Epimetheus

Published 8 Oct 2019Rise and Fall of the Sikh Empire explained in less than 7 minutes Sikh history documentary

This video covers Sikh history from the Guru Nanak till the fall of the Sikh Empire.

This video and others like it are sponsored by my Patrons over on patreon.

https://www.patreon.com/Epimetheus1776

June 1, 2021

Rise and Fall of the Sikh Empire explained in less than 7 minutes

October 10, 2020

China’s national memories are oddly inconsistent

At UnHerd, Bill Hayton looks at the one conflict between China and a western nation that bulks disproportionally large in the current Chinese government’s historical grievance-bank:

“The 98th Regiment of Foot at the attack on Chin-Kiang-Foo, 21 July 1842.”

Painting by Richard Simkin (1840-1926) via Wikimedia Commons.

Take three mid-19th century Asian conflicts: one killed 20 million people, one killed well over 100,000 and a third killed 20,000. Which one, despite being barely noticed by the Chinese government at the time, is the most discussed today and has become emblematic of an historic clash between East and West?

The immensely deadly Taiping Rebellion between 1850 and 1864 and the vicious conflict between “Hakka” and “Cantonese” peoples between 1855 and 1867 are barely known outside China, despite their far bloodier impacts on human lives. We know vastly more about the “First Opium War” of 1840 because it has played a totemic role in two political arenas: one in China and one in the UK. And in both places, the origins of the war have been obscured and distorted to suit political agendas.

In China, the “Opium War” marks the beginning of what the Communist Party currently calls the “century of national humiliation” — a period of unrelenting misery that only ended in 1949 with the Party’s victory in the Chinese Civil War. It is a narrative that underpins both the Party’s right to rule China and its increasingly assertive foreign policy. In Britain, the narrative of the war has been a weapon wielded variously by Liberal critics of a Whig government, puritan campaigners against drugs, leftist opponents of British foreign policy and Twitter-users claiming that white people are inherently racist. All these critiques and narratives caricature the evidence.

In the comic-book version, the British Empire went to war in 1840 to force an illegal and immoral drug, opium, down the respiratory passages of the Chinese people, purely for its own ill-gotten ends. This narrative is oddly patronising. It assumes that the Chinese side were merely naïve dupes, hapless victims to imperial power. It is time to recognise that there were several protagonists in the First Opium War.

On one side were the British free-traders, men who wanted an end to Chinese restrictions on commerce, whether of cotton or opium. There was also an East India Company anxious to maintain its good relations with local officials, and a London government and its critics with their own agendas. On the other was an imperial court in Beijing split between reformers and a clique of Chinese conservative “scholar-officials” intent on keeping foreign influence at bay. In the middle was an Asian financial problem triggered by a European war.

July 15, 2020

When The Dutch Ruled The World: Rise and Fall of the Dutch East India Company

Business Casual

Published 14 Sep 2018Thanks to Cheddar for sponsoring this episode! Check out their video on the iconic ad campaign that saved Old Spice here: https://chdr.tv/youtu8b4a6

⭑ Subscribe to Business Casual → http://gobc.tv/sub

⭑ Enjoyed the vid? Hit the like button!Follow us on:

