The Tank Museum

Published 9 Sep 2022In this episode of Tank Chats, David Fletcher details Scorpion and Sabre from the CVRT collection.

(more…)

January 12, 2023

Tank Chats #163 | Scorpion & Sabre | The Tank Museum

December 15, 2022

Kraut Space Magic: the H&K G11

Forgotten Weapons

Published 25 Dec 2018I have been waiting for a long time to have a chance to make this video — the Heckler & Koch G11! Specifically, a G11K2, the final version approved for use by the West German Bundeswehr, before being cancelled for political and economic reasons.

The G11 was a combined effort by H&K and Dynamit Nobel to produce a new rifle for the German military with truly new technology. The core of the system was the use of a caseless cartridge developed in the late 60s and early 70s by Dynamit Nobel, which then allowed H&K to design a magnificently complex action which could fire three rounds in a hyper-fast (~2000 rpm) burst and have all three bullets leave the barrel before the weapon moved in recoil.

Remarkably, the idea went through enough development to pass German trials and actually be accepted for service in the late 1980s (after a funding shutdown when it proved incapable of winning NATO cartridge selection trials a decade earlier). However, the reunification with East Germany presented a reduced strategic threat, a new surplus of East German combat rifles (AK74s), and a huge new economic burden to the combined nations and this led to the cancellation of the program. The US Advanced Combat Rifle program gave the G11 one last grasp at a future, but it was not deemed a sufficient improvement in practical use over the M16 platform to justify a replacement of all US weapons in service.

The G11 lives on, however, as an icon of German engineering prowess often referred to as “Kraut Space Magic” (in an entirely complimentary take on the old pejorative). That it could be so complex and yet still run reliably in legitimate military trials is a tremendous feat by H&K’s design engineers, and yet one must consider that the Bundeswehr may just have dodged a bullet when it ended up not actually adopting the rifle.

Many thanks to H&K USA for giving me access to the G11 rifles in their Grey Room for this video!

(more…)

December 13, 2022

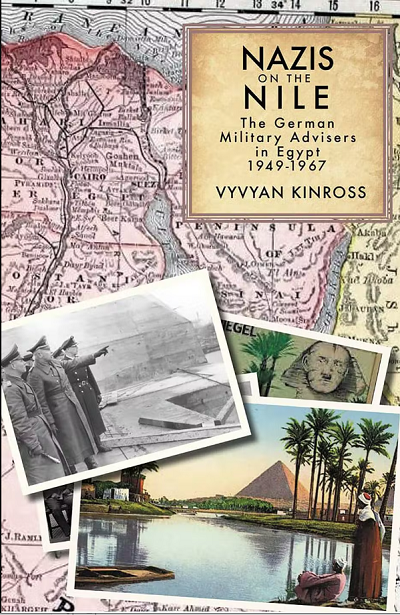

Egypt’s postwar Nazi military advisors

In The Critic, James Barr reviews a book on the roles of former Nazi military and political figures in the Egyptian forces, Nazis on the Nile: The German Military Advisers in Egypt 1949-1967 by Vyvyan Kinross:

One of the paradoxes of the early postwar era is that, after Germany’s defeat, the Nazis were vilified at the same time that their expertise was sought after by both Cold War superpowers. Germans played key roles in both sides’ space programmes. Less infamous is the part they also went on to play in the Egyptian rocket programme, one of the subjects in this fascinating and disturbing book.

After suffering a humiliating defeat in the war that followed the establishment of Israel, the Egyptians wanted revenge. As the British had refused to help them — despite maintaining a deeply unpopular and large presence astride the Suez Canal — Egypt’s sybaritic King Farouq turned to his enemy’s enemy instead. In 1949 he commissioned an Afrika Korps general, Artur Schmitt, to review the Egyptian army.

Having checked in to a Cairo hotel under the name “Herr Goldstein”, Schmitt inspected Egyptian units and went on to Syria to survey Israel from the Golan Heights. The Egyptians’ failure to combine tanks, artillery and infantry effectively, he decided, explained their “inability to take advantage of the early stages of fighting to wipe the State of Israel off the map”.

Schmitt’s forthright conclusions were unwelcome, and he did not stay long. But some younger Egyptian army officers shared his views and, after they had overthrown Farouq in 1952, they picked up where the king had left off. Within days they offered Fritz Voss, the former head of the Skoda arms factory in Pilsen, the job of masterminding the retraining of the army and the establishment of a military industrial base that could produce jet aircraft and missiles.

Voss in turn invited old contacts to join him, including Wilhelm Beisner, an SS officer who had been part of Einsatzkommando Egypt, which would have spearheaded the Holocaust in Palestine had Rommel won at El Alamein. The Germans found Egyptian working conditions challenging. “Here one has to act much more slowly than in Prussia,” complained a German instructor who found “Oriental sloppiness” irritating. Of forty tanks lined up for a parade to celebrate the first anniversary of the coup, just twelve made it past the junta’s rostrum.

The author, Vyvyan Kinross, is a consultant by profession. He has advised Arab governments and clearly understands the fundamental problems. “The battle” for the Germans, he writes, “was always to reconcile finance, resourcing and the expertise required to execute a sophisticated manufacturing process with the challenging conditions and logistics that prevailed in a country that was late to industrialise and financially underpowered.”

