Not Just Bikes

Published 6 Oct 2024Chapters

0:00 Intro

1:24 Leaving New York

3:04 On the train

4:03 The views

4:38 Freight trains & delays

5:37 The train is so much more comfortable

7:09 The border crossing

8:17 The Canadian side

9:24 Should you take this train?

10:20 Comparisons to Europe & Japan

11:20 We need more high-speed rail

12:02 VIA Rail is bad … and getting worse

12:58 VIA Rail is expensive!

14:11 The new VIA Rail baggage policy

15:49 Better train service is important!

17:14 Concluding thoughts

(more…)

January 31, 2025

I Spent Over 12 Hours on an Amtrak Train (on purpose)

July 31, 2024

QotD: Train nostalgia

Nothing compares to arriving by train; you’re not dropped off in a climate-controlled center on the edge of town, but dropped in the humid middle, surrounded by machinery and steam and shouts and clangs. You don’t slide up the jetway — you schlep yourself along the platform to the stairs, you jostle and maneuver and find your place in the throng; you thread through the station, head outside — and oh, my, GOD, there it is, loud and wide and high and alive, the city.

When you leave you leave with the nudge. Planes waddle to the runway then throw themselves in the air with theatrical fury. Trains nudge you out. You’re sitting in your seat; you’re still. The strange orange subterranean light fills the car; again the shouts, the clangs, the whistles, the whirr of electric carts. The doors huff shut. Conductors walk around listening to crackly voices on the walkie-talkie. You wait. Then the nudge. The train lurches forward, the wheels clank, the rhythm begins, and you’re on your way. In a few minutes you’ll clear the tunnels and see the city from below, indifferent to your departure. Clank clank clank clank clank clank clank clank. On the plane you seem to approach New York like a nest of hornets — you’re wary, circling, then you bore in. When you leave by train you simply move along, move down, move out. Old tunnels, old concrete, rusted remains, barrels, trash, then light. Then the tunnel that takes you away. Standing in Times Square it seems a hard place to leave; it seems like you’d have to fight your way past the lights and noise and commotion and crowds. You’re almost surprised when you leave with such ease, such lack of contention. There should have been a brass band, or a mob.

Manhattan seems like a dream by the time you’re 30 minute down the rails. Maybe that’s why I keep going back. You’re kidding me. This is real? Gowan.

James Lileks, The Bleat, 2005-07-20.

July 15, 2024

From Utica to Chicago, then on to New Orleans

A.M. Hickman takes Amtrak on a pre-wedding rail tour of the United States. We pick up the narrative in Utica, New York, whose Amtrak station apparently gives off a North Korean/Potemkin village vibe:

The gargantuan marble-columned Utica train station sleeps like silver spoons in a dusty drawer of a great house. The bones of Utica have the smell and patina of old finery laid out at an estate sale in a great and crumbling chateau; its patrons long dead or doddering — if one walks quietly, they can hear their ghosts. I sip a porter at the trackside pub, staring out into the maze of empty streets as the pub’s speakers play the song “Allstar”, an upbeat tune released in 1999 by the one-hit-wonder band Smashmouth. And the barkeep looks as if the year 1999 never ended; cigarette smoke curling around his blonde frosted tip hairdo, leaning against the brick walls of the tavern’s courtyard in his sunglasses and FUBU-brand track jacket, kicking at the dirt in his stained white Reeboks.

No one else is at the bar — one wonders if Utica is being maintained in North Korean style, subsidized by the state to keep up appearances, spray-painted to the “uncanny valley” hue of sham vitality lest a train passenger should step off for a smoke break and start asking too many questions. I ponder this as the song continues — “Hey now, you’re an All-star, get your game on on, go play // hey now, you’re a rockstar, get the show on, get paid …” The barkeep ashes his cigarette and glowers, casting furtive glances toward the empty bar. I pay the tab, glad to be departing this weird, empty place in the heart of American Pyongyang — where one gets the disturbing sense that they may be being watched.

