toldinstone

Published 25 Feb 2026How Sparta, the most powerful Greek city-state, collapsed in only 20 years.

0:00 Introduction

0:38 Classical Sparta

1:29 Spartan politics

2:22 Helots

3:24 Population decline

4:37 Hubris

5:25 The Battle of Leuctra

6:42 Messenia liberated

7:35 Enter Macedon

8:08 Attempts at reform

9:08 Irrelevance

9:37 Roman Sparta

(more…)

February 26, 2026

The Decline and Fall of Sparta

February 1, 2026

The Agora of Athens | A Historical Tour

Scenic Routes to the Past

Published 3 Oct 2025The Agora was the political and economic heart of ancient Athens. This tour explores its long history and evocative ruins.

Chapters

0:00 Introduction

0:47 Bouleuterion

1:44 Tholos

2:22 Monument of the Eponymous Heroes

2:56 Temple of Hephaestus

5:28 The Hellenistic Agora

6:16 Stoa of Attalos

6:57 Augustus and the Agora

8:06 Odeon of Agrippa

9:26 Herulian Wall

10:56 Overview

January 11, 2026

QotD: The limits of foreign policy realism

Longtime readers will remember that we’ve actually already talked about “realism” as a school of international relations study before, in the context of our discussion of Europa Universalis. But let’s briefly start out with what we mean when we say IR realism (properly “neo-realism” in its modern form): this is not simply being “realistic” about international politics. “Realism” is amazing branding, but “realists” are not simply claiming that they are observing reality – they have a broader claim about how reality works.

Instead realism is the view that international politics is fundamentally structured by the fact that states seek to maximize their power, act more or less rationally to do so, and are unrestrained by customs or international law. Thus the classic Thucydidean formulation in its most simple terms, “the strong do what they will, the weak suffer what they must”,1 with the additional proviso that, this being the case, all states seek to be as strong as possible.

If you accept those premises, you can chart a fairly consistent analytical vision of interstate activity basically from first principles, describing all sorts of behavior – balancing, coercion, hegemony and so on – that ought to occur in such systems and which does occur in the real world. Naturally, theory being what it is, neo-realist theory (which is what we call the modern post-1979 version of this thinking) is split into its own sub-schools based on exactly how they imagine this all works out, with defensive realism (“states aim to survive”) and offensive realism (“states aim to maximize power”), but we needn’t get into the details.

So when someone says they are a “foreign policy realist”, assuming they know what they’re talking about, they’re not saying they have a realistic vision of international politics, but that they instead believe that the actions of states are governed mostly by the pursuit of power and security, which they pursue mostly rationally, without moral, customary or legal constraint. This is, I must stress, not the only theory of the case (and we’ll get into some limits in a second).

The first problem with IR Realists is that they run into a contradiction between realism as an analytical tool and realism as a set of normative behaviors. Put another way, IR realism runs the risk of conflating “states generally act this way”, with “states should generally act this way”. You can see that specific contradiction manifested grotesquely in John Mearsheimer’s career as of late, where his principle argument is that because a realist perspective suggests that Russia would attack Ukraine that Russia was right to do so and therefore, somehow, the United States should not contest this (despite it being in the United States’ power-maximizing interest to do so). Note the jump from the analytical statement (“Russia was always likely to do this”) to the normative statement (“Russia carries no guilt, this is NATO’s fault, we should not stop this”). The former, of course, can always be true without the latter being necessary.

I should note, this sort of “normative smuggling” in realism is not remotely new: it is exactly how the very first instances of realist political thought are framed. The first expressions of IR realism are in Thucydides, where the Athenians – first at Corinth and then at Melos – make realist arguments expressly to get other states to do something, namely to acquiesce to Athenian Empire. The arguments in both cases are explicitly normative, that Athens did not act “contrary to the common practice of mankind” (expressed in realist dog-eat-dog terms) and so in the first case shouldn’t be punished with war by Sparta and in the latter case, that the Melians should submit to Athenian rule. In both cases, the Athenians are smuggling in a normative statement about what a state should do (in the former case, seemingly against interest!) into a description of what states supposedly always do.

I should note that one of my persistent complaints against international relations study in political science in general is that political scientists often read Thucydides very shallowly, dipping in for the theory and out for the rest. But Thucydides’ reader would not have missed that it is always the Athenians who make the realist arguments and they lost both the arguments [AND] the war. When Thucydides has the Melians caution that the Athenians’ “realist” ruthlessness would mean “your fall would be a signal for the heaviest vengeance and an example for the world to meditate upon”2 the ancient Greek reader knows they are right, in a way that it often seems to me political science students seem to miss.

