish that garages grow spontaneously. Mum, that is, has an absolute advantage in every sub-task in tidying up the garage. Oliver is like Bangladesh, which is poor because it makes everything — knit goods and medical reactors — with more labor and capital than Britain does. Its output per person is 8.4 percent of what it is in Britain. So too Oliver.

What to do? Let Mum do everything? No, of course not. That would not produce the most tidied garage in a morning’s work. Oliver should obviously be assigned to the broom, in which his disadvantage compared with Mum is comparatively least — hence “comparative advantage.” An omniscient central planner of the garage-tidying would assign Mum and Oliver just that way. So would an omniscient central planner of world production and trade. In the event, there’s no need for an international planner. The market, if Trump does not wreck it, does the correct assignment of tasks worldwide. Bangladesh does not sit down and let Britain make everything merely because Britain is “competitive” absolutely in everything. And in fact Bangladesh’s real income has been rising smartly in recent years precisely because it has specialized in knit goods. It has closed its ears to the siren song of protecting its medical reactor industry. It gets the equipment for cancer treatment from Britain.

Comparative advantage means assigning resources of labor and capital to the right jobs, whatever the absolute productivity of the economy. It applies within a single family, or within a single company, or within Britain, or within the world economy, all of which are made better off by such obvious efficiencies. Following comparative advantage enriches us all, because it gets the job done best. Policies commonly alleged to achieve absolute advantage lead to protection — that is, extortion, crony capitalism, and the rest in aid of “competitiveness.”

Dierdre N. McCloskey, “A Punter’s Guide to a True but Non-Obvious Proposition in Economics”, 2017-10-16.

November 5, 2017

QotD: Explaining comparative advantage

September 19, 2017

The Merchant of Death – Basil Zaharoff I WHO DID WHAT IN WW1?

The Great War

Published on 18 Sep 2017For arms dealers like Basil Zaharoff, the late 19th and early 20th century was a time of never ending business opportunities, the great European powers modernised their armies drastically and conflicts like the Russo-Japanese War or the Balkan Wars meant that weapons of all kinds were always in demand. But no other man knew how to influence and profit from the warring nations like “The Merchant of Death” – Basil Zaharoff.

August 31, 2017

QotD: Standardized production versus customization

Standardization is the inevitable byproduct of industrialization. Yes, mass-market frocks do not fit as well as custom-made ones; yes, cabinets rolled out of factories by the thousands do not fit their owners as well as ones hand-made by your friendly local carpenter. That’s because the amount of additional labor required to customize handmade cabinets and sink installations to the height of the chef is trivial, and adds little to the cost of the job. On the other hand, stopping your assembly line and retooling to produce a different size adds quite a lot of cost. So does carrying multiple sizes of cabinets in inventory.

Arndt lightheartedly suggests going to customized kitchens, perhaps do-it-yourself ones. I suggest that Arndt price the tool kit that would be needed to make your own reasonably functional and attractive kitchen cabinets. Be sure to add in, too, the hours of labor that would be needed to do this, and the space you’d need in your home to build said cabinets. Go price custom cabinets, versus the one-size-fits-most available from Ikea or your local big box retailer. Compare these numbers. Suddenly you see why women happily embraced mass-produced kitchens that weren’t quite the ideal height.

Megan McArdle, “Kitchen Design Isn’t Sexist. It Liberated Women”, Bloomberg View, 2015-10-18.

August 4, 2017

Experimental Lightweight Browning High Power

Published on 3 May 2017

One of the handguns that resulted from the post-WW2 interest in standardizing arms among the future members of NATO was a lightweight version of the Canadian produced Browning High Power. Experiments began in 1947 to create first a lightened slide by milling out unnecessary material, and then additionally with the use of machined and cast aluminum alloy frames. The first major batch of guns consisted of six with milled alloy frames, with two each going to the Canadian, American, and British militaries for testing.

This would reveal that the guns were in general quite serviceable, except that the locking blocks tended to distort their mounting holes in the alloy frames under extended firing. The cast frames were generally unsuccessful, suffering from substantial durability problems. The program was cancelled in 1951 by the Canadian military, and the last United States interest was in 1952. The example in today’s video is one of the two milled frame guns sent to the US for testing.

July 27, 2017

Aluminium – The Material That Changed The World

Published on 24 Aug 2016

Thanks to the vlogbrothers for sponsoring this video. Have been following their work for years, it feels great to be supported by my role models!

Thank you to my patreon supporters: Adam Flohr, darth patron, Zoltan Gramantik, Josh Levent, Henning Basma.

Thanks to Dr. Barry O’Brien, from NUI Galway, for helping me with the final drafts of this script!

