On the consolidation of power within the administrative bureaucracy:

The character of the college as a micro-community of academics is being doubly subverted: from within, by the rapid growth of bureaucratic roles taken up by professional administrators, and from without, by a university seeking to centralise control and elide differences among the colleges. The more uniform the overall environment becomes, the more rapidly it will suffer from the bad decisions inevitably yet to be made.

On the metastasis of overpaid, officious administrators:

“The content of this letter is extremely important, so please read it carefully.” It isn’t often that the university speaks to its employees in this way. This was a follow-up email from the former pro-vice-chancellor for strategy and planning, David Cardwell. He wanted academics to complete his Time Allocation Survey by tabulating how many hours were spent across a vast suite of possible activities. It is characteristic of contemporary Cambridge that the strongest rhetoric it can muster is directed toward this self-serving bureaucratic exercise. Cardwell rubbed shoulders with four other pro-vice-chancellors, all enjoying a salary that is several multiples of the typical university academic, and surpasses the Prime Minister’s.

This administrative overgrowth is, by the way, a historical novelty:

All of this is new: until 1992, the role of vice-chancellor was covered in short stints by the Heads of House, who paused their college governance while the rest of Cambridge got on with what they were here to do. Now we have not only career administrators at the helm, but their five deputies, for an annual cost of around £1.5 million. All the while, the university fails to find the money to keep important subjects alive, such as the centuries-old study of millennia-old Sanskrit.

I’ve been pointing this out for years. Until very recently, administrative functions in universities were largely filled by senior academics: you got bullied into shouldering the unwelcome burden because somebody had to do it, and you drew the short straw. There is nothing that a serious person despises more than paperwork, especially a scholar, who would much rather be happily buried in whatever esoterica he has made his field of study. Forcing academics into administrative roles ensured that the people filling those offices were incentivized to keep the paperwork to an absolute minimum; the last thing they wanted was to create more of the hateful stuff.

Enter, some decades ago, the professional administrators. Initially, these usually had some sort of academic qualification, and still largely do – albeit typically in fake non-disciplines, “public administration” or what have you – but they were not in any sense scholars. They were managers. Give us your burden, they said; we’ll do all the annoying paperwork for you, and you can concentrate on your very important research, you very important scholars, you. Thus the professoriate, like gullible fools, handed over the keys to the kingdom.

Unlike professors, managers are incentivized to create as much administrative complexity as they can: the more administration there is to perform, the more administrators the institution needs, and the larger the fiefdoms senior administrators can command. Since admin typically has control of the budget, they were easily able to appropriate the necessary funds. The result has been the explosive proliferation of useless eaters with lavish salaries and ridiculous titles like Senior Vice Assistant Dean for Excellence or Junior Associate Student Life Provost. At many universities, administrators now exist in a 1:1 ratio with the student body.

Admin have sucked shrinking university budgets dry, with real intellectual consequences: they aren’t going to fire themselves, and they sure aren’t taking a salary cut, so to make up budget shortfalls academic programs with low enrolment get the axe. Butterfield’s reference to the closure of the Sanskrit program is an example of this; there are many such examples, and they are increasingly common. To brains built out of buzzwords and spreadsheets, everything is either a marketing technique or a revenue stream, and if a program isn’t popular enough to subsidize their summer vacations in Provence or social-justicey enough for them to brag to their beach friends about how progressive they are, it serves no purpose.

This ability of university administrations to close down programs illustrates something else, which is that they are the real power on campus. The academics are mere employees: they will teach whichever students the admin decides to admit, will teach those students whatever the admin says to teach them, will not teach what the admin tell them not to teach, will teach in whatever manner admin decides is best, and will evaluate the results of that instruction in whatever fashion admin mandates they be evaluated.

As members of the managerial class, university administrators are drones of the global managerial hive mind, and instinctively exert a homogenizing influence. Old, parochial practices must be jettisoned in favour of standardizing the institutions they manage.

As for our age-old titles – of lecturer, senior lecturer, reader and professor – these were replaced with American titles so as to be “more intelligible” to a global audience. … To conjure up a world of “assistant professors” and “associate professors”, who in fact have no supporting relationship to “the professors”, makes a mockery of that venerable system.

Administrators dislike horizontal social relationships amongst faculty. Peer-to-peer network architectures are hard to control; they prefer a server-terminal model, with management as the server through which all communications pass, and professors as the terminals, who can be regulated through systems of permissions. Thus, they set about dissolving those institutions that facilitate conviviality amongst the faculty:

It was telling that a few years ago the authorities silently closed down the University Combination Room, the 14th-century hall in which academics could freely convene outside their individual colleges.

Administration is also sneaky, adopting governance practices that minimize whatever legacy powers the professoriate still possesses:

Although in theory Cambridge academics are self-governing, the move to online voting, with minimal announcement, allows for many university policies to be driven through by those who want them enacted.

Butterfield understands full well that the problems are hardly unique to Cambridge:

All this I say of Cambridge. But these issues go right across the university sector … The public need to trust and respect the elite academic institutions they fund; but that respect is waning, as stories continue to reveal politicised teaching, grade inflation, authoritarian campus policies and lurid, even laughable, research grants. The ambitions of our whole education system are ultimately pegged to the achievements at the very pinnacle of academia. If Cambridge can’t resist decline, who can?

