Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 6 Jun 2023

(more…)

June 10, 2023

Feeding a Greek Hoplite – Ancient Rations

June 8, 2023

QotD: Heroes, demi-gods and gods in the ancient Greek world

A handful of heroes from Greek mythology become gods as part of their story. The most famous of these is Heracles, raised to godhood at his death, along with Castor and Pollux – twin demi-god heroes with enough divinity between them to make one of them god and they alternated the honor. Leucothea (lit: the white goddess) – the divine form of the woman Ino – makes her appearance in the Odyssey (Book 5!) to save Odysseus.

These figures – complete with tales of being swept up into divinity while still alive or at the moment of their death – are in some way atypical of hero worship in the Greek world. More typical is a figure like Achilles, who very definitely was mortal and very definitely died and whose spirit is very much in the Underworld in the Odyssey (and neatly contrasted with Heracles – only Heracles’ shade is in the underworld, for his soul was divine; but cf. Pindar on Achilles, Olympia 2.75-85). Our sources (e.g. Plin. Nat. 4.26) continue to speak of Achilles as a man, with a physical tomb. And yet Alexander pays him honors (Arr. Anab. 1.12.1) and we have ample evidence for cult observances of Achilles in the Greek world. it was possible to be a man in life, and yet have enough influence to be worthy of cult in death.

This sounds strange, but its worth noting that some of the most common mortal figures to receive this kind of cult worship were founder figures – people (often legendary or mythical in nature) credited with the foundation of a community. We’ve actually discussed that here before in Lycurgus and Theseus, but as you might imagine, such figures were very common. It is not entirely crazy to assume that these figures have some power to shape your world or life, because they already have – you live in the city they founded! They deeds in life continue to shape the confines of your experience – why wouldn’t that influence, in some way, carry with them?

(And while I’m here, I should note that the American architectural veneration of our founder figures on the National Mall is explicitly framed in terms of Mediterranean cult observance. The Lincoln and Jefferson memorials both borrow their forms from Roman temples and contain super-life-sized cult statues exactly as and where a Roman temple would has the cult statue of the god, while the Washington Monument – as an Egyptian style obelisk – mimics Egyptian practice quite intentionally. We even have our monuments to the di manes [the divine shades of your dead ancestors who watch over you] in our war memorials, framed around collective veneration. A Roman time-traveler would have no problem interpreting the display, and might think the many millions of visitors coming from all corners quite pious in their observance.)

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Practical Polytheism, Part IV: Little Gods and Big People”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-11-15.

May 25, 2023

The Hoplite Heresy: Why We Don’t Know How the Ancient Greeks Waged War

The Historian’s Craft

Published 9 Feb 2023Hoplites are probably one of the first things that come to mind when one thinks of “Ancient Greece”. Equipped with a bronze spear and wearing bronze armor or a linothorax, and hefting the aspis — the hoplite‘s bronze shield — they fought in phalanxes. The classic mode of fighting in this formation was the “othismos“, the push, with the aim being to disrupt the enemy phalanx and break their formation. But, over the past few decades, views on hoplite warfare have been called into question and seriously revised, because there are problems in the source material. So, what are these problems, and how do historians of Ancient Greece understand hoplite warfare?

May 23, 2023

Mustard: A Spicy History

The History Guy: History Deserves to be Remembered

Published 15 Feb 2023In 2018 The Atlantic observed “For some Americans, a trip to the ballpark isn’t complete without the bright-yellow squiggle of French’s mustard atop a hot dog … Yet few realize that this condiment has been equally essential — maybe more so — for the past 6,000 years.”

