… I’d also argue that the office [of Dictator as created by Sulla and then by Caesar] didn’t work for the goals of either of the men that recreated it.

For Sulla, the purpose of using the dictatorship was to offer his reforms to the Republic some degree of legitimacy (otherwise why not just force them through purely by violence without even the fig leaf of law). Sulla was a reactionary who quite clearly believed in the Republic and seems to have been honestly and sincerely attempting to fix it; he was also a brutal, cruel and inhuman man who solved all of his problems with a mix of violence and treachery. While we can’t read Sulla’s mind on why he chose this particular form, it seems likely the aim here was to wash his reforms in the patina of something traditional-sounding in order to give them legitimacy so that they’d be longer lasting, so that Sulla’s own memory might be a bit less tarnished and to make it harder for a crisis like this to occur again.

And it failed at all three potential goals.

When it comes to the legitimacy of Sulla’s reforms and the memory that congealed around Sulla himself, it is clear that he was politically toxic even among many more conservative Romans. A younger Cicero was already using Sulla’s memory to tarnish anyone associated with him in 80, casting Chrysogonus, Sulla’s freedman, as the villain of the Pro Roscio Amerino, delivered in that year. In the sources written in the following decades at best Sulla is a touchy subject best avoided; when he is discussed, it is as a villain. Our later sources on Sulla are uniform in seeing his dictatorship as lawless. Moreover, his own reforms were picked apart by his former lieutenants, with key provisions being repealed before he was even dead (in 78 BC so that’s not a long time).

Finally, of course, far from securing the Republic, Sulla’s dictatorship provided the example and opened the door for more mayhem. Crucially, Sulla had not fixed the army problem and in fact had made it worse. You may recall one benefit of the short dictatorship is that no dictator – indeed, no consul or praetor either – would be in office long enough to secure the loyalty of his army against the state. But in the second and early first century that system had broken down. Gaius Marius had been in continuous military command from 107 to 100. Moreover, the expansion of Rome’s territory demanded more military commands than there were offices and so the Romans had begun selecting proconsuls and propraetors (along with the consuls and praetors) to fill those posts. Thus Sulla was (as a result of the Social War in Italy) a legate in 90, a propraetor in 89, and consul in 88 and so had been in command for three consecutive years (albeit the first as a legate) when he decided to turn his army – which had just, under his command, besieged the rebel stronghold of Nola – against Rome in 88, precisely because his political enemies in Rome had revoked his proconsular command for 87 (by roughing up the voters, to be clear). And then Sulla has that same army under his command as a proconsul from 87 to 83, so by the time he marches on Rome the second time with the intent to mass slaughter his enemies, his soldiers have had more than half a decade under his command to develop that ironclad loyalty (and of course a confidence that if Sulla didn’t win, their service to him might suddenly look like a crime against the Republic).

Sulla actually made this problem worse, because one of the things he legislated by fiat as dictator was that the consuls were now to always stay in Italy (in theory to guard Rome, but guard it with what, Sulla never seems to have considered). That, along with Sulla having butchered quite a lot of the actual experienced and talented military men in the Senate, left a Senate increasingly reliant on special commands doled out to a handful of commanders for long periods, leading (through Pompey‘s unusual career, holding commands in more years than not between 76 and 62) to Julius Caesar being in unbroken command of a large army in Gaul from 58 to 50, by which point that army was sufficiently loyal that it could be turned against the Republic, which of course Caesar does in 49.

For Caesar, the dictatorship seems to have been purely a tool to try to legitimate his own permanent control over the Roman state. Caesar is, from 49 to 44, only in Rome for a few months at a time and so it isn’t surprising that at first he goes to the expedient of just having his appointment renewed. But it is remarkable that his move to dictator perpetuo comes immediately after the “trial balloon” of making Caesar a Hellenistic-style king (complete with a diadem, the clear visual marker of Hellenistic-style kingship) had failed badly and publicly (Plut. Caes. 61). Perhaps recognizing that so clearly foreign an institution would be a non-starter in Rome – unpopular even among the general populace who normally loved Caesar – he instead went for a more Roman-sounding institution, something with at least a pretense of tradition to it.