And there’s a logical contradiction inherent in this sort of normative smuggling, which is that the smuggling is even necessary at all. After all, if states are mostly rational and largely pursue their own interests, loudly insisting that they should do so seems a bit pointless, doesn’t it? Using realism as a way to describe the world or to predict the actions of other states is consistent with the logical system, but using it to persuade other states – or your own state – seems to defeat the purpose. If you believe realism is true, your state and every other is going to act to maximize its power, regardless of what you do or say. If they can do otherwise than there must be some significant space for institutions, customs, morals, norms or simple mistakes and suddenly the air-tight logical framework of realism begins to break down.

That latter vision gives rise to constructivism (“international relations are shaped by ideology and culture”) and IR liberalism (“international relations are also shaped by institutions, which can bend the system away from the endless conflict realism anticipates”). The great irony of realism is that to think that having more realists in power would cause a country to behave in a more realist way is inconsistent with neo-Realism which would suggest countries ought to behave in realist ways even in the absence of realist theory or thinkers.

In practice – and this is the punchline – in my experience most “realists”, intentionally or not, use realism as a cover for strong ideological convictions, typically convictions which are uncomfortable to utter in the highly educated spaces that foreign policy chatter tends to happen. Sometimes those convictions are fairly benign – it is not an accident that there’s a vocal subset of IR-realists with ties to the CATO Institute, for instance. They’re libertarians who think the foreign policy adventures that often flew under the banner of constructivist or liberal internationalist label – that’s where you’d find “spreading democracy will make the world more peaceful” – were really expensive and they really dislike taxes. But “we should just spend a lot less on foreign policy” is a tough sell in the foreign policy space; realism can provide a more intellectually sophisticated gloss to the idea. Sometimes those convictions are less benign; one can’t help but notice the realist pretensions of some figures in the orbit of the current administration have a whiff of authoritarianism or ethnocentrism in them, since a realist framework can be used to drain imperial exploitation and butchery of its moral component, rendering it “just states maximizing their power – and better to be exploiter than exploited”.

One question I find useful to ask of any foreign policy framework, but especially of self-claimed realist frameworks is, “what compromise, what tradeoff does this demand of you?” Strategy, after all, is the art of priorities and that means accepting some things you want are lower priority; in the case of realism which holds that states seek to maximize power, it may mean assigning a high priority to things you do not want the state to do at all but which maximize its power. A realism deserving of the name, in applied practice would be endlessly caveated: “I hate, this but …” “I don’t like this, but …” “I would want to do this, but …” If a neo-realist analysis leads only to comfortable conclusions that someone and their priorities were right everywhere all along, it is simply ideology, wearing realism as a mask. And that is, to be frank, the most common form, as far as I can tell.

That isn’t to say there is nothing to neo-realism or foreign policy realists. I think as an analytical and predict tool, realism is quite valuable. States very often do behave in the way realist theory would suggest they ought, they just don’t always do so and it turns out norms and expectations matter a lot. Not the least of which because, as we’ve noted before, the economic model on which realist and neo-realist thinking was predicted basically no longer exists. To return to the current Ukraine War: is Putin really behaving rationally in a power-maximizing mode by putting his army to the torch capturing burned out Ukrainian farmland one centimeter at a time and no faster? It sure seems like Russian power has been reduced rather than enhanced by this move, even though realists will insist that Russia’s effort to dominate states near it is rational power-maximizing under offensive realism.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday, June 27, 2025 (On the Limits of Realism)”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2025-06-27.

- Thuc. 5.89.

- Thuc. 5.90.

September 23, 2025

Voters didn’t have to pay attention, but now they really, really should

On the social media site formerly known as Twitter, Tristin Hopper posted the best explanations I’ve seen for why Canada is in the state it’s in:

Canadians took it for granted that, no matter which party was in government, the country would continue to be stable, predictable, and competent. That’s clearly wrong today, yet the voters haven’t really accepted the new situation yet. Until they start paying attention, things may not improve.

It’s not just Canada, of course, but Canada is further down the road to ruin and thanks to the governments’ conscious actions, it will probably take longer to recover (and I don’t see a Canadian Javier Milei on the horizon, more’s the pity).