► Twitter → http://gobc.tv/twtr

► Instagram → https://gobc.tv/ig

► LinkedIn → https://gobc.tv/linkedin

► Reddit → https://gobc.tv/reddit

► Medium → https://gobc.tv/medium

July 5, 2020

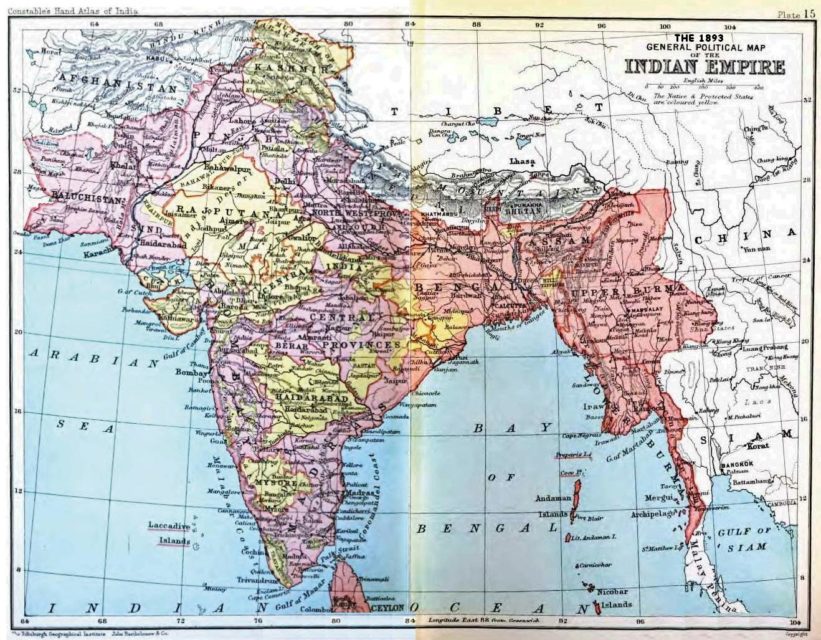

History Summarized: Colonial India

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 4 Jul 2020Start your free trial at http://squarespace.com/overlysarcastic and use code

OVERLYSARCASTICto get 10% off your first purchase.Indian History has always been a story of peoples coming and going, but the subcontinent’s modern history takes that up to 11, with the arrival of Central Asian Mughals and boatloads of Europeans. See how India transforms from Medieval to Modern in this final act of our History of India.

SOURCES & Further Reading: The Discovery of India by Jawaharlal Nehru, A History of India by Michael H. Fisher (a lecture series by The Great Courses).

This video was edited by Sophia Ricciardi AKA “Indigo”. https://www.sophiakricci.com/

Our content is intended for teenage audiences and up.Special thanks to Varda Alighieri for coaching me through my (hopefully serviceable) pronunciations!

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

MERCH LINKS: https://www.redbubble.com/people/OSPY…

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

June 19, 2020

Anglo-Dutch Wars | 3 Minute History

Jabzy

Published 25 Apr 2015First, Second and Third Anglo-Dutch Wars. I left out the Fourth War because it really wasn’t connected to the previous 3.

Also – I hope you don’t mind I used ‘Netherlands’ throughout the video despite the fact the term didn’t come until much later.

April 16, 2020

Prologue: The Dutch Colonial Whip | The Indonesian War Of Independence

TimeGhost History

Published 15 Apr 2020This is the prologue to our five-part Indonesian War of Independence Miniseries. It sets the stage of brutal colonial repression, a growing sense of Indonesian Nationalism and ultimately the desire to be free.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by:

Spartacus Olsson and Joram Appel

Directed by: Astrid Deinhard

Produced by: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Joram Appel and Isabel Wilson

Edited by: Wieke Kapteijns, Guido Becker

Sound design: Marek KamińskiColorizations by: Dememorabilia – https://www.instagram.com/dememorabilia/

Research Sources: https://bit.ly/IndoSources

Visual Sources:

Tropenmuseum, part of the National Museum of World Cultures

Wellcome ImagesIcons retrieved via The Nounproject: gold by Phạm Thanh Lộc, slaves by Salaidinovich, silver by Marie Van den Broeck, spice by ahmad, Opium Poppies by Matt Wasser.