(more…)

May 15, 2023

QotD: How military history shapes cultures and societies

… war and conflict deeply shaped societies in the past and to the degree that we think that understanding those societies is important (a point on which, presumably, all historians may agree), it is also important to understand their conflicts. I am often puzzled by scholars who work on bodies of literature written almost entirely by combat veterans (which is a good chunk of the Greek and Latin source tradition), in societies where most free adult men probably had some experience of combat, who then studiously avoid ever studying or learning very much about that combat experience (that “war and society” lens there again). Famously, Aeschylus, the greatest Greek playwright of his generation, left no record of his achievements in writing in his epitaph. Instead he was commemorated this way:

Aeschylus, son of Euphorion, the Athenian lies beneath this marker

having perished in wheat-bearing Gela

Of his well-known prowess, the grove of Marathon can speak

And long-haired Mede knows it well.If a scholar wants to understand Aeschylus or his plays, don’t they also need to understand this side of his experience too? I know quite a number of scholars who ended up coming to military history this way, looking to answer questions that were not narrowly military, but which ended up touching on war and conflict. For that kind of research – for our potential scholar of Aeschylus – it is important that there be specialists working to understand war and conflict in the period. Of course this is particularly true in understanding historical politics and political narratives, given that most pre-modern states were primarily engines for the raising of revenues for the waging of war (with religious expenditures typically being the only ones comparable in scale).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Why Military History?”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-11-13.

May 11, 2023

QotD: Divination

Divination is often casually defined in English as “seeing into the future”, but the root of the word gives a sense of its true meaning: divinare shares the same root as the word “divine” (divinus, meaning “something of, pertaining or belonging to a god”); divination is more rightly the act of channeling the divine. If that gives a glimpse of the future, it is because the gods are thought to see that future more clearly.

But that distinction is crucial, because what you are actually doing in a ritual involving divination is not asking questions about the future, but asking questions of the gods. Divination is not an exercise in seeing, but in hearing – that is, it is a communication, a conversation, with the divine. […]

Many current religions – especially monotheistic ones – tend to view God or the gods as a fundamentally distant, even alien being, decidedly outside of creation. The common metaphor is one where God is like a painter or an architect who creates a painting or a building, but cannot be in or part of that creation; the painter can paint himself, but cannot himself be in the painting and the architect may walk in the building but she cannot be a wall. Indeed, one of the mysteries – in the theological sense […] – of the Christian faith is how exactly a transcendent God made Himself part of creation, because this ought otherwise be inconceivable.

Polytheistic gods do not work this way. They exist within the world, and are typically created with it (as an aside: this is one point where, to get a sense of the religion, one must break with the philosophers; Plato waxes philosophic about his eternal demiurge, an ultimate creator-god, but no one in Greece actually practiced any kind of religion to the demiurge. Fundamentally, the demiurge, like so much fine Greek writing about the gods, was a philosophical construct rather than a religious reality). As we’ll get to next week, this makes the line between humans and gods a lot more fuzzy in really interesting ways. But for now, I want to focus on this basic idea: that the gods exist within creation and consequently can exist within communities of humans.

(Terminology sidenote: we’ve actually approached this distinction before, when we talked about polytheistic gods being immanent, meaning that they were active in shaping creation in a direct, observable way. In contrast, monotheistic God is often portrayed as transcendent, meaning that He sits fundamentally outside of creation, even if He still shapes it. Now, I don’t want to drive down the rabbit hole of the theological implications of these terms for modern faith (though I should note that while transcendence and immanence are typically presented as being opposed qualities, some gods are both transcendent and immanent; the resolution of an apparent contradiction of this sort in a divine act or being like this is what we call a mystery in the religious sense – “this should be impossible, but it becomes possible because of divine action”). But I do want to note the broad contrast between gods that exist within creation and the more common modern conception of a God whose existence supersedes the universe we know.)

Thus, to the polytheistic practitioner, the gods don’t exist outside of creation, or even outside of the community, but as very powerful – and sometimes inscrutable – members of the community. The exact nature of that membership varies culture to culture (for instance, the Roman view of the gods tends towards temperamental but generally benevolent guardians and partners of the state, whereas the Mesopotamian gods seem to have been more the harsh rulers set above human society; that distinction is reflected in the religious structure: in Rome, the final deciding body on religious matters was the Senate, whereas Mesopotamian cities had established, professional priesthoods). But gods do a lot of the things other powerful members of the community do: they own land (and even enslaved persons) within the community, they have homes in the community (this is how temples are typically imagined, as literal homes-away-from-home for the gods, when they’re not chilling in their normal digs), they may take part in civic or political life in their own unique way. […] some of these gods are even more tightly bound to a specific place within the community – a river, stream, hill, field.