At The Freeman, Will Ogilvie Vega de Seoane discusses a related issue with most forms of representative government:

We are stupid. There, I said it. I feel much better now — like I’ve finally opened up in group therapy. PhDs won’t fix it, nor will subscriptions to all the best outlets. As individuals, we simply do not have the capacity to decide what is best in public life. As voters, we don’t usually care what our representatives are up to, nor do we have the faintest idea what the best policy on agriculture, artificial intelligence, or healthcare should look like — and that’s on a good day. But we do think we know. Deep down we think we are sovereign, that democracy is “all of us”, as though the government were some noble embodiment of “the people” rather than just another collection of organized persons with private agendas.

Plutarch tells a story that I have always found marvelous. It’s about Aristeides “the Just”, one of Athens’s heroes in the Persian Wars. The Athenians, weary of kings and tyrants, invented ostracism — a mechanism to expel for ten years any citizen who got too powerful. Each voter would scratch a name onto a shard of pottery, and if more than 6,000 shards had the same name on them, the man was politely asked to take a decade-long sabbatical. Today we’d probably call it “a career break for the common good”.

Anyway, one day a farmer approached Aristeides himself — without realizing who he was — and asked him to write the name “Aristeides” on his shard. Surprised, Aristeides asked if he had ever harmed him. “No,” said the farmer, “nor do I know him by sight. But I am tired of always hearing him called ‘the Just’.” Aristeides, being annoyingly noble, wrote down his own name and handed the shard back. Later, as he left the city in exile, he prayed the opposite prayer of Achilles: that no crisis should come which would force the Athenians to remember him. On LinkedIn, Aristeides might have written: “Currently on a ten-year sabbatical generously sponsored by the people of Athens. Seeking new challenges outside the Attic peninsula #OpenToWork.”

This, in miniature, is how people vote. Not with knowledge, or vision, or even vague coherence — but out of envy, spite, boredom, or some other glorious irrationality. The Athenians had shards; we have hashtags. Instead of ostracism by pottery, we have ostracism by X: one bad joke, one leaked email, and the digital mob sends you packing. Today in Britain, people can even be jailed for their comments on social media. So much for parrhêsia, that old Athenian virtue of speaking frankly to power. We’ve managed to turn it into a crime — and worse, the canceling mob thinks it’s “speaking truth to power” when in fact it is obedience dressed as rebellion.

Modern voters aren’t any better. Some vote because the candidate owns a cute dog. Others because the candidate is endorsed by Taylor Swift. Entire campaigns have been won on promises of free cable, or by a politician smiling the right way on TikTok. In Spain, we even coined a term for it: the Charo. A Charo is usually an old lady with pink hair who parrots whatever our president says. Charos cannot resist the presidential smile. Even when the president contradicts himself, as he normally does, doing the exact opposite of what he promised, they just blush and blink as if to say: “Oh, Pedro, always misbehaving — we love you all the more for it.” They pamper their charming president and dismiss any criticism as fascist slander. Welcome to the Charocracy.

That’s a pitch-perfect description of the typical Liberal voter in Canada. Mark Carney’s Canada is clearly a maple-flavoured Charocracy.

July 29, 2025

QotD: Thucydides wasn’t articulating a deterministic law of geopolitics – he was writing a tragedy

If you’re 45 and above, you will remember how much fear Japan stoked in the hearts of Wall Street in the 1980s when their economy was booming and their exports sector exploding. There were major concerns that the Japanese economy would leap ahead of the USA’s, and that it would result in Japan discarding its constitutional pacifism in order to spread its wings once more throughout the Pacific.

These concerns were not limited to the fringes, they were real. So real were they that respected geopolitical analysts like George Friedman (later of Stratfor) wrote books like [The Coming War With Japan] The argument was that an upstart like Japan would crash head first into US economic and security interests, sparking another war between the two. This conflict was inevitable because challengers will always seek the crown, and the king will always fight to maintain possession of it.

Suffice it to say that this war did not come to pass. The Japanese threat was vastly overstated, and its economy has been in stagnation-mode for decades now (even though living standards remain very high in relative terms). What may seem inevitable need not be.

The next several years will see marked increase in tension between the USA and China, as the former completes its long awaited “Pivot to East Asia”. So anxious are the Americans to pivot that they have been threatening to “walk away” from Ukraine if they cannot hammer down a peace deal in the very near future. This indicates just how serious a threat they view China’s ascent to be to its economic and security interests. If they are willing to sacrifice more in Ukraine than originally intended, the implication is that China’s rise is a grave concern, and that a clash between the two looks very likely … some would argue that it is inevitable, appealing to a relatively new IR concept called the “Thucydides Trap“.

