Published on 25 Aug 2016

Hiawatha wanted peace, but a more powerful chief named Tadodaho opposed him. So he joined forces with a man called the Peacemaker and a woman named Jigonsaseh, who dreamed of uniting the five Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) nations under one Great Law of Peace.

CORRECTION: Art for this series was incorrectly credited. This art was done by Lilienne Chan.

____________Long before Europeans arrived in North America, five nations formed a confederacy guided by a Constitution called the Great Law of Peace. Though they are often called Iroquois, their name for themselves is Haudenosaunee, People of the Long House. One of the founders of their confederacy was Hiawatha, an Onondaga chief who lived under the thumb of a brutal war chief named Tadodaho. Hiawatha attempted to convince all the other Onondaga that they should embrace peace, the way their neighbors the Mohawks recently had, but Tadodaho thwarted his efforts. Hiawatha left his home to travel to Mohawk territory and meet a man called the Peacemaker, who had brought peace to the Mohawk. He gave the Peacemaker a string of wampum beads to symbolize his desire for peace, and it soon became clear that they were kindred spirits. The Peacemaker wanted to bring the Five Nations, who had once been brothers, together in peace, and he joined forces with Hiawatha to make it happen. Their first goal: to recrut Jigonsaseh, a Seneca woman already famed for her efforts to establish small, local peace agreements between the warriors who frequented her long house. The Peacemaker described to her his plans for a government where women like her, as clan mothers, played an important role, and she embraced his message. Together they traveled to the Oneida to recruit their first ally. The Oneida debated the wisdom of accepting peace for a full year, but the Peacemaker’s passion convinced them and at last they joined. Hiawatha hoped that this alliance would impress Tadodaho enough to get him to join the peace as well, but when they returned to Onondaga territory, Tadodaho made it clear that he still had no interest in their peace. The Peacemaker encouraged Hiawatha to keep thinking about this problem, and meanwhile they traveled to recruit the Cayuga nation. As “little brothers” of the Onondaga, they had suffered greatly from Tadodaho’s demands, and an alliance with two other nations struck them as the perfect way to free themselves from him and create a new path for their people. Now only two tribes remained to recruit: the Seneca and the Onondaga.

September 24, 2016

Hiawatha – I: The Great Law of Peace – Extra History

July 19, 2016

The Best Sniper Of World War 1 – Francis Pegahmagabow I WHO DID WHAT IN WW1?

Published on 18 Jul 2016

Francis Pegahmagabow was not only the most successful sniper of World War 1, but he is also among the most decorated aboriginal soldiers in history. He joined the Canadian Army in 1914 and quickly made a name for himself as a sniper during reconnaissance missions.

June 24, 2016

“[W]hite activists [need to] stop casting Indigenous peoples as magical pixie enviro-pacifists”

Jonathan Kay on the problem with discussing First Nations people as if they are “Magical Aboriginals”:

… the path toward reconciliation doesn’t always run through Ottawa or Rome. Reconciliation also can take place at the level of friends, family members and neighbours. In a newly published collection of essays, In This Together, editor Danielle Metcalfe-Chenail brings together fifteen writers — some Indigenous, some not — who describe how this process has played out in their own lives. “[The authors] investigate their ancestors’ roles in creating the country we live in today,” Metcalfe-Chenail writes in her introduction. “They look at their own assumptions and experiences under a microscope in hopes that you will do the same.”

In This Together is a poignant and well-intentioned book, and one that deserves to be bought and read. It is also informative and unsettling — though not always in the way the authors intend. Taken as a whole, the stories betray the extent to which guilt, sentimentality and ideological dogma have compromised the debate about Indigenous issues in this country.

[…]

In describing the stock “Magical Negro” who often appears in popular books and movies, Nnedi Okorafor-Mbachu once noted that this type of character typically is shown to be “wise, patient, and spiritually in touch, [c]loser to the earth.” (Think of Morgan Freeman’s portrayal of Ellis Boyd “Red” Redding in The Shawshank Redemption.) In This Together contains a menagerie of similarly magical-seeming Aboriginals who are “soft-spoken” and “insightful.” A typical supporting character is the hard-luck Aboriginal child whose “entire face seemed to radiate a quiet knowing.” Older characters speak in Yoda-like snippets such as “There is much loss — but all is not lost.”

