Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published on 30 Aug 2019Check out the Armchair Historian channel for more on French Vietnam and the battle of Dien Bien Phu: https://youtu.be/IJ051WyUsW8

Dubious morality, drawn out timescales, intricate royal politics, worldwide stages — Colonialism be like that sometimes. And by “Like That” I mean impenetrably complicated. I did my best, I’ll say that, but oh man is history a mess in the 15-1900s. This stuff is the reason I had so much trouble with history for so long. It’s just so DENSE.

ANYWAY, join Blue and Griffin the Armchair Historian for a look into the history of the multiple successive French Empires. Listen carefully as Blue makes imperceptibly subtle commentary about his extremely non-biased opinions on this chapter in history, and laugh together as we analyze the historical significance of Napoleon Bonaparte’s anime hair.

NOTE on 6:14 — I say Napoleon became Emperor in 1802. That’s a mistake. In 1802, the constitution of France was amended to make the position of Consul permanent, but Napoleon did not become the Emperor until 1804, when he declared the French Empire. That’s my bad.

NOTE on 11:25 — French Guiana, on the northeast coast of South America, remained part of France following the decolonization of Africa. That’s a mapping mix-up.

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/sS5K4R3

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

August 31, 2019

History Summarized: French Empire (Ft. Armchair Historian!)

August 28, 2019

And then came Genghis Khan – Sorrow of the Song Dynasty l HISTORY OF CHINA

IT’S HISTORY

Published on 10 Aug 2015The Song dynasty is often described as an early modern economy. It marked a lot of economical changes from previous dynasties. Starting with the decentralisation of power and reduced economical involvement, it brought on industrial growth and agricultural expansion. Although being forced to advance in military technology due to wars with the Liao and the Jurchen, the Song would eventually fall to the Mongols. Crumbling under Genghis Khan’s attacks it would only take one generation until his successor Kublai Khan would declare a new Yuan Dynasty. Find out all about this Epoch on IT’S HISTORY!

» SOURCES

Videos: British Pathé (https://www.youtube.com/user/britishp…)

Pictures: mainly Picture Alliance

Content:

Benn, Charles (2002), China’s Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang dynasty, Oxford University Press

Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Gascoigne, Bamber; Gascoigne, Christina (2003), The Dynasties of China: A History, New York

Levathes, Louise (1994), When China Ruled the Seas, New York: Simon & Schuster

Whitfield, Susan (2004), The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith, Chicago: Serindia» ABOUT US

IT’S HISTORY is a ride through history – Join us discovering the world’s most important eras in IN TIME, BIOGRAPHIES of the GREATEST MINDS and the most important INVENTIONS.» HOW CAN I SUPPORT YOUR CHANNEL?

You can support us by sharing our videos with your friends and spreading the word about our work.» CAN I EMBED YOUR VIDEOS ON MY WEBSITE?

Of course, you can embed our videos on your website. We are happy if you show our channel to your friends, fellow students, classmates, professors, teachers or neighbors. Or just share our videos on Facebook, Twitter, Reddit etc. Subscribe to our channel and like our videos with a thumbs up.» CAN I SHOW YOUR VIDEOS IN CLASS?

Of course! Tell your teachers or professors about our channel and our videos. We’re happy if we can contribute with our videos.» CREDITS

Presented by: Guy Kiddey

Script by: Guy Kiddey

Directed by: Daniel Czepelczauer

Director of Photography: Markus Kretzschmar

Music: Markus Kretzschmar

Sound Design: Bojan Novic

Editing: Markus KretzschmarA Mediakraft Networks original channel

Based on a concept by Florian Wittig and Daniel Czepelczauer

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard-Olsson, Spartacus Olsson

Head of Production: Michael Wendt

Producer: Daniel Czepelczauer

Social Media Manager: Laura Pagan and Florian WittigContains material licensed from British Pathé

All rights reserved – © Mediakraft Networks GmbH, 2015

August 24, 2019

Italy’s African Destiny | BETWEEN 2 WARS I 1931 Part 1 of 3

TimeGhost History

Published on 23 Aug 2019When Mussolini wants to solidify Italy’s North African colonies, he faces massive opposition by one man: Omar Mukhtar, the Lion of the Desert.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Subscribe to our World War Two series: https://www.youtube.com/c/worldwartwo…

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Spartacus Olsson

Directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Naman Habtom

Edited by: Daniel Weiss

Sound design: Iryna DulkaArchive by Reuters/Screenocean http://screenocean.com

Sources:

Online:

https://www.politico.com/blogs/ben-sm…

Muslim Fascist Party and Youth Wing

http://countrystudies.us/libya/21.htm (Library of Congress)

https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/senussi…

https://awayfromthewesternfront.org/c…

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-…

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/ar…Journal Articles:

Arielli, Nir. “Italian Involvement in the Arab Revolt in Palestine, 1936-1939.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 35, no. 2, 2008, pp. 187–204. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20455584.Bussotti, L. (2016) “A History of Italian Citizenship Laws during the Era of the Monarchy (1861-1946)”. Advances in Historical Studies, 5, 143-167. doi: 10.4236/ahs.2016.54014.

Cooke, James J. “Destino Affricano De Popolo Italiano: Franco-Italian Controversy Over Tunisia, 1936-1940.” Proceedings of the Meeting of the French Colonial Historical Society, 13/14, 1990, pp. 203–216. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42952205.

Collins, Carole. “Imperialism and Revolution in Libya.” MERIP Reports, no. 27, 1974, pp. 3–22. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3011335.

KOPANSKI, ATAULLAH BOGDAN. “ISLAM IN ITALY AND IN ITS LIBYAN COLONY (720-1992).” Islamic Studies, vol. 32, no. 2, 1993, pp. 191–204. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20840121.

Pankhurst, Richard. “Education in Ethiopia during the Italian Fascist Occupation (1936-1941).” The International Journal of African Historical Studies, vol. 5, no. 3, 1972, pp. 361–396. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/217091.

Pretelli, Matteo. “Education in the Italian colonies during the interwar period.” Modern Italy, Vol. 16, No. 3, August 2011, 275–293

Books:

Mark I. Choate: Emigrant nation: the making of Italy abroad, Harvard University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-674-02784-1, page 175.Peter Bandella The Eternal City: Roman Images in the Modern World, Chapter 7 – The University of North Carolina Press, 1987, ISBN 0-8078-6511-7

Ahmad Hassanein Bey The Lost Oases (read a Swedish translation by Ulla Ericson), American University of Cairo, reprinted 2006 (original 1925), ISBN 978-91-87771-41-5

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

TimeGhost History

1 hour ago

As we approach one year of WW2 In Real Time we cannot express our gratitude for your support enough. It is the financial and spiritual involvement of the TimeGhost Army at https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory and https://timeghost.tv that has made it possible for us to do all of this – so thank you, once again!This episode comes out as our WW2 series is covering the first battles in the North African theatre. The Second World War there will have major impact on world events between 1940 and 1944. And this is the second episode covering the background to the conflict in North Africa and the Middle East. We will return to Africa again, but before that we will look at what is going on in Germany, Japan and the USSR in the early 1930s – as some of you might already guess or know, those are dramatic times in those places and it is in these years that the world takes its first concrete steps towards the conflict that erupts into world war in 1939.

August 17, 2019

The British Empire in retrospect

It’s been fashionable to dismiss the British Empire as a positive force in history for about 100 years (partly in reaction to the losses during the First World War), but Casey Chalk reviews a recent book that counter-cherry-picks the facts to show it wasn’t all an authoritarian dystopia and cultural wasteland:

… the central argument of University of Exeter professor of history Jeremy Black’s new book Imperial Legacies: The British Empire Around the World, which, according to the book jacket, is a “wide-ranging and vigorous assault on political correctness, its language, misuse of the past, and grasping of both present and future.” The imperial legacy of Great Britain is also, in a way, an instructional lesson for the United States, which, much like the British Empire of the early to mid-20th century, is experiencing a slow decline in influence.

As a former history teacher who has visited many former British colonies in Africa and Asia, I’ve been well catechized in how British imperialism is interpreted. The British, so we are told, were violent aggressors and expert political manipulators. Using their technological superiority and command of the seas, they subjugated cultures across the globe, applied the “divide and rule” policy to set ethnic and linguistic groups against one another, extracted resources for profit, and stole cultural artifacts that now collect dust in their museums. Thus, so the story goes, blame for many of the world’s current problems lies squarely at the feet of the British Empire, for which she should still be paying reparations.

