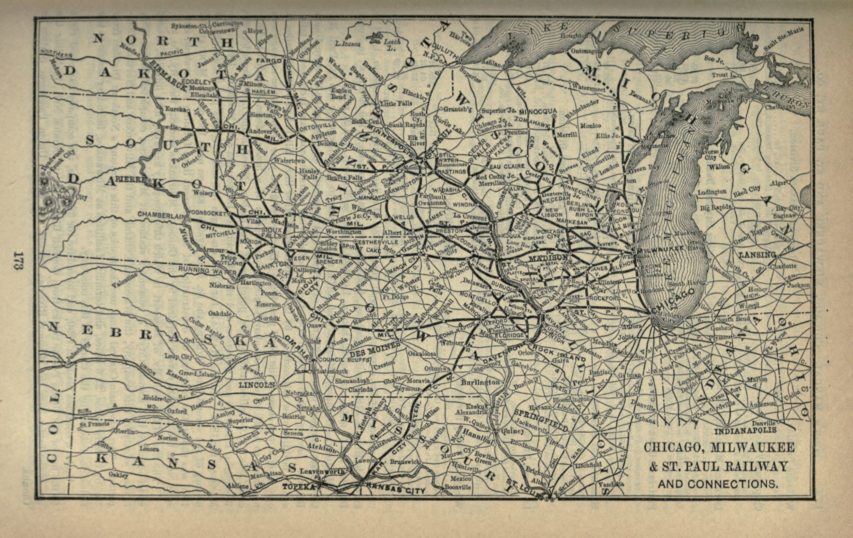

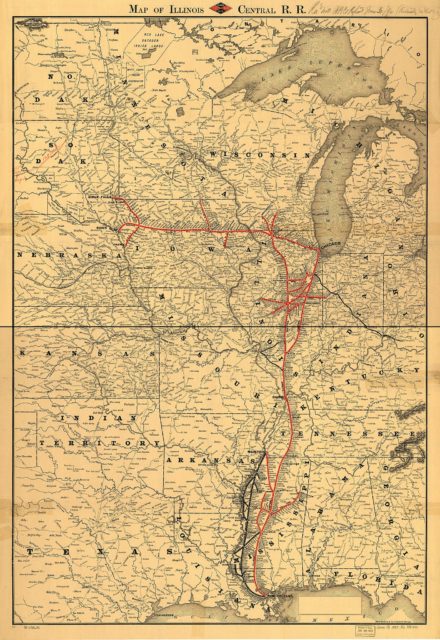

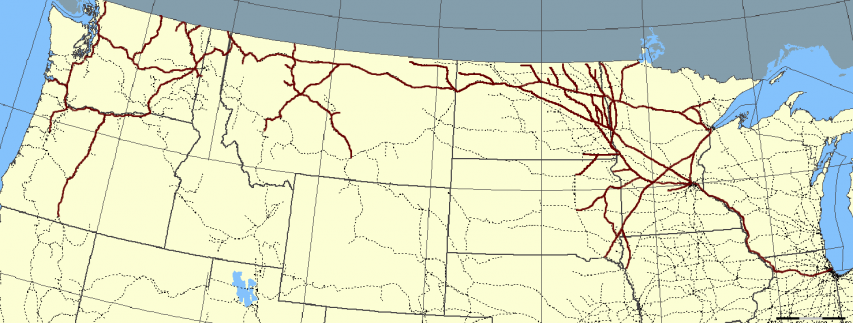

This month’s Classic Trains fallen flag feature is the Chicago Great Western Railroad (CGW) by H. Roger Grant. Not being over-familiar with the US Midwest, while I’d heard of this railway I had no real background knowledge about it. The earliest charter was granted to the Chicago, St. Charles & Mississippi Airline in 1835, but no construction took place under the original management and the charter rights were passed on to the Minnesota and North Western Railroad (M&NW) in 1854. Actual construction of the line did not begin until 1884, connecting St. Paul, Minnesota with Dubuque, Iowa. The M&NW was taken over by the Chicago, St. Paul & Kansas City Railroad under the control of Alpheus Beede Stickney, a St. Paul businessman. By 1892, when the system adopted the Chicago Great Western name, there were routes to Omaha, Nebraska, St. Joseph, Missouri and Chicago.

This month’s Classic Trains fallen flag feature is the Chicago Great Western Railroad (CGW) by H. Roger Grant. Not being over-familiar with the US Midwest, while I’d heard of this railway I had no real background knowledge about it. The earliest charter was granted to the Chicago, St. Charles & Mississippi Airline in 1835, but no construction took place under the original management and the charter rights were passed on to the Minnesota and North Western Railroad (M&NW) in 1854. Actual construction of the line did not begin until 1884, connecting St. Paul, Minnesota with Dubuque, Iowa. The M&NW was taken over by the Chicago, St. Paul & Kansas City Railroad under the control of Alpheus Beede Stickney, a St. Paul businessman. By 1892, when the system adopted the Chicago Great Western name, there were routes to Omaha, Nebraska, St. Joseph, Missouri and Chicago.

The Panic of 1907 ended Stickney’s control of the railway and it ended up in the hands of J.P. Morgan:

Even though Stickney had imaginatively assembled a Midwestern trunk line, he ultimately lost his railroad. The brief but severe Bankers’ Panic of 1907 threw CGW into receivership, a fate the company had avoided during the much more severe Panic of 1893. The nation’s financial wizard, J.P. Morgan, took control, and in 1909 a reorganized Chicago Great Western Railroad made its debut. Morgan wisely placed Samuel Morse Felton in charge, because the new president excelled as a railroad manager. His greatest triumph before joining the Great Western had been to turn the Chicago & Alton into a profitable property.