Music:

“Disciples of Sun Tzu” – Christian Andersen

“Weapon of Choice” – Fabien Tell

“Guilty Shadows 4” – Andreas Jamsheree

“Road To Tibet 5” – Rannar Sillard

“Sailing for Gold” – Howard Harper-Barnes

“The Inspector 4” – Johannes Bornlöf

“The Dominion” – Bonnie Grace

“Heroes On Horses” – Gunnar Johnsén

“Not Safe Yet” – Gunnar JohnsenA TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

TimeGhost History

2 days ago (edited)

This is the prologue to our new ‘Indonesian War of Independence’ mini-series. Now, we initially only wanted to do five episodes, but episode one became double as long as we imagined, so we decided to cut the historical context out and put it in a prologue. These series are mainly written by Joram and Isabel, two historians from the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Now, you might say that we are not in the best position to talk about European Imperialism because of that. However, as we’re both academically trained historians, we believe that we’re able to overcome any bias through the use of academic methods and peer-reviewed academic sources. If anyone is interested to take a look at our source-list, you can find it right here: https://bit.ly/IndoSourcesThese mini-series have been chosen out of a bigger selection by our TimeGhost Army. They fund almost our entire production – this would not exist without them. Become one of them to choose future series and to support the creation of content just like this! You can do that at patreon.com/timeghosthistory or https://timeghost.tv.

Cheers,

Joram

January 20, 2020

Gaming India’s colonial and post-colonial history

In Quillette, Jonathan Kay looks at two wargames that deal with different aspects of Indian history:

… the peoples whom Europeans encountered in the Americas were skilled and inventive combatants who often put white men to flight (or worse) despite their enormous disadvantage in technology and (ultimately) manpower. In many cases, First Nations (as we now call them in Canada) fought fiercely with one another, too, and had well-developed military traditions that Europeans variously feared, admired and adopted. And they would make fitting protagonists for any modern boardgame designer willing to reject the current fashion of presenting indigenous peoples as holy elves of the forest.

What would such a game look like? A good example comes to us in the form of GMT Games’ 2019 release, Gandhi: The Decolonization of British India. This is the latest entry in GMT’s COIN series, which is designed to model guerrilla wars and other unconventional conflicts through the use of cards that represent historical events. As in other games of the genre, such as Fire in the Lake (Vietnam), People Power (Insurgency in the Philippines, 1983-1986) and Colonial Twilight (The French-Algerian War, 1954-62), the game doesn’t present a simple narrative of good versus evil, but a more complex narrative in which all sides have at least some ulterior motives that are at odds with their official propaganda. In Gandhi, there are four players, one each controlling the Raj, the Indian National Congress, the Muslim League and the “Revolutionaries.” The latter three all share the goal of some kind of national independence, but each pursues its own (often mutually antagonistic) methods, with the Revolutionaries using violence to undercut the more pacifistic Congress, and the Muslim League playing off Congress, the Revolutionaries and the Raj in order to protect the interests of the country’s Islamic minority. (Historians of Canada would note that diplomacy and warfare with and among First Nations often was similarly complex.)

The game is unpredictable and complex, since each player will pursue different strategies in the country’s many different zones, making and breaking de facto partnerships depending on the circumstances. Amid all of this gaming chaos, the moral logic of decolonization remains a central theme of the game. But by the end of things, you realize that the ejection of the British from India was a big and messy project, as history typically is. While Spirit Island was created with the goal of mainlining anti-colonialism directly into the boardgame experience, Gandhi gets to the same theme obliquely by way of amoral realism, doing a better job pedagogically in the process.

A key aspect of Gandhi is that the Raj has agency: It is not reduced to the status of automaton-villain, as in Spirit Island. But there are limitations to the imaginative ecosystem that players inhabit: Every one of the four players has to take on their assigned role without questioning their underlying, game-dictated objective — including the Raj player, who must, start to finish, exert himself in defence of a colonial project that now is widely viewed as being on the wrong side of history. The other three factions likewise remain prisoners of their parochial regional, religious and doctrinal differences, which, historically, would contribute to millions of deaths in the chaos that accompanied the British exit.