Yet, Black notes, “there is sometimes a failure to appreciate the extent to which Britain generally was not the conqueror of native peoples ruling themselves in a democratic fashion, but, instead, overcame other imperial systems, and that the latter themselves rested on conquest.” Take, for example, the Indian subcontinent, which was a disparate collection of kingdoms and competing empires — including Mughals, Sikhs, Afghan Durranis — during the early centuries of British intervention. All of these were plenty brutal and intolerant towards those they subjugated. Moreover, Hinduism promoted not only the oppressive caste system, but also sati, or the ritual of widow burning, in which widows were either volitionally or forcibly placed upon the funeral pyres of their deceased husbands. It was the British who stopped this practice, and others, with such legislation as the Hindu Widows’ Remarriage Act of 1856, the Female Infanticide Prevention Act of 1870, and the Age of Consent Act of 1891.

Nor has India been able to escape the same imperialist tendencies as the British. Just ask the Sikhs, whose demands to “free Khalistan” have gone unheeded by New Delhi, and who in 1984 suffered great atrocities at the hands of the Indian military and civilian mobs. Or ask Indian Muslims, of whom more than 1,000 died in the 2002 Gujarat riots and who suffer increasing persecution under the ruling Hindu nationalist party BJP. There’s also not a few folks in Kashmir who happen to call the Indians imperialists. One might note here that many of the problems in former European colonies are not solely, or even largely the result of European imperialism, but can be attributed to many other causes, population increase, modernization, and globalization among them. Corruption in some former colonies, including India, is almost certainly higher than it was during British rule.

India is only one such example where the modern narrative ignores both historical and contemporary realities, including, one might add, the fact that India as it now exists is largely a creation of British colonial efforts. It was Britain that united a disparate group of people into a single cohesive unit with a national identity. Indeed, as Black rightly notes, “modern concepts of nationality have generally been employed misleadingly to interpret the policies and politics of the past.”

This is further complicated by the fact that in many places, especially India, “alongside hostility, opposition and conflict,” between the imperialists and the colonized, “there was inter-marriage, intermixing, compromise, co-existence, and the process of negotiation that is sometimes referred to as the ‘middle-ground.'” One need look no further than the First and Second World Wars, in which more than 1.5 million and approximately 2.5 million Indians, respectively, fought willingly and bravely in the service of the British crown.

August 16, 2019

Rule Britannia, Britannia Rules the Salt | BETWEEN 2 WARS I 1930 Part 1 of 1

TimeGhost History

Published on 15 Aug 2019After the Great War, the British empire is at its peak in terms of population and size. However, resistance against colonialism is starting to brew in the British colonies and dominions.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Spartacus Olsson and Francis van Berkel

Directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Francis van Berkel

Edited by: Wieke Kapteijns

Sound design: Iryna DulkaPortrait Colorizations by Daniel Weiss.

Sources: National Portrait Gallery, Library and Archives Canada, Jenny Scott

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

August 15, 2019

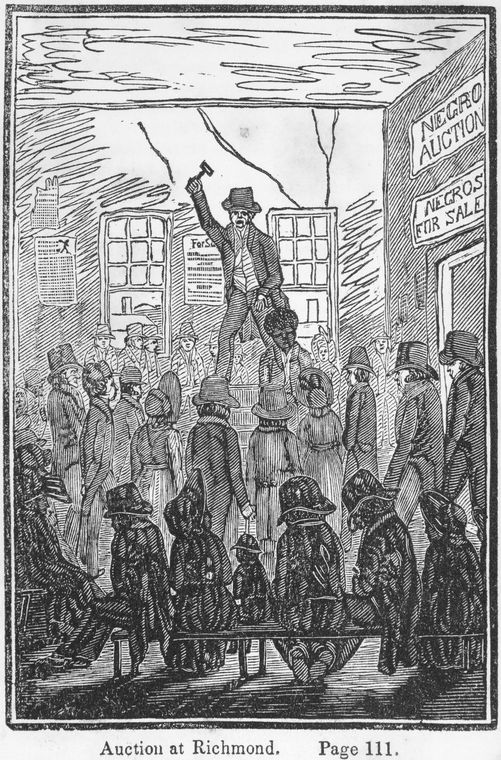

Slavery in the American colonies

Tim Worstall outlines the history of slavery in the area under British rule that eventually became the United States:

This is so well known, what did in fact happen, that even Wikipedia has it unencumbered by wokeness.

Auction at Richmond. (1834)

“Five hundred thousand strokes for freedom; a series of anti-slavery tracts, of which half a million are now first issued by the friends of the Negro.” by Armistead, Wilson, 1819?-1868 and “Picture of slavery in the United States of America” by Bourne, George, 1780-1845

New York Public Library via Wikimedia Commons.

