Sabaton History

Published 29 Sept 2022Fritz Haber is a controversial historical figure. He was responsible for scientific advances that fed billions, yet he created weapons of mass destruction that filled millions with terror. This is his story.

(more…)

October 1, 2022

“Father” – Fritz Haber – Sabaton History 113 [Official]

Tank Chat #154 | Valentine DD | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 27 May 2022We’re back with another Tank Chat this week! Catch up with Historian David Fletcher as he chats in detail about the Valentine DD tank.

(more…)

September 27, 2022

Arex Delta Gen2: How Gun Designs Iterate and Improve

Forgotten Weapons

Published 25 May 2022In firearms, as in really all technology, the market iterates and improves concepts over time. A novel new system — like the polymer-framed, striker-fired semiauto pistol — will never be perfect on its first introduction. Over time, as users and manufacturers gain more insight into the details of using and building the system, changes are made to improve it. At the same time, the cost of production comes down (especially after applicable patents have expired).

The Arex Delta Gen2 pistol is a really good example of this, I think. While offering no fundamental innovation, it is markedly better in all sorts of ways than similar pistols that preceded it. It has great handling, safe disassembly, near-universal optics compatibility, slim lines, light weight, and a good trigger. And it does this for a remarkably low price.

I am looking forward to really putting one through the wringer at Slovenian Brutality this June!

(more…)

September 7, 2022

The Original Caesar Salad from Mexico

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 6 Sep 2022

(more…)

September 4, 2022

Experimental Primer-Actuated Semiauto Springfield 1903

Forgotten Weapons

Published 3 Sep 2016During the 1920s, a lot of experimental rifle development work was being done in the US. The military was interested in finding a semi-automatic rifle, and plenty of inventors were eager to get that valuable military contract. One particular item of interest to the military was the possibility of being able to convert large existing stockpiles of bolt-action 1903 Springfield rifles into semi-automatics, and that is what this particular example was an attempt at.

This rifle is built with a barrel and receiver made in 1921 (it was not uncommon for the government to provide parts to inventors working in this area), and uses an operating system which is pretty much unheard of today: primer actuation. In this system, the primer pushes back out of the cartridge case (intentionally) upon firing, acting as a small piston. This pushes the firing pin backwards (as well as the bolt face in this rifle), which begins the process of unlocking and cycling. It is a system that saw some popularity for a brief time in the 20s, as it allowed semi-automatic action without the need for a drilled gas port or a moving barrel — several of John Garand’s early prototypes operated this way. However, substandard performance and the need for special ammunition (most military ammunition had primers solidly crimped in place) led to its abandonment.

(more…)

August 24, 2022

A Floating Airfield Made of Ice – WW2 Newsflash

World War Two

Published 23 Aug 2022In 1943, the British are working on a radical plan which could revolutionize the Allies’ productive capacity. It might sound crazy, but ice might be the magic material they need.

(more…)

August 20, 2022

The historical tourist attractions of Pisa

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes talks about a recent trip to Italy, specifically the historically interesting places in Pisa and Lucca:

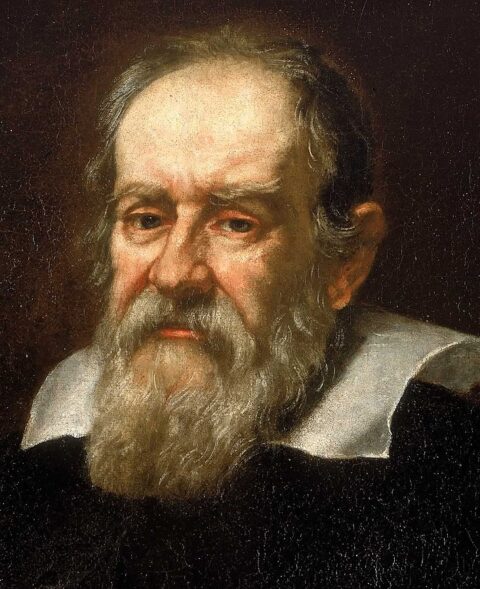

Galileo Galilei circa 1640.