White characters in this book mostly are presented in the opposite way. They tend to be cruel, obese (“bulging,” “fat, red-faced,” “plump”), and soulless. Streetly goes even further, describing outsiders who come to Tofino as “faceless, meaningless” — as if they were robots. In a story about a First Nations woman with the dermatological condition vitiligo, Carol Shaben casts whiteness as an imperial disease — “an ever-expanding territory of white colonized the brown landscape of her skin.” In matters of economics, whites often are depicted as amoral capitalist marauders (“quick to brand and claim ownership”), while Indigenous peoples are presented as inveterate communitarians — gentle birds who “soar above the land, take stock, perch without harming, settle without ownership, and be grateful without exploitation.”

[…]

For decades, it has been a point of principle that Indigenous peoples in Canada must chart their own future without interference from outsiders. Our First Nations will have to make difficult decisions about what mix of traditional and modern elements they want in their society; and address wrenching questions about integration, relocation, language use, and education. Addressing these hard questions will be all the more difficult if Canada’s leading thinkers — even those with the best of intentions, such as the authors of In This Together — build the project of reconciliation on a foundation of attractive myths.

It is our moral duty as a Canadians to acknowledge the full horror of what was done to Indigenous peoples. But we must not respond to this horror by seeking to conjure an Indigenous Eden of postcolonial imagination — a society that never truly existed in the first place.

October 7, 2015

Argentina’s colonial history

Ralph Peters on the history of Argentina during the colonial era:

In the 19th century in the Western hemisphere, two states fought a protracted series of wars to subdue their frontiers, the United States and Argentina. Others, such as Chile or Canada, saw lesser violence, but the great wars of conquest were directed from Washington and Buenos Aires.

And the Argentine conquest appears to have been the crueler.

Settlers in the Spanish territory that became Argentina faced Indian threats from the beginning, but as the population swelled and expanded its territorial claims, the violence grew more frequent and extreme, with Indian raids on settlers similar to those experienced on the American frontier. Finally, in 1833, Juan Manuel de Rosas — a man of great vision and spectacular brutality who would rule Argentina as dictator — launched his “Desert Campaign,” which pushed back the frontier to Patagonia. Still, Indian raids continued, on and off, as did minor punitive expeditions, until the 1870s saw the years-long campaign, the “Conquest of the Desert,” that finally mastered all of Patagonia — which would become Argentina’s agricultural heartland, facilitating a turn-of-the-century economic boom.

Those wars saw a long list of massacres, atrocities, forced removals and the treatment of Argentina’s aboriginal peoples as animals, rather than humans.

When the Pope told Americans not to judge the past by today’s standards, we thought of our “Trail of Tears,” or of the last, murderous drives to contain our Indians on bleak reservations. But the Pope saw mounted troops in Argentine uniforms hunting down natives like game animals.

November 2, 2014

Pre-game program in Minneapolis

The Washington Redskins are in Minneapolis today to face the Minnesota Vikings. Both teams have 3-5 win/loss records and both are coming off wins last weekend. However, this weekend’s pregame festivities will include protests against the Washington team name:

The Washington Redskins are in Minneapolis today to face the Minnesota Vikings. Both teams have 3-5 win/loss records and both are coming off wins last weekend. However, this weekend’s pregame festivities will include protests against the Washington team name:

People who want Washington to abandon the Redskins nickname are taking their protest to the streets.

After a rally at David Lilly Plaza, several hundred people are marching through the University of Minnesota campus to TCF Bank Stadium, where Washington plays the Minnesota Vikings. Four men banging a traditional drum and women carrying a banner reading, “No Honor in Racist Nicknames or Imagery” are leading the March to the stadium, about a mile away.

“Today it’s going to stop,” Clyde Bellcourt, co-founder of the American Indian Movement, said before the march began.

