… a large bureaucracy will, in approximately 100 percent of cases, become extremely wasteful, and essentially corrupt. It will perpetuate the “problem” that it was founded to solve, and at its most creative, invent new and quite imaginative evils. It will become a vested interest — an “economic player” in its own right — and spread, like a cancer, well beyond the flesh it first inhabited. Any attempt to restrain it will then engender new bureaucracies. The idea of a “humane” bureaucracy is a contradiction of terms. There is no such thing.

Gentle reader must understand that I am not speaking only of “guvmint”, but of bureaucracy, at large. The thing is not necessarily a government department. Any big corporation will quickly show symptoms. The only difference between “public” and “private” is in longevity. A private bureaucracy will kill its host, but thanks to the power of taxation, a public bureaucracy can be long sustained. It is also backed by law and police action, which even today is more effective than mere pointless rules and regulations. The latter, however, are more nimble in expansion, and prepare the ground for law — the full spiritual stasis.

David Warren, “Austrian schoolboy”, Essays in Idleness, 2019-09-17.

January 21, 2024

QotD: The life-cycle of bureaucracies

January 20, 2024

January 14, 2024

The insane miscarriage of justice in Britain’s Post Office and the courts

The British Post Office (formerly the Royal Mail) has spent the last several years prosecuting many of its own staff for financial skulduggery uncovered by the Post Office’s computer system. Many people have been convicted and punished, yet it now comes to light that the real culprit is the faulty accounting methods used in the Post Office’s Horizon software:

“Atten-SHUN! EIIR Red Pillar Boxes” by drivethr? is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 .

What went wrong at the Post Office over that Horizon computer system is being described as very difficult, complicated, we’ll never really find out and Whocouddaknowed?

This is not correct. The Post Office knowed, ICL knowed, Fujitsu knowed.

Therefore and thus, as I’ve said before, just Jail Them All. There will be some who will be able to argue their way out on the basis of their innocence and that’s fine, even great. But let’s start with everyone on the right side of the bars.

It’s long been — as I’ve said — common gossip among programmers that the base problem really was pretty base. The Horizon system counted incompletes as a transaction. So, a transaction is going through and it doesn’t quite make it. Communication problems, something. A sensible system looks at incompletes and ignores them. Only completes, fully handshaken and agreed, change the accounting ledgers. Horizon did not do this. It would count the incomplete as one transaction, then when the full one came through count that as an additional, extra, transaction.

This is how a branch thought it had one number, the centre another. Because the branch regarded the incomplete and the resend as only the one transaction, the centre as two.

But common gossip among programmers isn’t enough, obviously.

It’s bad enough that glitchy software could cause such human tragedy, but it’s worse: Post Office management knew and chose to cover it up.

January 13, 2024

QotD: Brahmins and Mandarins

Traditional Hindu society knew hundreds of hereditary castes and subcastes, but all broadly fit into four major “varna” (“colors”, strata):

- Brahmins (scholars, clerisy)

- Kshatriya (warriors, rulers)

- Vaishya (traders, skilled artisans)

- Shudras (farmers)

- The un-counted fifth varna are the Dalit (“untouchables”, outcasts in both senses of the word)

Historical edge cases aside, membership in the Brahmin stratum was hereditary, even more so than in the nobility of feudal Europe. At least there, kings might raise a commoner to a knighthood or even the peerage for merit or political expedience: one need not wait for reincarnation into a higher caste.

The Sui dynasty in China, however, took a different route. Seeking both to curb the power of the hereditary nobles and to broaden the available talent pool for administrators, they instituted a system of civil service examinations. With interruptions (e.g. under the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan) and modifications, that system remained in place for thirteen centuries until finally abolished in 1904. Westerners refer to laureates of the Imperial Examinations (from the entry-level shengyuan to the top-level jinshi) by the collective term Mandarins. Ironically, this term comes not from any Chinese dialect but (via Malay and Portuguese) from the Sanskrit word mantri (counselor, minister) — cf. the Latin mandatum (command) and its English cognate “mandate”.

Initially, the exams were limited to the scholar and yeoman farmer classes: with time, they were at least in theory opened up to all commoners in the “four occupations” (scholars, farmers, artisans, merchants), with jianmin (those in “base occupations”) still excluded. The process also was ostensibly fair: exams were written, administered at purpose-built examination halls with individual three-walled examination cubicles to eliminate cribbing. Moreover, exam copies were identified by number rather than by name. […]

In practice, the years of study and the costs of hiring tutors for the exam limited this career path to the wealthy. Furthermore, the success rate was very low (between 0.03% and 1%, depending on the source) so one had better have a fallback trade or independent wealth. In some cases, rich families who for some reason were barred from the exams would sponsor a bright student from a poor family. Once the student became a government official, he would owe favors to the sponsor.