The obvious answer is: no one can resist this. Not Cambridge, not Oxford, not University College London, not Harvard, not Princeton, not MIT, and not Whittier College. The problem is too systemic; the rot too deep. Decades of administrative consolidation of power has subsumed the ivory tower into an appendage of the global asset management system. Generations of ideological infection by the mind virus of cultural Marxism, wokeism, critical social justice, gay race communism, whatever you want to call it, has poisoned the minds of too many of the faculty. Generations of steadily declining standards, an inevitable consequence of massively increased enrolment which of unavoidable necessity heavily sampled the fat middle of the IQ distribution, has thinned out the influence of the bell curve’s rarefied tail to statistical irrelevance. After all of this, the only way to save the university is to purge it, of the great mass of low-performing affirmative action students, of the diversity hire academics who substitute clumsy sermonizing for the scholarship they can neither understand nor perform, and most especially of the great tumorous mass of useless administrators.

Such a purge, to be effective, would need to be thorough. To be thorough, it would remove almost everyone in the system. This would be the same as destroying the system. To save the patient, one would have to kill the patient.

Therefore no such purge will take place.

Instead, the system will crumble, buckle under its own weight, and eventually collapse.

As, in fact, it is doing.

John Carter, “Crumbling DIEvory Towers”, Postcards From Barsoom, 2024-10-25.

January 27, 2025

QotD: The bureaucratization of university administration

December 30, 2024

Ted Gioia on 2025’s most likely trends

Peeking out from behind the paywall, the latest installment of Ted Gioia‘s arts & culture briefing includes some good news for those of us who still remember when book stores actually sold books (unlike the last time I visited an Indigo store to find that the books were even more of an afterthought than ever):

“Barnes & Noble Book Store” by JeepersMedia is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

The Barnes & Noble turnaround is really happening — and everybody in the culture business should learn from it.

More than a year ago, I celebrated the arrival of a new boss at Barnes & Noble who actually loves books.

This led him to do all sorts of brave things. He stopped promoting new titles based on kickbacks from publishers, and instead showcased books that people might actually enjoy reading.

This was an example of stealth culture mentioned above. Shoppers had no idea that the promoted books at the front of the store were chosen on the basis of financial incentives, not quality. And new boss Jamie Daunt shook the entire publishing business by turning down the cash.

He also empowered employees in the store, giving them freedom to feature books that they loved. He told his local booksellers to remove every title from every shelf, and “weed out the rubbish”. He wanted the staff to be excited about the books they sold.

I now have a happy update to my previous report.

Barnes & Noble has more than 60 new locations opening this year, and store foot traffic is improving steadily.

In an especially inspiring move, the company recently reopened a huge retail space in DC it had abandoned in 2013. After more than a decade, it returned to the same location and opened a flagship store.

When he took over, Daunt saw that the stores were “crucifyingly boring”. But now the excitement is back. Some visitors even compare Barnes & Noble nowadays to a theme park for books.

Kendra Keeter-Gray, a BookTok content creator with over 100,000 followers, told CNN that she and her friends could spend anywhere between 30 minutes to a few hours inside a Barnes & Noble, usually in the BookTok section where they trade recommendations and flip through currently trending novels.

“When you go to Barnes, it’s like an excursion almost. I would equate it to when I was little and my parents would take me to Six Flags,” she said.

Meanwhile here’s a completely different strategy for the book business …

In Japan, writers can rent out their own shelf at a local bookstore.

The new trend in Japanese bookstores is to sublease the shelves to outsiders. The result is the exact opposite of algorithm-chosen books. Every shelf is filled with surprises.

According to the South China Morning Post:

“Here, you find books which make you wonder who on earth would buy them,” laughs Shogo Imamura, 40, who opened one such store in Tokyo’s bookstore district of Kanda Jimbocho in April.

“Regular bookstores sell books that are popular based on sales statistics while excluding books that don’t sell well,” says Imamura … “We ignore such principles”.

December 20, 2024

QotD: A’s hire A’s and B’s hire C’s

so how does even a little DEI lead to full incompetence contagion? i would like to posit a very simple emergent algorithm rooted in a simple and longstanding organizational idea:

A’s hire A’s and B’s hire C’s. (and you seriously do not want to meet the people C’s hire)

that’s it. that’s all we need to extrapolate and plot it.

this pattern emerges in response to two simple drives affecting all those who lack ability to compete […]

the essence of this is simple: the highly competent (A’s) wish to be surrounded by other highly competent people. an organization of mostly A’s (or at least A’s in management) thrives and gets lots done. it innovates. it rewards achievement and ability. it’s a meritocracy. because that’s what A’s want.

and B’s hate this. they cannot get ahead and they live in fear of A’s beneath them coming for their jobs and hatred of A’s above them who prevent advancement and who make demands for performance.

they do not want their jobs taken, so they respond to this by hiring only those less competent than themselves to work under them (C’s). this is how they hold position and avoid challenge and threat.

ideally, they’d also like to clear any A’s above them out of the way so they can generate some upward mobility. they cannot do this on a meritocratic axis, so they seek another one to supplant it.

they seek to move hiring and promotion to some other quality than ability then reinforce it with doctrine.

the pretext itself is incidental to this process. it does not really matter what it is.

it just has to be “something other than competence” and you land in this self-referential recursive trap.

el gato malo, “the mediocrity downspiral”, bad cattitude, 2024-09-10.