December 6, 2022

The coming of the Korean War

In Quillette, Niranjan Shankar outlines the world situation that led to the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950:

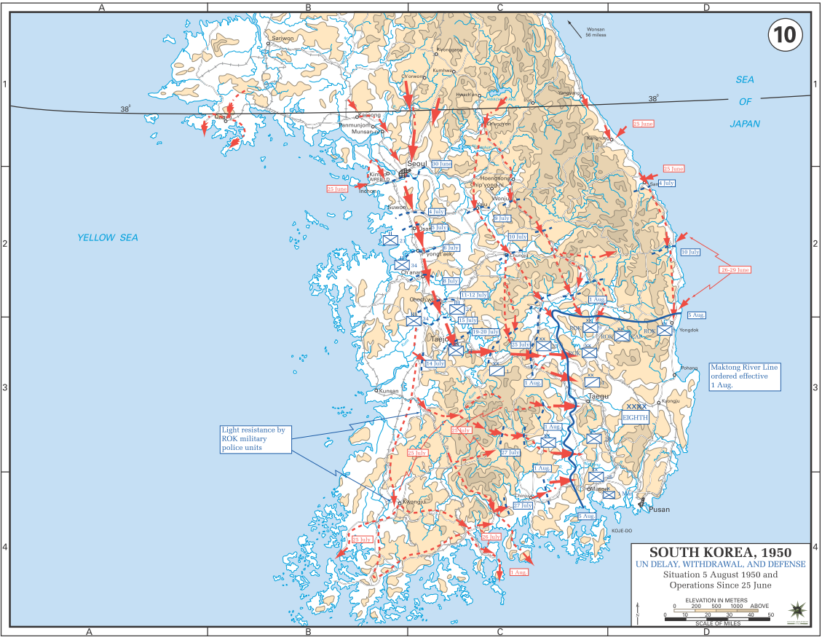

Initial phase of the Korean War, 25 June through 5 August, 1950.

Map from the West Point Military Atlas — https://www.westpoint.edu/academics/academic-departments/history/korean-war

The Korean War was among the deadliest of the Cold War’s battlegrounds. Yet despite yielding millions of civilian deaths, over 40,000 US casualties, and destruction that left scars which persist on the peninsula today, the conflict has never received the attention (aside from being featured in the sitcom M*A*S*H) devoted to World War II, Vietnam, and other 20th-century clashes.

But like other neglected Cold War front-lines, the “Forgotten War” has fallen victim to several politicized and one-sided “anti-imperialist” narratives that focus almost exclusively on the atrocities of the United States and its allies. The most recent example of this tendency was a Jacobin column by James Greig, who omits the brutal conduct of North Korean and Chinese forces, misrepresents the underlying cause of the war, justifies North Korea’s belligerence as an “anti-colonial” enterprise, and even praises the regime’s “revolutionary” initiatives. Greig’s article was preceded by several others, which also framed the war as an instance of US imperialism and North Korea’s anti-Americanism as a rational response to Washington’s prosecution of the war. Left-wing foreign-policy thinker Daniel Bessner also alluded to the Korean War as one of many “American-led fiascos” in his essay for Harper’s magazine earlier this summer. Even (somewhat) more balanced assessments of the war, such as those by Owen Miller, tend to overemphasize American and South Korean transgressions, and don’t do justice to the long-term consequences of Washington’s decision to send troops to the peninsula in the summer of 1950. By giving short shrift to — or simply failing to mention — the communist powers’ leading role in instigating the conflict, and the violence and suffering they unleashed throughout it, these depictions of the Korean tragedy distort its legacy and do a disservice to the millions who suffered, and continue to suffer, under the North Korean regime.

Determining “who started” a military confrontation, especially an “internal” conflict that became entangled in great-power politics, can be a herculean task. Nevertheless, post-revisionist scholarship (such as John Lewis Gaddis’s The Cold War: A New History) that draws upon Soviet archives declassified in 1991 has made it clear that the communist leaders, principally Joseph Stalin and North Korean leader Kim Il-Sung, were primarily to blame for the outbreak of the war.

After Korea, a Japanese imperial holding, was jointly occupied by the United States and the Soviet Union in 1945, Washington and Moscow agreed to divide the peninsula at the 38th parallel. In the North, the Soviets worked with the Korean communist and former Red Army officer Kim Il-Sung to form a provisional “People’s Committee”, while the Americans turned to the well-known Korean nationalist and independence activist Syngman Rhee to establish a military government in the South. Neither the US nor the USSR intended the division to be permanent, and until 1947, both experimented with proposals for a united Korean government under an international trusteeship. But Kim and Rhee’s mutual rejection of any plan that didn’t leave the entire peninsula under their control hindered these efforts. When Rhee declared the Republic of Korea (ROK) in 1948, and Kim declared the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) later that year, the division was cemented. Each nation threatened to invade the other and began preparing to do so.

What initially prevented a full-scale attack by either side was Washington’s and Moscow’s refusal to provide their respective partners with support for the military reunification of the peninsula. Both superpowers had withdrawn their troops by 1949 to avoid being dragged into an unnecessary war, and the Americans deliberately withheld weapons from the ROK that could be used to launch an invasion.