Andrew Latham explains the concept to us, arguing that Thucydides is misunderstood, making conflict between rising powers and hegemons not necessarily inevitable:

The so-called Thucydides Trap has become a staple of foreign policy commentary over the past decade or so, regularly invoked to frame the escalating rivalry between the United States and China.

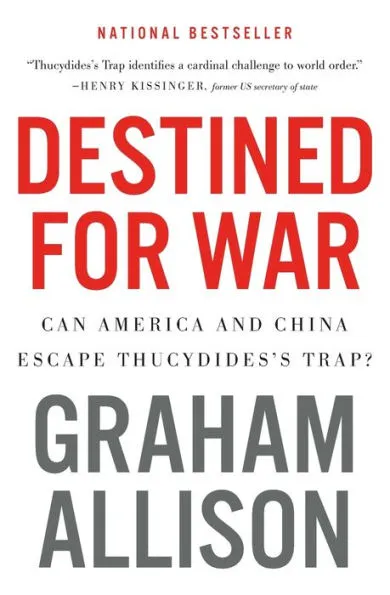

Coined by political scientist Graham Allison — first in a 2012 Financial Times article and later developed in his 2017 book Destined for War — the phrase refers to a line from the ancient Greek historian Thucydides, who wrote in his History of the Peloponnesian War, “It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.”

Distortion:

At first glance, this provides a compelling and conveniently packaged analogy: Rising powers provoke anxiety in established ones, leading to conflict. In today’s context, the implication seems clear – China’s rise is bound to provoke a collision with the United States, just as Athens once did with Sparta.

But this framing risks flattening the complexity of Thucydides’ work and distorting its deeper philosophical message. Thucydides wasn’t articulating a deterministic law of geopolitics. He was writing a tragedy.

This essay might be an exercise in historical sperging, but I think it has value:

Thucydides fought in the Peloponnesian War on the Athenian side. His world was steeped in the sensibilities of Greek tragedy, and his historical narrative carries that imprint throughout. His work is not a treatise on structural inevitability but an exploration of how human frailty, political misjudgment and moral decay can combine to unleash catastrophe.

That tragic sensibility matters. Where modern analysts often search for predictive patterns and system-level explanations, Thucydides drew attention to the role of choice, perception and emotion.

His history is filled with the corrosive effects of fear, the seductions of ambition, the failures of leadership and the tragic unraveling of judgment. This is a study in hubris and nemesis, not structural determinism.

Much of this is lost when the phrase “Thucydides Trap” is elevated into a kind of quasi-law of international politics. It becomes shorthand for inevitability: power rises, fear responds, war follows.

Therefore, more of a psychological study of characters rather than structural determinism.

Giving credit to Allison:

Even Allison, to his credit, never claimed the “trap” was inescapable. His core argument was that war is likely but not inevitable when a rising power challenges a dominant one. In fact, much of Allison’s writing serves as a warning to break from the pattern, not to resign oneself to it.

Misuse:

In that sense, the “Thucydides Trap” has been misused by commentators and policymakers alike. Some treat it as confirmation that war is baked into the structure of power transitions — an excuse to raise defense budgets or to talk tough with Beijing — when in fact, it ought to provoke reflection and restraint.

To read Thucydides carefully is to see that the Peloponnesian War was not solely about a shifting balance of power. It was also about pride, misjudgment and the failure to lead wisely.

Consider his famous observation, “Ignorance is bold and knowledge reserved”. This isn’t a structural insight — it’s a human one. It’s aimed squarely at those who mistake impulse for strategy and swagger for strength.

Or take his chilling formulation, “The strong do what they will and the weak suffer what they must”. That’s not an endorsement of realpolitik. It’s a tragic lament on what happens when power becomes unaccountable and justice is cast aside.

and

In today’s context, invoking the Thucydides Trap as a justification for confrontation with China may do more harm than good. It reinforces the notion that conflict is already on the rails and cannot be stopped.

But if there is a lesson in The History of the Peloponnesian War, it is not that war is inevitable but that it becomes likely when the space for prudence and reflection collapses under the weight of fear and pride.

Thucydides offers not a theory of international politics but a warning — an admonition to leaders who, gripped by their own narratives, drive their nations over a cliff.