Detail of an oil portrait by Justus Sustermans (1597-1681) from the National Maritime Museum via Wikimedia Commons.

Some are famous. Galileo Galilei, for example, is said to have used the leaning tower of Pisa to drop two spheres of different masses, to show that they would fall at the same speed — at least, that’s what his disciple Vincenzo Viviani claimed, ten years after Galileo’s death, and many decades after the alleged demonstration. Even if Viviani was being accurate, however, Galileo certainly wasn’t the first to demonstrate the concept. And Viviani mistakenly claimed priority for all sort of other scientific breakthroughs for his master, so like most other historians I’m inclined to doubt the story.

Nonetheless, Pisa was certainly Galileo’s birthplace — though it turns out that there are three different locations in the city to have claimed the honour over the years.

Galileo was initially thought to have been born in or near the fortress (its walls are impressive to look at and contain a pleasant garden). But this location was then refuted on the basis that for Galileo’s father Vincenzo Galilei to have lived in the fortress he would have had to have been a master at arms, which he was not. He was in fact a merchant and lute-maker. So in the nineteenth century a new location emerged: the casa Bocca, on the Stretto Borgo, which Vincenzo rented a few months before Galileo’s birth, and where the Galilei family lived for the next decade. It seemed a secure candidate for a while, except for a weird discrepancy: Galileo’s baptismal certificate assigned his birth to the wrong parish.

It then emerged that Galileo’s mother’s family — the Ammannati — lived in the correct parish, and that the custom of the time was for women to return to their parents’ home for the birth of their first child. Thus, the evidence points to Galileo having been born at the Casa Ammanati on the via Giusti. It’s a neat story of how a tourist destination can jump around based on new research, though there’s unfortunately not much to visit there other than a plaque.

In terms of things to actually see, one of the most impressive things in Pisa is the Museo delle Navi Antiche (Museum of Ancient Ships), which we found to be undeservedly deserted. Housed in the old stables for the city’s cavalry, and once the site of the Medici-era naval arsenal, the museum gives a fantastically thorough overview of the city from its Etruscan beginnings through to Roman subjugation, Ostrogothic invasion, Byzantine reconquest, and Longbeard settlement in the sixth century (although they’re usually called the Lombards, this comes from langobardi — literally, longbeards — so I think calling them that is both more accurate and more fun).

The museum’s highlight, however, is the ancient ships for which it is named, and which are incredibly well-preserved. I was stunned to see a massive actual wooden anchor, not just a reconstruction, of a cargo ship from the second century BC. It’s so well-preserved that you can even make out a decoration, carved into the wood, of a ray fish. The same goes for the rest of the various ships’ timbers. You can see almost all of their original hulls and planking, as well as finer details like rudder-oars, benches for the rowers, and in one case even the ship’s name carved into the wood — the Alkedo, which appears to have been a pleasure boat from the first century. Apparently, during excavation, the archaeologists could even make out the Alkedo‘s original red and white paint, as well as the impression left by an iron sheet that had covered its prow. The ships’ contents are often just as astonishing, with well-preserved baskets, fragments of clothing, and even bits of the rigging like its wooden pulleys and ropes. Well worth a visit.

August 18, 2022

The bridge design that helped win World War II

Vox

Published 12 Mar 2021It’s a simple innovation that helped win a war.

The Bailey bridge was Donald Bailey’s innovative solution to a number of wartime obstacles. The allies needed a way to cross bodies of water quickly, but bombed-out bridges — or an absence of crossings entirely — made that incredibly difficult. That was only compounded by new, heavy tanks that needed incredibly strong support.

Bailey’s innovation — a modular, moveable panel bridge — solved those problems and gave the allies a huge advantage. The 570-pound steel panel could be lifted by just six men, and the supplies could fit inside small service trucks. Using those manageable materials, soldiers could build crossings sufficient for heavy tanks and other vehicles.

As impressive, the Bailey bridge could be rolled across a gap from one side to the other, making it possible to build covertly or with little access to the other side. Together, all the Bailey bridge’s advantages changed bridge construction and may have helped win the war.