Which brings me to the fourth and final colonialism-themed game I will discuss: the acclaimed 2017 release John Company, by Indiana-based designer Cole Wehrle. In theory, John Company is also a game about British colonialism in India. But here’s the rub: The players all act as competing factions within the commercial innards of John Company (a nickname for the British East India Company). On one hand, the players have a co-operative goal — to keep the company afloat as it manages the enormous expense of creating and operating a colonial apparatus on the subcontinent. But I can attest that far more of players’ mental energy goes into fighting each other for the spoils of war and trade. Indeed, much of the game consists of exchanging favours and bribes among players, as each attempts to leverage positions of power within the company to extract revenues, plunder and positions of influence.

As the game progresses, you notice, almost as an afterthought, that great things are afoot within India: New trade routes are created, military battles are fought, whole regions go into revolt and are pacified, with many (fictional) lives hanging in the balance. But as a player, you barely notice any of this — except to the narrow extent these events can be exploited as a source of wealth, since the way you win the game is by accumulating enough cash and baubles to retire your functionaries into gilded clubs and country houses back in England.

And what of the actual Indians who lived and died under the Raj? They don’t appear at all in the game, for John Company‘s real play arc exists within the corrupt solipsism of intra-corporate deal-making. Which sounds horrifyingly amoral. But when the game’s over, you realize: That’s the whole point. The colonialists who ran India — like those who came to North America and every other place on the map, from South America to the Belgian Congo to China — typically weren’t motivated by a desire to destroy and subjugate. They were out to make a buck, either as lone freelancers in a canoe, or bureaucrats pulling levers within some gigantic corporate behemoth. The horrifying, often genocidal murder and mayhem was a by-product of greed. Which doesn’t make it better. But it does make the narrative more comprehensible in regard to governing our future behaviour as human societies — since we all are vulnerable to spasms of greed, while true evil for its own sake is a rare thing.

Games teach you about the forces of history not by listing a set of facts for you to memorize, but by creating a rules system that effectively pushes you to act in a certain way — whether as a colonialist, revolutionary or deity. If the game is well-designed, then those actions make a certain kind of internal sense. That dark logic is what stays with you — as an explanation of why people acted a certain way at a certain time. It’s always easy to judge historical figures. It’s harder, but ultimately more interesting and valuable, to understand them.

February 13, 2019

The origins of the word “loot”

William Dalrymple wrote about the Honourable East India Company for the Guardian a few years back, including the way the word “loot” entered common English usage:

The Mughal emperor Shah Alam hands a scroll to Robert Clive, the governor of Bengal, which transferred tax collecting rights in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa to the East India Company, August 1765.

Oil painting by Benjamin West (1738-1820) via Wikimedia Commons.

One of the very first Indian words to enter the English language was the Hindustani slang for plunder: “loot”. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this word was rarely heard outside the plains of north India until the late 18th century, when it suddenly became a common term across Britain. To understand how and why it took root and flourished in so distant a landscape, one need only visit Powis Castle.

The last hereditary Welsh prince, Owain Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn, built Powis castle as a craggy fort in the 13th century; the estate was his reward for abandoning Wales to the rule of the English monarchy. But its most spectacular treasures date from a much later period of English conquest and appropriation: Powis is simply awash with loot from India, room after room of imperial plunder, extracted by the East India Company in the 18th century.

There are more Mughal artefacts stacked in this private house in the Welsh countryside than are on display at any one place in India – even the National Museum in Delhi. The riches include hookahs of burnished gold inlaid with empurpled ebony; superbly inscribed spinels and jewelled daggers; gleaming rubies the colour of pigeon’s blood and scatterings of lizard-green emeralds. There are talwars set with yellow topaz, ornaments of jade and ivory; silken hangings, statues of Hindu gods and coats of elephant armour.

Such is the dazzle of these treasures that, as a visitor last summer, I nearly missed the huge framed canvas that explains how they came to be here. The picture hangs in the shadows at the top of a dark, oak-panelled staircase. It is not a masterpiece, but it does repay close study. An effete Indian prince, wearing cloth of gold, sits high on his throne under a silken canopy. On his left stand scimitar and spear carrying officers from his own army; to his right, a group of powdered and periwigged Georgian gentlemen. The prince is eagerly thrusting a scroll into the hands of a statesmanlike, slightly overweight Englishman in a red frock coat.