The train arrives, and Keturah is with me. If Amtrak’s Lake Shore Limited were one’s first introduction to the Amtrak system they might get the impression that it’s a long, metal, track-bound Greyhound bus. The passengers are sullen and bored with earbuds universally donned. Cheerio dust covers our seat, and a heavy-set hustler-looking character in an Eminem t-shirt is sawing wood, snoring deeply, displaying all of the textbook symptoms of undiagnosed sleep apnea. Worst of all, the train’s bright white lights — the sorts of fluorescent lights one sees inside of hospitals and Wal-Marts — stay on all night, angled directly into our eyes, and we fitfully sleep as the train rattles at 110mph all the way to Chicago. The trip takes fifteen hours.

For Keturah and I, this ride is our last bit of time together before separating for a month. We’d both been taken with the romantic idea of parting ways for a few weeks before our wedding — and at Chicago, she’d head to southern Illinois to see her great-grandmother, and I’d jump aboard the City of New Orleans train to soak in the sinful humidity of the Crescent City. From there, I’d run a nearly 8,000-mile circuit around the United States — and if the trains ran on time, I’d arrive at our wedding in Upstate New York on time. Sleepy-eyed and rueing our separation, I saw her off onto her train.

I wandered Chicago’s Union Station alone, rattled by the gravity of her absence already, and several hours later, I hopped onto my own southbound train, dreaming of the woman who would become my wife.

A “vibe shift” takes place as I step aboard The City of New Orleans. The workers are a jazzy bunch, obviously natives of the city below sea level, all of them jocular and energetic; smooth Louisiana tones drip from their smiling craws — “good evening baby, we don’t mind you playing music in the cafe car — but if it’s the nighttime hours it had bettuh be smooth!”

Unlike the Lake Shore Limited, this train is equipped with a “Superliner” viewer car with domed glass windows that afford passengers views of the scenery. Most long-distance routes are equipped with these — except the routes that go in and out of New York City, as the train tunnels there don’t have the clearance for these tall double-decker cars. But the view of the scenery doesn’t matter much on the ride south through Illinois and Mississippi. This stretch of track is, in the colorful words of one especially talkative train attendant, “a damned old tunnel of green trees and shit“. Nonetheless this “tunnel” had a soothing effect as we sped southward, and I crawled down under the Superliner’s benches to sleep.

In New Orleans, I had the great pleasure of staying with one C. Sandbatch, a native son of New Orleans, and Covington, and Mississippi, and Kentucky, and, well — practically every location in the American South but Alabama or Georgia. A polymath of Southern geography, history, and literature, Mr. Sandbatch quite naturally opened his home to me, offering the air mattress in his high-ceilinged back room as organically as the forest offers its glens and creek-beds to a transient jackrabbit or wren. And quite naturally, he stationed himself upon the porch of his sparsely-decorated shotgun shack house, musing on his weirder years, relating tales of corrupt Parish Presidents and bayou dramas, and offering reflections on the more nuanced elements of Deep South race relations, New Orleans musical genre-bending, and Southern ecology.

Leaning back onto the wood of the old porch — which had been under some eleven feet of water during Hurricane Katrina — I listened to him speak in slow, eloquent tones as the breeze rustled the palms on the street. His cigarette smoke hung above the sleepy-eyed cats, and the wine in my cup was lukewarm in the humidity. We drove all over the city in his ailing old jeep, a vehicle whose transmission had the habit of “burping” in traffic, and we flitted in and out of cafes and bars, each of which seemed to be a sort of checkpoint in Mr. Sandbatch’s memory. Wistfully he drank as he spoke, and I felt myself slipping into the ease one knows only when wandering a city with one of its own sons.

January 29, 2024

QotD: Amtrak’s improvements

Amtrak has improved its service since I last rode the rails, and you no longer fear that the lavatories will be occupied by giant hissing Madagascar cockroaches that climbed up the pipes the last time the train slowed down. The food’s good, and the service is cheerful — unlike the servers of old, who might as well have begun the meal by announcing “Ladies and gentlemen, I have a virtual guarantee of lifetime employment, and as you might expect that’s going to affect my interest in prompt and friendly service. Affect it severely. Now you’re all going to have the lasagna. It was made during the Carter era. The only thing older than the lasagna is the beer. And it’s also warmer.”

No, Amtrak is in good shape. The cars have been rebuilt, the blankets no longer draw blood when they come in contact with human skin, the tracks are smoother, and the Pit of Hazy Death — the snack car — is now smoke-free.