And, like any other full member of the community (however “full membership” is defined by a society), the gods expect to be consulted about important decisions.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Practical Polytheism, Part III: Polling the Gods”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-11-08.

May 4, 2023

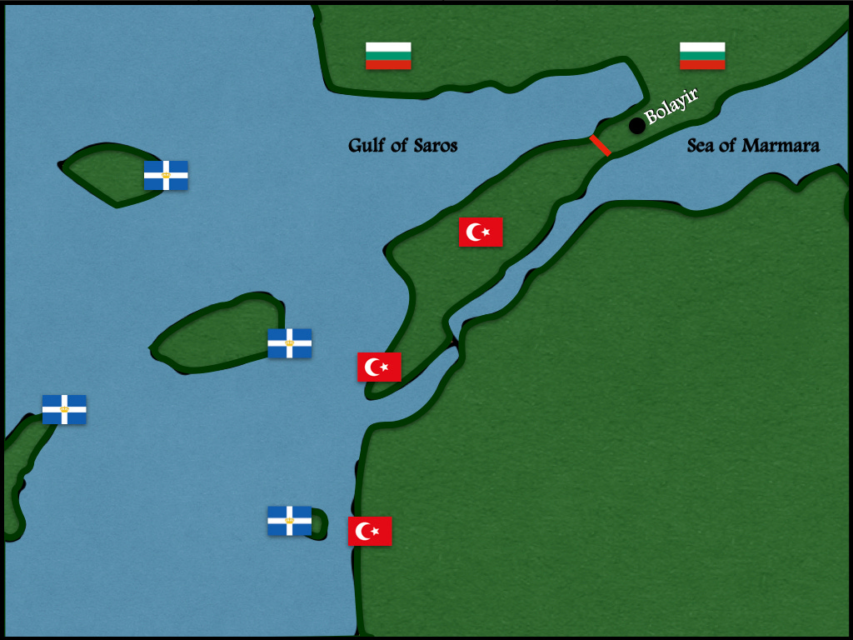

Fierce fighting on Gallipoli … before WW1

Bruce Gudmundsson outlines the operations of Ottoman Empire forces defending “Turkey in Europe” against Greek and Bulgarian invasion (in alliance with Serbia and Montenegro) in 1913:

In the English speaking world, the name Gallipoli invariably evokes memories of the great events of 1915 and 1916. A location of such strategic importance, however, rarely serves as the site of a single battles. Two years before the landings of the British, Indian, Australian, and New Zealand troops on the south-west portion of the the peninsula (and the concurrent French landings on the nearby mainland of Asia Minor near the ruins of the ancient city of Troy), Ottoman soldiers defended the Dardanelles against the forces of the Balkan League.

By the end of January of 1913, the combined efforts of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria had driven Ottoman forces from most of “Turkey in Europe”. Indeed, the only intact Ottoman formations on European soil were those trapped in the fortress of Adrianople, those holding the fortified line just west of Constantinople, and those that had recently arrived at Gallipoli.

Soon after arriving, the Ottoman forces on Gallipoli began to build a belt of field fortifications across the narrowest part of the peninsula, a line some five kilometers (three miles) west of the the town of Bolayir. At the same time, they occupied outposts some twenty kilometers east of the line, at the place where the peninsula connected to the mainland.

On 4 February 1913, the Bulgarians attacked. On the first day of this attack, they drove in the Ottoman outposts. On the second day, they broke through a hastily erected line of resistance, thereby convincing the Ottoman forces in front of them to evacuate Bolayir. However, rather than taking the town, or otherwise attempting to exploit their victory, they withdrew to positions some ten kilometers (six miles) east of the Ottoman earthworks.

While the Ottoman land forces returned to the earthworks along the neck of the Peninsula, ships of the Ottoman Navy operating in the Sea of Marmora located, and began to bombard, the Bulgarian forces near the coast. This caused the Bulgarians to move inland, where they took up, and improved, new positions on the rear slopes of nearby hills.

On 9 February, the Ottomans launched a double attack. While the main body of the Ottoman garrison of Gallipoli advanced overland, a smaller force, supported by the fire of Ottoman warships, landed on the far side of the Bulgarian position. Notwithstanding the advantages, both numerical and geometric, enjoyed by the Ottoman attackers, this pincer action failed to destroy the Bulgarian force. Indeed, in the course of two failed attacks, the Ottomans suffered some ten thousand casualties.