December 10, 2024

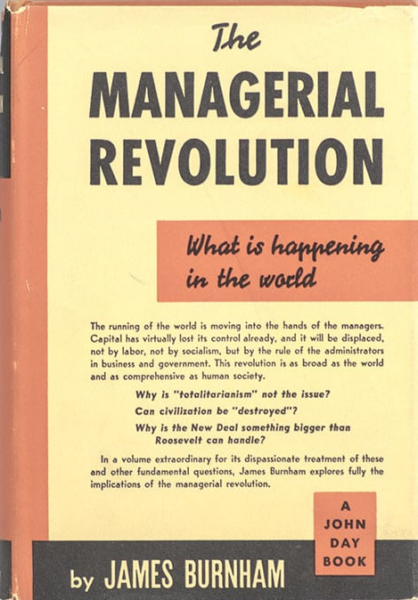

Countering the “Managerial Revolution”

Tim Worstall discusses the rise of the managerial class — described in 1941’s Managerial Revolution by James Burnham — and how detrimental to individual enterprises and the wider economy managerialism has been:

This, rather joyously, explains a lot about the modern world. We could go back to the mid-1980s and the bloke who ran the ‘baccy company written up in Barbarians at the Gates. In which he, as CEO, had a fleet of private planes, the company paid for his 11 country club memberships and so on. His salary was decent, sure, but the corporation rented him all the trappings of a Gatsbyesque — and successful — capitalist. Until the actual capitalists — the barbarians — turned up at those gates and started demanding shareholder returns.

Or we can think of the bureaucratic classes in the UK in more recent decades. Moving effortlessly between this NGO, that quasi-governmental body and a little light sitting on the right government inquiry. All at £1500 a day and a damn good pension to follow.

Or, you know, adapt the base idea to taste. There really is a bureaucratic and managerial class that gains the incomes and power of the capitalists of the past without having to do anything quite so grubby as either risk their own money or, actually, do anything. They, umm, administer, and the entire class is wholly and absolutely convinced that everything must be administered and they’re the right people to be doing that.

You know, basically David Cameron. Met him once, when he was just down from uni. At a political meeting – drinkies for the Tory activists in a particular council ward, possibly a little wider than that. Hated him on sight which I agree has saved me much time over the decades. And I was right too. There is nothing to Cameroonism other than that the right sort of people should be administering — the managerial revolution.

Sure, sure, we used to have the aristocracy which assumed the same thing but we did used to insist that they could chop someone’s head off first — show they had the capability. Also, they didn’t complain nor demand a pension when we did that to them if they lost office.

But the bit that really strikes me. France — and thereby the European Union — seems to me to be where this Managerial Revolution has gone furthest. Get through the right training (the “enarques“) and you’re the right guy to be a Minister, run a political party, manage the oil company, sort out the railways etc. You don’t have to succeed or fail at any of them, you’re one of the gilded class that runs the place. Because, you know, everything needs to be run and one of this class should do so.

The divergence or even active conflict of interests between the owners and the non-owning managers is part of the larger Principal-Agent Problem.

September 18, 2024

September 15, 2024

August 23, 2024

June 20, 2024

The “Idiot Nephew Theory” of show business management

Ted Gioia recalls his hopes of getting into the entertainment industry after graduation:

The story of how I became a strategy consultant is shameful.

I was a student at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business, and needed a job after graduation. I wanted to work in the music or entertainment industries — but I soon learned this was an impossible dream.

They didn’t want me. And they didn’t want my classmates either.

Hundreds of companies came to our business school to recruit talent, and they included most of the leading US corporations. So I talked with everybody — Coca Cola, Morgan Stanley, Atari, Procter & Gamble, you name it.

But no record label or movie studio ever showed up. They didn’t even send job listings.

Can you guess why?

I asked around on campus and was told the following (off the record):

Come on, Ted. You will never see the entertainment business recruit here. Those folks are not looking for business talent.

They give the choice jobs to their family members — the idiot nephew gets hired, not an MBA. Even better if it’s an idiot son.

And if there are other openings? Well … You’ve heard about the casting couch, haven’t you? Let me give you a hint — that couch isn’t just for auditioning the cast.

But you wouldn’t want a job there even if they gave you one. When time comes for a promotion, the drooling idiot nephew moves up — not you.

I’ve never shared that story before — because I know how people inside the music business hate hearing it.

And maybe it’s not a fair story.

All I can say is that I found this advice very helpful. I stopped planning on a career in the music business. And I also developed a very useful theory to explain why record labels are so bad at making strategic decisions.

I call it the “Idiot Nephew Theory”:

THE IDIOT NEPHEW THEORY: Whenever a record label makes a strategic decision, it picks the option that the boss’s idiot nephew thinks is best.

And what does the idiot nephew decide? That’s easy — they always do whatever the company lawyer recommends.

Maybe this theory is wrong. All I can say is that it helps me predict events in the entertainment industry with a surprising degree of accuracy.

I always operate on the assumption that there’s no business strategy in the music or movie business — only legal maneuvering.