And if the goal was to provide himself with some legitimacy, the effort clearly catastrophically backfired. The optics of the dictatorship were, at this point, awful; as noted, the only real example anyone had to work with was Sulla, and everyone hated Sulla. Many of Caesar’s own senatorial supporters had probably been hoping, given Caesar’s repeatedly renewed dictatorship, that he would eventually at least resign out of the office (as Sulla had done), allowing the machinery of the Republic – the elections, office holding and the direction of the Senate – to return. Declaring that he was dictator forever, rather than cementing his legitimacy clearly galvanized the conspiracy to have him assassinated, which they did in just two months.

It is striking that no one after Caesar, even in the chaotic power-struggle that ensued, no one attempted to revive the dictatorship, or use it as a model to institutionalize their power, or employ its iconography or symbolism in any way. Instead, Antony, who had himself been Caesar’s magister equitum, proposed and passed a law in 44 – right after Caesar’s death – to abolish the dictatorship, make it illegal to nominate a dictator, or for any Roman to accept the office, on pain of death (App. BCiv, 3.25, Dio 44.51.2). By all accounts, the law was broadly popular. As a legitimacy-building tool, the dictatorship had been worse than useless.

So what might we offer as a final verdict on the dictatorship? As a short-term crisis office used during the early and middle republic, a tool appropriate to a small state that had highly fragmented power in its institutions to maintain internal stability, the dictatorship was very successful, though that very success made it increasingly less necessary and important as Rome’s power grew. The customary dictatorship withered away in part because of that success: a Mediterranean-spanning empire had no need of emergency officials, when its military crises occurred at great distance and could generally be resolved by just sending a new regular commander with a larger army. By contrast, the irregular dictatorship was a complete failure, both for the men that held it and for the republic it destroyed.

The real problem wasn’t the office of dictator, but the apparatus that surrounded it: the short duration of military commands, the effectiveness and depth of the Roman aristocracy (crucially undermined by Sulla and Marius) and – less discussed here but still crucial in understanding the collapse of the Republic – the willingness of the Roman elite to compromise in order to maintain social cohesion. Without those guardrails, the dictatorship became dangerous, but without them any office becomes dangerous. Sulla and Caesar, after all, both marched on Rome not as dictators, but as consuls and proconsuls. It is the guardrails, not the office, that matter.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Roman Dictatorship: How Did It Work? Did It Work?”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-03-18.

September 16, 2025

QotD: The Dictatorship in the late Roman Republic

August 4, 2025

HBO’s Rome – Ep 8 “Caesarion” – History and Story

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published 19 Feb 2025Continuing series looking at the HBO/BBC co production drama series ROME. We will look at how they chose to tell the story, at what they changed and where they stuck closer to the history.

May 2, 2025

HBO’s Rome – Ep 6 “Egeria” – History and Story

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published 30 Oct 2024This time we come to Episode 6 of Season 1 of ROME. This one is very much based around the City of Rome itself and places Antony centre stage. In the video we look at the actual history and how well the show reflects this. For more detail on the history, have a look at the videos in the Conquered and the Proud playlist.

April 10, 2025

HBO’s Rome – Ep 5 “The Ram has touched the wall” – History and Story

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published 18 Sept 2024Continuing series looking at the HBO/BBC co production drama series ROME. We will look at how they chose to tell the story, at what they changed and where they stuck closer to the history.

January 13, 2025

The Writings of Cicero – Cicero and the Power of the Spoken Word

seangabb

Published 25 Aug 2024This lecture is taken from a course I delivered in July 2024 on the Life and Writings of Cicero. It covers these topics:

• Introduction – 00:00:00

• The Deficiencies of Modern Oratory – 00:01:20

• The Greeks and Oratory – 00:06:38

• Athens: Government by Lottery and Referendum – 00:08:10

• The Power of the Greek Language – 00:17:41

• The General Illiteracy of the Ancients – 00:21:06

• Greek Oratory: Lysias, Gorgias, Demosthenes – 00:28:38

• Macaulay as Speaker – 00:34:44

• Attic and Asianic Oratory – 00:36:56

• The Greek Conquest of Rome – 00:39:26

• Roman Oratory – 00:43:23

• Cicero: Early Life – 00:43:23

• Cicero in Greece – 00:46:03

• Cicero: Early Legal Career – 00:46:03

• Cicero: Defence of Roscius – 00:47:49

• Cicero as Orator (Sean Reads Latin) – 00:54:45

• Government of the Roman Empire – 01:01:16

• The Government of Sicily – 01:03:58

• Verres in Sicily – 01:06:54

• The Prosecution of Verres – 01:11:20

• Reading List – 01:24:28

(more…)

