This month’s fallen flag article for Classic Trains is the story of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway by George Drury:

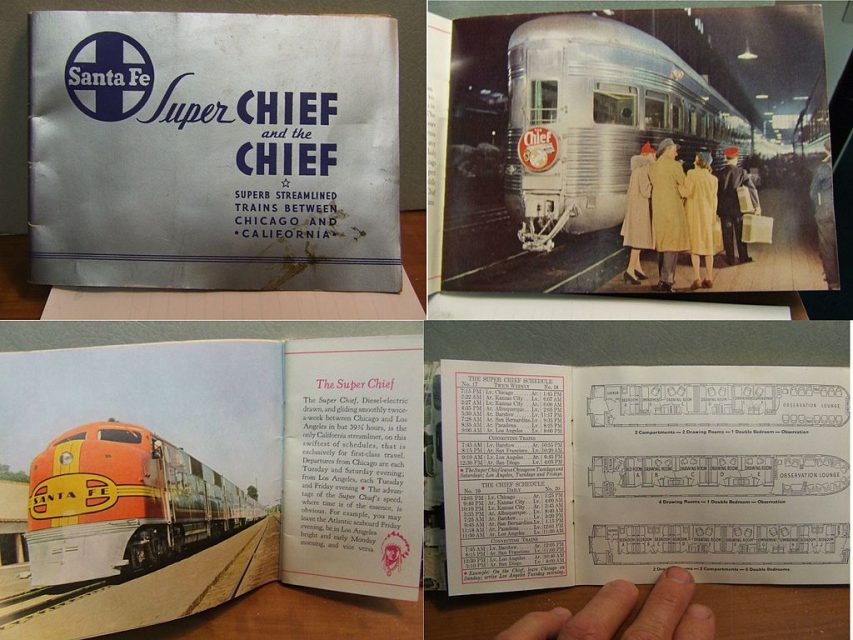

Pages from a circa 1937 booklet about the Santa Fe trains The Chief and the Super Chief. The railroad was showcasing the streamlined changes made to its main Chicago to California trains. Super Chief had given up its boxcab locomotives for EMC E1 units. Chief was no longer pulled by the “Blue Goose” steam locomotive, but by EMD diesel locomotives.

Wikimedia Commons.

The Atchison & Topeka Railroad was chartered in 1859 to join the towns of its title and continue southwest toward Santa Fe, New Mexico.

“Santa Fe” was added to the corporate name in 1863. Construction started in 1869; by the end of 1872 the railroad extended to the Kansas-Colorado border, opening much of Kansas to settlement and carrying wheat and cattle east to markets. The railroad temporarily set aside its goal of Santa Fe — once the trading capital of the Spanish colony in that area — and continued building west, reaching Pueblo, Colorado, in 1876, just in time for the silver rush at Leadville, Colorado.

In 1878, the railroad resumed construction toward Santa Fe, building southwest from La Junta to Trinidad, Colorado, then south over Raton Pass. It chose that route instead of an easier route south across the plains from Dodge City because of Native American attacks and a lack of water on the southerly route and coal deposits near Trinidad, Colorado, and Raton, New Mexico.

The Denver & Rio Grande was also aiming at Raton Pass, but Santa Fe crews arose early one morning in 1878 and were hard at work with picks and shovels when the Rio Grande crews showed up after breakfast. At the same time the two railroads skirmished over occupancy of the Royal Gorge of the Arkansas River west of Canon City, Colorado; the Rio Grande won that battle.

The Santa Fe reached Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1880 (because of geography the city of Santa Fe found itself at the end of a short branch from Lamy, New Mexico) and connected with the Southern Pacific at Deming, New Mexico, in 1881. The Santa Fe then built southwest from Benson, Arizona, to Nogales, on the Mexican border. There it connected with the Sonora Railway, which Santa Fe interests had constructed north from the Mexican port of Guaymas.