Update:

Wow. @MikeWiseguy: This is the scene of the largest ever physical gathering against the Wash. NFL team. pic.twitter.com/dEG2o01soW"

— Steve Wyche (@wyche89) November 2, 2014

The people protesting the non-bird friendliness of #Vikings new stadium drawing slightly less attention. pic.twitter.com/zWFkhhB5gS

— Tom Pelissero (@TomPelissero) November 2, 2014

July 5, 2014

The Tsilhqot’in Nation and British Columbia, now with legal standing and everything

When I saw the initial reports on the Supreme Court’s decision in Tsilhqot’in Nation versus British Columbia it sounded like the Supremes were ordering the province to pack up and move out … that most (all?) of the land previously known as British Columbia was now to be handed back to the First Nations bands. I guess it’s not quite so apocalyptic, although it will complicate things. Colby Cosh talks about the historical record that informed the decision:

Like everyone else who has studied the Supreme Court’s dramatic decision in the case of Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia, my response largely amounts to “Well, sure.” “Tsilhqot’in” is the new accepted name of the small confederacy of B.C. Indian bands long called the Chilcotin in English. They live in a scarcely accessible part of the province, and one reason it is scarcely accessible is that the Chilcotin prefer it that way. In 1864, they fought a brief “war” against white road builders, killing a dozen or so. The leaders of the uprising were inveigled into surrendering and appearing before the “Hanging Judge,” Matthew Begbie. True to his nickname, he executed five of the rebels. But that road never got finished.

In most of Canada, occupancy by “settlers” whose ancestors arrived after Columbus has been formally arranged under explicit treaties. There is a lot of arguing going on about the interpretation of these treaties. But, broadly speaking, most of us white folks outside B.C. have permission to be here. Our arrival, our multiplication and the supremacy of our legal system were all explicitly foreseen and consented to by representatives of the land’s Aboriginal occupants. The European signatories of those treaties recognized that First Nations had some sort of property right whose extinction needed to be negotiated.

Oddly, this concept was clearer to imperial authorities in the 18th and early 19th centuries than to those who came later. The Royal Proclamation of 1763, for instance, recognized the right of Indians to dispose of their own lands only when they saw fit. By the time mass colonization was under way in British Columbia, the men in charge on the scene had absorbed different ideas. Concepts of racial struggle were in vogue, and so were straitlaced, monolithic models of human progress.

And the problems going forward?

The biggest problem for large infrastructure projects in the B.C. Interior may not be the collective nature of “Aboriginal title” alone, but the fact that it is restricted in a way ordinary property ownership isn’t. “It is collective title,” writes the chief justice, “held not only for the present generation but for all succeeding generations. This means it cannot be alienated except to the Crown, or encumbered in ways that would prevent future generations of the group from using and enjoying it.” The special category of legal title devised for First Nations turns out to have a downside: Even completely unanimous approval of some land use by a band or nation may not suffice if people who do not yet exist are imagined disagreeing with it. Would you care to own a car or a house on such terms?

Update, 11 July: Perhaps I spoke too soon that this ruling didn’t mean the non-First Nation inhabitants need to move out of the province.

British Columbia First Nations are wasting no time in enforcing their claim on traditional lands in light of a landmark Supreme Court of Canada decision recognizing aboriginal land title.

The hereditary chiefs of the Gitxsan First Nations served notice Thursday to CN Rail, logging companies and sport fishermen to leave their territory along the Skeena River in a dispute with the federal and provincial governments over treaty talks.

And the Gitxaala First Nation, with territory on islands off the North Coast, announced plan to file a lawsuit in the Federal Court of Appeal on Friday challenging Ottawa’s recent approval of the Northern Gateway pipeline from Alberta.

The Kwikwetlem First Nation also added its voice to the growing list, claiming title to all lands associated with now-closed Riverview Hospital in Metro Vancouver along with other areas of its traditional territory.

They cite the recent high court ruling in Tsilhqot’in v. British Columbia.