Years later, when the music business got totally reamed by tech companies — a phase we’re still living through, by the way — I wasn’t surprised in the least. The record labels respond to every new music technology by litigating, but whenever they encounter a company with more legal clout than them (Apple or Google/YouTube, for example), they simply gave up.

In the future, you can test this theory yourself. You will see that it possesses great explanatory power.

May 22, 2024

The new queen of the AWFLs

Elizabeth Nickson on the rise of new NPR CEO, Katherine Maher:

Banner for Christopher Rufo’s article on Katherine Maher at City Journal.

https://christopherrufo.com/p/katherine-mahers-color-revolution

The polite world was fascinated last month when long-time NPR editor Uri Berliner confessed to the Stalinist suicide pact the public broadcaster, like all public broadcasters, seems to be on. Formerly it was a place of differing views, he claimed, but now it has sold as truth some genuine falsehoods like, for instance, the Russia hoax, after which it covered up the Hunter Biden laptop. And let’s not forget our censor-like behaviour regarding Covid and the vaccine. NPR bleated that they were still diverse in political opinion, but researchers found that all 87 reporters at NPR were Democrats. Berliner was immediately put on leave and a few days later resigned, no doubt under pressure.

Even more interesting was the reveal of the genesis of NPR’s new CEO, Katherine Maher, a 41-year-old with a distinctly odd CV. Maher had put in stints at a CIA cutout, the National Democratic Institute, and trotted onto the World Bank, UNICEF, the Council on Foreign Relations, the Center for Technology and Democracy, the Digital Public Library of America, and finally the famous disinfo site Wikipedia. That same week, Tunisia accused her of working for the CIA during the so-called Arab Spring. And, of course, she is a WEF young global leader.

She was marched out for a talk at the Carnegie Endowment where she was prayerfully interviewed and spouted mediatized language so anodyne, so meaningless, yet so filled with nods to her base the AWFULS (affluent white female urban liberals) one was amazed that she was able to get away with it. There was no acknowledgement that the criticism by this award-winning reporter/editor/producer, who had spent his life at NPR had any merit whatsoever, and in fact that he was wrong on every count. That this was a flagrant lie didn’t even ruffle her artfully disarranged short blonde hair.

Christopher Rufo did an intensive investigation of her career in City Journal. It is an instructive read and illustrative of a lot of peculiar yet stellar careers of American women. Working for Big Daddy is apparently something these ghastly creatures value. I strongly suggest reading Rufo’s piece linked here. It’s a riot of spooky confluences.

Intelligence has been embedded in media forever and a day. During my time at Time Magazine in London, the bureau chief, deputy bureau chief and no doubt the “war and diplomacy” correspondent all filed to Langley and each of them cruised social London ceaselessly for information. Tucker Carlson asserted on his interview with Aaron Rogers this week that intelligence operatives were laced through DC media and in fact, Mr. Watergate, Bob Woodward himself, had been naval intelligence a scant year before he cropped up at the Washington Post as “an intrepid fighter for the truth and freedom no matter where it led”. Watergate, of course, was yet another operation to bring down another inconvenient President; at this juncture, unless you are being puppeted by the CIA, you don’t get to stay in power. Refuse and bang bang or end up in court on insultingly stupid charges. As Carlson pointed out, all congressmen and senators are terrified by the security state, even and especially the ones on the intelligence committee who are supposed to be controlling them. They can install child porn on your laptop and you don’t even know it’s there until you are raided, said Carlson. The security state is that unethical, that power mad.

Now, it’s global. And feminine. Where is Norman Mailer when you need him?

April 4, 2024

Boeing and the ongoing competency crisis

Niccolo Soldo on the pitiful state of Boeing within the larger social issues of collapsing social trust and blatantly declining competence in almost everything:

“Boeing 521 427”by pmbell64 is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

By now, most of you have heard of the increasingly popular concept known as “the competency crisis”. For those of you who haven’t, the competency crisis argues that the USA is headed towards a crisis in which critical infrastructure and important manufacturing will suffer a catastrophic decline in competency due to the fact that the people (almost all males) who know how to build/run these things are retiring, and there is no one available to fill these roles once they’re gone. The competency crisis is one of the major points brought up by people when they point out that America is in a state of decline.

As all of you are already aware, there is also a general collapse in trust in governing institutions in the USA (and all across the West). Cynicism is the order of the day, with people naturally assuming that they are being lied to constantly by the ruling elites, whether in media, government, the corporate world, and so on. A competency crisis paired with a collapse in trust in key institutions is a vicious one-two punch for any country to absorb. Nowhere is this one-two combo more evident than in one of America’s crown jewels: Boeing.

I’m certain that all of you are familiar with the “suicide” of John Barnett that happened almost a month ago. John Barnett was a Quality Control Manager working for Boeing in the Charleston, South Carolina operation. He was a “lifer”, in that he spent his entire career at Boeing. He was also a whistleblower. His “suicide” via a gunshot wound to the right temple happened on what was scheduled to be the third and last day of his deposition in his case against his former employer.