However, Stalin began to have other ideas. Emboldened by Mao Zedong’s victory in the Chinese Civil War and frustrated by strategic setbacks in Europe, the Soviet premier saw an opportunity to open a “second-front” for communist expansion in East Asia with Beijing’s help. Convinced that Washington was unlikely to respond, Stalin gave Kim Il-Sung his long-sought “green-light” to reunify the Korean peninsula under communist rule in April 1950, provided that Mao agreed to support the operation. After Mao convinced his advisers (despite some initial difficulty) of the need to back their Korean counterparts, Red Army military advisers began working extensively with the Korean People’s Army (KPA) to prepare for an attack on the South. When Kim’s forces invaded on June 25th, 1950, the US and the international community were caught completely off-guard.

Commentators like Greig, who contest the communists’ culpability in starting the war, often rely on the work of revisionist historian Bruce Cumings, who highlights the perpetual state of conflict between the two Korean states before 1950. It is certainly true that there were several border skirmishes over the 38th parallel after the Soviet and American occupation governments were established in 1945. But this in no way absolves Kim and his foreign patrons for their role in unleashing an all-out assault on the South. Firstly, despite Rhee’s threats and aggressive posturing, the North clearly had the upper hand militarily, and was much better positioned than the South to launch an invasion. Whereas Washington stripped Rhee’s forces of much of their offensive capabilities, Moscow was more than happy to arm its Korean partners with heavy tanks, artillery, and aircraft. Many KPA soldiers also had prior military experience from fighting alongside the Chinese communists during the Chinese Civil War.

Moreover, as scholar William Stueck eloquently maintains, the “civil” aspect of the Korean War fails to obviate the conflict’s underlying international dimensions. Of course, Rhee’s and Kim’s stubborn desire to see the country fully “liberated” thwarted numerous efforts to establish a unified Korean government, and played a role in prolonging the war after it started. It is unlikely that Stalin would have agreed to support Pyongyang’s campaign to reunify Korea had it not been for Kim’s persistent requests and repeated assurances that the war would be won quickly. Nevertheless, the extensive economic and military assistance provided to the North Koreans by the Soviets and Chinese (the latter of which later entered the war directly), the subsequent expansion of Sino-Soviet cooperation, the Stalinist nature of the regime in Pyongyang, Kim’s role in both the CCP and the Red Army, and the close relationship between the Chinese and Korean communists all strongly suggest that without the blessing of his ideological inspirators and military supporters, Kim could not have embarked on his crusade to “liberate” the South.

Likewise, Rhee’s education in the US and desire to emulate the American capitalist model in Korea were important international components of the conflict. More to the point, all the participants saw the war as a confrontation between communism and its opponents worldwide, which led to the intensification of the Cold War in other theaters as well. The broader, global context of the buildup to the war, along with the UN’s authorization for military action, legitimized America’s intervention as a struggle against international communist expansionism, rather than an unwelcome intrusion into a civil dispute among Koreans.

QotD: Mao Zedong’s theory of “Protracted War”

The foundation for most modern thinking about this topic begins with Mao Zedong’s theorizing about what he called “protracted people’s war” in a work entitled – conveniently enough – On Protracted War (1938), though while the Chinese Communist Party would tend to subsequently represent the ideas there are a singular work of Mao’s genius, in practice he was hardly the sole thinker involved. The reason we start with Mao is that his subsequent success in China (though complicated by other factors) contributed to subsequent movements fighting “wars of national liberation” consciously modeled their efforts off of this theoretical foundation.

The situation for the Chinese Communists in 1938 was a difficult one. The Chinese Red Army has set up a base of power in the early 1930s in Jiangxi province in South-Eastern China, but in 1934 had been forced by Kuomintang Nationalist forces under Chiang Kai-shek to retreat, eventually rebasing over 5,000 miles away (they’re not able to straight-line the march) in Shaanxi in China’s mountainous north in what became known as The Long March. Consequently, no one could be under any illusions of the relative power of the Chiang’s nationalist forces and the Chinese Red Army. And then, to make things worse, in 1937, Japan had invaded China (the Second Sino-Japanese War, which was a major part of WWII), beating back the Nationalist armies which had already shown themselves to be stronger than the Communists. So now Mao has to beat two armies, both of which have shown themselves to be much stronger than he is (though in the immediate term, Mao and Chiang formed a “United Front” against Japan, though tensions remained high and both sides expected to resume hostilities the moment the Japanese threat was gone). Moreover, Mao’s side lacks not only the tools of war, but the industrial capacity to build the tools of war – and the previous century of Chinese history had shown in stark terms how difficult a situation a non-industrial force faced in squaring off against industrial firepower.

That’s the context for the theory.

What Mao observed was that a “war of quick decision” would be one that the Red Army would simply lose. Because he was weaker, there was no way to win fast, so trying to fight a “fast” war would just mean losing. Consequently, a slow war – a protracted war – was necessary. But that imposes problems – in a “war of quick decision” the route to victory was fairly clear: destroy enemy armed forces and seize territory to deny them the resources to raise new forces. Classic Clausewitzian (drink!) stuff. But of course the Red Army couldn’t do that in 1938 (they’d just lose), so they needed to plan another potential route to victory to coordinate their actions. That is, they need a strategic framework – remember that strategy is the level of military analysis where we think about what our end goals should be and what methods we can employ to actually reach those goals (so that we are not just blindly lashing out but in fact making concrete progress towards a desired end-state).