Though the Ottoman maneuver failed to dislodge the Bulgarians from their trenches, the two-sided attack convinced the Bulgarian commander to seek ground that was, at once, both easier to defend against terrestrial attack and less vulnerable to naval gunfire. He found this on the east bank of a river, thirteen kilometers (eight miles) northeast of Bolayir and ten kilometers (six miles) north of the place where the Ottoman landing had taken place.

April 21, 2023

QotD: In ancient Greek armies, soldiers were classified by the shields they carried

Plutarch reports this Spartan saying (trans. Bernadotte Perrin):

When someone asked why they visited disgrace upon those among them who lost their shields, but did not do the same thing to those who lost their helmets or their breastplates, he said, “Because these they put on for their own sake, but the shield for the common good of the whole line.” (Plut. Mor. 220A)

This relates to how hoplites generally – not merely Spartans – fought in the phalanx. Plutarch, writing at a distance (long after hoplite warfare had stopped being a regular reality of Greek life), seems unaware that he is representing as distinctly Spartan something that was common to most Greek poleis (indeed, harsh punishments for tossing aside a shield in battle seemed to have existed in every Greek polis).

When pulled into a tight formation, each hoplite‘s shield overlapped, protecting not only his own body, but also blocking off the potentially vulnerable right-hand side of the man to his left. A hoplite‘s armor protected only himself. That’s not to say it wasn’t important! Hoplites wore quite heavy armor for the time-period; the typical late-fifth/fourth century kit included a bronze helmet and the linothorax, a laminated, layered textile defense that was relatively inexpensive, but fairly heavy and quite robust. Wealthier hoplites might enhance this defense by substituting a bronze breastplate for the linothorax, or by adding bronze greaves (essentially a shin-and-lower-leg-guard); ankle and arm protections were rarer, but not unknown.

But the shield – without the shield one could not be a hoplite. The Greeks generally classified soldiers by the shield they carried, in fact. Light troops were called peltasts because they carried the pelta – a smaller, circular shield with a cutout that was much lighter and cheaper. Later medium-infantry were thureophoroi because they carried the thureos, a shield design copied from the Gauls. But the highest-status infantrymen were the hoplites, called such because the singular hoplon (ὅπλον) could be used to mean the aspis (while the plural hopla (ὁπλά) meant all of the hoplite‘s equipment, a complete set).

(Sidenote: this doesn’t stop in the Hellenistic period. In addition to the thureophoroi, who are a Hellenistic troop-type, we also have Macedonian soldiers classified as chalkaspides (“bronze-shields” – they seem to be the standard sarissa pike-infantry) or argyraspides (“silver-shields”, an elite guard derived from Alexander’s hypaspides, which again note – means “aspis-bearers”!), chrysaspides (“gold-shields”, a little-known elite unit in the Seleucid army c. 166) and the poorly understood leukaspides (“white-shields”) of the Antigonid army. All of the –aspides seem to have carried the Macedonian-style aspis with the extra satchel-style neck-strap, the ochane)

(Second aside: it is also possible to overstate the degree to which the aspis was tied to the hoplite‘s formation. I remain convinced, given the shape and weight of the shield, that it was designed for the phalanx, but like many pieces of military equipment, the aspis was versatile. It was far from an ideal shield for solo combat, but it would serve fairly well, and we know it was used that way some of the time.)

Bret Devereaux, “New Acquisitions: Hoplite-Style Disease Control”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-03-17.

April 19, 2023

Philip II of Macedon (359 to 336 B.C.E.)

Historia Civilis

Published 24 May 2017

(more…)

April 6, 2023

QotD: The general’s pre-battle speech to the army

The modern pre-battle general’s speech is quite old. We can actually be very specific: it originates in a specific work: Thucydides’ Histories [of the Peloponnesian War] (written c. 400 B.C.). Prior to this, looking at Homer or Herodotus, commanders give very brief remarks to their troops before a fight, but the fully developed form of the speech, often presented in pairs (one for each army) contrasting the two sides, is all Thucydides. It’s fairly clear that a few of Thucydides’ speeches seem to have gone on to define the standard form and ancient authors after Thucydides functionally mix and match their components (we’ll talk about them in a moment). This is not a particularly creative genre.