That means it’s not packed with throaty-voiced semi-toothed drifters who emit a Pompeii-sized cloud of ash every time they start in on one of those up-from-the-ankles 20-minute hacking fits. And somehow — don’t ask me how — the general aromatic profile of the train is no longer “feet, with a top note of septic tank.” The train actually smelled good. Bravo, Amtrak.

James Lileks, “A windy narrative of a trip to Chicago”, Minneapolis Star-Tribune, 2004-12-19.

August 5, 2023

The rotten luck of the American Orient Express

Train of Thought

Published 5 May 2023In today’s video, we take a look at the American Orient Express, an attempt made by several businesses to replicate the charm and appeal of the real deal that just kept running into bad luck.

(more…)

March 20, 2022

Florida’s new passenger rail service

Thomas Walker-Werth contrasts the different experiences of California and Florida in trying to build new passenger railway services:

When the Federal Government ordered the construction of the Interstate Highway System in the 1950s and 1960s (at a cost to taxpayers of roughly $580 billion in 2022 dollars), it all but killed America’s privately operated passenger railroads. Since then, rail travel in America has mostly consisted of government-subsidized Amtrak services of deteriorating quality that amble across the country, catering to a niche market of leisure travelers and those with no other options. On the busy Northeast Corridor between Boston and Washington D.C. there is still enough demand to operate a busy, profitable service, but elsewhere Amtrak’s services are too slow, inconvenient, and infrequent to effectively compete with highways and airlines.

But with gas prices rising and traffic congestion strangling many American cities, passengers, investors, and government planners are all reconsidering railroads. Several new projects have sprung up across the country, aiming to link major cities a few hundred miles apart, where a train might provide a more convenient journey than a plane, car, or bus. Some of these projects are led by state governments, others by private companies. The contrast between the two is dramatic. To illuminate that difference, compare the government-run California High Speed Rail project with Brightline, a new private rail system in Florida.

Approved in 2008, California High Speed Rail (CHSR) was expected to deliver a 520-mile two-track, electrified high-speed railway on an all-new route between Los Angeles and San Francisco by 2029. Fourteen years later, CHSR is now only expected to have a 171-mile single-track section between Madera and Bakersfield will be operational by 2030. Meanwhile the project’s cost has ballooned to $80 billion from an original budget of $33 billion, and costs are expected to rise further to $100 billion, or triple the original budget.

Meanwhile in Florida, a very different kind of passenger railroad is already up and running. Brightline was launched in 2012 by the Florida East Coast Railway, a private freight railroad. Unlike CHSR, Brightline mostly uses existing routes, removing the need to acquire (or appropriate) large amounts of land. Instead of building the whole line before beginning any passenger services (as CHSR is doing), Brightline began construction on a 70-mile section from Miami to West Palm Beach in 2014 and opened it to passengers in 2018. This meant that Brightline already had an operational, revenue-producing service before embarking on the 170-mile northward extension to Orlando Airport. That extension is expected to open in 2023, and the entire project will cost about $1.75 billion, raised through private financing.

This equates to about $7.3 million per mile for Brightline, compared to $153.8 million per mile for CHSR (using the current $80 billion budget). Why will CHSR cost at least twenty times more per mile than Brightline? How has Brightline managed to deliver a high-speed intercity passenger rail system within ten years whereas CHSR needs twenty-two years to deliver an incomplete, scaled-down version of its original plan? Much of the answer comes down to the fundamental nature of public works projects such as CHSR.

This isn’t quite a fair apples-to-apples comparison between Brightline and CHSR, as Brightline’s services will have to interact with freight trains on conventional rails while CHSR — if ever completed — will be a separate line hosting only CHSR’s own high-speed passenger trains. Brightline’s trains will probably not have the theoretical top speed that CHSR is intended to use, as the physical plant of rail lines intended for mixed-use traffic will limit the speeds due to signalling, traffic density and braking distances of the respective types of trains.

May 27, 2020

American passenger trains before Amtrak

George Hamlin reflects on the state of the US passenger rail system before the formation of Amtrak in 1971:

… non-commuter U.S. passenger trains can be said to have been under siege essentially for my entire lifetime, beginning not long after the end of World War II. Many railroads spent large sums to re-equip with streamlined lightweight equipment after the war, only to see what was originally couched as an investment turn into essentially a drain on their companies’ treasuries.