November 10, 2024

The Sixties, Cicero, Catiline, Cato and Caesar – The Conquered and the Proud Episode 9

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published Jul 3, 2024Continuing our series on the the history of Rome from 200 BC to AD 200, this time we look at the turbulent decade following the consulship of Pompey and Crassus in 70 BC. These years saw Pompey being given major commands against the pirates and Mithridates. Men like Cicero, Caesar and Cato were on the ascendant. Cicero’s letters can make the decade seem calm, but further consideration reveals the threat and reality of political violence, seen most of all in Catiline’s conspiracy which led to a brief civil war.

In this talk we explore the themes we have already considered and consider how imperial expansion continued to change the Roman Republic.

This talk will be released in July — and as this is the month named after Julius Caesar, it seemed only appropriate to have a Caesar theme to most of the talks.

Next time we will look at the Fifties BC and the start of the Civil War in 49 BC.

November 4, 2024

Cicero 101: Life, Death & Legacy

MoAn Inc.

Published 31 Oct 2024A Bit About MoAn Inc. — Trust me, the ancient world isn’t as boring as you may think. In this series, I’ll talk you through all things Cicero. I hope you guys enjoy this wonderful book as much as all us nerds do.

(more…)

August 24, 2024

QotD: How did the Romans themselves view the change from Republic to Empire?

The Romans themselves had a lot of thoughts about the collapse of the republic. First, we should note that they were aware that something was going very wrong and we have a fair bit of evidence that at least some Romans were trying to figure out how to fix it. Sulla’s reforms (enforced at the point of a much-used sword) in 82-80 BC were an effort to fix what he saw as the progressive destabilization of the the republic going back to the tribunate of Tiberius Gracchus (133). Sulla’s solutions were hamfisted though – he assumed that if he annihilated the opposing faction, crippled the tribunate and strengthened the Senate that this would resolve all of the problems. Cicero likewise considered reforms during the 50s BCE which come out in his De re publica and De legibus. The 50s were a time of political tumult in Rome while at the same time the last years of the decade must have been loomed over by the knowledge of an impending crisis to come in 49. Cicero was never in a position to enact his idealized republic.

Overall the various Romans who contemplated reform were in a way hindered by the tendency of Roman elites to think in terms of the virtue of individuals rather than the tendency of systems. You can see this very clearly in the writings of Sallust – another Roman writing with considerable concern as the republic comes apart – who places the fault on the collapse of Roman morals rather than on any systemic problem.

We also get a sense of these feelings from the literature that emerges after Augustus takes power in 31, and here there is a lot of complexity. There is quite a lot of praise for Augustus of course – it would have been profoundly unwise to do otherwise – but also quite a lot of deep discomfort with the recent past, revealed in places like Livy’s deeply morally compromised legends of the founding of Rome or the sharp moral ambiguity in the final books of Vergil’s Aeneid. On the other hand, some of the praise for Augustus seems to have been genuine. There was clearly an awful lot of exhaustion after so many years of disruption and civil war and so a general openness to Augustus’ “restored republic”. Still, some Romans were clearly bothered by the collapse of the republic even much later; Lucan’s Pharsalia (65 AD) casts Pompey and Cato as heroes and views Caesar far more grimly.

We have less evidence for feeling in the provinces, but of course for many provincials, little would have changed. Few of Augustus’ changes would have done much to change much for people living in the provinces, whose taxes, laws and lives remained the same. They were clearly aware of what was going on and among the elite there was clearly a scramble to try to get on the right side of whoever was going to win; being on the wrong side of the eventual winner could be a very dangerous place to be. But for most regular provincials, the collapse of the Roman Republic only mattered if some rogue Roman general’s army happened to march through their part of the world.

Bret Devereaux, “Referenda ad Senatum: August 6, 2021: Feelings at the Fall of the Republic, Ancient and Medieval Living Standards, and Zombies!”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-08-06.