In more innocent and less cynical times, the suggestion that he was murdered would have had currency only in conspiratorial circles, serving as fodder for programs like the Art Bell Show. But we are in a different world now, and to suggest that Barnett might have been killed for turning whistleblower earns one replies like “could be”, “I’m pretty sure that’s the case”, and the most common one of all: “I wouldn’t doubt it”. No one believes that Jeffrey Epstein killed himself. Many people believe the same about John Barnett. The collapse in trust in ruling institutions has resulted in an environment where conspiratorial thinking naturally flourishes. Maureen Tkacik reports on Boeing’s downward turn, using Barnett’s case as a centre piece:

“John is very knowledgeable almost to a fault, as it gets in the way at times when issues arise,” the boss wrote in one of his withering performance reviews, downgrading Barnett’s rating from a 40 all the way to a 15 in an assessment that cast the 26-year quality manager, who was known as “Swampy” for his easy Louisiana drawl, as an anal-retentive prick whose pedantry was antagonizing his colleagues. The truth, by contrast, was self-evident to anyone who spent five minutes in his presence: John Barnett, who raced cars in his spare time and seemed “high on life” according to one former colleague, was a “great, fun boss that loved Boeing and was willing to share his knowledge with everyone,” as one of his former quality technicians would later recall.

Please keep in mind that this report offers up only one side of the story.

A decaying institution:

But Swampy was mired in an institution that was in a perpetual state of unlearning all the lessons it had absorbed over a 90-year ascent to the pinnacle of global manufacturing. Like most neoliberal institutions, Boeing had come under the spell of a seductive new theory of “knowledge” that essentially reduced the whole concept to a combination of intellectual property, trade secrets, and data, discarding “thought” and “understanding” and “complex reasoning” possessed by a skilled and experienced workforce as essentially not worth the increased health care costs. CEO Jim McNerney, who joined Boeing in 2005, had last helmed 3M, where management as he saw it had “overvalued experience and undervalued leadership” before he purged the veterans into early retirement.

“Prince Jim” — as some long-timers used to call him — repeatedly invoked a slur for longtime engineers and skilled machinists in the obligatory vanity “leadership” book he co-wrote. Those who cared too much about the integrity of the planes and not enough about the stock price were “phenomenally talented assholes”, and he encouraged his deputies to ostracize them into leaving the company. He initially refused to let nearly any of these talented assholes work on the 787 Dreamliner, instead outsourcing the vast majority of the development and engineering design of the brand-new, revolutionary wide-body jet to suppliers, many of which lacked engineering departments. The plan would save money while busting unions, a win-win, he promised investors. Instead, McNerney’s plan burned some $50 billion in excess of its budget and went three and a half years behind schedule.

There is a new trend that blames many fumbles on DEI. Boeing is not one of those. Instead, the short-term profit maximization mindset that drives stock prices upward is the main reason for the decline in this corporate behemoth.

March 15, 2024

Peter Turchin’s notion of the “overproduction of elites”

Severian is on a mini-vacation at the moment, but still managed to find time to share some thoughts about Turchin’s “overproduction of elites”:

University graduation – a large crowd of students at a graduation ceremony in Ottawa, Ontario. This was the thumbnail image used on the “Elite overproduction” Wikimedia page, which seemed quite appropriate.

Photo by Faustin Tuyambaze via Wikimedia Commons.

Let us consider “the overproduction of elites”. Those who love Peter Turchin’s work love this phrase, as it finally gives a name to a phenomenon we’ve all noticed: The creation, promotion, and indeed valorization of what would more properly be called social barnacles — they don’t move, can’t change, and eventually bring whatever they infest to a complete halt. Those who dislike his work often haven’t read it, so they object to the use of the word “elite” — again, these are social barnacles; what’s elite about them?

Which is precisely Turchin’s point — “elite” is a descriptor of their lifestyle, and most importantly their self-image; it is almost perfectly opposed to their actual utility. The modern Ed Biz is set up to do little else but produce these (pseudo) elites, and therefore a kind of Say’s Law takes hold. Say’s Law, you’ll recall, is vulgarly summarized as “Supply creates its own demand,” and that’s what we see with the (pseudo) elites churned out by every college in the land — they expect, indeed they demand, “jobs” commensurate with their “education”, and thus make-work “jobs” in the Apparat are brought into being.

They take out massive student loans to get the “jobs”; they “work” the “jobs” to service the debt, and so on.

But that’s true of most “white-collar” “jobs” these days. What separates the “elites”, in Turchin’s usage, from the rest of them is not their utility, or lack thereof — the economy, such as it is, would function just as well (or not) with far fewer lawyers, accountants, insurance adjusters, and so on. The difference, comrades, is what we must call Revolutionary Class Consciousness,

stealingnationalizingsocializingliberating a phrase from Lenin.An accountant, I’d wager, views his work as a technical specialty. They’re “rude mechanicals” (that’s Shakespeare, darlin’; evidently Mr. Ringo is an educated man). Maybe not so “rude” — accountants make good scratch; they’re middle to upper-middle class, economically — but basically technicians. Accounting is a highly-trained, well-compensated job, but that’s all it is: A job. Accounting is what an accountant does; it’s not what an accountant IS. Contrast that to the overproduced “elites”, in Turchin’s sense, and you see what Turchin’s sense really means: An “elite” really IS his job title.