June 25, 2017

Spain and the Spanish Arms Industry in WW1 I THE GREAT WAR Special feat. C&Rsenal

Published on 24 Jun 2017

Spain was one of the neutral nations of World War 1. A deep social divide and a decline from world power meant that they stayed out of the global conflict. Still, the war affected Spain in many ways. One of the consequences was the establishment of a huge arms industry that supported France and other fighting nations.

Sometimes, the workman is right to blame his tools

Paul Sellers recently bought and tested a new Two Cherries brand “Gent’s saw” and was very unhappy with the tool:

This week I picked up a brand new gent’s saw straight from the pack made by the famous German tool makers Two Cherries. I noticed the unusual tooth shape, which strangely resembled the edge of a tin can when we used to open it with a multipurpose survival knife. I wondered how it would work and whether it was just a miscut. I examined several others and realised it was actually intentional as they were indeed manufactured that way. I offered the saw to the wood and the very middle cut with the dovetailed angle and the broken off section was the results of ten strokes.

“The long saw cut on the left is how the saw cuts by a man who has used such saws every day, six days a week for 53 years. The two to the right are how it cuts after sharpening and redefining the teeth.”

Could this truly be the end product of the once highly acclaimed Two Cherries of German tool manufacturing? I looked at the packet and, well, there it was; Made in Germany. So here is my perspective on the saw. Nice beechwood handle–nicely shaped (but it is unfinished), nice brass back, good quality steel plate, not too soft, not too hard. Two Cherries, the materials leave you no excuse for making such a poor grade product. YOU should be very ASHAMED of your product and yourselves. It is the very worst saw of any and all saws ever, ever, ever manufactured. I have never seen anything worse.

[…]

If you bought this saw and you thought the outcome was a result of your inexperience. It’s not. Blame the tool maker. It’s his pure arrogance to think he can pass something off to you like this and call it a dovetail saw. Shame on you Two Cherries, shame on you!

June 17, 2017

“Probably the best example of our carny-barker economy is Tesla”

The Z-Man on the post-modern business models used by Amazon, Facebook, and Tesla:

The key for Amazon making it all these years was to keep people focused on everything but their financials. This is not an exception. Faceberg will never have earnings to justify its share price. In fact, it will never have user rates to justify its ad revenue. It’s not unreasonable to think that everything about the business is fraudulent. That should trigger large scale audits and investigations into its business practices, but Facebook is on the side of angels in the cultural revolution, so its all good.

Probably the best example of our carny-barker economy is Tesla. To his credit, Musk has built a real factory that builds real cars. No one is going to say the Tesla is a work of art or even a practical car, but it is a car and the technology is impressive. The trouble is the company does not exist to make cars. It operates as a tax sink, where government subsidies flow into it and some portion of those subsidies turn into payments to the principles in the form of stock repurchases, debt service and compensation.

This only works if people think the venture will either one day turn a profit or the technology that it creates will result in something good down the road. To that end, Musk is regularly out doing his Lyle Lanley act, making all the beautiful people feel righteous by backing his ventures. He’s also telling Wall Street that he will soon be making and selling enough cars to turn a healthy profit, even without massive tax subsidies. The trouble is, that’s probably never happening, at least not with current management.

May 7, 2017

Canada-US trade relationship, visually

With all the talk (mostly from President Trump) about abandoning existing trade relationships like NAFTA, it’s worth looking at just how closely related the US and Canadian economies are (below the fold, because the graphic is yuuuuuge):

May 2, 2017

Tank Chats #8 Renault FT-17

Published on 4 Aug 2015

The eight in a series of short films about some of the vehicles in our collection presented by The Tank Museum’s historian David Fletcher MBE.

Conceived by General Jean-Baptiste Estienne and manufactured under the control of the Renault Company this was the world’s first mass-produced tank, 3800 being built in all.

They went into action for the first time on 31 May 1918 near Ploissy-Chazelle and proved very successful when they were used in numbers. British forces used a few Renaults as liaison vehicles while the United States Army used them in combat and copied the design.

April 20, 2017

STEEL MILL RAILROAD RELICS Still found in Pittsburgh, Pa

Published on 27 Nov 2016

Although it is 2016, and most mills closed in the 80’s, there are still many items still preserved in and around the Pittsburgh area. Here is just a small sampling.

April 6, 2017

Words & Numbers: Taxing Robots Does Not Compute

Published on 5 Apr 2017

This week, Antony and James break down Bill Gates’ recent suggestion that companies that use robots instead of human workers should pay employment taxes in order to fund new welfare programs.

March 11, 2017

QotD: US Army awards contract, losing bidder launches appeal (of course)

The Services should just acknowledge the reality of contracting anything in the seven-figure realm, and change initial award announcements to read: “The Initial Conditional Award of Contract XYZ is to Defense Conglomerate 1369. Work will commence after all Congressional Outraged Publicity-Seeking Posturing is exhausted and Butthurt Losing Contractor Challenges are adjudicated. We hope to run both those actions concurrently, and anticipate work will commence a minimum of 3-5 years behind schedule and costs grow at an exponential rate during this period, hence the budget supplemental is already in draft form for Newsies, Think Tanks, and Outraged Congresspersons to grind axes with.” Added caveat for this particular contract: “Additionally, a website has been established to collect all the comments from .40/.45 cal and steel-frame fanboyz to rant about How Stupid This Choice Is.”

