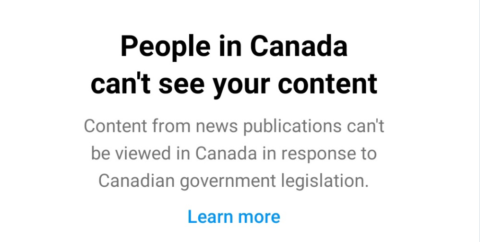

Tim Worstall discusses some of the issues ailing Canadian and American newspapers which are not easily solvable (government subsidies, as attempted in Canada, just turn the recipients into an underpaid PR branch of the governing party … not a good look in a democratic nation):

So, as a little corrective, a quick jaunt through what actually ails American journalism. The concentration is upon the big newspapers because that’s where the problem is worst. The conclusion is that it’s gonna get a lot, lot, lot, worse too. Because the industry is facing a base economic problem that it’s not willing to actually face up to. Or, at least, all the journalists writing about it aren’t — there’s the occasional sign that some of the business side of the equation grasp it.

[…]

Before Y2K American newspapers were segmented along geographic lines. The size of the country, the lack of a long distance passenger railroad network, meant that this was just so. If you’re printing a daily paper then you’ve got to deliver it daily. On the day it’s meant to refer to as well. If Chicago is 1,100 miles (no, I’ve not looked it up but that’s within an order of magnitude of being right, which is better than many newspapers manage with numbers) from New Orleans then the same newspaper is going to find it difficult to print and deliver to both markets. Add in the fact that trains take a week to traverse that distance, passenger trains – anyone who has ever travelled Amtrak will say it feels that long at least — included.

You could not and therefore did not have national newspaper (USA Today, with satellite printing plants, was an attempt to deal with this and slightly earlier than our cut off date but doesn’t change the basic story) distributions. What you had was a series of local and regional monopolies. Each one centred on a large population centre and serving the area around it that could be reasonably reached by truck overnight. Chicago and Cincinnati, not 1,100 miles away from each other, did have entirely different newspapers.

By contrast, and just as an example, the British newspaper market was national from pre-WWI. We simply did have overnight at worst passenger rail that covered the country. Partly it’s a much, much, smaller place, partly the passenger rail system was just different. So, printing overnight (and some maintained separate Scottish editions and plants) meant that those papers that came off the press in London at 8pm were on sale in Glasgow at 8 am, those that came off the press in London at 4 am were on sale in London at 8am. That’s not exact but it’s a good enough pencil sketch.

Cincinnati newspaper(s) served Cincinnati. Chicago, Chicago and New Orleans the area of New Orleans. There simply wasn’t a “national press” in the US in that British sense.

OK. But this also meant that American newspapers were much more like a monopoly in their local area than anything else. Network effects still exist even before computer networks after all. The most important of which was the classifieds.

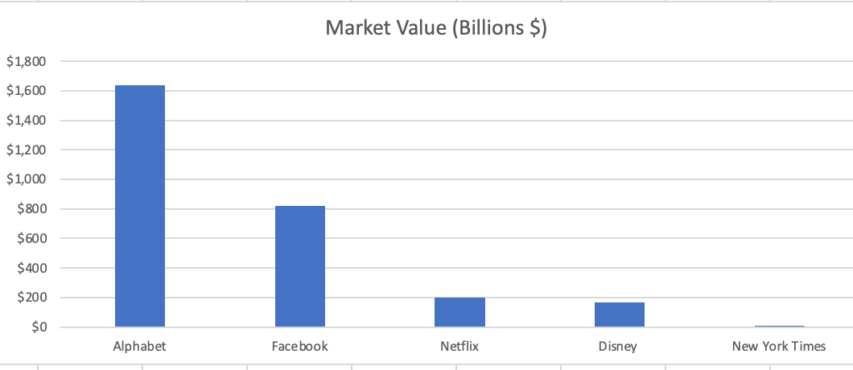

As with Facebook, we’re all on Facebook because everyone else is on Facebook. So, if we’re to join a social network we’re going to be on Facebook where everyone else is — except those three hipsters who are where it isn’t cool yet. This applies to classifieds sections. Folk advertise in the one with the most readers, the widest market. Readers buy the one with the most ads in it, the widest market. You advertise the bronzed baby shoes, unused, where there are the most people looking for bronzed baby shoes, unused.

So, the dominant paper will suck up the classifieds in any particular market. Classifieds, fairly obviously back in the days of prams, cheap used cars, waiters’ jobs and so on being geographically based.

No, this is important. A useful pencil sketch of American newspaper revenues pre-Y2K was that subscriptions produced some one third of revenues. They also, around and about, covered print costs and distribution. They were, roughly you understand, about a face wash in fact.

Display ads produced another one third and classifieds the final one third. Classifieds were also wildly profitable — no expensive journalists to pay, no bureaux, just a few women waiting to get married on the end of the phone line.