Moreover, the subject matter of the exam soon became ossified and tested more for conformity of thought, and ability to memorize text and compose poetry in approved forms, than for any skill actually relevant to practical governance. (Hmm, artists or scholars in a narrow abstruse discipline being touted as authorities on economic or foreign policy: verily, there is nothing new under the sun.)

Nitay Arbel, “Brahmandarins”, According to Hoyt, 2019-10-08.

December 13, 2023

November 30, 2023

The challenge facing Javier Milei

Craig Pirrong outlines just how much work Argentinian President-Elect Javier Milei will have to accomplish to begin to bring Argentina’s government in line with his electoral mandate:

When I wrote Milei is not a leftist, let’s say that rather understates the matter. Milei loathes leftists and leftism, and repeatedly refers to them on television and in public appearances in scatalogical terms, calling them “leftards”. He despises collectivism, and asserts bluntly that leftists are out to destroy you. His mission is to destroy them first.

As someone so vehemently hostile to the left and well outside conventional political categories, Milei’s victory has triggered a mass moral panic, especially in the media. The New York Times coverage was (unintentionally) hilarious: “Some voters were turned off by his past outbursts and extreme comments over years of work as a television pundit and personality.” Well, obviously a lot more weren’t, but I guess one has to take solace where one can, eh, NYT?

Milei’s agenda is indeed a radical one, especially for a statist basket case like Argentina. To combat the country’s massive (140 per cent annualised) inflation, Milei says he will dollarise the economy and eliminate (“burn down”) the central bank. He also wants to reduce radically the role of the state in Argentina’s economy. He says he wants to “chainsaw” the government – and emphasises the point by campaigning with an actual chainsaw.

His election on this programme sparked a rally in Argentine financial markets, with government debt rising modestly and stock prices rallying smartly.

Will Milei be able to deliver? Some early commentary has doubted his ability to govern based on the fact that his party’s representation in the legislature is well below a majority. That may be an issue, but not the major obstacle to Milei’s ability to transform Argentina into what it was at the dawn of the 21st century: an advanced, rapidly growing economy and a relatively free society.

The real obstacle is one that is faced by anti-statists everywhere – the bureaucracy. (I do not say “civil service” because that phrase is at best aspirational and more realistically a patent falsehood. Akin to the Holy Roman Empire that was neither holy nor Roman, the “civil service” is neither civil nor a service.)

Argentina’s bloated state is its own clientele with its own interests, mainly self-preservation and an expansion of its powers. Moreover, it has created a whole host of patronage clients in business and labour. Milei’s agenda is anathema to this nexus of public and private interests. They will make war to the knife to subvert it.

Even a president with an electoral mandate faces formidable obstacles to implementing his agenda. The most important obstacle is what economists call an “agency problem”. The bureaucrats are agents of the chief executive, but it can be nigh unto impossible to get these agents to implement the executive’s directives if they don’t want to. Their incentives are not aligned with the executive, and are often antithetical. As a result, they resist and often act at cross purposes with the executive.

The modern chief executive’s power to force his bureaucratic agents to toe the line is severely circumscribed. At best, the executive can make appointments at the upper levels of the bureaucracy (such as the heads of ministries or departments), but the career bureaucrats who can make or break the executive’s policy are beyond his reach, and not subject to any punishment if they subvert the executive’s agenda.

November 15, 2023

November 10, 2023

Only a government could waste this much money on the ArriveCAN boondoggle

Chris Selley is in two minds about the ArriveCAN scandal, in that thus far no minister has been implicated but we all may naively assume that the civil service was better than this sort of sleaze:

It’s tempting to want to forget that ArriveCAN, the federal government’s pandemic travel app that collected dead-simple information from arriving travellers and forwarded it to relevant officials for scrutiny, and that somehow cost $54.5 million — a figure no one has come within 100 miles of justifying, and don’t let anyone tell you differently. No one wants to remember the circumstances that supposedly made ArriveCAN necessary.

One could also certainly argue there are aspects of Canada’s pandemic response more desperately needing scrutiny. So, so many aspects.

But whenever the House of Commons operations committee sits down to investigate ArriveCAN, there are fireworks. And you start to think, maybe this godforsaken app is more key to understanding Canada’s pandemic nightmare than you first thought.

The latest blasts came on Tuesday, when Cameron MacDonald, director-general of the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) when the pandemic hit, alleged Minh Doan, then MacDonald’s superior and since promoted to chief technological officer of the entire federal government — pause for thought — had lied to the committee on Oct. 24 with respect to who picked GCStrategies to oversee the ArriveCAN project.