And the “rewards” for this? Passengers decamped to the rapidly-expanding airlines, and their personal automobiles. The decisive blow came in 1956, with the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act, which led to the Interstate Highway System.

Quoting from Joe Welsh’s Pennsy Streamliners, The Blue Ribbon Fleet (page 138), “Referring to the challenge, [PRR President] Symes wrote ‘There is such a thing as planning an orderly retreat in the face of superior forces.’ Clearly, the bugle had been sounded.”

In 1958, an Interstate Commerce Commission Hearing Examiner predicted that there would be no intercity passenger trains by 1970; he only missed by four months, effectively (and didn’t count on the Southern Railway, Rio Grande and Rock Island shying away from the government’s largesse). In 1959, TRAINS magazine devoted an entire issue to what was now clearly a crisis; the cover bore the legend “Who Shot the Passenger Train?”, complete with simulated bullet hole.

The 1960s in the U.S. could well be described as the “train-off” decade from a transportation history perspective; get, and read, Fred Frailey’s Twilight of the Great Trains, for a blow-by-blow analysis. The 1970s quickly produced the Penn Central bankruptcy, which proved to be the catalyst for government intervention; less than a year later, Amtrak was on the scene.

And since, it has frequently found itself in a “Perils of Pauline” existence, ranging from lack of funding to buy equipment, in many cases, to several bouts of route eliminations, to micro-management by politicians that don’t seem to be willing to provide consistent operational funding so that the company can make reasonable plans.

December 28, 2019

American railways are simultaneously world-beating and terrible

That’s because, as Sean Smith and Peter Earle point out, there are two very different entities running on America’s rails:

Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) locomotive 5399, Kansas City Southern (KCS) 4807, and 1890 westbound on the BNSF Emporia Sub near Timberland Blvd West of Northgate Street in Olathe, Kansas.

Photo by Tyler Silvest via Wikimedia Commons.

American railways are the envy of the world.

Many might shake a collective head at that statement. In the case of passenger rail that is an appropriate reaction. Since it was pieced together – a government-constructed Franken-rail system built of numerous bankrupt railways which were essentially nationalized – Amtrak has been a reliable money sink, losing tens of billions of dollars since 1970.

Any traveler that has used Amtrak to any significant extent has firsthand experience with the crumbling infrastructure, frequent delays, and general unpleasantness that accompanies U.S. passenger rail service. Even the oft-cited bright spot of Amtrak, the “high speed” Acela system (which shuttles between Boston and Washington D.C) pales in comparison when compared to high-end passenger rail systems in Western Europe, Japan, and China.

Bullet trains routinely travel at least 200 mph, whereas Acela trundles along at a pedestrian 84 mph, and there is no indication (and probably no intention) of that gap closing anytime soon.

U.S. passenger rail services in general are money-losing and antiquated versus their global counterparts, an inarguable (and to public transport proponents, embarrassing) fact. Passenger rail is just one part of the story, and serves as an excellent example of how not to manage a rail system. In fairness, efforts to turn Amtrak around (mainly through aggressive cost cutting) do seem to be having an impact, as current year losses total a shade under $30 million. It’s an admirable effort to be sure, but decades of losses, poor service, and general mismanagement cannot be ignored.

The U.S. freight railway system, conversely, is the envy of the world, and this is not hyperbole or chest thumping; the facts back it up. Since the Staggers Act of 1980, which deregulated freight rail, improvements have been substantial. U.S. freight railways carry 81% more ton-miles of freight, and costs have fallen 46%. (It isn’t common for an industry to increase its capacity by 81% while reducing costs by nearly half.) That level of success has even been noted by the Community of European Railway and Infrastructure Companies, which might be surprising, given the common assumption that Europe has a monopoly on rail excellence.

Compared side by side, it seems a conundrum: Amtrak limps along, still relying upon billions of dollars worth of taxpayer-financed subsidies, while U.S. freight railways evince growing profitability and capacity amid rapidly falling costs. Why are U.S. freight rails so profitable when U.S. passenger rail – sometimes traveling the same routes, on some of the same rails – remains a perennial money pit?