(more…)

July 30, 2022

Beartrap: The Best Way To Land A Big Helicopter On A Small Ship At Sea

Polyus Studios

Published 29 Jul 2022Don’t forget to like the video and subscribe to my channel!

Support me on Patreon – https://www.patreon.com/polyusstudiosToday, navies across the world use an ingenious system to land helicopters on the rolling deck of a ship at sea. It enabled the powerful helicopter-destroyer combination that has become the dominant form of at sea anti-submarine warfare. It’s the “helicopter haul down and rapid securing device”, more commonly known as Beartrap. This device may be little known to the public, but it stands as one of the greatest contributions Canada has ever made to naval aviation, and ushered in the age of helicopters at sea.

(more…)

July 24, 2022

Stoner 63A Automatic Rifle – The Original Modular Weapon

Forgotten Weapons

Published 17 Mar 2018The Stoner 63 was a remarkably advanced and clever modular firearm designed by Eugene Stoner (along with Bob Fremont and Jim Sullivan) after he left Armalite. This was tested by DARPA and the US Marine Corps in 1963, and showed significant potential — enough that the US Navy SEALs adopted it and kept it in service into the 1980s. It was a fantastic balance of weight and controllability, offering a belt-fed 5.56mm platform at less than half the weight of the M60. The other fundamental characteristic of the Stoner 63 was modularity. It was built around a single universal receiver component which could be configured into a multitude of different configurations, from carbine to medium machine gun. Today we have one of the rarer configurations, an Automatic Rifle type. In addition, today’s rifle is actually a Stoner 63A, the improved version introduced in 1966 to resolve some of the problems that had been found in the original.

Ultimately, the Stoner system was able to achieve its remarkably light weight by sacrificing durability. The weapon was engineered extremely well and was not a danger to itself (like, for example, the FG-42), but it was prone to damage when mishandled by the average grunt. This would limit its application to elite units like the SEALs, who were willing to devote the necessary care to the maintenance and operation of the guns in exchange for the excellent handling characteristics it offered.

(more…)

July 22, 2022

QotD: Spoiler – there was no technological solution to trench warfare in WW1

On the one hand, the later myth that the German army hadn’t been defeated in the field was nonsense – they had been beat almost along the entire front, falling back everywhere. Allied victory was, by November, an inevitability and the only question was how much blood would be spilled before it happened. On the other hand, had the German army opted to fight to the last, that victory would have been very slow in coming and Foch’s expectation that a final peace might wait until 1920 (and presumably several million more dead) might well have been accurate. On the freakishly mutated third hand, it also seems a bit off to say that [the French doctrine of] Methodical Battle had won the day; it represented at best an incremental improvement in the science of trench warfare which, absent the blockade, potentially endless American manpower and production (comparatively little of which actually fought compared to the British and the French, even just taking the last Hundred Days) and German exhaustion might not have borne fruit for years, if ever.

All of which is to say, again, that the problem facing generals – German, French, British and later American – on the Western Front (and also Italian and Austrian generals on the Italian front) was effectively unsolvable with the technologies at the time. Methodical Battle probably represented the best that could be done with the technology of the time. The technologies that would have enabled actually breaking the trench stalemate were decades away in their maturity: tanks that could be paired with motorized infantry to create fast moving forces, aircraft that could effectively deliver close air support, cheaper, smaller radios which could coordinate those operations and so on. These were not small development problems that could have been solved with a bit more focus and funding but major complexes of multiple interlocking engineering problems combined with multiple necessary doctrinal revolutions which were in turn premised on technologies that didn’t exist yet which even in the heat of war would have taken many more years to solve; one need merely look at the progression of design in interwar tanks to see all of the problems and variations that needed to be developed and refined to see that even a legion of genius engineers would have required far more time than the war allowed.