Latham does have a point, but events have a momentum all their own, and they are often hard to stop. Inevitabilities do exist, such as Israel and Hezbollah entering into conflict with one another in 2022 after their 2006 war saw the latter come out with a tactical victory. Barring a black swan event, the USA and China are headed for a collision. The question is: in what form?

Niccolo Soldo, “Saturday Commentary and Review #188 (Easter Monday Edition)”, Fisted by Foucault, 2025-04-21.

March 3, 2025

All The Basics About XENOPHON

MoAn Inc.

Published 7 Nov 2024I actually found this video really tricky considering I want to go into the texts of Xenophon and if I told you everything about the march of the ten thousand then I would have just told you the whole Anabasis?? Which defeats the whole purpose of an introductory video?? So I PROMISE more clarity will come in future videos as Xenophon himself breaks down his journey home from Persia and why they were there in the first place. Therefore, you have ALL OF THAT to look forward to — coming soon!!!

(more…)

February 6, 2025

Historian Answers Google’s Most Popular Questions About Ancient Greek Warfare

History Hit

Published 2 Oct 2024Was the Trojan War real? Did the Greeks dig ditches? Why did the Greeks fight the Persians?

Ancient Greek historian Roel Konijnendijk Answers Google’s Most Popular Questions About Ancient Greek Warfare.

00:00 Intro

00:46 Who did the Greeks fight?

01:47 How did the Greeks fight?

02:59 What weapons did the Greeks fight with?

04:25 Did the Greeks fight on chariots?

05:08 Did the Greeks have cavalries?

06:51 Did the Greeks have navies?

08:24 Did the Greeks do sieges?

09:46 Did the Greeks dig ditches?

10:47 Who was the best Greek warrior?

12:05 Was the Trojan War real?

14:04 Who started the trojan war?

15:34 Who was Helen of troy?

16:15 Did the gods fight in the trojan war?

17:02 Which heroes fought in the trojan war?

18:21 What was the trojan horse?

19:16 Who won the trojan war?

20:20 Why was the Trojan war important?

21:28 Why did the Greeks fight the Persians?

23:09 Where was the Persian war?

24:59 Who won the Persian war?

26:50 Why was the Persian war important?

28:26 Did the Spartans fight the Athenians?

28:58 Why was it called the Peloponnesian war?

29:50 Who won the Peloponnesian war?

31:51 What happened after the Peloponnesian war?

(more…)

January 13, 2025

The “Thucydides Trap”

At History Does You, Secretary of Defense Rock provides a handy explanation of the term “the Thucydides Trap”:

In the world of international relations, few concepts have captured as much attention — and sparked as much debate — as the “Thucydides Trap”. Brought to prominence by Harvard political scientist Graham Allison, the term suggests that conflict is almost inevitable when a rising power threatens to displace an established one, a dynamic often invoked to frame the strategic rivalry between the United States and China. Lauded as a National Bestseller and praised by figures like Henry Kissinger and Joe Biden, Allison’s Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? has become a staple of policy discussions and academic syllabi. Yet beneath the widespread acclaim lies a deeply flawed analysis, one that risks oversimplifying history and perpetuating a fatalistic narrative that could shape policy in dangerous ways. Far from an inescapable destiny, the lessons of history and the nuances of modern geopolitics suggest that the so-called “trap” may be more myth than inevitability.

The term “Thucydides Trap” is derived from a passage in the ancient Greek historian Thucydides’ work History of the Peloponnesian War, where he explained the causes of the conflict between Athens (the rising power) and Sparta (the ruling power) in the 4th century BC. Thucydides famously wrote

It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.

Allison defines the “Thucydides Trap” as “the severe structural stress caused when a rising power threatens to upend a ruling one”.1 More articles by Allison using this term previously appeared in Foreign Policy and The Atlantic. The book, published in 2017, was a huge hit, being named a notable book of the year by the New York Times and Financial Times while also receiving widespread bipartisan acclaim from current and past policymakers. Historian Niall Ferguson described it as a “must-read in Washington and Beijing”.2 Senator Sam Nunn wrote, “If any book can stop a World War, it is this one”.3 A brief search on Google Scholar reveals the term “Thucydides Trap” has been cited or used nearly 19,000 times. In 2015, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull even publicly urged President Xi and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang to avoid “falling into the Thucydides Trap”.4 One analyst observed that the term had become the “new cachet as a sage of U.S.-China relations”.5 The term has become so prominent that it is almost guaranteed to appear in any introductory international politics course when discussing U.S.-China relations.