John Donovan, posting to Facebook, 2017-02-28.

February 17, 2017

Industrial policy example – Kingston, Ontario

David Warren remembers when the government tampered with the free market to “save an industry” in Kingston:

Once upon a time, many years ago, I scrapped into one of these “no-brainer” political deals. The remains of the locomotive manufacturing business in Kingston, Ontario — whose century-old products I had glimpsed, still on the rails in India — were now on the block. A monster German corporation was offering to buy them, for the very purpose of competing, in Canada, with a (hugely subsidized, monopolist) Canadian corporation. The government stepped in, to “save” a Canadian industry, retroactively change the ground rules, and kick in more subsidies so that the Canadian monopolists, based in Montreal, could take over instead. This was accompanied by nationalist rhetoric, and Kingston was thrilled. Critics like me were unofficially deflected with bigoted anti-German blather held over from the last World War.

But I knew exactly what was going to happen. The local works, which would have been expanded by the foreign owner, were soon closed by the new Canadian owner, after studies had been commissioned to “prove” it was uneconomic. The latter’s last possible domestic competitor was thus snuffed out. The locals, whose lives had been for generations part of a proud Kingston enterprise, had been suckered. The politicians had told them it was little Canada versus big Germany. In reality, it was pretty little Kingston versus big ugly Montreal.

That is how the world works, with politics, so that whenever I hear of a big new national no-brainer scheme, my first thought is, which innocents are getting mooshed today?

January 25, 2017

Protectionism can save jobs … at the cost of even more jobs than it “saves”

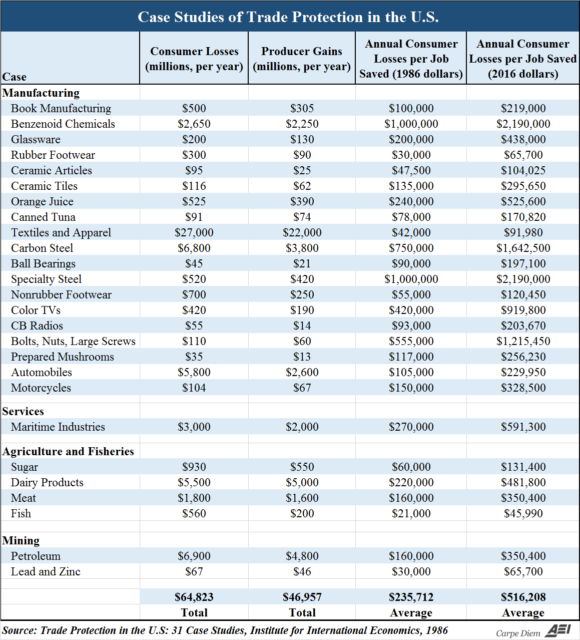

Mark Perry provides some context to the claim that protectionist policies can save American jobs:

According to Team Trump’s website, we’re told that “blue-collar towns and cities have watched their factories close and good-paying jobs move overseas, while Americans face a mounting trade deficit and a devastated manufacturing base. By fighting for fair but tough trade deals, we can bring jobs back to America’s shores, increase wages, and support U.S. manufacturing.”

Actually, it’s been capital investments in labor-saving technologies like robotics and increasing worker productivity that have led to the large majority of US factory job losses, not trade or outsourcing, as I documented recently here. And there’s been no devastation of America’s manufacturing base; to the contrary, real US manufacturing output has reached all-time high levels in recent quarters.

What’s Trump’s solution to the loss of US manufacturing jobs? America’s “first authentic protectionist to win the White House since the 1920s” has outlined a series of protectionist trade measures including tariffs (30-40-50%), “tougher trade deals” (likely trade deals to protect US manufacturers from foreign competition), “Buy American” policies, and border adjustment taxes, among other strategies to “save American jobs.”

Here’s a relevant question to ask: How have protectionist trade policies in the past worked out for the US economy and how expensive is it to save American jobs with the protectionist trade policies Trump is proposing? We can find some answers to those questions in a Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis research article published in 1988 by three economists “Protectionist Trade Policies: A Survey of Theory, Evidence and Rationale,” which presented a summary of the empirical evidence on trade protectionism from the 1986 book published by the Institute for International Economics Trade Protection in the United States: 31 Case Studies. Even though the research and empirical results are from the 1980s, this article and book provide useful empirical evidence on the costs of protectionism to bring some much-needed sanity to the debate on trade policy to counterbalance the favorable treatment being given to protectionism these days.