Note the shift: His job title. As we all know, so many of the overproduced “elite” do no meaningful work. How could they? We could easily do this for most any “job” in the Apparat, but one example will suffice. Consider “Journalist”. Formerly called “Reporter”, and back then it required some actual productive output. Some “shoe leather”, as the phrase was. To find out what they were up to at City Hall, you actually had to physically go down to City Hall and follow the Mayor around. These days — the days when Reporters are now Journalists — it’s just stenography. And not even real stenography, Claudine Gay-style stenography — the Mayor’s press secretary (who probably went to college with you) emails you a press release; you change a word or two and then reprint it, basically verbatim, under your byline.

A monkey could be trained to do it. Hell, a chatbot could be trained to do it, and that’s probably a good quick-and-dirty definition of a Turchin-style overproduced “elite”: If whatever “work” he does could easily be replaced by a chatbot, with no appreciable drop-off in either productivity or quality. Because that’s the key to understanding these people: They know damn good and well, at some almost-but-not-quite conscious level, that they’re social barnacles. That is the “base” upon which the “superstructure” — again stealing terms from Onkel Karl — of their Revolutionary Class Consciousness is built.

February 18, 2024

Indigo’s very bad third quarter may not be all bad news

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte discusses Indigo’s latest earnings report and points out a few things that may indicate better things to come if the firm continues its “refocus” on bookselling as its primary line of business:

“Indigo Books and Music” by Open Grid Scheduler / Grid Engine is licensed under CC0 1.0

Indigo Books & Music last week reported its third quarter financial results, covering the months of October to December 2023. Because retailers make most of their money in advance of the holiday season, Indigo’s third quarter is its most important quarter — the one that makes or breaks the year. It wasn’t good.

Revenue for the three-month period was $371 million compared to $423 million in the same period last year. Net income for the quarter was $10 million compared to $34.3 million in the prior year. Given that the company had already lost more than $40 million in the first two quarters of the year and that its fourth quarter is traditionally soft, Indigo is looking at another annus horribilis come its March 31 year end.

After every quarter, Indigo’s CEO and CFO discuss the company’s results and take questions from shareholders on a conference call. I tuned in to this quarter’s call to hear company founder Heather Reisman, recently returned as CEO, admit that it was a “challenging” time for the business. She attributed the poor performance to the ongoing repercussions of last winter’s ransomware attack, overbuys of the wrong kind of general merchandise (non-book items such as dildos, blankets, and cheeseboards), and “the premature launch of our new e-commerce platform”.

Amid all the ugly results, I heard a few things that might strike anyone interested in the Canadian book publishing industry as positive.

You’ll remember that Heather spent a few months in the doghouse last summer after announcing a terrible fiscal 2023. She retired and then un-retired in September and, on her return, pledged to take SHuSH‘s advice, clear her shelves of the dildos and cheeseboards that represent half of Indigo’s business, and recommit to selling books. I wasn’t sure if she meant it or just wanted the business community to know she was up on SHuSH. Apparently she meant it.

On the call, she spoke at length of her “transformation plan” to “connect meaningfully with book lovers”. She apparently spent the autumn shrinking her general merchandise inventory — much of the poor financial performance was due to unloading it at steep discounts. In fact, if you back out the aggressive discounting of unwanted crap, Indigo’s recent holiday season hit a slightly higher level of profitability than the prior year. Heather meanwhile reinvested in book inventory, “consistent with our long-term brand mission to inspire reading”.

I was heartened by this, more so when it emerged on the call that there are sound business reasons for recommitting to books. The printed word turned out to be Indigo’s most resilient retail channel last year. It was down only 8 percent. General merchandise was down 18.5 percent. Heather thinks general merchandise was hit especially hard because the guy she’d hired to run the place in her absence didn’t have the right assortment in stores at Christmas. That may be true, but 18.5 percent is still a big drop.

The 8 percent decline in books looks okay in relation to the rest of Canada’s retail economy. Canadian Tire just announced its results from the last quarter of 2023 and revenue was down 17 percent across the board. That suggests books more than held their own in a weak environment.

It seems reasonable to expect that if Indigo follows through on Heather’s promise and refocuses its brand and its marketing efforts and its in-store experience on books and reading, the business has a future. It will take time, as she repeatedly reminded listeners on the call. There’s still a canopy bed in the middle of the company’s flagship bookstore in Ottawa.

February 9, 2024

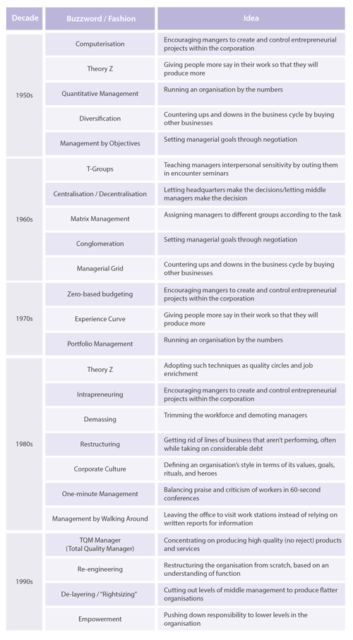

You can’t pro-actively synergize action-oriented metrics in the heat of battle

No, I’m not sure if that headline makes any sense, as I was never particularly receptive to the latest buzzwords of any given management fad that went through from the 70s onwards. They all seemed to share a few characteristics along with a bespoke sheaf of buzzwords, PowerPoint slides galore, and lots of spendy courses you had to send all your employees to endure. Is there anything more dispiriting to staff morale than a VP or director who’s just returned from a week-long training seminar in an exotic location on this year’s latest “revolutionary” “transformational” management fad?