[…]

The Felton years in Chicago Great Western railroad history resulted in a rehabilitated physical plant. Changes in rolling stock caught the attention of thousands of on-line residents. In 1910, for example, CGW purchased 10 Baldwin 2-6-6-2 Mallets (“Snakes”, as employees called them), and the road’s own shop forces at Oelwein, Iowa, rebuilt three F-3 class 2-6-2s (CGW had 95 total Prairie types) into three more 2-6-6-2s. Unfortunately, these giants did not work out, and in 1916 the Baldwins were sold to the Clinchfield and the homebuilds were rebuilt into 4-6-2s. In the Mallets’ place appeared reliable yet powerful 2-8-2s, of which CGW owned 35.

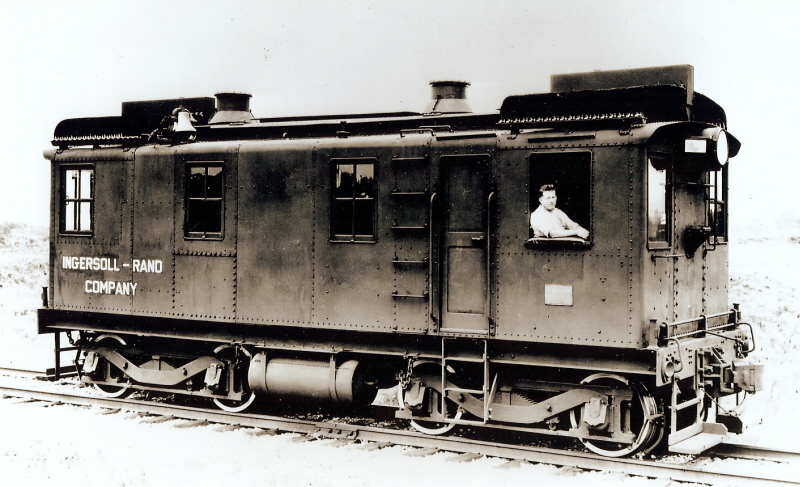

The railroad became a leader in the use of gasoline and later diesel motive power. Before World War I CGW assembled a small fleet of McKeen motor cars, knife-nosed “wind-splitters” that replaced steam-powered branchline and local trains. Its 1924 gas-electric car M-300 was the first unit of any type sold by the Electro-Motive Co., and it helped replace steam on trains 3 and 4 on the 509-mile Chicago–Omaha run. In 1929 CGW remodeled three McKeens to make up a deluxe gas-electric train, the Minneapolis–Rochester (Minn.) Blue Bird. CGW was mostly satisfied with its pioneering internal-combustion equipment.

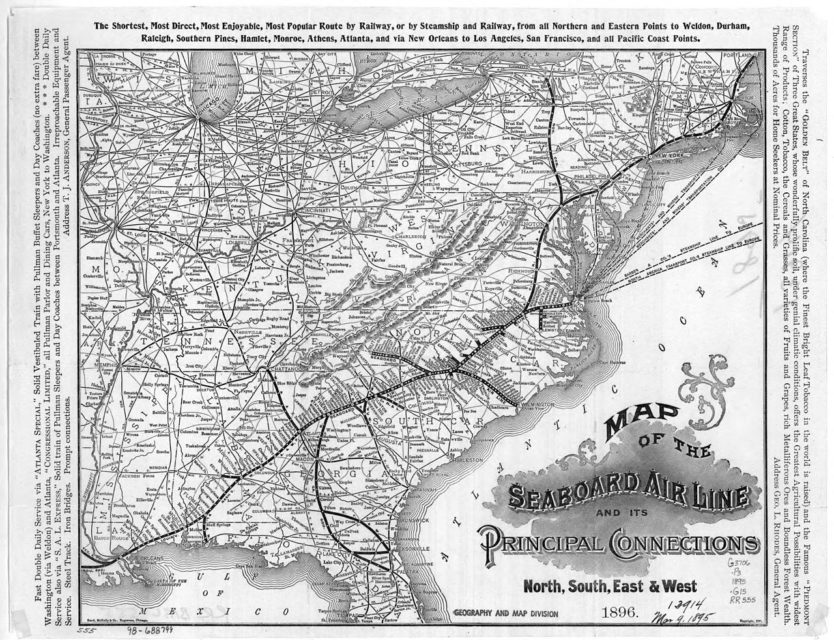

1906 advertising blotter for the Chicago Great Western Railroad’s passenger trains.

Wikimedia Commons.

CGW’s independent life came to an end in the same era as a lot of small to medium sized railways disappeared into corporate mergers, take-overs, or bankruptcy:

Being a small road in an era when competitors were expanding through mergers led to the corporate demise of the CGW. Saying that shareholders “must be protected”, the board sought a partner. Although the expectation was union with KCS or perhaps the Soo Line, the aggressive Chicago & North Western, headed by resourceful Ben W. Heineman, made an acceptable proposal, and in 1968 Chicago Great Western Railroad history ended with it becoming a Fallen Flag.

C&NW operated CGW switchers and F units for a short time, and assimilated Great Western’s only second generation diesels — eight GP30s and nine SD40s, all painted in the final solid “Deramus red” seen also on KCS and Katy — into the yellow fleet.

Although for a short time much of the former Great Western maintained its identity as C&NW’s Missouri Division, that operating organization ended and its lines started to disappear. By the 1980s much of the trackage had been retired, and at the start of the 21st century only about 145 miles remained. Survivors include portions of the main lines in Iowa (Mason City to the Fort Dodge area; Oelwein–Waterloo; and a leg into Council Bluffs); the Cannon Falls (Minn.) branch; and terminal trackage around South St. Paul, Minn., and just west of Chicago.