August 15, 2019

Amtrak is considering reviving at least one Chicago-Toronto passenger train

Lauren O’Neill reports on an Amtrak service extension proposal:

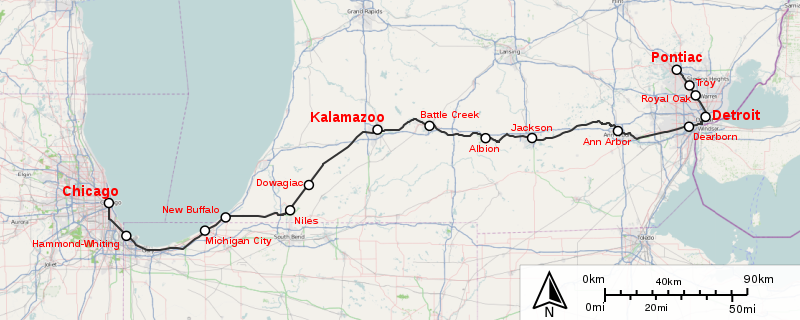

Amtrak P42DC locomotive #29 with a Blue Water or Wolverine train waits on a siding for a train in the opposite direction to pass in Comstock, Michigan.

The largest passenger railroad service in U.S. is considering a proposal that, if approved, would see trains running directly from Chicago to Toronto and back.

As discussed at the Michigan Rail Conference in East Lansing last week, Amtrak wants to extend its Wolverine line — which currently sees trains moving back and forth between Pontiac, MI, and Chicago, IL, three times per day — all the way up to Canada’s largest city.

A presentation slide shared by an official Michigan Department of Transportation Twitter account on Thursday shows that Amtrak wants to extend “at least one” Wolverine train into Ontario, “where it could continue as a VIA Rail Canada corridor service from Windsor/Walkerville to Toronto.”

It won’t happen overnight, and there’s plenty of work to be done in order for the train service to work, including the construction of a new border processing facility.

February 15, 2019

European-style passenger railways don’t scale to North American distances

At PJ Media, Charlie Martin does a good job of showing why the fast, efficient passenger railways of Europe are not replicated in the US and Canada:

… the usual story is something like “the United States should have a world-class passenger train system, with high-speed rail like the French and Japanese have.” @AOC’s official-no-fake-no-just-a-draft-Republican-conspiracy-theory-why-are-you-all-being-mean? Green New Deal FAQ wanted one so good that air travel would become “unnecessary.”

Sounds great, and I love the covert “MAGA” aspect of the pitch, but it has one great big, pretty much insurmountable problem: America.

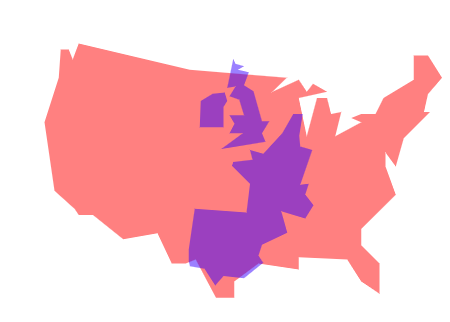

Not the country, the geography. People living on the coasts just don’t realize how big this country is. I was discussing it on Twitter with a Swiss who lives in Zürich who was telling me how great the Europeans trains are — and they really are comfortable, pretty fast, have great scenery to look at — but, well, let’s compare Colorado and Switzerland. Similar climate, mountains, pretty scenery, cranky natives who are suspicious of newcomers. But let’s go to the maps:

Colorado is 6.5 times as big, has 60 percent of the population — and, it happens, about two-thirds of the gross “national” product per capita.

Compare the lower 48 states with all of Western Europe:

The truth is, we’re in flyover country out here. The coastal clerisy don’t realize that on their five-hour flight from LAX to LGA they’re traveling 2,500 miles. Now, back in the days of the Super Chief and the 20th Century Limited, you could make that trip by train in only 76 hours, not counting changing trains in Chicago. (It takes longer on Amtrak.)

So, let’s say we could get high-speed trains for the whole trip that averaged 200 miles per hour, and could travel as the crow flies: that’s 12.5 hours.

Except of course you couldn’t because the crow is flying over some of the highest mountains in the country. You’re going to need rights of way, and you can’t use the rights of way that exist because they’re not suited for that kind of speed and they’re pretty full anyway. Also, it wouldn’t do to interrupt the existing freight lines, which actually are about as good as anywhere in the world.