[…]

In the short term, the ruling will impact treaty negotiations and development in the westernmost province, where there are few historic or modern treaties and where 200 plus aboriginal bands have overlapping claims accounting for every square metre of land and then some.

“Over the longer term, it will result in an environment of uncertainty for all current and future economic development projects that may end up being recognized as on aboriginal title lands,” wrote analyst Ravina Bains.

July 3, 2014

LGBT? LGBTQQI? LGBTQQIAP? Or even LGBTTIQQ2SA?

The coalition of lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and trans* people has a problem: the big tent approach requires that they acknowledge the members of their coalition more directly, leading to a situation where they’ve “had to start using Sanskrit because we’ve run out of letters.”

“We have absolutely nothing in common with gay men,” says Eda, a young lesbian, “so I have no idea why we are lumped in together.”

Not everyone agrees. Since the late 1980s, lesbians and gay men have been treated almost as one generic group. In recent years, other sexual minorities and preferences have joined them.

The term LGBT, representing lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender, has been in widespread use since the early 1990s. Recent additions — queer, “questioning” and intersex — have seen the term expand to LGBTQQI in many places. But do lesbians and gay men, let alone the others on the list, share the same issues, values and goals?

Anthony Lorenzo, a young gay journalist, says the list has become so long, “We’ve had to start using Sanskrit because we’ve run out of letters.”

Bisexuals have argued that they are disliked and mistrusted by both straight and gay people. Trans people say they should be included because they experience hatred and discrimination, and thereby are campaigning along similar lines as the gay community for equality.

But what about those who wish to add asexual to the pot? Are asexual people facing the same category of discrimination. And “polyamorous”? Would it end at LGBTQQIAP?

There is scepticism from some activists. Paul Burston, long-time gay rights campaigner, suggests that one could even take a longer formulation and add NQBHTHOWTB (Not Queer But Happy To Help Out When They’re Busy). Or it could be shortened to GLW (Gay, Lesbian or Whatever).

An event in Canada is currently advertising itself as an “annual festival of LGBTTIQQ2SA culture and human rights”, with LGBTTIQQ2SA representing “a broad array of identities such as, but not limited to, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual, transgender, intersex, queer, questioning, two-spirited, and allies”. Two-spirited is a term used by Native Americans to describe more than one gender identity.

Note that once you go down the rabbit hole of ever-expanding naming practices for ever-more-finely-divided groups you end up with the 58 gender choices of Facebook and instant demands to add a 59th, 60th, and 61st choice or else you’re being offensively exclusive to those who can’t identify with the first 58 choices. I’d bet that one of the criticisms Julie Bindel will face for this article is that she uses the hateful, out-dated, and offensive terms “transsexual” and “transgender” when everyone knows the “correct” term is now “Trans*” (perhaps deliberately chosen to ensure that you can’t successfully Google it).

June 19, 2014

March 5, 2014

MazaCoin is now the official currency of the Lakota nation

Adrianne Jeffries talks about a Bitcoin-like currency that the Lakota have adopted as their official currency:

The programmer and Native American activist Payu Harris raised a gavel Monday night and vigorously banged the bell to open trading at The Bitcoin Center, a meeting space for virtual currency geeks that looks like an empty art gallery in the middle of New York’s Financial District.

Harris was there to promote MazaCoin, a cousin of Bitcoin that is now the official currency of the seven bands that make up the Lakota nation. After an hour of questions, Harris thanked the small crowd and was promptly accosted by a tall man and a woman in red who wanted to buy some MazaCoin, which Harris was selling for 10 cents apiece. The two trailed him around the room as he hunted for a printer so he could issue the digital currency on paper. MazaCoin is a month-old cryptocurrency based on the same proof-of-work algorithm as Bitcoin, the virtual currency that approximates cash on the internet — but no one in the room was equipped to make a digital trade.

There have been a slew of copycats since the rise of Bitcoin in 2009. The first wave attempted to improve on the basic Bitcoin protocol. The second wave, which includes the meme-based Dogecoin and the Icelandic Auroracoin, are catering to specific groups.