May 7, 2024

QotD: Cicero’s De Senectute

“Everyone wants to get old; and everyone complains once they have,” wrote Cicero in his De Senectute (On Old Age). “So great is the inconstancy and perversity of foolishness.” The De Senectute was one of the most commonly assigned books in American high schools a century ago; you can still find the old textbooks moldering in second-hand bookshops. It is one of the most thoroughly relevant books ever written, as we invariably get old if we do not die young: Why not consider what makes old age a worthwhile stage of our lives? It is a book we could wish more Americans would read, as this year’s election cycle only seems to confirm that America is an old country. The book’s message is easily conveyed: Nature is not your enemy. “In this we are wise,” Cicero writes, “we follow nature, as our best guide, almost as our god.” Cicero uses a theatrical metaphor: “Old age is the final scene in life’s drama.” The drama is penned by Nature herself: “The rest of the play is well designed; do you believe Nature neglected to consider how it all would end?”

John Byron Kuhner, “Marlene Dietrich’s War on Nature”, First Things, 2024-02-05.

February 9, 2024

His Year: Julius Caesar (59 BC)

Historia Civilis

Published Jul 5, 2016

(more…)

October 18, 2023

QotD: The role of violence in historical societies

Reading almost any social history of actual historical societies reveal complex webs of authority, some of which rely on violence and most of which don’t. Trying to reduce all forms of authority in a society to violence or the threat of violence is a “boy’s sociology”, unfit for serious adults.

This is true even in historical societies that glorified war! Taking, for instance, medieval mounted warrior-aristocrats (read: knights), we find a far more complex set of values and social bonds. Military excellence was a key value among the medieval knightly aristocracy, but so was Christian religious belief and observance, so were expectations about courtly conduct, and so were bonds between family and oath-bound aristocrats. In short there were many forms of authority beyond violence even among military aristocrats. Consequently individuals could be – and often were! – lionized for exceptional success in these other domains, often even when their military performance was at best lackluster.

Roman political speech, meanwhile, is full of words to express authority without violence. Most obviously is the word auctoritas, from which we get authority. J.E. Lendon (in Empire of Honor: The Art of Government in the Roman World (1997)), expresses the complex interaction whereby the past performance of virtus (“strength, worth, bravery, excellence, skill, capacity”, which might be military, but it might also be virtus demonstrated in civilian fields like speaking, writing, court-room excellence, etc) produced honor which in turn invested an individual with dignitas (“worth, merit”), a legitimate claim to certain forms of deferential behavior from others (including peers; two individuals both with dignitas might owe mutual deference to each other). Such an individual, when acting or especially speaking was said to have gravitas (“weight”), an effort by the Romans to describe the feeling of emotional pressure that the dignitas of such a person demanded; a person speaking who had dignitas must be listened to seriously and respected, even if disagreed with in the end. An individual with tremendous honor might be described as having a super-charged dignitas such that not merely was some polite but serious deference, but active compliance, such was the force of their considerable honor; this was called auctoritas. As documented by Carlin Barton (in Roman Honor: Fire in the Bones (2001)), the Romans felt these weights keenly and have a robust language describing the emotional impact such feelings had.

Note that there is no necessary violence here. These things cannot be enforced through violence, they are emotional responses that the Romans report having (because their culture has conditioned them to have them) in the presence of individuals with dignitas. And such dignitas might also not be connected to violence. Cicero clearly at points in his career commanded such deference and he was at best an indifferent soldier. Instead, it was his excellence in speaking and his clear service to the Republic that commanded such respect. Other individuals might command particular auctoritas because of their role as priests, their reputation for piety or wisdom, or their history of service to the community. And of course beyond that were bonds of family, religion, social group, and so on.

And these are, to be clear, two societies run by military aristocrats as described by those same military aristocrats. If anyone was likely to represent these societies as being entirely about the commission of violence, it would be these fellows. And they simply don’t.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Universal Warrior, Part III: The Cult of the Badass”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-02-05.