November 28, 2018

The bitter economics of North American passenger railways

Earlier this month, I posted an excerpt from The Romance of the Rails, by Randal O’Toole. It’s a book I haven’t yet read, but based on what I’ve heard, his analysis of the state of US and Canadian passenger rail is both savage and accurate — as in, we’re insane to subsidize long-distance or high-speed rail for the wealthy out of the taxes levied on the poor. Recently, Trains columnist Fred Frailey got a chance to chat with O’Toole about his work:

That was one of the pleasures of reading your book, to discover you are a lover of trains and railroads, and that you marry this with a contrarian way of thinking. Do you take perverse pleasure in that combination? Oh, not at all. To me, it’s really sad. I wish I could support passenger trains, and I do support them as far as riding them and things like that. But I know enough about government subsidies to know that they reduce overall productivity and usually end up taking from the poor and giving to the rich. The people who are riding the Acela are not people in need of government handouts. The people who are riding light rail and things like that are not the poor, by and large.

What is the future of the long-distance trains? The role they fulfill is giving people access to scenery they can’t see in any other way, and really, it ends up being something for the wealthy. I think the Rocky Mountaineer model is the future of long-distance trains, and if you look at the United States, where can we have a Rocky Mountaineer? Certainly, Oakland to Denver, probably Oakland to Los Angeles, and after that, it gets pretty iffy. They would become cruise trains.

You seem almost as uncharitable towards the short-distance passenger trains. Amtrak does its best to deceive people about how well these trains do, for example, counting state subsidies as “passenger revenues,” in order to make itself eligible for more subsidies. I wouldn’t mind short-distance trains if they worked, but the Cascades, the California service, those trains aren’t really doing anything. A lot of money is spent carrying not that many people.

[…]

Statistics of yours that struck me are that public transit paid 90 percent of operating costs in 1964 from fares and just 32 percent today. Why not try to make the rail part of public transit more viable? You don’t address that in your book. You can’t make it more economically viable, simply because buses are so much better in every respect than rails. If you take the rail lines, and pave them over, and turn them into busways, you’ll be able to move more people, faster and cheaper and with far lower maintenance costs. Even if you could make the rails pay for themselves, since the buses are so much cheaper, why would we bother?

You seem most upset at places like Orlando and Dallas and Nashville, where commuter rail or light rail began but so few seem to ride. It this money thrown to the wind? I think so. Why is it that we allowed steam to change to diesel, sailing ships to steam ships — all these different technological evolutions to take place — but when it came to passenger rail, we said, “Halt, we don’t want more technological change.” The answer is threefold. It’s nostalgia. It’s people who are making money from wasting money, such as contactors — crony capitalism. And it’s accidents of history. The accident of history affecting urban rail transit was in 1973. Governor Francis Sargent of Massachusetts asked Congress to let cities substitute capital investments in transit for interstate highway grants. Congress said yes, but you can’t spend that amount of money on new busses. Instead, cities such as Buffalo, Portland, and San Jose built new rail lines with money from cancelled freeways because they are expensive and could use up those federal dollars. That’s what started the light-rail revolution, not because it was cheap, but because it was expensive.

November 15, 2018

The Romance of the Rails

Randal O’Toole’s new book on North American railways goes straight to my “wish list”. He’s also a long-time fan of railways, but has been forced to admit that attempts to bring back the golden age of rail are wasted effort because railways — especially US and Canadian lines — are built to carry bulk freight efficiently and economically but attempts to also carry large numbers of passengers quickly cannot be successful without building entirely separate (high-speed) lines. This is from the introduction to The Romance of the Rails [PDF]:

Amtrak’s

Eastbound Empire Builder crossing Two Medicine Trestle at East Glacier MT on 20 July 2011.

Photo by Steve Wilson via Wikimedia Commons.

Early in my career, I joined the National Association of Railroad Passengers (NARP) and supported more funding for Amtrak. Later, I realized Amtrak was poorly managed and supported Amtrak reform. More recently, along with NARP founder Anthony Haswell — who is sometimes called the Father of Amtrak — I became completely disillusioned with the idea of government-run trains and have argued for abolishing the heavily subsidized federal passenger rail corporation.