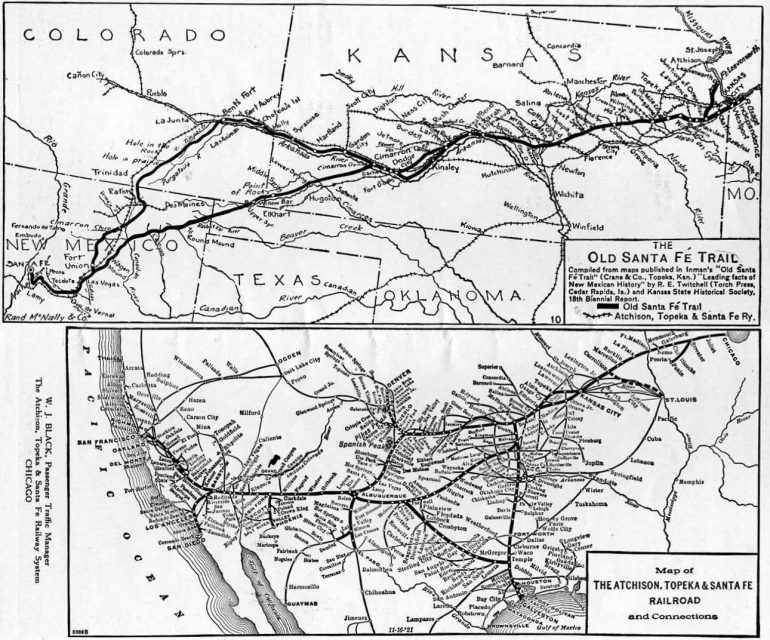

Comparison map showing the Santa Fe Trail and the ATSF Railway, 1922.

Map from By the Way – A condensed guide of points of interest along the Santa Fe lines to California, Rand McNally and Company via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1960 the Santa Fe bought the Toledo, Peoria & Western Railroad, then sold a half interest to the Pennsylvania Railroad. The TP&W cut straight east across Illinois from near Fort Madison, Iowa, to a connection with the Pennsy at Effner, Indiana, forming a bypass around Chicago for traffic moving between the two lines. The TP&W route didn’t mesh with the traffic pattern Conrail developed after 1976, so Santa Fe bought back the other half, merged the TP&W in 1983, then sold it back into independence in 1989.

During the 1960s the Santa Fe explored merger with the Frisco and the Missouri Pacific with no success. By 1980 Santa Fe, which had been the top railroad in route mileage in the 1950s, was surrounded by larger railroads. It was well managed and profitable, and it had the best route between the Midwest and Southern California, but its neighbors were larger, and friendly connections had been taken over by rival railroads. Southern Pacific was in the same situation. In 1980 Santa Fe and SP proposed merger. Approval seemed certain, but in 1986 the Interstate Commerce Commission denied permission because the merger would create a railroad monopoly in New Mexico, Arizona, and California.

The Santa Fe, suddenly the smallest of the Super Seven freight railroads, began spinning off branches and secondary lines and became primarily a conduit for containers and trailers moving between the Midwest and Southern California. In June 1994 Santa Fe and Burlington Northern announced their intention to merge — BN would buy Santa Fe. The deal was consummated in 1995, forming the Burlington Northern Santa Fe, known today as BNSF Railway.

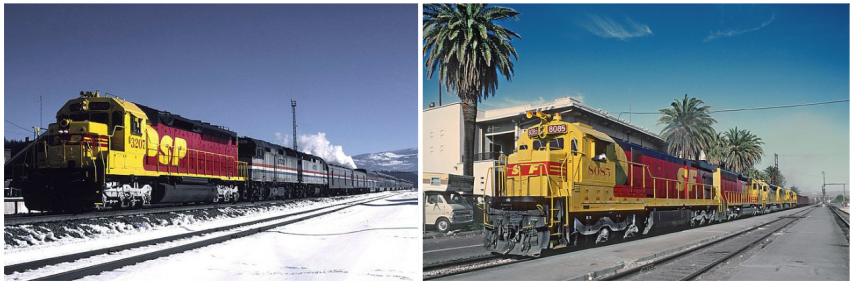

The denied merger between the Southern Pacific and the Santa Fe included an eye-catching proposed “Kodachrome” paint scheme for locomotives, as described in the Wikipedia article:

The holding company controlled all the rail and non-rail assets of the former Santa Fe Industries and Southern Pacific Company, and it was intended that the two railroads would be merged. They were confident enough that this would be approved that they began repainting locomotives into a new unified paint scheme, including the letters SP or SF and an adjacent empty space for the other two (as SPSF, the reverse order of the holding company).

The locomotive livery featured the Santa Fe’s Yellowbonnet with a red stripe on the locomotive’s nose; the remainder of the locomotive body was painted in Southern Pacific’s scarlet red (from their Bloody Nose scheme) with a black roof and black extending down to the lower part of the locomotive’s radiator grills. The numberboards were red with white numbers. In large block letters within the red portion of the sides was either “SP” (for Southern Pacific-owned locomotives) or “SF” (for Santa Fe-owned locomotives). The lettering was positioned on the locomotive sides so that the other half of the lettering could be added after the merger became official. Two ATSF EMD SD45-2s (ATSF #7219 and #7221) were painted with the full SPSF lettering to show what the unified paint scheme would look like after the merger was complete. One Santa Fe caboose was also painted with “SPSF” in a similar situation.

This paint scheme, combining yellow, red and black, has come to be called the Kodachrome paint scheme due to the colors’ resemblance to those on the boxes that Kodak used to package its Kodachrome slide film (which was heavily used by railfans of the time). After the ICC’s denial, railroad industry writers, employees of both railroads and railfans alike joked that SPSF really stood for “Shouldn’t Paint So Fast”.