March 12, 2023

QotD: Philosophy

There is nothing so absurd that some philosopher has not said it, said Cicero two millennia ago, so perhaps my feeling was mistaken that, for the first time in history, we have reached a stage of absurdity in which a reductio ad absurdum is no longer viable as a rhetorical maneuver, for there is nothing so absurd that everyone recognizes it as such. On the contrary, one man’s absurdity is another man’s possibility or even truth. Nothing can be ruled out without argument.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Street-Corner Semantics”, Taki’s Magazine, 2018-06-30.

December 9, 2022

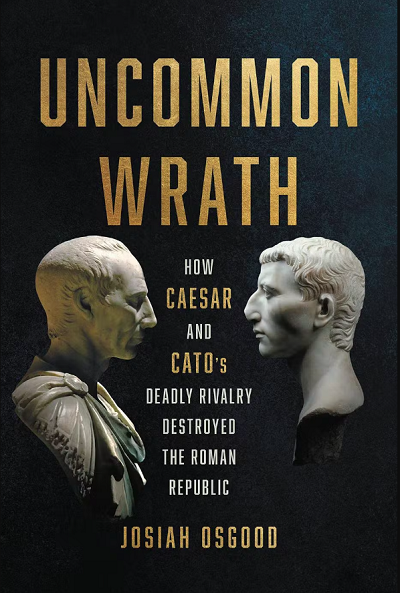

Caesar versus Cato

In The Critic, Daisy Dunn reviews Uncommon Wrath: How Caesar and Cato destroyed the Roman Republic by Josiah Osgood:

If there was one thing the Romans did well — aside from sanitation, irrigation and concrete — it was polemic. Cicero composed fourteen fiery Philippics against Mark Antony in the 40s BC, and Catullus jibed at Julius Caesar so profusely in his poems that he had to issue an apology. Less famous, but equally explosive, was Caesar’s own collection of vitriol. The Anticato survives today only in fragments, but according to an ancient satirist, it was originally so long that it took up two scrolls and almost outweighed the penis of Publius Clodius Pulcher, apparently among the best-endowed politicians in Rome.

Caesar wrote it shortly before he became dictator, with the intention of denigrating the memory of Marcus Porcius Cato, “Cato the Younger”. For years the two men had been locked in furious rivalry. Caesar blasted Cato as cold and miserly. Cato despaired at Caesar’s profligacy and tireless womanising. If Caesar was louche in his barely-belted toga and exotic unguents, Cato was positively austere — a prime hair-shirt candidate — with his bare feet, rustic diet, extreme exercise and strict sexual mores; it was most unusual for a Roman to make his wife the first woman he slept with.

Few would argue with Josiah Osgood, Professor of Classics at Georgetown, when he describes Caesar and Cato as opposites. Even Donald Trump and Joe Biden have more in common than they did. Caesar was the nephew of the wife of Gaius Marius, the populist enemy of Sulla, who as dictator had thousands of Italians proscribed and killed in his bid to restore the authority of the Senate. Cato could count Sulla as an old family friend. Caesar belonged to a well-established Roman family and claimed descent from Venus via her son Aeneas. Cato’s family was Sabine, and his most famous ancestor was a mere mortal in the shape of the plebeian writer and highly conservative statesman Cato the Elder.

The differences between Caesar’s and Cato’s personalities mattered because they reflected the differences in their visions for Rome. Osgood sums these up as “an empire wielding its power for the people” (Caesar) versus “a Senate protecting the people from the all-powerful empire builders” (Cato). It is little wonder they came to blows.

Osgood takes the tense relationship between Cato and Caesar as the central focus of his book. He argues that their feud has been overlooked as a contributing factor to the civil war that erupted in 49 BC and brought the Roman Republic crashing to the ground. Blame for this war has more usually been placed on the collapse of the First Triumvirate — an illegal alliance for power forged between Julius Caesar, Pompey the Great and Marcus Licinius Crassus in 60 BC — and the breakdown in relations between Caesar and Pompey in particular. But all wars have long-term and short-term causes. For Osgood, the dispute between Caesar and Cato was significant in at least the medium term.

August 19, 2022

QotD: How pre-modern polytheistic religions originated

… normally when you ask what the ancients knew of the gods and how they knew it, the immediate thought – quite intuitively – is to go read Greek and Roman philosophers discussing on the nature of man, the gods, the soul and so on. This is a mistake. Many of our religions work that way: they begin with a doctrine, a theory of how the divine works, and then construct ritual and practice with that doctrine as a foundation.