The first 19 or so Africans to reach the English colonies arrived in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619, brought by English privateers who had seized them from a captured Portuguese slave ship. Slaves were usually baptized in Africa before embarking. As English custom then considered baptized Christians exempt from slavery, colonists treated these Africans as indentured servants, and they joined about 1,000 English indentured servants already in the colony. The Africans were freed after a prescribed period and given the use of land and supplies by their former masters. The historian Ira Berlin noted that what he called the “charter generation” in the colonies was sometimes made up of mixed-race men (Atlantic Creoles) who were indentured servants, and whose ancestry was African and Iberian. They were descendants of African women and Portuguese or Spanish men who worked in African ports as traders or facilitators in the slave trade. For example, Anthony Johnson arrived in Virginia in 1621 from Angola as an indentured servant; he became free and a property owner, eventually buying and owning slaves himself. The transformation of the social status of Africans, from indentured servitude to slaves in a racial caste which they could not leave or escape, happened gradually.

There were no laws regarding slavery early in Virginia’s history. But, in 1640, a Virginia court sentenced John Punch, an African, to slavery after he attempted to flee his service. The two whites with whom he fled were sentenced only to an additional year of their indenture, and three years’ service to the colony. This marked the first legal sanctioning of slavery in the English colonies and was one of the first legal distinctions made between Europeans and Africans.

That’s the 1640 start, if you prefer that. When the distinction was made between black and white runaways from that indenture.

Worth noting that there was nothing unusual about indenture. Very similar indeed to the idea and practice of apprenticeship at the time. In effect, a time limited ownership of the labor – not the person – in return for certain benefits such as transport, sustenance, training and so on. This was actually the manner in which anyone at all entered the skilled working class. Sure, it all sounds a bit feudal but then that’s because it was rather the overhang of that feudal system. And it really did apply to people irrespective of skin colour or racial – even national – background.

England hadn’t had chattel slavery since the Anglo Saxons – Scotland and certain miners being evidence that all of Britain wasn’t so lucky – and it was rather more the Moors, Ottomans, Arabs, various places below the Olive Line, who still had full on slavery.

This then full changed in the colonies. And Anthony Johnson, that arrival from Angola in 1621, who makes the history here:

When Anthony Johnson was released from servitude, he was legally recognized as a “free Negro.” He became a successful farmer. In 1651 he owned 250 acres (100 ha), and the services of five indentured servants (four white and one black). In 1653, John Casor, a black indentured servant whose contract Johnson appeared to have bought in the early 1640s, approached Captain Goldsmith, claiming his indenture had expired seven years earlier and that he was being held illegally by Johnson. A neighbor, Robert Parker, intervened and persuaded Johnson to free Casor.

Parker offered Casor work, and he signed a term of indenture to the planter. Johnson sued Parker in the Northampton Court in 1654 for the return of Casor. The court initially found in favor of Parker, but Johnson appealed. In 1655, the court reversed its ruling. Finding that Anthony Johnson still “owned” John Casor, the court ordered that he be returned with the court dues paid by Robert Parker.

This was the first instance of a judicial determination in the Thirteen Colonies holding that a person who had committed no crime could be held in servitude for life. Though Casor was the first person declared a slave in a civil case, there were both black and white indentured servants sentenced to lifetime servitude before him.

That first instance of that full on chattel slavery in the colonies that became the US was firstly in 1655 – we even know the date, March 8 – and it was of a black owning a black. Oh, and free blacks owning slaves themselves was something that never did entirely disappear from American life, not until slavery itself did in the 1860s.

This all is more than mere pendantry too. Because slavery was not simply the invention of white Europeans to oppress black Africans. A few places in NW Europe – see England above – didn’t have slavery for several hundred years before the Atlantic trade. The rest of the world carried on, quite gaily, having it. To the point that the very word “Slav” is cognate with slave. The Mamluks who ruled Egypt were a caste of mercenaries composed of slaves. The Ottoman Sultan took as his tribute from the Balkans and elsewhere male children who were then sent to Egypt to enlist. Their own children could not join that ruling caste and army. It was a non-hereditary ruling army of slaves, weird as it may seem. Africa itself was awash with slavery and the Arab slave trade up into North Africa and the Mediterranean was a trade in something already happening.