Doan told the committee he hadn’t been “personally involved” in the decision. MacDonald, who says he had recommended Deloitte build the app, says that’s garbage. “It was a lie that was told to this committee. Everyone knows it,” he said. “Everyone knew it was his decision to make. It wasn’t mine.” MacDonald said Doan had threatened in a telephone conversation to finger him as the culprit, and that he had felt “incredibly threatened”.

Crikey.

For those who’ve blissfully forgotten, GCStrategies consists of two people who subcontract IT work to teams of experts and takes a cut off the top — in this case a cut of roughly $11 million, for an app that should have cost a fraction of that, if it was to exist at all. Needless to say, that wasn’t the only fat contract GCStrategies — which, again, is two men and an address book — had received from the government over the years. Each GCStrategist made more money off ArriveCAN than I’ll likely make in my life. It makes me want to strap on a bass drum and sing “The Internationale” in public.

November 9, 2023

QotD: The end of the “spoils system” and the professionalization of the bureaucracy

… There was, however, one last check on the power of faction: The bureaucracy.

I know, that seems weird, but unless you’ve really studied this stuff — it’s not taught in most high school or even college classes, for some mysterious reason — you probably don’t know that the civil service used to be entirely patronage-based. Our two most famous literary customs inspectors, for instance (Hawthorne and Melville), got their jobs through political connections, and that’s the way it worked for everyone — every time the other party won an election, most of the bureaucrats got turfed out, to be replaced by loyal party men. Trust me: very few of the names on this list would ring much of a bell even to field specialists, but they were big political cheeses in their day; Postmaster General was a plum federal post that was often handed to loyal Party men as a reward for a lifetime of faithful service. And so on down the line, including your local postmaster.

It took until 1883 to finally kill of this last vestige of federalism, but the Pendleton Act did it. Here again, this isn’t taught in school for some mysterious reason, but the political class took a very different lesson from the Civil War than the hoi polloi. While for the proles the Civil War was presented as a triumph of the common man, the elite understood that it was training, logistics, bureaucratization, professionalism that won the war for the Union. The Republicans made a big show of putting up U.S. Grant as “the Galena Tanner” in their campaign rhetoric but Grant had been a bankrupt tanner, and indeed a conspicuous failure at everything except war … and even there, his record was carefully doctored to present an image of a bumbling amateur suddenly being struck by inspiration, when in fact Grant was a West Pointer with an impressive combat record in the Mexican War. Now is not the time or place to discuss the merits, or not, of various Civil War figures, so just go with me on this: Pretty much all the big name generals on both sides of the war were presented to the public as talented gentleman amateurs, and it was heavily insinuated that the ones they couldn’t so portray — McClellan, and especially Robert E. Lee — lost because they were too hidebound, too “professional”.

The reality is almost the complete opposite — yeah, Stonewall Jackson ended the Mexican War as a mere captain (no mean feat in The Old Army, but whatever), but he had a tremendous combat record, and was so much of a military professional that he actually taught at a military academy. This is not to say there weren’t naive geniuses in the Civil War — see e.g. Nathan Bedford Forrest — but the Civil War, like all wars since the invention of the arquebus, was won by hardcore, long-service, well-trained professionals. A naive genius like Forrest might’ve been a better tactician, mano-a-mano and in a vacuum, than a West Point professional like Custer — then again, maybe not — but wars aren’t fought in vacuums. They’re fought on battlefields, and they’re won by supply weenies and staff pogues.

[…]

They took that experience with them into politics, and so it’s no surprise that the Federal government of the Gilded Age, though tiny by our standards, grew into such a leviathan in so short a time. Again, I’m just going to have to ask you to trust me on this, since for some reason it never gets covered in school, but back in the later 19th century words like “efficiency” really meant something to the political class. All those politician-generals (and politician-colonels and politician-majors and all the rest down at the local level) expected the State to function like the Army — that is to say, as a self-enclosed world where efficiency not only counts, but triumphs. An amateur civil service can’t do that, and so the days of the political sinecure had to end.

Severian, “Real Federalism Has Never Been Tried”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-05-03.

November 5, 2023

QotD: The Auftragstaktik principle of the Third Reich

[The Nazis], being Social Darwinists to the core, applied the military principle of Auftragstaktik to civilian life. “Mission-oriented” tactics means that the overall commanders leave as much as possible to the on-the-spot commanders, be they officers or noncoms, on the theory that properly-trained leaders will have a much better understanding of what needs to be done, and how to do it, than some general back at HQ. It’s the main reason the Wehrmacht could keep fighting so well, for so long, in the face of overwhelming opposition — tasks that would fall to an American company, or a Russian regiment, were often undertaken by a Wehrmacht platoon under the command of a senior corporal.