The painting shows a scene from August 1765, when the young Mughal emperor Shah Alam, exiled from Delhi and defeated by East India Company troops, was forced into what we would now call an act of involuntary privatisation. The scroll is an order to dismiss his own Mughal revenue officials in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, and replace them with a set of English traders appointed by Robert Clive – the new governor of Bengal – and the directors of the EIC, who the document describes as “the high and mighty, the noblest of exalted nobles, the chief of illustrious warriors, our faithful servants and sincere well-wishers, worthy of our royal favours, the English Company”. The collecting of Mughal taxes was henceforth subcontracted to a powerful multinational corporation – whose revenue-collecting operations were protected by its own private army.

It was at this moment that the East India Company (EIC) ceased to be a conventional corporation, trading and silks and spices, and became something much more unusual. Within a few years, 250 company clerks backed by the military force of 20,000 locally recruited Indian soldiers had become the effective rulers of Bengal. An international corporation was transforming itself into an aggressive colonial power.

Using its rapidly growing security force – its army had grown to 260,000 men by 1803 – it swiftly subdued and seized an entire subcontinent. Astonishingly, this took less than half a century. The first serious territorial conquests began in Bengal in 1756; 47 years later, the company’s reach extended as far north as the Mughal capital of Delhi, and almost all of India south of that city was by then effectively ruled from a boardroom in the City of London. “What honour is left to us?” asked a Mughal official named Narayan Singh, shortly after 1765, “when we have to take orders from a handful of traders who have not yet learned to wash their bottoms?”

January 7, 2019

The Private Army of the British East India Company

Brandon F.

Published on 15 Dec 2018Before the days of the Raj, British India was ruled by a private corporation: The Honourable East India Company. The Company, which began in India as a purely mercantile institution, eventually came to control vast territories across the subcontinent. These wild frontiers and busy cities required garrisons to defend them, and the expansion of Company interests demanded the ability to wage war. To do this, the Company commanded a massive private army. Made up of both European and Indian soldiers, and working in close — if not always frictionless — tandem with H.M.’s regiments, it was a fascinating institution that only came to an end with the massive Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 and the dissolution of Company rule.

In this video, I discuss the organization of this army, and the way in which it related to government forces.

If you would like to support the Channel on Patreon:

https://www.patreon.com/BrandonF

August 31, 2018

How did Britain Conquer India? | Animated History

The Armchair Historian

Published on 10 Aug 2018Check out History With Hilbert: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hs1sw…

Our Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/armchairhistory

Our Twitter: https://twitter.com/ArmchairHist

Sources:

https://dailyhistory.org/Why_was_Brit…

1857 Indian War of Independence: 1857 Indian Sepoys’ Mutiny, Shahid Hussain Raja

The East India Company, Brian Gardner

The Corporation that Changed the World: How the East India Company Shaped the Modern Multinational, Nick Robins

A History of India, Peter Robb

May 22, 2018

Feature History – Opium Wars

Feature History

Published on 19 Oct 2016Welcome to Feature History, featuring the Opium Wars, western imperialism, and this fancy new intro and vignette.

The super sexy stuff like animation, voice, and script are all by the super sexy me.

The music is Anamalie and Clash Defiant, both by Kevin MacLeod

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Feature_History

July 30, 2017

“… sooner or later, and usually sooner, the British will be blamed”

In Pragati, Alex Tabarrok reviews Shashi Tharoor’s 2016 book history of the British Raj, An Era Of Darkness:

At sophisticated dinner parties in Delhi, Calcutta, or Chennai, whenever the discussion turns to politics, one can be sure that sooner or later, and usually sooner, the British will be blamed. It’s a fine parlor game, and clever players can usually find a way to cast blame for whichever side of the debate they favor. Is India’s traditional family falling apart due to internet porn? Blame the British! Are the laws against homosexuality too strong? Blame the British! The British are an easy target because much of what they did was reprehensible. But blaming British imperialism for contemporary Indian problems is also an easy way to let India’s political class off the hook.