Now, there is tremendous debate as to if these speeches were ever delivered and if so, how they were delivered (see the bibliography note below; none of this is really original to me). For my part, while I think we need to be alive to the fact that what we see in our textual sources are dressed up literary compressions of the tradition of the pre-battle speech, I suspect that, particularly by the Roman period, yes, such speeches were a part of the standard practice of generalship. Onasander, writing about the duties of a general in the first century CE, tells us as much, writing, “For if a general is drawing up his men before battle, the encouragement of his words makes them despise the danger and covet the honour; and a trumpet-call resounding in the ears does not so effectively awaken the soul to the conflict of battle as a speech that urges to strenuous valour rouses the martial spirit to confront danger.” Onasander is a philosopher, not a military man, but his work became a standard handbook for military leaders in Antiquity; one assumes he is not entirely baseless.

And of course, we have the body of literature that records these speeches. They must be, in many cases, invented or polished versions; in many cases the author would have no way of knowing the real worlds actually said. And many of them are quite obviously too long and complex for the situations into which they are placed. And yet I think they probably do represent some of what was often said; in many cases there are good indications that they may reflect the general sentiments expressed at a given point. Crucially, pre-battle speeches, alone among the standard kinds of rhetoric, refuse to follow the standard formulas of Greek and Roman rhetoric. There is generally no exordium (meaning introduction; except if there is an apology for the lack of one, in the form of, “I have no need to tell you …”) or narratio (the narrated account), no clear divisio (the division of the argument, an outline in speech form) and so on. Greek and Roman oratory was, by the first century or so, quite well developed and relatively formulaic, even rigid, in structure. The temptation to adapt these speeches, when committing them to a written history, to the forms of every other kind of oratory must have been intense, and yet they remain clearly distinct. It is certainly not because the genre of the battle speech was more interesting in a literary sense than other forms of rhetoric, because oh my it wasn’t. The most logical explanation to me has always been that they continue to remain distinct because however artificial the versions of battle speeches we get in literature are, they are tethered to the “real thing” in fundamental ways.

Finally, the mere existence of the genre. As I’ve noted elsewhere, we want to keep in mind that Greek and Roman literature were produced in extremely militarized societies, especially during the Roman Republic. And unlike many modern societies, where military service is more common among poorer citizens, in these societies military service was the pride of the elite, meaning that the literate were more likely both to know what a battle actually looked like and to have their expectations shaped by war literature than the commons. And that second point is forceful; even if battle speeches were not standard before Thucydides, it is hard to see how generals in the centuries after him could resist giving them once they became a standard trope of “what good generals do.”

So did generals give speeches? Yes, probably. Among other reasons we can be sure is that our sources criticize generals who fail to give speeches. Did they give these speeches? No, probably not; Plutarch says as much (Mor. 803b) though I will caution that Plutarch is not always the best when it comes to the reality of the battlefield (unlike many other ancient authors, Plutarch was a life-long civilian in a decidedly demilitarized province – Achaea – who also often wrote at great chronological distance from his subjects; his sense of military matters is generally weak compared to Thucydides, Polybius or Caesar, for instance). Probably the actual speeches were a bit more roughly cut and more compartmentalized; a set of quick remarks that might be delivered to one unit after another as the general rode along the line before a battle (e.g. Thuc. 4.96.1). There are also all sorts of technical considerations: how do you give a speech to so many people, and so on (and before you all rush to the comments to give me an explanation of how you think it was done, please read the works cited below, I promise you someone has thought of it, noted every time it is mentioned or implied in the sources and tested its feasibility already; exhaustive does not begin to describe the scholarship on oratory and crowd size), which we’ll never have perfect answers for. But they did give them and they did seem to think they were important.