Mao understands this route as consisting of three distinct phases, which he imagines will happen in order as a progression and also consisting of three types of warfare, all of which happen in different degrees and for different purposes in each phase. We can deal with the types of warfare first:

- Positional Warfare is traditional conventional warfare, attempting to take and hold territory. This is going to be done generally by the regular forces of the Red Army.

- Mobile Warfare consists of fast-moving attacks, “hit-and-run”, performed by the regular forces of the Red Army, typically on the flanks of advancing enemy forces.

- Guerrilla Warfare consists of operations of sabotage, assassination and raids on poorly defended targets, performed by irregular forces (that is, not the Red Army), organized in the area of enemy “control”.

The first phase of this strategy is the enemy strategic offensive (or the “strategic defensive” from the perspective of Mao). Because the enemy is stronger and pursuing a conventional victory through territorial control, they will attack, advancing through territory. In this first phase, trying to match the enemy in positional warfare is foolish – again, you just lose. Instead, the Red Army trades space for time, falling back to buy time for the enemy offensive to weaken rather than meeting it at its strongest, a concept you may recall from our discussions of defense in depth. The focus in this phase is on mobile warfare, striking at the enemy’s flanks but falling back before their main advances. Positional warfare is only used in defense of the mountain bases (where terrain is favorable) and only after the difficulties of long advances (and stretched logistics) have weakened the attacker. Mobile warfare is supplemented by guerrilla operations in rear areas in this phase, but falling back is also a key opportunity to leave behind organizers for guerrillas in the occupied zones that, in theory at least, support the retreating Red Army (we’ll come back to this).

Eventually, due to friction (drink!) any attack is going to run out of steam and bog down; the mobile warfare of the first phase is meant to accelerate this, of course. That creates a second phase, “strategic stalemate” where the enemy, having taken a lot of territory, is trying to secure their control of it and build new forces for new offensives, but is also stretched thin trying to hold and control all of that newly seized territory. Guerrilla attacks in this phase take much greater importance, preventing the enemy from securing their rear areas and gradually weakening them, while at the same time sustaining support by testifying to the continued existence of the Red Army. Crucially, even as the enemy gets weaker, one of the things Mao imagines for this phase is that guerrilla operations create opportunities to steal military materiel from the enemy so that the factories of the industrialized foe serve to supply the Red Army – safely secure in its mountain bases – so that it becomes stronger. At the same time (we’ll come back to this), in this phase capable recruits are also be filtered out of the occupied areas to join the Red Army, growing its strength.

Finally in the third stage, the counter-offensive, when the process of weakening the enemy through guerrilla attacks and strengthening the Red Army through stolen supplies, new recruits and international support (Mao imagines the last element to be crucial and in the event it very much was), the Red Army can shift to positional warfare again, pushing forward to recapture lost territory in conventional campaigns.

Through all of this, Mao stresses the importance of the political struggle as well. For the guerrillas to succeed, they must “live among the people as fish in the sea”. That is, the population – and in the China of this era that meant generally the rural population – becomes the covering terrain that allows the guerrillas to operate in enemy controlled areas. In order for that to work, popular support – or at least popular acquiescence (a village that doesn’t report you because it supports you works the same way as a village that doesn’t report you because it hates Chiang or a village that doesn’t report you because it knows that it will face violence reprisals if it does; the key is that you aren’t reported) – is required. As a result both retreating Red Army forces in Phase I need to prepare lost areas politically as they retreat and then once they are gone the guerrilla forces need to engage in political action. Because Mao is working with a technological base in which regular people have relatively little access to radio or television, a lot of the agitation here is imagined to be pretty face-to-face, or based on print technology (leaflets, etc), so the guerrillas need to be in the communities in order to do the political work.

Guerrilla actions in the second phase also serve a crucial political purpose: they testify to the continued existence and effectiveness of the Red Army. After all, it is very important, during the period when the main body of Communist forces are essentially avoiding direct contact with the enemy that they not give the impression that they are defeated or have given up in order to sustain will and give everyone the hope of eventual victory. Everyone there of course also includes the main body of the army holed up in its mountain bases – they too need to know that the cause is still active and that there is a route to eventual victory.

Fundamentally, the goal here is to make the war about mobilizing people rather than about mobilizing industry, thus transforming a war focused on firepower (which you lose) into a war about will – in the Clausewitzian (drink! – folks, I hope you all brought more than one drink for this …) sense – which can be won, albeit only slowly, as the slow trickle of casualties and defeats in Phase II steadily degrades enemy will, leading to their weakness and eventual collapse in Phase III.

I should note that Mao is very open that this protracted way of war would be likely to inflict a lot of damage on the country and a lot of suffering on the people. Casualties, especially among the guerrillas, are likely to be high and the guerrillas own activities would be likely to produce repressive policies from the occupiers (not that either Chiang’s Nationalists of the Imperial Japanese Army – or Mao’s Communists – needed much inducement to engage in brutal repression). Mao acknowledges those costs but is largely unconcerned by them, as indeed he would later as the ruler of a unified China be unconcerned about his man-made famine and repression killing millions. But it is important to note that this is a strategic framework which is forced to accept, by virtue of accepting a long war, that there will be a lot of collateral damage.