October 17, 2013

QotD: Small town architecture

Damariscotta, Maine, is a village about forty percent of the way to Canada along the Atlantic coast, with about 2500 people living in it, and at least that many gawping at it at any given time. It’s cuter than a baby trying to eat an apple.

Damariscotta is an Indian name that means something in Indian, I suppose. I don’t speak Abenaki, and neither do Abenakis, so there’s no use askin’, but I think it means: “Place we’ll burn down during King Philip’s War, and again a few times whenever we’re bored and the sheriff’s drunk during the French And Indian Wars.” The colonists got jealous of the Indians getting to burn the place down fortnightly, and burned the place down themselves so the British couldn’t occupy it during the Revolutionary War, or maybe so the bank couldn’t repossess it, I can’t remember, I was very young back then.

[…]

The restaurant was identified to me as haunted, anyway. I was likewise informed that there’s a tour that points out all the local haunted houses, which includes most every building in town but the Rexall. No one ever wants to die and haunt a Rexall. It ain’t dignified. I believe to a certainty that I was supposed to be interested in the fact that the building I was in was haunted by someone besides a man with a liquor license, but I have a defective nature and I wasn’t; but I was fascinated to learn that out-of-plumb doorframes, squirrels in the attic, and a hint of cupidity is enough to get you a paying job lying to people “from away.” And to think I’ve been lying to strangers for free all these years, and on more diverse topics.

There’s an interesting phenomenon I’ve noticed in small cities in the East. The really nice looking cities are made of brick, and all the buildings look like one another, because everything that was there before burned down eleven or four or nine times, until the residents all decided brick buildings were cheaper than a fire department, and built everything at the same time under a regime of architectural and intellectual coherence that is not abroad in the land just now. Damariscotta’s like that; Providence, Rhode Island, parts of Boston, and Portland, Maine are too.

One likewise cannot help but notice that in Damariscotta, the rhythm of the lovely brick buildings, with the occasional gawjus neoclassical residence smattered in, is broken only by the public library, which is fairly new, and built in the Prairie/International/Cow Barn/Reform School style, because reasons. There’s a plaque on the sidewalk that declares the entire downtown a member of the National Register of Historic Places, so you have to check with someone official about the color of the mortar you’re using to fix a brick on your haunted ice cream parlor or haunted Kinko’s or whatever you’ve got, but the town can hire Frank Lloyd Wrong to design the library and place it there like a dead cat at a picnic.

“Innocents Abroad: The Damariscotta Pumpkinfest”, Sippican Cottage, 2013-10-16

June 12, 2013

New disclosure rules for Canadian oil, gas, and mining companies

David Akin in the Toronto Sun:

The Canadian government announced new measures Tuesday that will force oil, gas, and mining companies to publicly disclose every penny they pay to any government at home or around the world.

The move is seen as an anti-corruption measure and one that many activists groups that work in the developing world, such as Oxfam, have been demanding for years, particularly since Canada is home to a majority of the world’s mining companies.

The European Union and the United States have already moved towards mandatory reporting requirements for their mining companies.

There have been cases in some developing countries where multinationals pay a host government substantial sums for the rights to oil, gas or minerals, but the local population complains that they do not know how much their governments are getting and, as a result, cannot demand their governments spend some of that wealth on them.

It’s not just in developing countries, either, as some First Nations activists have complained that they can’t get information on what their band councils receive in various resource development deals here in Canada. Of course, some (many?) deals get done with a bit of bribery to sweeten the attraction, but not every country will have (or enforce) rules like this.