This is exactly backwards for how the ancients, practicing their practical knowledge, learn about the gods. The myths, philosophical discussions and well-written treatises are not the foundation of the religion’s understanding of the gods, but rather the foaming crest at the top of the wave. In practice, the ruminations of those philosophers often had little to do the religion of the populace at large; famously Socrates’ own philosophical take on the gods rather upset quite a lot of Athenians.

Instead of beginning with a theory of the divine and working forwards from that, the ancients begin with proven methods and work backwards from that. For most people, there’s no need to know why things work, only that they work. Essentially, this knowledge is generated by trial and error.

Let’s give an example of how that kind of knowledge forms. Let’s say we are a farming community. It is very important that our crops grow, but the methods and variations in how well they grow are deep and mysterious and we do not fully understand them; clearly that growth is governed by some unseen forces we might seek the aid of. So we put together a ritual – perhaps an offering of a bit of last year’s harvest – to try to get that favor. And then the harvest is great – excellent, we have found a formula that works. So we do it next year, and the year after that.

Sometimes the harvest is good (well performed ritual there) and sometimes it is bad (someone must have made an error), but our community survives. And that very survival becomes the proof of the effectiveness of our ritual. We know it works because we are still here. And I mean survival over generations; our great-great-grandchildren, for whom we are nameless ancestors and to whom our ritual has always been practiced in our village can take solace in the fact that so long as this ritual was performed, the community has never perished. They know it works because they themselves can see the evidence.

(These sorts of justifications are offered in ancient works all the time. Cicero is, in several places, explicit that Roman success must, at the first instance, be attributed to Roman religio – religious scruples. The empire itself serves as the proof of the successful, effective nature of the religion it practices!)

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Practical Polytheism, Part I: Knowledge”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-10-25.

June 9, 2022

QotD: Cicero and the end of the Roman Republic

De legibus (“On the Laws”) along with his earlier work, De re publica (“On the Republic”) show Cicero attempting to grapple with the nature of the Roman Republic and the prospect for reform. In a sense, De re publica looks backwards, with the discussion couched in a fictional dialogue set at the tail end of the life of Scipio Aemilianus (185-129 BC), although Cicero intends the subject – a rumination on the nature of the Republic and its proper workings, based on a discussion of its history – to be applicable in his own time.

De legibus is more aggressively forward looking. Set in Cicero’s own time (it is a dialogue between Cicero, his brother Quintus and their friend Atticus), De legibus first sets out a theory for the general foundation of law […] to use as the basis for a reformed model of the Roman Republic, which is summarized in the third book. Damage to the text means that De legibus cuts off in book three, and there are smaller gaps and fragments in the earlier books as well.

It’s important to get a sense of the situation in the 50s B.C. when Cicero is writing to understand why he feels this is necessary. The previous round of civil wars had ended in 82 B.C., with the victor, the arch-conservative L. Cornelius Sulla, imposing a revised republic with shocking brutality and bloodshed. By the 50s, it would have been clear to anyone paying attention that the peace and apparent stability of the Sullan reforms had been a mirage – the disruptions of the 60s (including the Catilinarian conspiracy, foiled by Cicero) were not one-offs, but merely the first rattlings of the wheels coming off the cart entirely. I don’t want to get too deep into the woods of how exactly this happened; there are any number of good books on the collapse of the Republic which deal with this period (Scullard’s From the Gracchi to Nero (1959) is a venerable and straight-forward narrative of the period; Syme, The Roman Revolution (1939) is probably the most influential – reading both can serve as a foundation for getting into the more recent and often more narrowly directed literature on the topic, note also Flowers, Roman Republics (2011)).

It’s in this context – as the Republic is clearly shaking apart – that Cicero is ruminating on the nature of the Republic, how it functions, what it is for, and how it might be set right. Despite this, Cicero should not be taken for a radical, or even really for much of a reformer; Cicero is a staunch conservative looking to restore the function of the old system, in many cases by a return to tradition as much as the renovation of it. Cicero’s corpus is a plea to save the Republic as it was, not to bury it; it was a plea, of course, that would go unanswered. In a real sense, the Republic died with Cicero.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: A Trip Through Cicero (Natural Law)”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-12-12.