Now there is a historical irony here: in the event, Mao’s Red Army ended up not doing a whole lot of this. The great majority of the fighting against Japan in China was positional warfare by Chiang’s Nationalists; Mao’s Red Army achieved very little (except preparing the ground for their eventual resumption of war against Chiang) and in the event, Japan was defeated not in China but by the United States. Japanese forces in China, even at the end of the war, were still in a relatively strong position compared to Chinese forces (Nationalist or Communist) despite the substantial degradation of the Japanese war economy under the pressure of American bombing and submarine warfare. But the war with Japan left Chiang’s Nationalists fatally weakened and demoralized, so when Mao and Chiang resumed hostilities, the former with Soviet support, Mao was able to shift almost immediately to Phase III, skipping much of the theory and still win.

Nevertheless, Mao’s apparent tremendous success gave his theory of protracted war incredible cachet, leading it to be adapted with modifications (and variations in success) to all sorts of similar wars, particularly but not exclusively by communist-aligned groups.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How the Weak Can Win – A Primer on Protracted War”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-03-03.

December 4, 2022

L39A1: British Service Target Rifle Before the L42A1

Forgotten Weapons

Published 5 Aug 2022The story of the conversion of the Lee Enfield to 7.62mm NATO would not be complete without the L39A1. This is essentially the civilian competition version of what would become the L42A1. It was actually in British service as a target rifle — not intended for combat. It followed the L8 (the first British military attempts at a 7.62mm precision version of the Enfield) and the L42A1. It was basically a copy of the conversions done by civilian competition shooters in the British NRA.

Sights were made by several different companies, as the rifles were not issued with sights — they were obtained by the unit they went to, whatever particular model that unit preferred. This example has Parker Hale diopter sights. The L39A1 also used a .303 caliber magazine, as they were intended for slow-fire, single-loaded competition but the magazine was used as a loading tray. The .303 magazine will not reliably hold 7.62mm cartridges, but 7.62mm conversion magazines can be put in the L39A1 and will then work just fine. They also sometimes are fitted with .303 extractors. The stock here has a semi-pistol grip a bit less substantial than the L8 .22 rifle, although most had standard No4 stocks.

The original sights were removed, and remarked as L39A1. They were made in 1969, 1970, and 1972, with a single serial number range used for the L39A1, the pretrial trials examples of the L39, and the “7.62 Conv” rifles. A total of 1,213 L39A1 rifles were made, with the other types accounting for about 28 additional rifles.

(more…)

November 29, 2022

Near Peer: Russia

Army University Press

Published 25 Nov 2022AUP’s Near Peer film series continues with a timely discussion of Russia and its military. Subject matter experts discuss Russian history, current affairs, and military doctrine. Putin’s declarations, advances in military technology, and Russia’s remembrance of the Great Patriotic War are also addressed. “Near Peer: Russia” is the second film in a four-part series exploring America’s global competitors.

Tank Chat #159 | Warrior | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 29 Jul 2022Join David Willey for a new Tank Chat on Warrior.

(more…)

November 27, 2022

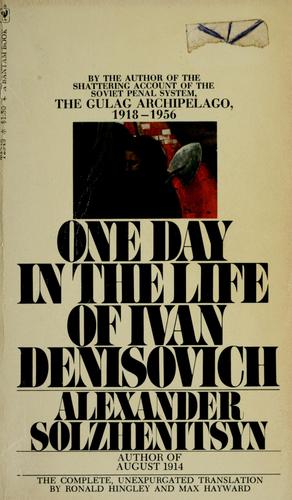

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

In Quillette, Robin Ashenden discusses the life experiences of Aleksandr Slozhenitsyn that informed the novel that made him famous:

The book was published less than 10 years after the death of Joseph Stalin, the dictator who had frozen his country in fear for nearly three decades and subjected his people to widespread deportation, imprisonment, and death. His successor Nikita Khrushchev — a man who, by his own admission, came to the job “elbow deep in blood” — had set out on a redemptive mission to liberalise the country. The Gulags had been opened and a swathe of prisoners freed; Khrushchev had denounced his predecessor publicly as a tyrant and a criminal and, at the 22nd Party Congress in October 1961, a full programme of de-Stalinisation had been announced. As for the Arts, previously neutered by the Kremlin’s policy of “Socialist Realism” — in which the values of Communism had to be resoundingly affirmed — they too were changing. Now, a new openness and a new realism was called for by Khrushchev’s supporters: books must tell the truth, even the uncomfortable truth about Communist reality … up to a point. That this point advanced or retreated as Khrushchev’s power ebbed and flowed was something no writer or publisher could afford to miss.

Solzhenitsyn’s book told the story of a single day in the 10-year prison-camp sentence of a Gulag inmate (or zek) named Ivan Denisovich Shukhov. Following decades of silence about Stalin’s prison-camp system and the innocent citizens languishing within it, the book’s appearance seemed to make the ground shake and fissure beneath people’s feet. “My face was smothered in tears,” one woman wrote to the author after she read it. “I didn’t wipe them away or feel ashamed because all this, packed into a small number of pages … was mine, intimately mine, mine for every day of the fifteen years I spent in the camps.” Another compared his book to an “atomic bomb”. For such a slender volume — about 180 pages — the seismic wave it created was a freak event.