Why does that matter for us? Because those very same classical texts formed the foundation for officer training and culture in much of Europe until relatively recently. Learning to read Greek and Latin by marinating in these specific texts was a standard part of schooling and intellectual development for elite men in early modern and modern Europe (and the United States) through the Second World War. Napoleon famously advised his officers to study Caesar, Hannibal and Alexander the Great (along with Frederick II and the best general you’ve never heard of, Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden). Reading the classical accounts of these battles (or, in some cases, modern adaptations of them) was a standard part of elite schooling as well as officer training. Any student that did so was bound to run into these speeches, their formulas quite different from other forms of rhetoric but no less rigid (borrowing from a handful of exemplars in Thucydides) and imbibe the view of generalship they contained. Consequently, later European commanders tended for quite some time to replicate these tropes.

(Bibliography notes: There is a ton written on ancient battle speeches, nearly all of it in journal articles that are difficult to acquire for the general public, and much of it not in English. I think the best possible place to begin (in English) is J.E. Lendon, “Battle Description in the Ancient Historians Part II: Speeches, Results and Sea Battles” Greece & Rome 64.1 (2017). The other standard article on the topic is E. Anson “The General’s Pre-Battle Exohortation in Graeco-Roman Warfare” Greece & Rome 57.2 (2010). In terms of structure, note J.C. Iglesias Zoida, “The Battle Exhortation in Ancient Rhetoric” Rhetorica 25 (2007). For those with wider language skills, those articles can point you to the non-English scholarship. They can also serve as compendia of nearly all of the ancient battle speeches; there is little substitute for simply reading a bunch of them on your own.)

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Battle of Helm’s Deep, Part VII: Hanging by a Thread”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-06-12.

April 4, 2023

History Summarized: the Ancient Greek Post-Apocalypse

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 31 Mar 2023Turns out the “Studio Ghibli Post-Apocalypse” aesthetic has a historical basis in ancient Greek history’s Bronze Age Collapse, long Dark Age, and slow re-emergence into the Polis Age. I don’t know if I’d call the process pleasant, but it sure as hell is a vibe.

GO READ THE ILIAD: https://bookshop.org/p/books/the-ilia… — We enjoy the Fagles translation, as it’s the typical classroom and library standard, but if you want a real treat, try the Alexander Pope edition from the 1700s that’s written entirely in RHYME. THE DAMN THING RHYMES!!!

SOURCES & Further Reading:

“The Age of Heroes” and “Delphi and Olympia” from Ancient Greek Civilization by Jeremy McInerney – “Dark Age and Archaic Greece” from The Foundations of Western Civilization by Thomas F. X. Noble – “Dark Age and Archaic Greece” from The Greek World: A Study of History and Culture by Robert Garland “The Greeks: A Global History” by Roderick Beaton, “The Greeks: An Illustrated History” by Diane Cline, Metropolitan Museum “Geometric Art in Ancient Greece” https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grg… also have a degree in Classical Studies

(more…)

March 29, 2023

QotD: Sacrifice

As a terminology note: we typically call a living thing killed and given to the gods a sacrificial victim, while objects are votive offerings. All of these terms have useful Latin roots: the word “victim” – which now means anyone who suffers something – originally meant only the animal used in a sacrifice as the Latin victima; the assistant in a sacrifice who handled the animal was the victimarius. Sacrifice comes from the Latin sacrificium, with the literal meaning of “the thing made sacred”, since the sacrificed thing becomes sacer (sacred) as it now belongs to a god, a concept we’ll link back to later. A votivus in Latin is an object promised as part of a vow, often deposited in a temple or sanctuary; such an item, once handed over, belonged to the god and was also sacer.

There is some concern for the place and directionality of the gods in question. Sacrifices for gods that live above are often burnt so that the smoke wafts up to where the gods are (you see this in Greek and Roman practice, as well in Mesopotamian religion, e.g. in Atrahasis, where the gods “gather like flies” about a sacrifice; it seems worth noting that in Temple Judaism, YHWH (generally thought to dwell “up”) gets burnt offerings too), while sacrifices to gods in the earth (often gods of death) often go down, through things like libations (a sacrifice of liquid poured out).