It’s bad when companies that make widgets or smartphone apps or personal hygiene products fall for these scams, but it’s terrifying to discover that your military isn’t immune … and in fact revel in it:

Image from “Fads and Fashions in Management”, The European Business Review, 2015-07-20.

https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/fads-and-fashions-in-management/

We spent these last few decades since the fall of the Soviet Union weaving a comfortable web of CONOPS and implemented “efficiencies” constructed of consultant-speak, weekend-MBA jargon, and green eyeshade easy-buttons bluffed from the podium by The Smartest People in the Room™ to an audience on balance populated by people who already had the short list of jobs they wanted once they shrugged off their uniform in a PCS cycle or two.

Agree, endorse, parrot, prepare …. profit!

War is New™!, Revolutionary™!, Transformational™!. Hard power is Offset™! If we change a bunch of simple words in to multi-syllabic cute acronyms … then the future will be ours, our budgets will be manageable, and our board seats will be secured! Efficiency to eleventy!

Facing the People’s Republic of China on the other side of the International Date Line … how efficient do you feel? How effective?

Something very predictable happened in our quarter century roadtrip on the way to Tomorrowland; we realized instead we wound up on Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride instead.

I would like the record to show here in 2QFY24 that this exact problem was discussed in detail back when I was a JO in the mid-1990. This is not shocking to anyone who is wearing the uniform of a GOFO. They lived the same history I did.

We knew we were living a lie that we could sustain a big fight at sea. An entire generation of Flag Officers led this lie in the open and ordered everyone else to smile through it. Ignore your professional instincts, and trust The Smartest People in the Room™.

Once again, Megan Eckstein brings it home;

If U.S. military planners’ worst-case scenario arose in the Pacific — having to defend Taiwan from a Chinese invasion — American military forces would target Chinese amphibious ships.

Without them, according to Mark Cancian, who ran a 2022 wargame for the Center for Strategic and International Studies that examined this exact scenario, China couldn’t invade the neighboring island.

…

U.S. submarines would “rapidly fire everything they have” at the multitude of targets, Cancian said, “using up torpedoes at a much, much higher rate than the U.S. has expected to do in the past.”

Navy jets, too, would join in — but they’d run out of Long Range Anti-Ship Missiles within days, …

It’s this nightmare scenario that’s driving the Navy to increase its stockpile of key munitions: the LRASM, the MK 48 heavyweight torpedo, the Standard Missile weapons and the Maritime Strike Tomahawk, among others.

Over a decade after the Pacific Pivot, a couple of years after the US Navy became the world’s second largest navy after being the worlds largest for living memory of 99% of Americans, and two years after the Russo-Ukrainian War reminded everyone that, yeah … 3-days wars usually aren’t.

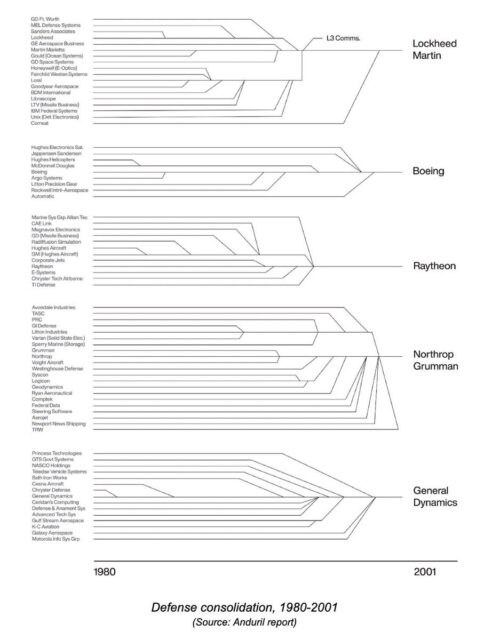

And the defence industries of the 1980s and 90s have all swallowed up smaller competitors — again following “normal” business practices of the time, seeking economies of scale and manufacturing efficiencies and closing down less-profitable assembly lines or entire lines of business.

Let’s go back to SECDEF Perry’s 1990s “Last Supper”, you know, the one that was all about the efficiencies of consolidation of the defense industry.

Three decades later, what is the solution to the strategic risk we find ourselves in due to our inability to arm ourselves?

… “the bottleneck is rocket motors” because so few companies are qualified to build them for the United States, Okano explained. To help, the Navy issued a handful of other transaction agreement contracts to small companies who will learn to build the Mk 72 booster and the Mk 104 dual-thrust rocket motor so prime contractors have more qualified vendors to work with, she added.

LOLOLOL … what “small companies?” That ecosystem is “old think”. If we need to go back to that structure, that will take decades not just to build, but decades of a viable demand signal.

Looks like we have started that as “small companies” perhaps repurpose part of their company to a military division. If we can just stop them from being gobbled up by the primes, it might be nice to return to a more robust, competitive ecosystem. Soviet-like consolidation and McNamaraesque efficiencies got us here, perhaps time to try something old as new again.

Nothing is less efficient to go to war with than a military designed for an efficient peace.