February 11, 2013

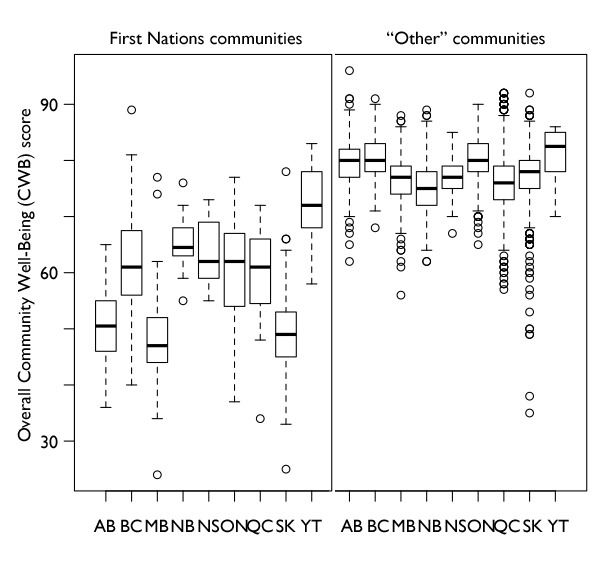

A boxplot of First Nations misery

Over the weekend, Colby Cosh posted this depressing box-and-whisker plot (aka “boxplot”) from statistical data on First Nations communities:

Why did I want to look at this information this way? Because Canada actually performed an inadvertent natural experiment with residential schools: in New Brunswick (and in Prince Edward Island) they did not exist. If the schools had major negative effects on social welfare flowing forward into the future we now inhabit, New Brunswick’s Indians would be expected to do better than those in other provinces. And that does turn out to be the case. You can see that the top three-quarters of New Brunswick Indian communities would all be above the median even in neighbouring Nova Scotia, whose FN communities might otherwise be expected to be quite comparable. (Remember that each community, however large, is just one point in these data. Toronto’s one point, with an index value of 84. So is Kasabonika Lake, estimated 2006 population 680, index value 47.)

On the other hand, and this is exactly the kind of thing boxplots are meant to help one notice, the big between-provinces difference between First Nations communities isn’t the difference between New Brunswick and everybody else. It’s the difference between the Prairie Provinces and everybody else including New Brunswick — to such a degree, in fact, that Canada probably should not be conceptually broken down into “settler” and “aboriginal” tiers, but into three tiers, with prairie Indians enjoying a distinct species of misery. (This shows up in other, less obvious ways in the boxplot diagram. You notice how many lower-side outliers there are in Saskatchewan? That dangling trail of dots turns out to consist of Indian and Métis towns in the province’s north — communities that are significantly or even mostly aboriginal, but that aren’t coded as “FN” in the dataset.)

I fear that the First Nations data for Alberta are of particular note here: on the right half of the diagram we can see that Alberta’s resource wealth (in 2006, remember) helped nudge the province ahead of Saskatchewan and Manitoba in overall social-development measures, but it doesn’t seem to have paid off very well for Indians. This isn’t a surprising outcome, mind you, if you live in Alberta; we have rich Indian bands and plenty of highly visible band-owned businesses, but the universities are not yet full of high-achieving members of those bands, and the downtown shelters in Edmonton, sad to say, still are.

January 25, 2013

Canada and the First Nations — separate nations, separate worlds

In the Globe and Mail, Tom Flanagan explains why the Idle No More protestors insisted on negotiating with the Governor-General:

Actually, native leaders’ focus on the governor-general as the representative of the Crown is based not on a lack of information about the Constitution but on a different understanding of it. They know perfectly well that the prime minister and government of the day are installed by the political process of the nation of Canada, but they don’t see themselves as part of that process and that nation. They see themselves as separate nations, dealing with Canada on a “nation to nation” basis. They see the Crown as a governmental structure above Canada – and therefore the authority with whom they should deal.

Sovereign nations do not legislate for each other; they voluntarily agree to sign treaties after negotiations. The radical conclusion from this premise is that Parliament has no right to legislate for aboriginal people without first getting their consent. Hence the hue and cry about consultation and the demand to repeal those parts of the government’s Budget Implementation acts that allegedly impinge on aboriginal and treaty rights. Today’s claim is that Parliament had no right to amend the Indian Act and the Navigable Waters Protection Act before consulting with (read: getting the approval of) first nations. But the same claim could be made regarding any legislation, for all laws made by Parliament affect native people. Enforcement of the Criminal Code arguably affects aboriginal rights by putting large numbers of aboriginal people in jail, and so on.