My attitudes toward urban transit have also undergone a transition. In 1972, as an undergraduate student, I wrote a paper for the Oregon Student Public Interest Research Group (OSPIRG) advocating low-cost transit improvements in Portland aimed at attracting people out of their automobiles and reducing air pollution. When the director of OSPIRG later became general manager of TriMet, Portland’s transit agency, he implemented some of those improvements, and transit ridership surged. To be honest, I didn’t propose rail transit reform in 1972 simply because I didn’t think there was much chance of that happening. However, I later became more skeptical of rail transit when Portland built an expensive light-rail line, followed by more lines that were even more expensive.

That skepticism has led some people to call me “anti-transit” and “anti-passenger train.” But I’m not. If someone could design a rail system that attracted riders and efficiently moved them from place to place, I’d be the first to endorse it. As this book will show, however, this is no more likely to happen than the freight railroads converting back to steam power. The next technology replacement will not be people trading in their cars for high-speed trains and light rail. Rather, it will be people trading in their human-driven cars for increasingly autonomous cars that drive themselves.

The short answer to the question of why passenger trains and streetcars have been replaced by planes, cars, and buses is that rails are more expensive and less flexible than the alternatives. To understand why, the first 10 chapters of this book will delve deep into the history of rail to show how passenger rail transportation once worked, who it worked for, and what has changed so that it no longer works today. This history demonstrates why statements such as, “High-speed trains have faster downtown-to-downtown times than flying” or “Light rail provides an alternative to congested roads going to work” are not relevant. Chapter 11 discusses the question of why passenger rail seems to work in Europe and Asia but not in North America.

Chapters 12 through 17 will each focus on a different kind of passenger rail, from streetcars to high-speed rail. Finally, Chapter 18 will demonstrate why we love trains, but also why we can’t expect them to do for us what they did in the 19th century.

Passenger rail was once an important part of our history, but today it represents a drag on our economy. I still love passenger trains, but I don’t think other people should have to subsidize my hobby.

September 2, 2018

Amtrak service and the “takings” clause

Back in August, Fred Frailey reluctantly came to the conclusion that at some point American freight railways are going to have to challenge in court Amtrak’s legislated ability to pre-empt freight traffic on their networks:

Amtrak’s

Eastbound Empire Builder crossing Two Medicine Trestle at East Glacier MT on 20 July 2011.

Photo by Steve Wilson via Wikimedia Commons.

We all know about “taking the Fifth.” It’s our right under the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution not to be compelled to testify against ourselves. In other words, a court cannot force us to admit to driving 60 mph in a 45-mph zone (or something worse). That amendment has another, less-well-known clause, which says government cannot take away our property without just compensation. Lawyers know this as the “Takings Clause.” The Fifth came to mind the other day as I rode Amtrak’s Empire Builder from Seattle to Chicago. I’ll get to my point, but first the experience.

[…]

All of this did terrible things to our schedule-keeping. By the third morning, as the train approached Devils Lake, N.D., we were more than eight hours late (the next day’s eastbound Builder was even later). But imagine what the Empire Builder does to BNSF’s freights every day. The Amtrak Improvement Act of 1973 reads: “Except in an emergency, intercity passenger trains operated by or on behalf of [Amtrak] shall be accorded preference over freight trains in the use of any given line of track, junction, or crossing.”

BNSF appears totally committed to obedience of this law but doing so devours the capacity of this route. It’s not just that freights give way; whizzing along at a 79 mph versus 55 or 60 for the freights, the Empire Builder eats capacity as if it were two or three freights, Six high-priority Z trains prowl the northern Transcon every day, and I don’t think a single one of them that I observed was moving as we went by. One Z train was sandwiched between two stopped manifest trains, all making way for our Builder.

Obviously, Amtrak pays BNSF for the right to run trains over the freight railroad. But whatever it pays is but a fraction of the cost in delays to its own trains incurred by BNSF. Were the northern Transcon double-tracked all the way, these delays would obviously be minimized. But at $3 million or more a mile, double tracking consumes capital like a dry sponge, and it’s not Amtrak’s capital, either.

So now to my point: Isn’t it fair to say that Amtrak, which the U.S. Supreme Court in 2015 decreed to be an arm of government, is confiscating the property (track capacity) of host railroads? And if it is, shouldn’t the freight railroads be fairly compensated for the delays to their freights caused by the loss of this capacity? Try as I might to say otherwise, I am forced to answer “yes” to both questions.