As was the story of its publication. By the time it came out, there was virtually no trauma its author — a 44-year-old married maths teacher working in the provincial city of Ryazan — had not survived. After a youth spent in Rostov during the High Terror of Stalin’s 1930s, Solzhenitsyn had gone on to serve eagerly in the Red Army at the East Prussian front, before disaster struck in 1945. Arrested for some ill-considered words about Stalin in a letter to a friend, he was handed an eight-year Gulag sentence. In 1953, he was sent into Central Asian exile, only to be diagnosed with cancer and given three weeks to live. After a miraculous recovery, he vowed to dedicate this “second life” to a higher purpose. His writing, honed in the camps, now took on the ruthless character of a holy mission. In this, he was fortified by the Russian Orthodox faith he’d rediscovered during his sentence, and which had replaced his once-beloved, now abandoned Marxism.

Solzhenitsyn had, since his youth, wanted to make his mark as a Russian writer. In the Gulag, he’d written cantos of poetry in his head, memorized with the help of matchsticks and rosary beads to hide it from the authorities. During his Uzbekistan exile, he’d follow a full day’s work with hours of secret nocturnal writing about the darker realities of Soviet life, burying his tightly rolled manuscripts in a champagne bottle in the garden. Later, reunited with the wife he’d married before the war, he warned her to expect no more than an hour of his company a day — “I must not swerve from my purpose.” No friendships — especially close ones — were allowed to develop with his fellow Ryazan teachers, lest they take up valuable writing time, discover his perilous obsession, or blow his cover. Subterfuge became second nature: “The pig that keeps its head down grubs up the tastiest root.” Yet throughout it all, he was sceptical that his work would ever be available to the general public: “Publication in my lifetime I must put out of my mind.”

After the 22nd Party Congress, however, Solzhenitsyn recognised that the circumstances were at last propitious, if all too fleeting. “I read and reread those speeches,” he wrote later, “and the walls of my secret world swayed like curtains in the theatre … had it arrived, then, the long-awaited moment of terrible joy, the moment when my head must break water?” It seemed that it had. He got out one of his eccentric-looking manuscripts — double-sided, typed without margins, and showing all the signs of its concealment — and sent it to the literary journal of his choice. That publication was the widely read, epoch-making Novy Mir (“New World”), a magazine whose progressive staff hoped to drag society away from Stalinism. They had kept up a steady backwards-forwards dance with the Khrushchev regime throughout the 1950s, invigorated by the thought that each new issue might be their last.

November 25, 2022

Canada’s all-purpose VTOL transport that could have changed everything; the Canadair CL-84 Dynavert

Polyus Studios

Published 14 Jul 2018The program that developed the CL-84 lasted for almost 20 years and produced one of the most successful VTOL aircraft ever, as far as performance. Canadair produced four Dynavert’s over those 20 years and two of them crashed. In fact one crashed twice. The story of the great CL-84 is one of perseverance and missed potential.

(more…)

November 20, 2022

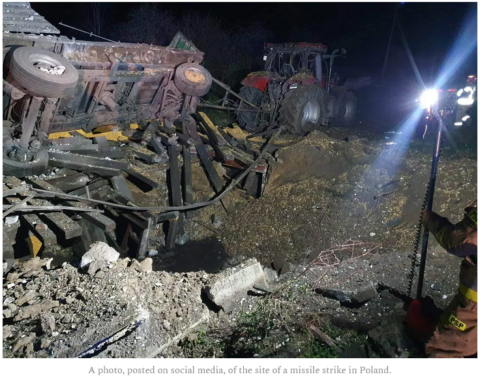

Cold War echoes on the Polish-Ukrainian border

In The Line, what Matt Gurney calls a “surprise fire drill” for a potential nuclear war:

Those with any memory of the Cold War probably got a bit of a cardio workout even if they were sitting still earlier this week when Polish news sources, which were quickly matched by American ones, reported that a Russian missile had landed in Poland, killing two civilians. An armed attack by Russia, in other words, on a NATO member state, even if a likely accidental one — Russia was bombing targets in Ukraine at the time and the site of the Polish blast was quite near the border with its embattled neighbour.

Still. Oops.

It didn’t take long before doubt emerged. At present, the official theory offered by Poland and accepted by NATO is that the missile that killed the two unfortunate Poles was actually a Ukrainian air-defence missile that was fired at incoming Russian missiles in self-defence. It somehow malfunctioned and landed in Poland. The Ukrainians themselves seem unconvinced and there are certainly those wondering if a wayward Ukrainian missile is a cover story to de-escalate a Russian mistake. Personally, I’d guess no. It probably was a Ukrainian missile. And if it is all a cover story in the cause of keeping tension between Moscow and the West at a low-sweat stage, I can live with that, for now.

The point isn’t for me to pretend I’m a munitions expert, capable of instantly solving the case with only the briefest glance at photos of a fragment of twisted missile debris. It’s more to consider what this event felt like, and what it easily could have been: one of the scarier scenarios Western officials and analysts have been worried since this war began nine months ago — accident kicking off a conflict neither side wanted but neither will back down from once it’s begun.