This indigenist ideology is not new. It started to appear in the 1970s, as a reaction to Jean Chrétien’s 1969 White Paper, which proposed repealing treaties and abolishing the special legal status of Indians. In its usual well-meaning but sometimes witless way, the Canadian political class thought it could deal with the reaffirmation of indigenism through word magic. Adopt the vocabulary of the radicals. Start calling Indian bands “first nations.” Pretend to recognize their “inherent right of self-government” or even “sovereignty.”

January 19, 2013

Infighting among the factions of the Assembly of First Nations

In the Toronto Star, Tim Harper recounts the behind-the-scenes battles currently going in the Assembly of First Nations:

As he rode to a meeting with Prime Minister Stephen Harper last Friday, Shawn Atleo’s Blackberry buzzed.

“Since you have decided to betray me, all I ask of you now is to help carry my cold dead body off this island,” the text message said.

It was sent in the name of Chief Theresa Spence, but those who saw the text believe it came from someone else in her circle on Victoria Island.

But they were certain about one thing — the timing, moments before he went into one of the most important meetings of his life, was meant to destabilize the National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations and undermine his efforts at a meeting which many in his organization fiercely opposed.

The missive distilled two vicious strains coursing through the internal fighting at the AFN — the threats and intimidation under which its leadership is functioning, and the growing sense from some that the Attawapiskat chief, now entering day 38 of a liquid diet with the temperature dipping to -27C here, is being used as a pawn in an internal political struggle.

To attend last week’s meeting Atleo already had to leave his Ottawa office from a back door to get out of a building with angry chiefs trying to blockade him inside.

He would have to enter the Langevin Block for the meeting through a back door for the same reason.

There have been no shortage of charges, countercharges and denials within the organization over the past weeks and the truth in this saga is often elusive.

January 17, 2013

Ibbitson: First Nations must prioritize political agenda to achieve anything

In the Globe and Mail John Ibbitson lays out the possible and impossible goals and explains why it’s crucial for First Nations to work on the possible goals while there’s still momentum:

In that sense, it might be helpful to look at the disparate demands of the various factions claiming to represent native Canadians living on reserve, in an effort to separate the “deliverables” from the “non-deliverables.”

One key demand is that the Harper government withdraw a raft of legislation, including budget bills that have been passed, that native leaders claim weaken environmental protections and otherwise impair the lives and rights of their people.

Rescinding the budget bills, C-45 and C-38, is 100-per-cent non-deliverable. The Harper government is not going to repeal its budget. No government of any stripe ever would.

But other bills have not been passed. The First Nations Transparency Act, which would require band leaders to publicly report their income, is before the Senate. Native leaders consider its provision onerous and unfair. The Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act aims to improve drinking water safety on reserves, but lacks sufficient funding in the eyes for first nations leaders. It’s still before the Commons. And there are other bills as well.

First Nations leaders would be wise to identify which legislation the Harper government might be convinced to amend, and press for those amendments.

The Assembly of First Nations, in its lists of demands, emphasizes the need for an inquiry into missing and murdered aboriginal women. This is eminently deliverable; native leaders should push hard for it.

Mr. Harper has agreed to take personal charge of negotiations around treaty and land claims. He is known to be personally frustrated with what he sees as an obstructionist bureaucracy at Aboriginal and Northern Affairs. A new and expedited process for resolving claims is deliverable, provided first nations leaders agree in return that resource development is vital to Canada’s and first nations’ economic future.

Any agenda item that requires amending the constitution is completely non-deliverable: after Charlottetown and Meech Lake, Canadians are highly averse to any constitutional tinkering. This limits some aspects of First Nations’ concern, but other areas can and should be addressed. (As pointed out in the article above, revenue sharing from natural resources is a provincial matter, so beating up the feds on that topic is a waste of time and effort.)

Another major factor holding back any chances of meaningful change are the divisions within the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and opposition to the AFN’s leadership from outside the AFN itself. For details, see Terry Glavin’s most recent article in the Ottawa Citizen.