April 5, 2018

Amtrak decides to abandon one of its few profitable sidelines

Kevin Keefe discusses the recent Amtrak announcement that it will be discontinuing support for private railcar movements on Amtrak trains:

Amtrak’s announcement last week that it intends to shut down most of its haulage of private cars and its support for special trains was a stunner. Within hours, hundreds or perhaps thousands of people working in the heritage end of railroading scrambled to react.

It hasn’t taken long for a credible protest movement to take root. An official objection was made to Amtrak on behalf of the American Association of Private Car Owners, and a similar move is expected from the Rail Passenger Car Alliance. Railfan social media has erupted with protest exhortations. As of this morning, more than 7,000 people have signed a petition at change.org.

Meanwhile, in this moment of limbo, a number of plans have been put on hold. The Fort Wayne Railroad Historical Society has postponed ticket sales for its September 15-16 “Joliet Rocket” trips on Chicago’s Metra, featuring Nickel Plate 2-8-4 No. 765. The operators of West Virginia’s famed New River Train fall foliage trips — a 51-year tradition — are faced with closing up shop. Like all private-car owners, the Washington, D.C., Chapter, NRHS, might wonder when its heavyweight Pullman Dover Harbor might once again turn a wheel. Countless other organizations face the same dilemma.

In announcing the new policy, Amtrak President and CEO Richard Anderson cited three main reasons why the company feels this move is necessary: operational distractions from providing for special moves, a failure to capture “fully allocated profit margins,” and delays to paying customers on scheduled trains.

One thing Anderson didn’t mention in his announcement, but should have: the subsidy the American taxpayer gives to prop up his corporation every year. In 2017, that largesse amounted to $1.495 billion.

Anderson’s complaints about the effects of special moves are specious. Amtrak has plenty of “operational distractions,” but most of them have little to do with factors related to private cars or special trains, the grateful operators of which strive mightily to make their moves seamless. As for delays, why isn’t Anderson pointing the finger at the real culprits, some of their Class I partners for whom delaying a passenger train is second nature? As for relative profitability, if it’s true that the “special trains” business operates in the black, how can Amtrak walk away from it? Where else does Amtrak make a profit?

July 2, 2015

Frankford Junction, Pennsylvania

Rob McGonigal looks at the history of the railways in the area of Frankford Junction, where Amtrak train 188 came to grief in May:

In the aftermath of the tragic May 12 derailment due to excessive speed of Amtrak train 188 in Philadelphia, many casual observers wondered what a 50-mph curve is doing in the middle of the fastest, busiest rail corridor in the nation. It’s a reasonable question, especially given the generally tangent track and flat topography in the area.

The existence of that curve traces back to the earliest years of railroads in Philadelphia. As in many cities, Philadelphia’s rail network developed in piecemeal, uncoordinated fashion. What became Amtrak 188’s route through the city began in the 1830s as three separate projects.

The Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore ran generally southwestward from a terminal about a mile south of downtown (“center city” to Philadelphians). The Philadelphia & Columbia, part of the Main Line of Public Works rail/canal system to Pittsburgh, utilized a terminal in center city. The Philadelphia & Trenton, which connected with services to New York, originated in Kensington — an inconvenient 2½ miles northeast of center city. As Albert Churella relates in the first volume of his mammoth history of the PRR (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), municipal authorities in 1840 granted the P&T permission to extend its line into center city, where it would connect with other railroads. However, fierce opposition from teamsters, who profited from hauling freight between the rail terminals, and area residents, who did not want steam trains in their streets, prompted the city to revoke permission, and the P&T was not extended.

Two decades later, it was clear that the three lines should be connected. In 1864 the Junction Railroad was opened, linking the PW&B with the P&C’s successor on the line to the west — the Pennsylvania Railroad. (Indeed, the PRR had interests in all three of the lines by this time.) Three years later the Connecting Railway opened. It diverged from the P&C/PRR line at a place designated Mantua Junction (and later, in expanded form, Zoo interlocking), arced around the northern part of the city, and connected with the P&T in the Frankford section of Philadelphia. As with the connection at Mantua Junction, the geometry of the lines at Frankford Junction resulted in a sharp curve.