This isn’t a new fear. It was a fear during the Cold War. And a justified one. At several points during that long standoff, technical malfunctions or political miscalculations raised the danger of a nuclear war to horrifying levels. On a few occasions American defense commanders wrongly believed that the Soviets were launching an attack; luckily for everyone, the Americans had redundancies and were well trained and cooler heads always prevailed. In 1983, Soviet satellites reported the Americans were firing ballistic missiles at the Soviet Union. Tensions were high at the time and the Soviets had decided to launch a full strike on the West as soon as any NATO launches were detected. But Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov, a relatively low-ranked Soviet officer working the night shift, concluded that the warnings were probably a glitch — it didn’t make sense to him that America would open a surprise attack with a handful of missiles instead of the full arsenal. Rather than pass on a warning that would have triggered Soviet launches against NATO, he reported that the launch detections were a technical malfunction in the Soviet equipment. He did that again when further launches were detected. Lt. Col. Petrov then spent a few long and anxious minutes waiting to see if any NATO nuclear weapons exploded over targets in the Soviet Union. Waiting to see what happened was the only way the colonel could know if he’d made the right call, or a very, very bad one.

He was right, of course. It was a glitch. New Soviet satellites were being tricked by sunlight bouncing off clouds at high altitude. But for a few minutes, the fate of the world hung on one mid-ranked Soviet officer’s middle-of-the-night judgment call.

These real-life examples are horrifying. But learning of them never hit me quite as hard as the fictional scenario portrayed in the 1962 film Fail-Safe. Released around the same time as the more famous Doctor Strangelove, Fail-Safe, adapted from the novel Red Alert, was a grimly serious counterpart to Kubrick’s dark comedy. With an all-star cast that includes Walter Matthau and Henry Fonda, Fail-Safe depicts a series of small accidents that result in a group of American bomber pilots concluding that they have been ordered to conduct a retaliatory strike on the Soviet Union. There is no war. It’s entirely a misunderstanding, a fluke of American technological glitches and Soviet jamming. But the American pilots, trained to expect Soviet tricks and lies and to accept no order to abort (as such an order could be faked) relentlessly bore in on their targets, truly believing that they are avenging a Soviet strike on America.

Tank Chat #158 Spartan and Stormer | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 22 Jul 2022David Fletcher is back with the next Tank Chat instalment! This week he chats about not one but two vehicles, Spartan and Stormer.

(more…)

November 5, 2022

Psyops in theory and practice

Theophilus Chilton on the development of psyops and some examples of their use in US civilian contexts in recent years:

I trust that most readers are familiar with the concept of a “psyop”, a psychological operation designed to sway its targets in certain desired directions. Many of the mechanics of psyops were pioneered by the CIA and other intelligence agencies during the Cold War but have now been turned against civilian populations in the USA and elsewhere in an effort by the Regime to maintain control and minimise opposition to its various agendas. However, I’d like to make the point that psyops qualitatively differ from standard, run-of-the-mill propaganda such as governments have used for millennia.

The difference is primarily that of the time preferences involved. Whether it’s designed to whip up a population against an enemy or to try to obfuscate the truth about some particular event that has occurred, propaganda tends to operate on a shorter timescale and with more limited and simple policy goals in mind. It’s not surprising that modern propaganda techniques share a lot in common with commercial advertising designed to induce an “impulse buy” response in potential customers. Propaganda generally operates the same way — create a monodirectional response to a particular stimulus.

Psyops, on the other hand, are quite a bit more complex and generally involve the building of a narrative memeplex over the course of months, years, or even decades. Psyops are, of course, also fake but theirs is a fakeness that builds upon constant, repetitious narrative-building that lays out a foundational lens through which any individual incident or act can be systematically interpreted, adding them to the overall saga being told.

With conventional propaganda, the aim is to communicate Regime diktat to the average citizen. However, it does not necessarily expect the recipients to believe the propaganda, but merely comply with the goals. The Powers That Be in such cases don’t care why Havel’s greengrocer puts the sign up in his window, but merely that he does so. The primary purpose of psyops, on the other hand, is to ensure compliance by convincing the target to self-comply, rather than it having to be done by outside force or persuasion. It’s always touch and go when you’re making someone outwardly comply but inwardly they’re dissident. When the mark can be convinced to willingly self-police, this makes the government’s job easier since they don’t have to worry about this closet dissidence. The true believer is the best believer.

In essence, propaganda aims for immediate reactive persuasion while psyops seek long-term groundlaying that gives more all-inclusive means of maintaining overarching narrative control.

Now, a lot of people out there like to think they’re immune to psyops because “hurr durr I don’t beleeb da media!!” But they’re not. Indeed, a lot of these boomercon types are just as susceptible to psyops as anyone else when the right buttons are pushed. This is because they’ve been primed for it by the systematic, society-wide preparation of the psychological battle space without their ever realising it. In many cases, the foundations for a psyop are so culturally systematic that people don’t even realise what is happening.

For example, there are a ton of people out there who would pride themselves on being independent thinkers who nevertheless believed everything that was peddled during the covid and vaccine psyops. The reason for this is because they want to think of themselves as smart, knowledgeable about science, etc. Smart People believe the Right Things, after all. That, in turn, is the result of decades of psyops that have ensconced “science” as the arbiter of morality and truth in post-Christian America. So even when the science is fake or wrong, it is still accorded a moral authority that it does not deserve.