Allison wrote in his essay “The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?” in The Atlantic published in 2015, “On the current trajectory, war between the United States and China in the decades ahead is not just possible, but much more likely than recognized at the moment” forewarning, “judging by the historical record, war is more likely than not”.6 A straightforward analysis of the 16 cases in the book and previous essays might indicate that, based on historical precedent, there is approximately a 75 percent likelihood of the United States and China engaging in war within the next several decades. Adding the additional cases from the Thucydides Trap Website would still leave a 66 percent chance, more likely than not, that two nuclear-armed superpowers will go to war with one another, a horrifying and unprecedented proposition.7

With such alarm, it’s no surprise that the concept gained such widespread attention. The term is simple to understand and in under 300 pages, Allison delivers a sweeping historical narrative, drawing striking parallels between events from ancient Greece to the present day.8 International Relations as a field often struggles to break through in the public discourse, but Destined for War broke through, making a broad impact on academic and popular discourse.

1. Graham Allison, Destined For War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017), 29.

2. Ibid., iii.

3. Ibid., vi.

4. Quoted by Alan Greeley Misenheimer, Thucydides’ Other “Traps”: The United States, China, and the Prospect of “Inevitable” War (Washington: National Defense University, 2019), 8.

5. Misenheiemer, 1.

6. “Thucydides’s Trap Case File” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, accessed December 31, 2024

7. Graham Allison, “The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?” The Atlantic, September 24, 2015.

8. Misenheimer details what Thucydides actually said about the origins of the Peloponnesian War, 10-17.

The Writings of Cicero – Cicero and the Power of the Spoken Word

seangabb

Published 25 Aug 2024This lecture is taken from a course I delivered in July 2024 on the Life and Writings of Cicero. It covers these topics:

• Introduction – 00:00:00

• The Deficiencies of Modern Oratory – 00:01:20

• The Greeks and Oratory – 00:06:38

• Athens: Government by Lottery and Referendum – 00:08:10

• The Power of the Greek Language – 00:17:41

• The General Illiteracy of the Ancients – 00:21:06

• Greek Oratory: Lysias, Gorgias, Demosthenes – 00:28:38

• Macaulay as Speaker – 00:34:44

• Attic and Asianic Oratory – 00:36:56

• The Greek Conquest of Rome – 00:39:26

• Roman Oratory – 00:43:23

• Cicero: Early Life – 00:43:23

• Cicero in Greece – 00:46:03

• Cicero: Early Legal Career – 00:46:03

• Cicero: Defence of Roscius – 00:47:49

• Cicero as Orator (Sean Reads Latin) – 00:54:45

• Government of the Roman Empire – 01:01:16

• The Government of Sicily – 01:03:58

• Verres in Sicily – 01:06:54

• The Prosecution of Verres – 01:11:20

• Reading List – 01:24:28

(more…)

November 18, 2024

Changing the way “our leaders” speak to us

Ted Gioia says that the old rules of communicating to the public are undergoing a major shift.

Before they executed Socrates in the year 399 BC — on charges of impiety and corrupting youth — the philosopher was given a chance to defend himself before a jury.

Socrates started his defense with an unusual plea.

He told his listeners that he had no skill at making speeches. He just knew the everyday language of the common people.

Socrates explained that he had never studied rhetoric or oratory. He feared that he would embarrass himself by speaking so plainly in his trial defense.

“I show myself to be not in the least a clever speaker,” Socrates told the jurors, “unless indeed they call him a clever speaker who speaks the truth.”

He knew that others in his situation would give “speeches finely tricked out with words and phrases”. But Socrates only knew how to use “the same words with which I have been accustomed to speak” in the marketplace of Athens.

Socrates wasn’t exaggerating. His entire reputation was built on conversation. He never wrote a book — or anything else, as far as we can tell.

Spontaneous talking was the basis of his famous “Socratic method” — a simple back-and-forth dialogue. You might say it was the podcasting of its day. He aimed to speak plainly — seeking the truth through open and unfiltered conversation.

That might get you elected President in the year 2024. But it didn’t work very well in Athens, circa 400 BC.

Socrates received the death penalty — and was executed by poisoning.

Is that shocking? Not really.

Western culture was built on one-way communication. Leaders and experts speak — and the rest of us listen.