An excellent case against the British comes from Shashi Tharoor, bestselling author, former Under-Secretary-General at the United Nations, and current member of the Indian parliament, in his 2016 book An Era of Darkness: The British Empire in India (also published this year under the title Inglorious Empire[UK title]).

Tharoor makes three claims:

- The British empire in India, from the seizure of Bengal by the East India Company in 1757 until the end of British government rule in 1947, was cruel, rapacious, and racist.

- India would be much better off today had it not been for British rule.

- Britain’s success and the Industrial Revolution were due to British depredation of India.

The first claim is true, the second uncertain, the third false.

The first claim is the heart of Tharoor’s book: the British empire in India was cruel, rapacious and racist. All true. But who would expect otherwise? Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. The theft, the famines, the massacres, the formal and casual racism, the utter hypocrisy of suppressing independence while using hundreds of thousands of Indian soldiers to fight for democracy and freedom in two World Wars — on all this Tharoor stands on solid ground. The ground is solid in part because it has been well-trod. Tharoor brings the case against the East India Company and Britain, initiated by Edmund Burke (1774-1785) and continued by the likes of Indian nationalist Dadabhai Naoroji [PDF] (1901) and American historian Will Durant (1930), to its conclusion and climax with the Indian independence movement. In this, Tharoor is entirely successful and his work deserves to be widely read.

In his eagerness to blame Britain, however, Tharoor reaches for every possible argument in ways that are sometimes misleading and sometimes absurd.

February 26, 2017

British History’s Biggest Fibs with Lucy Worsley Episode 3: The Jewel in the Crown

Published on 10 Feb 2017

In the final episode, Lucy debunks the fibs that surround the ‘jewel in the crown’ of the British Empire – India. Travelling to Kolkata, she investigates how the Raj was created following a British government coup in 1858. After snatching control from the discredited East India Company, the new regime presented itself as a new kind of caring, sharing imperialism with Queen Victoria as its maternal Empress.

Tyranny, greed and exploitation were to be things of the past. From the ‘black hole of Calcutta’ to the Indian ‘mutiny’, from East India Company governance to crown rule, and from Queen Victoria to Empress of India, Lucy reveals how this chapter of British history is another carefully edited narrative that’s full of fibs.

July 11, 2016

First Opium War – II: The Righteous Minister – Extra History

Published on 25 Jun 2016

Opium was illegal in China, but that didn’t stop the East India Company from manufacturing it for the black market. The Chinese emperor appointed an official, Lin Zexu, to stop it. He seized and burned huge opium caches held by British merchants, and ultimately ordered the British out of China entirely. Instead, they set up base on a barren island that would become known as Hong Kong.

____________The tea trade flowing from China had left the British government in staggering debt. They had loaned huge amounts to the Honourable East India Company (EIC) to conquer India, and to pay their debts, the EIC turned that land into poppy fields and manufactured opium in huge quantities. Since China had banned the opium trade, the EIC set up a market in Calcutta (part of their Indian territory) and turned a blind eye to the black market traders who smuggled it into China. By 1839, over 6.6 million pounds of opium were being smuggled into China every year. The Chinese DaoGuang Emperor appointed an upright official named Lin Zexu to halt this opium trade. Lin orchestrated a massive campaign to arrest opium traders, force addicts into rehab, and confiscate pipes. He even laid siege to British warehouses when the merchants refused to turn over their opium supply, instead taking it all by force and burning it. The outraged merchants sought redress from their government, but although the Chief Superintendant Charles Elliot promised them restitution, the government never had any intention of paying them back. Amid the unrest, two British sailors brutally murdered a Chinese man. Lin Zexu demanded their extradition, but Elliot insisted on trying them aboard his ship and sentencing them himself. Lin Zexu had enough. He halted the British food supply and ordered the Portuguese to eject them from Macau. They retreated to a barren island off the coast (now known as Hong Kong). Since the island could not support them, Elliot petitioned the Chinese to sell them food again. He received no response. Then he sent men to collect it directly, but on their way back they were halted by the Chinese navy, and the first engagement of the Opium Wars began.