August 12, 2019

Hogs in History – Creator and Destroyer – Extra History

Extra Credits

Published on 10 Aug 2019Download the World of Tanks game for free https://tanks.ly/2yj0usN and use the invite code

EXTRATANKS1to claim your $15 starter pack.In 1494, among the colonization forces from Spain, eight pigs arrived in Cuba. With multiple uses in culinary and craft trades, as well as their general top-tier hardiness, pigs would naturally propagate themselves throughout the Caribbean, and then to Central, South, and North America — but they were also incredibly destructive.

Visit TierZoo to learn about how OP pigs are: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6xbQ2…

Join us on Patreon! http://bit.ly/EHPatreon

July 29, 2019

Erasing the past, statue by statue, plaque by plaque

Alexander Adams on the deliberate sabotage of historical monuments in pursuit of a more perfect (i.e., imaginary) past:

End of the Trail by James Earle Fraser, located in Waupun, Wisconsin.

Photo by Shawn Conrad via Wikimedia Commons.

In the wake of recent attempts – some successful – to have Confederate statues removed from the US south, what is the future of colonialist statues in the US west? In Pioneer Mother Monuments: Constructing Cultural Memory, Cynthia Culver Prescott, a professor of history at the University of North Dakota, senses a reluctance to apply to pioneer monuments the ideological zeal that was turned on Confederate memorials. “We resist applying the insights of settler colonial studies to American pioneer narratives because to do so would call into question foundational myths of Jeffersonian agrarianism and American exceptionalism, and lay bare white conquest of native lands and peoples.” She outlines the cases against statues of colonialists, and particularly against female settlers, who took part in the drive to colonise the American west in the 19th century.

Statues depicting women have been criticised by academics and campaigners for being idealising, inaccurate, generalising and stereotypical. There is a sense that campaigners direct such ire at statues of women settlers not just because they embody sexism and colonialism but because they show women as complicit in the act of dispossessing native peoples. There is a residual resentment that – in intersectional terms – a political minority took part in a project to oppress another minority.

The creation of monuments honouring white settlers of the west began in earnest in the 1890s. As the American western frontier was closed and territories became part of the United States, a chapter of national history had been definitively closed, too. Just under 190 monuments have been erected in the US since the 1880s marking pioneer achievements. It was a way of fixing in collective memory the achievements of forebears just at the moment their stories were becoming history. The western territories had been spared the scourge of the Civil War, and its new states had a history that involved war with Mexico, the persecution and flight of the Mormons and the Indian Wars.

In the statuary, common types emerged. Women were the prairie Madonna, the protective mother, the Indian guide leading the way, the nuclear family. Men were resolute fathers, the epitome of bravery and stoic defiance. Competitions, touring exhibitions, newspaper features and book publications circulated them, encouraging other communities to commission similar statues. Alexander Phimister Proctor’s statue of a male pioneer was an acceptable manifestation of the conquering of the west. Bearded and dressed in buckskin clothing, the pioneer wears European boots and carries a rifle. He straddles the wisdom of the natives and the technological superiority of settlers, explaining how the west was won through a combination of old knowledge and new materials.

Culver Prescott notes the example of James Earle Fraser’s sculpture The End of the Trail (1890s), which depicted an exhausted American Indian on a tired pony. Fraser had apparently developed a deep sympathy for native peoples after witnessing an army eviction. It seems the sculptor intended to elicit sympathy for evicted Indians, yet it was interpreted by contemporary observers as a scene of the sad but necessary extinction of a primitive indigenous people, conforming to the social Darwinist reading of history, in which advanced people defeat and displace inferior peoples. This is an object lesson in the variety of interpretations an artwork can elicit, regardless of artistic intent. It should alert today’s social-justice warriors to the dangers of misinterpreting public art and the risk of suppressing art on the basis of misapprehension.

July 20, 2019

“Boris Johnson is the only man alive who could convincingly turn The Emperor’s New Clothes into a one-man play”

In Spiked, Alaa al-Ameri says that Boris Johnson actually does have a valid point in his criticism of Islam:

Boris Johnson, Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs at an informal meeting of the Foreign Affairs Council on 15 February 2018.

Photo by Velislav Nikolov via Wikimedia Commons.

Boris Johnson is the only man alive who could convincingly turn The Emperor’s New Clothes into a one-man play. He’s perfect for every role – the pompous, bumbling, vain emperor; the barefaced conmen trafficking in audacious whoppers; and, most importantly, the little boy, unable to keep from blurting out the obvious, especially when everyone around him is busy parroting the convenient lie of the day.