It is easy to sit in judgement over the policy makers and generals of the war – and again, to be fair, some of those men made terrible decisions out of a mix of incompetence, malice and indifference (though I am fascinated how, in the Anglophone world, so much of the opprobrium is focused on British generals when frankly probably no British commander even makes the bottom five worst generals. Most lists of “worst generals” are really just “generals people have heard of” with little regard to their actual records and so you see baffling choices like placing Joseph Joffre who stopped the German offensive in 1914 on such lists while leaving Helmuth von Moltke who botched the offensive off of them. Robert Doughty does a good job of pointing out that men like Haig and Foch who were supposedly such incompetent generals in 1915 and 1916 show remarkable skill in 1918).

But the problem these generals faced was fundamentally beyond their ability or anyone’s ability to solve. We didn’t get into it here, but every conceivable secondary theater of war was also tried, along with naval actions, submarines, propaganda, and internal agitation. This on top of the invention of entirely new branches of the army (armor! air!) and the development of almost entirely new sciences to facilitate those branches. Did the generals of WWI solve the trench stalemate? No. But I’d argue no one could have.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: No Man’s Land, Part II: Breaking the Stalemate”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-09-24.

July 17, 2022

Earlier almost-steam-engine developments

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes picks up the story of the development of the steam engine (part one was linked here):

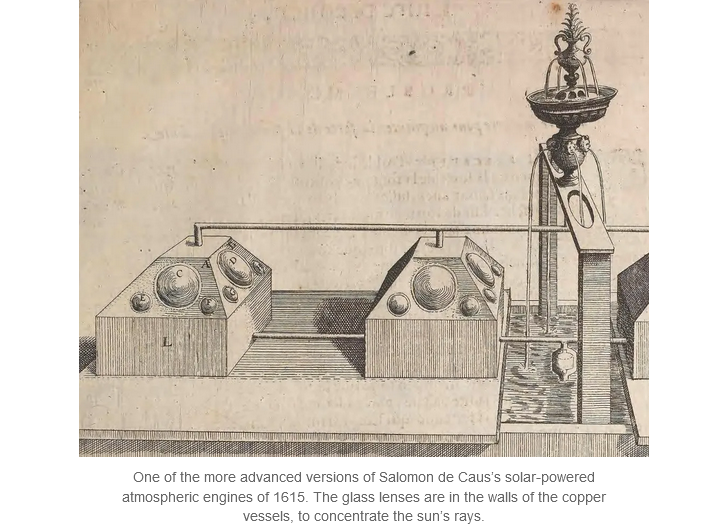

As I explained in Part I, the spark for my investigation was noticing that one Salomon de Caus, as early as 1615, had very probably made what amounts to a solar-powered version of Savery’s engine. By concentrating the sun’s rays on trapped air above the water in copper vessels, the resulting expansion of the trapped air and steam drove the water up a pipe to make a fountain flow. Most crucially of all, however, when the vessels cooled again they sucked water up and into them from a cistern below — a principle that de Caus also applied to having statues make music when the sun shone, and which he hinted may be useful for other things too.

Noticing this machine was a big shock to me, but de Caus’s invention was not even that original. It was actually an improvement of another, almost entirely ignored device described by Hero of Alexandria as early as the 1st Century, and which Hero in turn derived from one Philo of Byzantium who wrote in the 3rd Century BC.

Philo’s original device was very simple: a hollow leaden sphere with a bent tube rising out of it and into some water at the bottom of a jug. As the sun heated the sphere, the expanding air was pushed up the tube and into the jug’s water, escaping by bubbling out of the water. And crucially, when the sphere was removed from the sun and allowed to cool, the water was then drawn up the tube and into the sphere — Philo, about 1,900 years before Savery, had already encapsulated in a simple model the power of condensation to raise water.

Philo’s device was simple, but the principles it illustrated do appear to have been applied. Hero’s work, for example, includes a libas, or “dripper” fountain. In this alternative version of Philo’s apparatus, Hero connected the jug and sphere by two other pipes to a cistern underneath, as well as starting with some water already in the sphere. The jug now acted more like a funnel, into which the original bent tube now dripped its water like a fountain when the sun shone on the sphere. When cooled, however, the sphere replenished itself from the cistern underneath. It was almost exactly like de Caus’s version, which merely improved the strength of the fountain when it was heated, seemingly by replacing the lead with more heat-conductive copper and by using glass convex lenses to concentrate the sun’s rays.