October 21, 2023

“… we’re not a business publication. One of them can point out that corporate governance is a joke in Canada”

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte reviews a recent BNN Bloomberg interview with Heather Reisman former-and-now-current-again CEO of Canada’s only big box book retailer, Indigo:

“Indigo Books and Music” by Open Grid Scheduler / Grid Engine is licensed under CC0 1.0

Heather Reisman gave an interview to Amanda Lang of BNN Bloomberg last week, her first effort to explain a summer of screwball management at Canada’s only bricks-and-mortar book chain.

[…]

How did Heather explain the zany sequence of events that started with her reporting Indigo’s fourth massive annual loss in five years in May; saw her booted in June from her role as executive chairman of Indigo, the company she founded, by her husband and controlling shareholder, Gerry Schwartz, along with every member of the board of directors who wasn’t personally beholden to Gerry; saw her spin her exit as a personal life-stages choice (“deciding when it is time to move on is one of the toughest decisions a founder must make”); saw her hand-picked successor and CEO, long-time British clothing retailer Peter Ruis, grab a seven-figure payout and make his own exit in September; saw the company announce that it would “act swiftly to find the right leader to move the company forward following Peter’s resignation”; saw Heather reinstated at the head of the chain two weeks later?

She didn’t. How could anyone explain that?

Heather bullshitted her way through the interview. It was all Ruis’s fault, she told Amanda. Indigo “took a journey off brand” under Ruis. She’d put him in charge of a book chain and “suddenly I was hearing that we were getting famous for selling $550 barbecues,” she said. “Somehow vibrators turned up in our stores and I remember saying ‘no, that’s not who we are.'” Ruis had “lost sight of … what our commitment is to customers.” He was “taking the business in the wrong direction” and it was showing up in the financials.

Heather claimed she’d been powerless to stop Ruis: “I was gone formally for over a year and informally for two and a half years in the sense that I was pulling back and not able to influence things.”

I scarcely know where to start. We could talk about the breathtaking ease with which Heather presented herself as a victim of Ruis while running him over with a forklift. How she hired a career fashion retailer to run what most Canadians still understand as a book chain and complained that he took the business off brand. How his barbecues and dildo merchandising was a logical extension of the cheeseboards and blankets merchandising she’d been doing for a decade.

If we were a serious business publication, we’d have to talk about her supposed powerlessness to do anything about the dildo-happy Ruis. The people who run public companies have duties to their shareholders, one of which is to keep them informed—promptly, honestly, transparently—about the management of the business. If Heather was gone “formally for over a year” and “informally for two and a half years,” investors should have known, right?

Let’s start with “formally for over a year.” Heather is referring to the most recent period of September 2022 to August 2023 during which Barbecue Boy was CEO of the company. Was Heather gone?

She was no longer CEO, a title she’d held for a quarter century, but according to corporate records she remained executive chairman of Indigo during that time, drawing an annual salary of almost a million. Titles matter in public companies. The difference between an executive chairman and a run-of-the-mill chairman is that the former is recognized as having an active role in the operations of the business, hence the executive-level salary. Executive chairman is higher on the org chart than CEO. If the company was moving off brand, betraying its customers, she was the one person with the formal role and the moral authority, as founder, to send the “four hours of fun” Firefighter Vibrator from Smile Makers ($75.00) back to the warehouse. Either Heather misspoke to Amanda last week about being “gone” or she spent her last year at Indigo misrepresenting herself to her shareholders and drawing a salary under false pretenses.

September 24, 2023

A sliver of hope for Indigo?

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte relays some new-ish rumours in the book business that may provide a bit of help for the struggling Indigo chain:

“Indigo Books and Music” by Open Grid Scheduler / Grid Engine is licensed under CC0 1.0

So what do we make of Heather Reisman’s return as CEO of the Indigo bookselling chain after her unceremonious removal from that role just two months ago?

The short answer is I have no idea, but SHuSH has never shied away from delivering irresponsible speculation on happenings at Indigo. I heard this week from a reasonably reliable source that Indigo is in discussions with Elliott Management Corp., owners of Barnes & Noble and the world’s only buyer of distressed bookselling chains.

This conflicts with some chatter I reported last spring suggesting that Elliott Management was uninterested in Indigo. If what I’m now hearing is true, it’s great news.

I have to emphasize, I have no idea. But if a deal were imminent, it would make sense to bring Heather back to see it through. Indigo wouldn’t want the bother of recruiting a new leader simply to effect the handover, and who would want the job on those terms?

And another thing …

In last week’s piece about Indigo, I noted that the company’s staff, “with exceptions, were young, inexpert, and disinterested”. Amal, clearly one of the exceptions, left an interesting comment:

No. We became disinterested simply because a) we were all book lovers and had zero interest in selling crap and b) just like the author of this piece, head office and management were beyond dismissive of our knowledge, our book expertise, our genuine love of the written word. I worked at Chapters/Indigo starting in 2006 all the way until 2019, a couple of days a week, simply for my love of books. I am incredibly proud of my time there — especially when I was able to introduce new authors or genres to readers. My staff picks would sell out because I would hand sell them to people with my joy. It certainly wasn’t for the stellar pay or the people who treat retail employees like we are “inexpert”. Fun fact: you were asked in the job interview what your favourite books/genres were.