There is also concern for the right animals and the time of day. Most gods receive ritual during the day, but there are variations – Roman underworld and childbirth deities (oddly connected) seem to have received sacrifices by night. Different animals might be offered, in accordance with what the god preferred, the scale of the request, and the scale of the god. Big gods, like Jupiter, tend to demand prestige, high value animals (Jupiter’s normal sacrifice in Rome was a white ox). The color of the animal would also matter – in Roman practice, while the gods above typically received white colored victims, the gods below (the di inferi but also the di Manes) darkly colored animals. That knowledge we talked about was important in knowing what to sacrifice and how.

Now, why do the gods want these things? That differs, religion to religion. In some polytheistic systems, it is made clear that the gods require sacrifice and might be diminished, or even perish, without it. That seems to have been true of Aztec religion, particularly sacrifices to Quetzalcoatl; it is also suggested for Mesopotamian religion in the Atrahasis where the gods become hungry and diminished when they wipe out most of humans and thus most of the sacrifices taking place. Unlike Mesopotamian gods, who can be killed, Greek and Roman gods are truly immortal – no more capable of dying than I am able to spontaneously become a potted plant – but the implication instead is that they enjoy sacrifices, possibly the taste or even simply the honor it brings them (e.g. Homeric Hymn to Demeter 310-315).

We’ll come back to this idea later, but I want to note it here: the thing being sacrificed becomes sacred. That means it doesn’t belong to people anymore, but to the god themselves. That can impose special rules for handling, depositing and storing, since the item in question doesn’t belong to you anymore – you have to be extra-special-careful with things that belong to a god. But I do want to note the basic idea here: gods can own property, including things and even land – the temple belongs not to the city but to the god, for instance. Interestingly, living things, including people can also belong to a god, but that is a topic for a later post. We’re still working on the basics here.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Practical Polytheism, Part II: Practice”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-11-01.

March 25, 2023

QotD: Sparta’s fate

What becomes of Sparta after its hegemony shatters in 371, after Philip II humiliates it in 338 and after Antipater crushes it in 330? This is a part of Spartan history we don’t much discuss, but it provides a useful coda on the Sparta of the fifth and fourth century. Athens, after all, remained a major and important city in Greece through the Roman period – a center for commerce and culture. Corinth – though burned by the Romans – was rebuilt and remained a crucial and wealthy port under the Romans.

What became of Sparta?

In short, Sparta became a theme-park. A quaint tourist get-away where wealthy Greeks and Romans could come to look and stare at the quaint Spartans and their silly rituals. It developed a tourism industry and the markets even catered to the needs of the elite Roman tourists who went (Plutarch and Cicero both did so, Plut. Lyc. 18.1; Tusc. 5.77).

In term of civic organization, after Cleomenes III’s last gasp effort to make Sparta relevant – an effort that nearly wiped out the entire remaining Spartiate class (Plut. Cleom. 28.5) – Sparta increasingly resembled any other Hellenistic Greek polis, albeit a relatively famous and also poor one. Its material and literary culture seem to converge with the rest of the Greeks, with the only distinctively Spartan elements of the society being essentially Potemkin rituals for boys put on for the tourists who seem to be keeping the economy running and keeping what is left of Sparta in the good graces of their Roman overlords.

Thus ended Sparta: not with a brave last stand. Not with mighty deeds of valor. Or any great cultural contribution at all. A tourist trap for rich and bored Romans.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: This. Isn’t. Sparta. Part VII: Spartan Ends”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-09-27.

March 5, 2023

Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and the Greek Myths

toldinstone

Published 20 Aug 2021Did dinosaur fossils inspire the mythical griffin? Did mammoth bones shape the story of the Gigantomachy? Were the cyclopes modeled on the skulls of dwarf elephants? This video investigates some of the fascinating intersections between fossils and the Greek myths.

This video is part of a collaboration with @NORTH 02 Check out their video “Scimitar Cats, Cave Bears, and Behemoths” for more on the fossils that so fascinated the ancient Greeks and Romans: https://youtu.be/lpU-F3EQ4v4

(more…)

February 22, 2023

Mosquito Bombers Bust Out French Resistance – War Against Humanity 098

World War Two

Published 21 Feb 2023Across Europe the anti-Nazi Resistance continues to rise as does the infighting. In France the RAF carry out Operation Jericho to break out captured resistance members held at the prison in Amiens.

(more…)