Not for the first time, Johnson has offended polite society by suggesting that there might be something less than perfectly laudable about some aspects of Islam. Perish the thought. In particular, offence-miners at the Guardian have discovered that Johnson once wrote that Islam has held Muslim countries back by “centuries”.

A cursory look around the world is enough to conclude that there may be something to Johnson’s argument. A deeper look at Arab and Muslim history – both ancient and recent – might at least confirm the possibility that such a statement is something other than flat-out bigotry. Or so you might have thought, if you had recently awoken from a 30-year coma. In 2019, however, such thoughts are unthinkable.

We can moralise all day long about the evils of European colonialism. But it was a historical blink of an eye in comparison to the centuries of Arab and Muslim colonialism that produced the cultures to which Johnson was referring. We can wring our hands over the influence of literalist Christianity on American politics. But this is a drop in the ocean compared to the cultural and political leverage of Islam across the globe. We can lament the potential harm to Indian democracy posed by militant Hindu nationalism. But there is nothing questionable about entertaining the notion that centuries of Muslim global imperialism – which ended less than 100 years ago – might have left behind a less than a gleaming legacy.

May 12, 2019

QotD: The British Army between the wars

In the nineteenth century the British common soldier was usually a farm labourer or slum proletarian who had been driven into the army by brute starvation. He enlisted for a period of at least seven years – sometimes as much as twenty-one years – and he was inured to a barrack life of endless drilling, rigid and stupid discipline, and degrading physical punishments. It was virtually impossible for him to marry, and even after the extension of the franchise he lacked the right to vote. In Indian garrison towns he could kick the “niggers” with impunity, but at home he was hated or looked down upon by the ordinary population, except in wartime, when for brief periods he was discovered to be a hero. Obviously such a man had severed his links with his own class. He was essentially a mercenary, and his self-respect depended on his conception of himself not as a worker or a citizen but simply as a fighting animal.

Since the war the conditions of army life have improved and the conception of discipline has grown more intelligent, but the British army has retained its special characteristics – small size, voluntary enlistment, long service and emphasis on regimental loyalty. Every regiment has its own name (not merely a number, as in most armies), its history and relics, its special customs, traditions, etc., etc., thanks to which the whole army is honey-combed with snobberies which are almost unbelievable unless one has seen them at close quarters. Between the officers of a “smart” regiment and those of an ordinary infantry regiment, or still more a regiment of the Indian Army, there is a degree of jealousy almost amounting to a class difference. And there is no question that the long-term private soldier often identifies with his own regiment almost as closely as the officer does. The effect is to make the narrow “non-political” outlook of the mercenary come more easily to him. In addition, the fact that the British Army is rather heavily officered probably diminishes class friction and thus makes the lower ranks less accessible to “subversive” ideas.

But the thing which above all else forces a reactionary view-point on the common soldier is his service in overseas garrisons. An infantry regiment is usually quartered abroad for eighteen years consecutively, moving from place to place every four or five years, so that many soldiers serve their entire time in India, Africa, China, etc. They are only there to hold down a hostile population and the fact is brought home to them in unmistakeable ways. Relations with the “natives” are almost invariably bad, and the soldiers – not so much the officers as the men – are the obvious targets for anti-British feeling. Naturally they retaliate, and as a rule they develop an attitude towards the “niggers” which is far more brutal than that of the officials or business men. In Burma I was constantly struck by the fact that the common soldiers were the best-hated section of the white community, and, judged simply by their behaviour, they certainly deserved to be. Even as near home as Gibraltar they walk the streets with a swaggering air which is directed at the Spanish “natives.” And in practice some such attitude is absolutely necessary; you could not hold down a subject empire with troops infected by notions of class-solidarity. Most of the dirty work of the French empire, for instance, is done not by French conscripts but by illiterate Negroes and by the Foreign Legion, a corps of pure mercenaries.

To sum up: in spite of the technical advances which do not allow the professional officer to be quite such an idiot as he used to be, and in spite of the fact that the common soldier is now treated a little more like a human being, the British army remains essentially the same machine as it was fifty years ago.

George Orwell, “Democracy in the British Army”, Left, 1939-09.

February 12, 2016

QotD: Military developments from 1870 onwards

The period of Colonial expansion coincided with three major developments in weapon-power: the general adoption of the small-bore magazine rifle, firing smokeless powder; the perfection of the machine gun; and the introduction of quick-firing artillery.