QotD: The use of chemical weapons after WW2

During WWII, everyone seems to have expected the use of chemical weapons, but never actually found a situation where doing so was advantageous. This is often phrased in terms of fears of escalation (this usually comes packaged with the idea of MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction), but that’s an anachronism – while Bernard Brodie is sniffing around the ideas of what would become MAD as early as ’46, MAD itself only emerges after ’62). Retaliation was certainly a concern, but I think it is hard to argue that the combatants in WWII hadn’t already been pushed to the limits of their escalation capability, in a war where the first terror bombing happened on the first day. German death-squads were in the initial invasion-waves in both Poland, as were Soviet death squads in their invasion of Poland in concert with the Germans and also later in the war. WWII was an existential war, all of the states involved knew it by 1941 (if not earlier), and they all escalated to the peak of their ability from the start; I find it hard to believe that, had they thought it was really a war winner, any of the powers in the war would have refrained from using chemical weapons. The British feared escalation to a degree (but also thought that chemical weapons use would squander valuable support in occupied France), but I struggle to imagine that, with the Nazis at the very gates of Moscow, Stalin was moved either by escalation concerns or the moral compass he so clearly lacked at every other moment of his life.

Both Cold War superpowers stockpiled chemical weapons, but seem to have retained considerable ambivalence about their use. In the United States, chemical weapons seem to have been primarily viewed not as part of tactical doctrine, but as a smaller step on a nuclear deterrence ladder (the idea being that the ability to retaliate in smaller but still dramatic steps to deter more dramatic escalations; the idea of an “escalation ladder” belongs to Herman Kahn); chemical weapons weren’t a tactical option but baby-steps on the road to tactical and then strategic nuclear devices (as an aside, I find the idea that “tactical” WMDs – nuclear or chemical – could somehow be used without triggering escalation to strategic use deeply misguided). At the same time, there was quite a bit of active research for a weapon-system that had an uncertain place in the doctrine – an effort to find a use for a weapon-system the United States already had, which never quite seems to have succeeded. The ambivalence seems to have been resolved decisively in 1969 when Nixon simply took chemical weapons off of the table with an open “no first use” policy.

Looking at Soviet doctrine is harder (both because I don’t read Russian and also, quite frankly because the current epidemic makes it hard for me to get German and English language resources on the topic) The USSR was more strongly interested in chemical weapons throughout the Cold War than the United States (note that while the linked article presents US intelligence on Soviet doctrine as uncomplicated, the actual intelligence was ambivalent – with the CIA and Army intelligence generally downgrading expectations of chemical use by the USSR, especially by the 1980s). The USSR does seem to have doctrine imagine their use at the tactical and operational level (specifically as stop-gap measures for when tactical nuclear weapons weren’t available – you’d use chemical weapons on targets when you ran out of tactical nuclear weapons), but then, that had been true in WWII but when push came to shove, the chemical munitions weren’t used. The Soviets appear to have used chemical weapons as a terror weapon in Afghanistan, but that was hardly a use against a peer modern system force. But it seems that, as the Cold War wound down, planners in the USSR came around to the same basic idea as American thinkers, with the role of chemical weapons – even as more and more effective chemicals were developed – being progressively downgraded before the program was abandoned altogether.

This certainly wasn’t because the USSR of the 1980s thought that a confrontation with NATO was less likely – the Able Archer exercise in 1983 could be argued to represent the absolute peak of Cold War tensions, rivaled only by the Cuban Missile Crisis. So this steady move away from chemical warfare wasn’t out of pacifism or utopianism; it stands to reason that it was instead motivated by a calculation as to the (limited) effectiveness of such weapons.

And I think it is worth noting that this sort of cycle – an effort to find a use for an existing weapon – is fairly common in modern military development. You can see similar efforts in the development of tactical nuclear weapons: developmental dead-ends like Davy Crockett or nuclear artillery. But the conclusion that was reached was not “chemical weapons are morally terrible” but rather “chemical weapons offer no real advantage”. In essence, the two big powers of the Cold War (and, as a side note, also the lesser components of the Warsaw Pact and NATO) spent the whole Cold War looking for an effective way to use chemical weapons against each other, and seem to have – by the end – concluded on the balance that there wasn’t one. Either conventional weapons get the job done, or you escalate to nuclear systems.

(Israel, as an aside, seems to have gone through this process in microcosm. Threatened by neighbors with active chemical weapons programs, the Israelis seem to have developed their own, but have never found a battlefield use for them, despite having been in no less than three conventional, existential wars (meaning the very existence of the state was threatened – the sort of war where moral qualms mean relatively little) since 1948.)

And I want to stress this point: it isn’t that chemical munitions do nothing, but rather they are less effective than an equivalent amount of conventional, high explosive munitions (or, at levels of extreme escalation, tactical and strategic nuclear weapons). This isn’t a value question, but a value-against-replacement question – why maintain, issue, store, and shoot expensive chemical munitions if cheap, easier to store, easier to manufacture high explosive munitions are both more obtainable and also better? When you add the geopolitical and morale impact on top of that – you sacrifice diplomatic capital using such weapons and potentially demoralize your own soldiers, who don’t want to see themselves as delivering inhumane weapons – it’s pretty clear why they wouldn’t bother. Nevertheless, the moral calculus isn’t the dominant factor: battlefield efficacy – or the relative lack thereof – is.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Why Don’t We Use Chemical Weapons Anymore?”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-03-20.

November 4, 2022

Tank Chats #157 | Ferret MKII & V | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 1 Jul 2022Join David Fletcher for a new Tank Chat on the Ferret.

(more…)