Hero’s solar-powered dripping fountain doesn’t sound all that impressive, but both Philo and Hero appreciated the wider potential of its underlying principles.

Philo, for example, noted that it might make use of alternative heat sources: he described how his apparatus would work whether pouring hot water over the sphere, or by heating it over a fire. Once it cooled, it would always draw the water up.

Hero even suggested a mechanical use for the effect. By setting a fire on a hollow, airtight altar, the heated air within would flow down a tube into a sphere full of water, which in turn would be pushed up another tube into a hanging bucket. The bucket, when sufficiently heavy with water, would then pull on a rope to open some temple doors. Crucially, when the fire was extinguished, Hero noted that the cooling of the air in the altar would draw the water back into the sphere again, lighten the bucket, and so allow the doors to be closed by a counterweight. Although the condensing phase was really just for resetting the device, the fundamental ideas behind a Savery engine were already there: it raised water, used a fuel, and exploited condensation. It even did some light mechanical work.

July 16, 2022

Anti-Tank Chats #4 Bazooka | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 18 Mar 2022Join Stuart Wheeler for an Anti-Tank Chat and discover the US military’s development of the Bazooka anti-tank weapon.

(more…)

July 9, 2022

Tank Chat #151 Plastic Tank | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 11 Mar 2022► TIMESTAMP:

00:00 – INTRO

00:43 – FEATURES► SHOP THE TANK MUSEUM: tankmuseumshop.org

► JOIN OUR PATREON: Our Patreons have already enjoyed Early Access and AD free viewing of our weekly YouTube video! Consider becoming a Patreon Supporter today: https://www.patreon.com/tankmuseum

► FOLLOW THE TANK MUSEUM:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/tankmuseum/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/TankMuseum

Website: https://tankmuseum.org/

________________________◈ Created by The Tank Museum

#tankmuseum #tankchats #DavidFletcher

July 5, 2022

QotD: The Great Enrichment

The explanation of the Great Enrichment is people. Paul Romer says so, as do a few others, among whom are some students I did not teach price theory to at the University of Chicago. On the other hand, Paul sets it down to economies of scale, which mysteriously drop down on England in the 18th century and gradually on us all. Yet China had peace, science, and enormous cities when Europeans were huddled in small groups inside town walls, or isolated villae.

In particular, it is ideas that people have for commercially tested betterment that matter. Consider alternating-current electricity, cardboard boxes, the little black dress, The Pill, cheap food, literacy, antibiotics, airplanes, steam engines, screw-making machines, railways, universities, cheap steel, sewers, plate glass, forward markets, universal literacy, running water, science, reinforced concrete, secret voting, bicycles, automobiles, limited access highways, free speech, washing machines, detergents, air conditioning, containerization, free trade, computers, the cloud, smart phones, and Bob Gordon’s favorite, window screens. …

And the Great Enrichment depended on the less famous [but] crucial multitudes of free lunches prepared by the alert worker and the liberated shopkeeper rushing about, each with her own little project for profit and pleasure. Sometimes, unexpectedly, the little projects became big projects, such as John Mackey’s one Whole Foods store in Austin, Texas resulting in 479 stores in the U.S. and the U.K., or Jim Walton’s one Walmart in Bentonville, Arkansas resulting in 11,718 stores worldwide.

Letting people “have a go” to implement such ideas for commercially tested betterment is the crux. It comes, in turn, from liberalism, Adam Smith’s “obvious and simple system of natural liberty”, “the liberal plan of [social] equality, [economic] liberty, and [legal] justice”. Liberalism permitted, encouraged, honored an ideology of “innovism” — a word preferable to the highly misleading word “capitalism,” with its erroneous suggestion that the modern world was and is initiated by piling up bricks and bachelors’ degrees.

Dierdre McCloskey, “How Growth Happens: Liberalism, Innovism, and the Great Enrichment (Preliminary version)” [PDF], 2018-11-29.