By 1871, the single-shot breech-loading rifle had reached so high a standard of efficiency that the next step was to convert it into a repeating, or magazine, rifle. Although the idea was an old one, it was not fully practicable until the adoption of the all-metal cartridge case, which reduced jamming in the breech. The first European power to introduce the magazine rifle was Germany who, in 1884, converted her 1871 pattern Mauser rifle to the magazine system; the magazine was of the tube type inserted in the fore-end under the barrel, it held eight cartridges. In 1885, France adopted a somewhat similar rifle, the Lebel, which fired smokeless powder — an enormous advantage. Next, in 1886, the Austrians introduced the Mannlicher with a box magazine in front of the trigger guard and below the entrance to the breech. And two years later the British adopted the .303 calibre Lee-Metford with a box magazine of eight cartridges, later increased to ten. By 1900 all armies had magazine rifles approximately of equal efficiency, and of calibres varying from .315 to .256; all were bolt operated, fired smokeless powder, and were sighted to 2,000 yards or metres.

Simultaneously with the development of the magazine rifle proceeded the development of the machine gun — another very old idea. Many types were experimented with and some adopted, such as the improved Gatling, Nordenfeldt (1873), Hotchkiss (1875), Gardner (1876), Browning (1889) and Colt (1895). The crucial year in their development was 1884, when Hiram S. Maxim patented a one barrel gun which loaded and fired itself by the force of its recoil. The original model weighed 40lb., was water cooled and belt fed, and 2,000 rounds could be fired from it in three minutes. It was adopted by the British army in 1889, and was destined to revolutionize infantry tactics.

The introduction of quick-firing artillery arose out of proposals made in 1891 by General Wille in Germany and Colonel Langlois in France. They held that increased rate of fire was impossible unless recoil on firing was absorbed. This led to much experimental work on shock absorption, and to the eventual introduction of a non-recoiling carriage, which permitted of a bullet-proof shield being attached to it to protect the gun crew. Until this improvement in artillery was introduced, the magazine rifle had been the dominant weapon, now it was challenged by the quick-firing gun, which not only outranged it and could be fired with almost equal rapidity, but could be rendered invisible by indirect laying.

J.F.C. Fuller, The Conduct of War, 1789-1961, 1961.

October 7, 2015

Argentina’s colonial history

Ralph Peters on the history of Argentina during the colonial era:

In the 19th century in the Western hemisphere, two states fought a protracted series of wars to subdue their frontiers, the United States and Argentina. Others, such as Chile or Canada, saw lesser violence, but the great wars of conquest were directed from Washington and Buenos Aires.

And the Argentine conquest appears to have been the crueler.

Settlers in the Spanish territory that became Argentina faced Indian threats from the beginning, but as the population swelled and expanded its territorial claims, the violence grew more frequent and extreme, with Indian raids on settlers similar to those experienced on the American frontier. Finally, in 1833, Juan Manuel de Rosas — a man of great vision and spectacular brutality who would rule Argentina as dictator — launched his “Desert Campaign,” which pushed back the frontier to Patagonia. Still, Indian raids continued, on and off, as did minor punitive expeditions, until the 1870s saw the years-long campaign, the “Conquest of the Desert,” that finally mastered all of Patagonia — which would become Argentina’s agricultural heartland, facilitating a turn-of-the-century economic boom.

Those wars saw a long list of massacres, atrocities, forced removals and the treatment of Argentina’s aboriginal peoples as animals, rather than humans.

When the Pope told Americans not to judge the past by today’s standards, we thought of our “Trail of Tears,” or of the last, murderous drives to contain our Indians on bleak reservations. But the Pope saw mounted troops in Argentine uniforms hunting down natives like game animals.

January 13, 2015

QotD: The high-water mark of European colonialism

… by the close of the century, eight Western European powers — Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Belgium and the Netherlands — together in extent slightly under 1,000,000 square miles, had within a generation added some 11,000,000 square miles of foreign territories to their homelands; and area three and a half times the size of the United States, and rather more than one-fifth of the land surface of the globe! So extensive a conquest had no equal since the invasions of the Mongols in the thirteenth century, and no previous conquest had been so rapid and bloodless since the age of Alexander the Great. Like his, it was destined to be followed by the wars of its Diadochi [Alexander’s successors].

J.F.C. Fuller, The Conduct of War, 1789-1961, 1961.