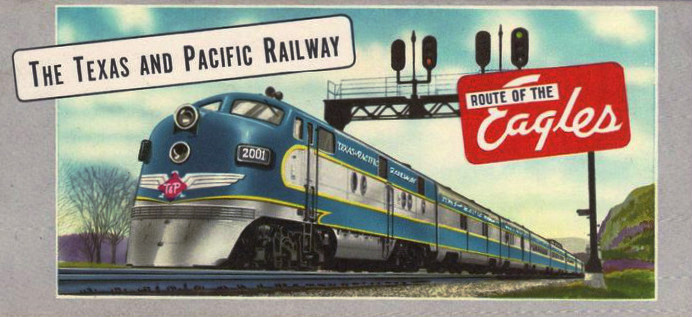

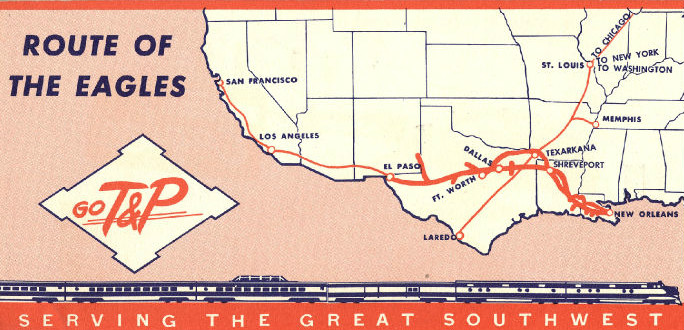

This month’s fallen flag article for Classic Trains is the story of the Texas & Pacific Railway by J. Parker Lamb:

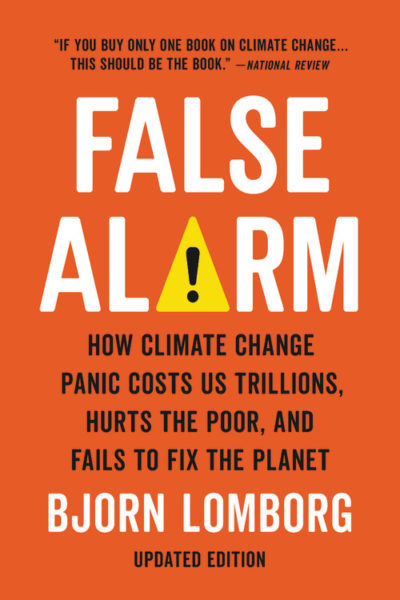

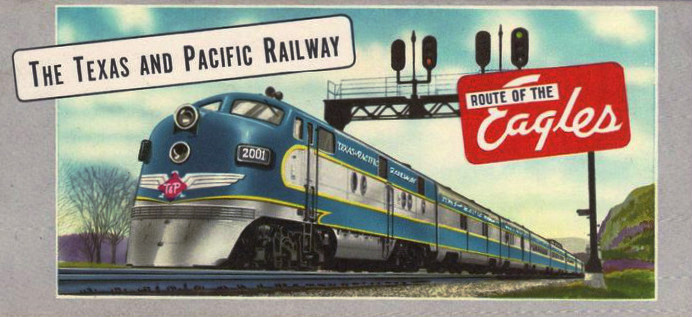

Decorative ticket cover for a Texas & Pacific passenger train. T&P passenger trains were called “Eagles”, as in the Texas Eagle.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

What grew to become the 20th century’s Texas & Pacific Railway sprouted from some of Texas’s earliest railroads. The Lone Star State’s pre-Civil War network included 11 operating companies. One of the earliest was the Texas Western Railroad, chartered in 1850 and soon renamed Vicksburg & El Paso. In 1856 its name changed again, to Southern Pacific Railroad Company. Of course, this SP had no relation to the Southern Pacific incorporated in 1865 in California, although the convoluted histories of their successors later would intersect.

Backers of this railroad envisioned it as part of a southern transcontinental route from the Mississippi River to San Diego. By 1860, construction of 27 miles was completed between Waskom, on the Louisiana border, and Marshall. The eastern connection was planned as the Vicksburg, Shreveport & Pacific, which already stretched from Waskom across Louisiana to the west bank of the Mississippi at Vicksburg (later part of Illinois Central, it is now part of Kansas City Southern’s “Meridian Speedway”).