Socrates was the last major thinker to rely solely on conversation. After his death, his successors wrote books and gave lectures.

That’s what powerful people do. They make decisions. They give orders. They deliver speeches.

But not anymore.

In the aftermath of the election, the new wisdom is that giving speeches from a teleprompter doesn’t work in today’s culture. Citizens want their leaders to sit down and talk.

And not just in politics. You may have seen the same thing in your workplace — or in classrooms and other group settings. People now resist one-way orders from the top.

The word “scripted” is now an insult. Plainspoken dialogue is considered more trustworthy. This is part of the up-versus-down revolution I’ve written about elsewhere — a conflict that, I believe, may have even more impact on society than Left-versus-Right.

For better or worse, the hierarchies we’ve inherited from the past are toppling. To some extent, they are even reversing.

This is now impacting how leaders are expected to speak. Events of the last few days have raised awareness of this to a new level — but the “experts” should have expected it. That’s especially true because the experts will be those most impacted by this shift.

October 12, 2024

Classics Summarized: The Oresteia

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published Jul 19, 2017Nobody look at how long ago I promised to do this.

That’s right! The sequel to Iphigenia, which itself was a prequel to the Iliad, has finally been given the ol’ OSP treatment! And it only took me TWO AND A HALF YEARS

(more…)

September 25, 2024

The Life and Times of Xerxes

seangabb

Published Jun 10, 2024An occasional lecture for our Classics Week, this was given to provide historical background for a lecture from the Music Department on Handel’s opera “Serse” (1738).

Books by Sean Gabb: https://www.amazon.co.uk/kindle-dbs/e…

His historical novels (under the pen name “Richard Blake”): https://www.amazon.co.uk/Richard-Blak…

If you have enjoyed this lecture, its author might enjoy a bag of coffee, or some other small token of esteem: https://www.amazon.co.uk/hz/wishlist/…

August 13, 2024

QotD: The weird world of the Iliad

[Jane Psmith:] … as weird and crufty and full of archaism as it is, the Iliad is actually the first step in the rationalization of the ancient world. Like, it’s even weirder before.

Homer (“Homer“) presents the gods as having unified identities, desires, and attributes, which of course you have to have in order to have any kind of coherent story but which is not at all the way the Greeks understood their gods before him (or even mostly after). The Greeks didn’t have a priestly caste with hereditary knowledge, or Vedas, or anything like that, so their religion is even more chaotic than most primitive religions. “The god” is a combination of the local cult with its rituals, the name, the myths, and the cultic image, and these could (and often did) spread separately from one another. The goddess with attributes reminiscent of the ancient Near Eastern “Potnia Theron” figure is Hera, Artemis, Aphrodite, Demeter, or Athena, depending on where you are. Aphrodite is born from the severed testicles of Ouranos but is also the daughter of Zeus and Dione. “Zeus” is the god worshipped with human sacrifice on an ash altar at Mt. Lykaion but also the god of the Bouphonia but also a chthonic snake deity. Eventually these all get linked together, much later, primarily by Homer and Hesiod, but even after the stories are codified — okay, this is the king of the gods, he’s got these kids and this shrewish wife, he’s mostly a weather deity — the ritual substrate remains. We still murder the ox and then try the axe for the crime, which has absolutely nothing to do with celestial kingship but it’s what you do. If you’re Athenian. Somewhere else they do something completely different.

I also really enjoyed this book, and I think for similar reasons to you. Because you’re right, at the end of the classical world it wasn’t just the philosophers. One major theme in Athenian drama is the conscious attempt to impose rationality/democracy/citizenship/freedom (all tied together in the Greek imagination) in place of the bloody, chthonic, archaic world of heredity.1 It’s an attempt at a transition, and one which gets a lot of attention I think in part because people read the Enlightenment back into it. But my favorite part of the The Ancient City is Fustel de Coulanges’s exploration of the other end of the process: where did all the weird inherited ritual came from in the first place?!