June 3, 2015

Re-examining the history of “the Raj”

In The Diplomat, Nigel Collett reviews a new book by Ferdinand Mount called The Tears of the Rajas: Mutiny, Money and Marriage in India 1805-1905:

It was the discovery of a book by his aunt, Ursula Low, published in 1936 and entitled Fifty Years with John Company, which opened Mount’s eyes to his family’s history and led to the writing of The Tears of the Rajas.

His aunt’s book, a work long ignored and derided as an eccentricity by her family, was a biography of her grandfather, General Sir John Low. What staggered Mount about his aunt’s account was her matter-of-fact recording of the massacres, mutinies and mayhem in which her grandfather and many of her relatives had been involved during their colonial careers. For General Sir John Low had, during a career in India that lasted from 1804 to 1858, seen the brutal suppression of the mutiny of his own regiment at Vellore a year after his arrival in India, the “White Mutiny” of European soldiers in the East India Company’s Forces in 1808 (which resulted in the massacre not of the European mutineers but of the Indian soldiers they led) and finally, in 1857, of the Indian Mutiny itself, which erupted at a time when Low was the Military Member of the Governor General’s Council.

More than this, Low, in a largely political career up until the outbreak of the Mutiny, had been intimately involved in policies which led directly to it, including the removal from power of three Indian potentates to whom he was attached as Resident (the Peshwa of Poona, the Raja of Nagpur and the King of Oudh) and the annexation of their lands. He was at one point, in yet another posting as Resident, personally involved in detaching a large chunk of Hyderabad from the lands of the Nizam.

During his service, Low had watched, and other members of his family had been involved in, the British annexations of Sind and the Punjab, the conquest of Gwalior and the disastrous attempt to depose Dost Mohammed, the Shah of Afghanistan, which led to the catastrophe of the 1st Afghan War. Mount’s title is well chosen: Low literally reduced several of his Rajas to tears.

[…]

Perhaps more stomach-turning than this, especially to a British reader, are Mount’s revelations of the dishonest policies followed by almost every Governor General of India towards India’s native princes, policies driven by pure greed, conducted with cold ruthlessness in utter disregard of treaties, promises or any code of honor, and hidden beneath layers of hypocritical cant. Much of this has not been made generally known. Few, for instance, in the Far East, will know that as the First Opium War in China ended in 1842, another began in India, for the British conquest of Gwalior was aimed at the control of the opium it grew independently of the East India Company.

The removal of misgovernment was all too frequently the fraudulent public excuse for the imposition of direct rule and the canard of the protection of the peasantry from their own rulers was little more than a front for taxing them more efficiently. Add to this noxious behavior insulting racial pride, ignorance of culture and tradition, and a religious evangelism that persuaded army officers that it made sense to tell their Hindu and Muslim soldiers that they would go to Hell if the wars into which they were leading them resulted in their unconverted deaths, and there seems little need for further explanation of why it all ended in disaster in 1857.

While I can’t claim to have read deeply in Indian history during this period, I still think the best introduction to the at-best-ambivalent legacy of British rule is the fictional exploits of Sir Harry Flashman by George MacDonald Fraser (especially the original Flashman, Flashman and the Mountain of Light, and Flashman in the Great Game). How many other novels have extensive footnotes about all the historical characters and situations the fictional hero encounters? Oh, right … for the younger set: trigger warning in all the Flashman novels for racism, sexism, imperialism, militarism, violence, and pretty much anything that would offend the ears of a young Victorian lady modern university student.