The Memphis, El Paso & Pacific, chartered in 1856, planned to start at the Red River near Texarkana and build to a connection with the SP near Dallas, thereby bringing Midwestern traffic into the transcontinental route. Little progress was made before the Civil War, however, with only 5 miles of track built, near Jefferson.

Within a decade after the war, these two lines would be fused into one company. In 1870 the Memphis road was renamed Southern Transcontinental Railroad, and in 1872 Congress issued a charter for the Texas & Pacific Railway, which soon acquired both the ST and SP. The new charter approved a route from Marshall to El Paso and San Diego, and required 100 consecutive miles of construction by 1882. Backers hired Gen. Grenville Dodge, who had been chief engineer of Union Pacific’s recently completed transcontinental line to Utah.

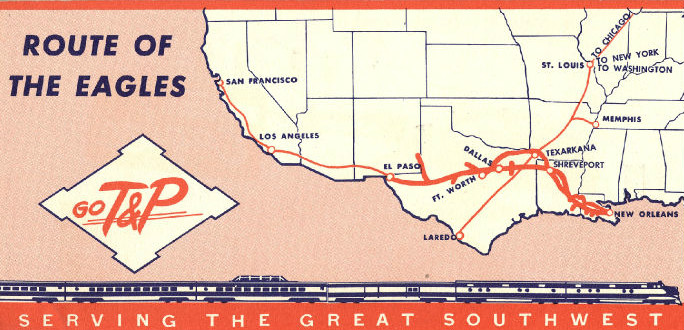

The route of the Texas & Pacific from the back of a ticket.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

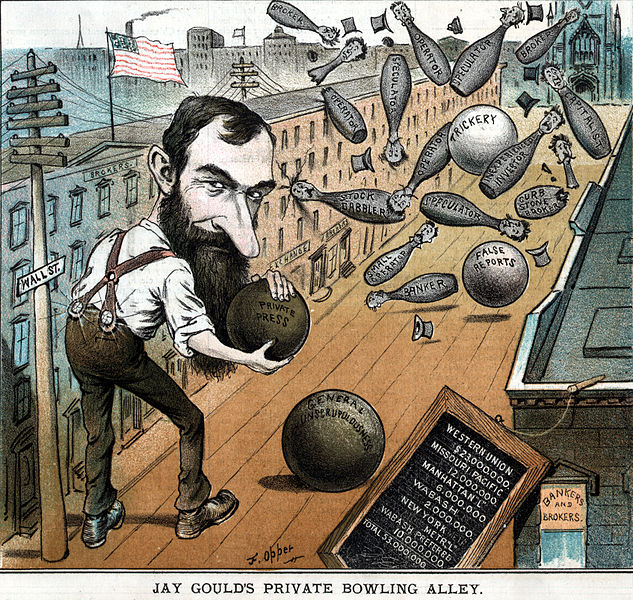

In 1880, the infamous “Robber Baron” Jay Gould joined the board and quickly became the president, and the T&P became a key part of his corporate empire (he already controlled the Union Pacific after 1873 and the Missouri Pacific from 1879):

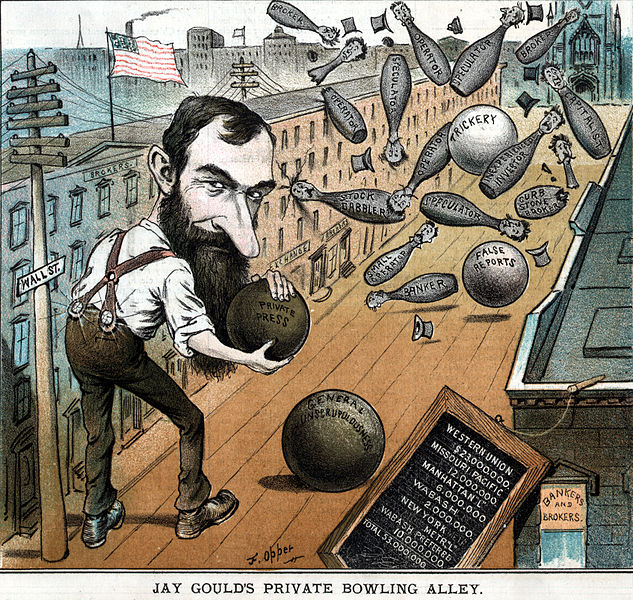

“Jay Gould’s Private Bowling Alley.” Financier and stock speculator Jay Gould is depicted on Wall Street, using bowling balls titled “trickery,” “false reports,” “private press” and “general unscrupulousness” to knock down bowling pins labeled as “operator,” “broker,” “banker,” “inexperienced investor,” etc. A slate shows Gould’s controlling holdings in various corporations, including Western Union, Missouri Pacific Railroad, and the Wabash Railroad.