The short version of the answer is “the heroön“. Or as he puts it: “According to the oldest belief of the Italians and Greeks, the soul did not go into a foreign world to pass its second existence; it remained near men, and continued to live underground.” Everything else follows from here: the tomb is required to confine the dead man, the burial rituals are to please him and bind him to the place, the grave goods and regular libations are for his use, and he is the object of prayers. Fustel de Coulanges is incredibly well-read (that one sentence I quoted above cites Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations, “sub terra censebant reliquam vitam agi mortuorum“, plus Euripides’ Alcestis and Hecuba), and he references plenty of Vedic and later Hindu texts and practices too. I also immediately thought of the Rus’ funeral described by ibn Fadlan and retold in every single book about the Vikings, in which, after all the exciting sex and human sacrifice is over, the dead man’s nearest kinsman circles the funerary ship naked with his face carefully averted from it and his free hand covering his anus. This seems like precautions: there’s something in the ship-pyre that might be able, until the rites are completed, to get out.2 And obviously we now recognize tombs and burial as being very important to the common ancestors of the classical and Vedic worlds — from Marija Gimbutas’s kurgan hypothesis to the identification of the Proto-Indo-Europeans with the Yamnaya culture (Ямная = pit, as in pit-grave) — their funerary practices have always been core to how we understand them. But I’m really curious how any of this would have worked, practically, for pastoral nomads! Fustel de Coulanges makes it sound like you have your ancestor’s tomb in your back yard, more or less, which obviously isn’t entirely accurate when you’re rolling around the steppe in your wagon.

I’d also be interested to see an archeological perspective on his next section, about the sacred hearth. This is the precursor of Vesta/Hestia and also Vedic Agni, the reconstructed *H₁n̥gʷnis (fire as animating entity and active force) as opposed to *péh₂ur (fire as naturally occurring substance). I looked back through my copy of The Wheel, the Horse, and Language and (aside from a passing suggestion that the hearth-spirit’s genderswap might be due to the western Yamnaya’s generally having more female-inclusive ritual practices, possibly from the influence of the neighboring Tripolye culture), I didn’t find anything. I suppose this makes sense — you can’t really differentiate between the material remains of a ritual hearth and a “we’re cold and hungry” hearth, especially if people are also cooking on the ritual hearth so there’s not a clear division anyway. But if anyone has done it I’d like to see.

I don’t know enough of the historiography to know whether Fustel de Coulanges was saying something novel or contentious in the mid-19th century, but he seems to be basically in line with more recent scholarship even if he’s not trendy. But The Ancient City can be read as a work of political philosophy as well as ancient history!

Jane and John Psmith, “JOINT REVIEW: The Ancient City, by Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-02-20.

1. And of course that tension is extra intriguing because the dramas are always performed at one of these inherited rituals, in this case the city-wide Great Dionysia festival, although it was a relatively late addition to the ritual calendar. Incidentally it’s way less bizarre than the Attic “rustic” Dionysia which is all goat sacrifices and phallus processions. (There’s also the Agrionia in Boeotia which is about dissolution and inversion and nighttime madness, and another example of “the god” being a rather fluid concept.)

2. Neil Price, in his excellent Children of Ash and Elm, says that the archaeological evidence seems to confirm this:

“Most of the objects [in the Oseberg ship burial] were deposited with great care and attention, but at the very end most of the larger wooden items — the wagons, sleds, and so on — were literally thrown onto the foredeck, beautiful things just heaved over the side from ground level and being damaged in the process. The accessible end of the burial chamber was then sealed shut by hammering planks across the open gable, but using any old piece of wood that seems to have been at hand. The planks were just laid across at random — anything to fill the opening into the chamber where the dead lay. The nails were hammered in so fast one can see where the workers missed, denting the wood and bending or breaking off the nail heads.”

August 10, 2024

History Summarized: Athens (Accidentally) Invents Democracy

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published Apr 26, 2024“TOP FIVE Athenian Tyrants – #2 will surprise you and #3 will get murdered in a polycule-gone-wrong!”

-Herodotus if he had a blog.SOURCES & Further Reading:

“Revolution & Tyranny” & “The Origins of Democracy” from Ancient Greek Civilization by Jeremy McInerney

Athens: City of Wisdom by Bruce Clark, 2022

The Greeks: A Global History by Roderick Beaton, 2021

The Greeks: An Illustrated History by Diane Cline, 2016

I also have a university degree in Classical Civilization.

(more…)

July 23, 2024

Why Most “Ancient” Buildings are Fakes

toldinstone

Published Apr 12, 2024Almost every ancient monument has been at least partially reconstructed, for a wide range of reasons …

Chapters:

0:00 Introduction

1:06 The Forum and Colosseum

2:27 The Ara Pacis

3:24 Early restorations

4:37 Mondly

5:47 Roman forts and baths

6:42 Knossos

7:23 The Stoa of Attalus

8:59 The Acropolis

10:05 When to restore?

(more…)