From the cover of Puck magazine Vol. XI, No 264 via Wikimedia Commons.

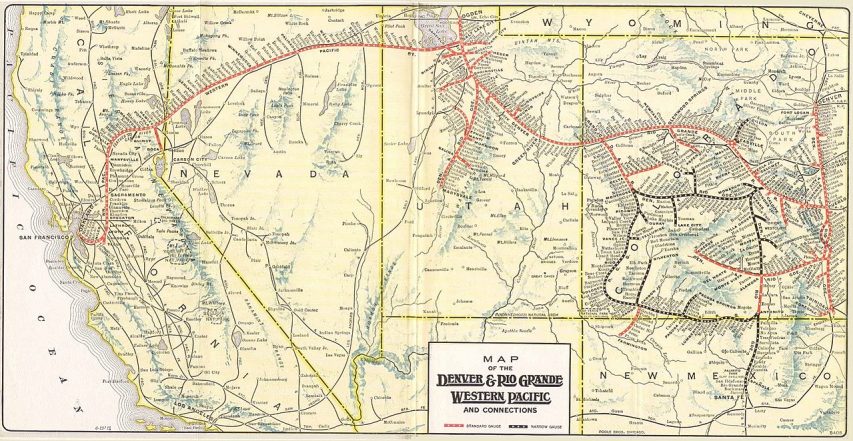

Meantime, Gould directed Chief Engineer Dodge to begin an all-out effort to lay rails through the vast and nearly uninhabited desert of west Texas. Construction crews reached Big Spring, 267 miles, in April 1881 and Sierra Blanca (522) on December 16, 1881. However, it was at Sierra Blanca where Gould’s dream of a transcontinental railroad evaporated. He had been bested by Collis P. Huntington, another determined and ruthless railroad tycoon. Huntington’s eastward construction crews had passed through Sierra Blanca three weeks earlier, on November 25, en route to their own “last spike” ceremony of the Sunset Route at the Pecos River (west of Del Rio) in January 1883.

Under the banner of the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio, controlled by Huntington and T. W. Pierce, construction crews had left El Paso in June 1881. When it was clear that Huntington was winning the race for a transcontinental line, a series of court battles ensued, followed by nefarious delaying tactics (including sabotage) by each construction crew, and finally by personal negotiation between the two principals. Gould’s legal case was based on T&P’s 1870 charter to build to San Diego, whereas Huntington’s Southern Pacific charter allowed him to meet the T&P at the Colorado River (between California and Arizona).

Wikipedia provides this sketch of Gould’s railway activities after his involvement in the Erie War:

After being forced out of the Erie Railroad, Gould started to build up a system of railroads in the midwest and west. He took control of the Union Pacific in 1873 when its stock was depressed by the Panic of 1873, and he built a viable railroad that depended on shipments from farmers and ranchers. He immersed himself in every operational and financial detail of the Union Pacific system, building an encyclopedic knowledge and acting decisively to shape its destiny. Biographer Maury Klein states that “he revised its financial structure, waged its competitive struggles, captained its political battles, revamped its administration, formulated its rate policies, and promoted the development of resources along its lines.”

By 1879, Gould gained control of three more important western railroads, including the Missouri Pacific Railroad. He controlled 10,000 miles (16,000 km) of railway, about one-ninth of the rail in the United States at that time, and he had controlling interest in 15 percent of the country’s railway tracks by 1882. The railroads were making profits and set their own rates, and his wealth increased dramatically. He withdrew from management of the Union Pacific in 1883 amid political controversy over its debts to the federal government, but he realized a large profit for himself. He obtained a controlling interest in the Western Union telegraph company and in the elevated railways in New York City after 1881. In 1889, he organized the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis which acquired a bottleneck in east–west railroad traffic at St. Louis, but the government brought an antitrust suit to eliminate the bottleneck control after Gould died.