Obviously civilian life isn’t as goal-directed as the military in wartime, but a similar principle applied — given a vague set of generalized objectives from the top (Kershaw’s famous “working towards the Führer” thesis), everyone at every level was encouraged to move the ball downfield as he saw fit … with the added twist that, in the absence of a clearly defined, military-style chain of command, the various “subordinates” would ruthlessly battle it out with each other, Darwin-style, for bureaucratic supremacy.

Thus the Nazis’ infamous plate-of-spaghetti org charts. I’m not an expert, but I’m pretty sure there were more than a few guys who held wildly different ranks in various different organizations simultaneously. He might be a mere patrolman in the Order Police, but an officer in the SS, a noncom in the SA (you could be in both, at least in the early days), and so forth. I wouldn’t be surprised if there was more than one guy who technically reported to himself, somewhere deep in the bowels of the RHSA [Reich Security Main Office]. You could spend a lifetime trying to sort this stuff out …

Severian, “The Crisis of the Third Decade”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-03-18.

October 29, 2023

Arguments for not buying military kit “off the shelf”

Sir Humphrey provides some of the reasons why it’s not a simple economic case for a nation’s military procurement to buy “off the shelf” equipment even from a close ally:

Not all kit needs to be or can be domestically sourced. The British army uses Apache attack helicopters which are licensed from the original US manufacturer.

Westland Apache WAH-64D Longbow helicopter (UK Army registration ZJ206) displays at Kemble Air Day 2008, Kemble Airport, Gloucestershire, England in June 2008.

Public domain photograph by Adrian Pingstone.

The arguments for buying American are on the face of it reasonable. The US produces good quality equipment able to meet many UK defence needs. There is a strong supply chain in place, ensuring that there are plenty of spare parts in the system to draw on when needed, and at cheaper cost due to bulk buying. The equipment is usually designed to be interoperable with NATO partners, so it can be integrated to work alongside allies and with existing equipment. It can be delivered quickly, it works and lots of other people use it, so why shouldn’t the UK? There are in fact many good reasons why the UK should not exclusively buy American.

Earlier this month, we looked at the Canadian Surface Combatant (CSC) program and why the Canadian Armed Forces never seemed to get the same “bang for the buck” that our American or British allies seem to manage. Here, Sir Humphrey points out that even the British military has to make procurement decisions that weigh cost and convenience with some very significant national security concerns:

To start with, US kit is designed by US companies to meet US requirements, not British ones. This may sound obvious but there is a dangerous view some put forward that “off the shelf” means the UK could just buy something and use it. There is no such thing as “off the shelf” unless you want it as it comes in its US version, with no modifications, changes or installation of British equipment. The moment you do this, you’ve created a UK variant with its own bespoke requirements and supply needs, for which you are dependent on the US defence industry to support – and there is no guarantee that this can or will happen. From the outset you have lost operational sovereignty and control over your military equipment.

Buying from the US means the UK would need to request a Foreign Military Sale (FMS) case through the US government, seeking legislative approval to purchase the equipment. If, for example, the UK wanted to buy a new tank, it would be reliant on US government approval to do so, not just for the initial purchase, but for all spares buy thereafter. The way that FMS works is that it sets out approval not just for purchase, but sets a schedule for spare parts purchases, services, and upgrades, all of which are done at the time and schedule set by US government and industry, and not the British government. This means that the UK would lose control over when to purchase spares or upgrades and would be forced to buy to a foreign governments timetable. This is why FMS is so successful for the US – it offers cheap entry prices but makes a killing in the long-term spares and support market. To buy from the US means to accept that you are handing over control of your spares and logistics chain to a foreign power who determines the timing of when and what you buy. This is fine in small doses but if you buy exclusively from the US, suddenly means you’ve got no control over how you want to support your armed forces.

The next challenge is the integration work needed to make things work for the UK. One of the risks of buying a foreign design is that you lack operational sovereignty over the design and its internal contents. Equipment supplied by the US will often come with a variety of sealed, tamper proof boxes containing US government-controlled technology that cannot be accessed by the purchasing nation. As the operator, you do not have full control over your military equipment, you don’t know what is necessarily in the boxes, and you are reliant on the US to fix issues with them. By contrast any equipment designed and built in the UK means that the MOD has full control and sovereignty over it to open it up, modify, adapt or change it to meet British needs. To buy US means accepting we cannot change a design without a foreign nations’ approval, which in turn means exposing our own sensitive military technology and equipment to the US, to conduct trials to ensure it can work with the US provided equipment. This represents an astounding loss of sovereign control on advanced weapon systems and means potentially giving the US defence industry insight into UK capabilities that manufacturers may want to keep commercially sensitive.

October 26, 2023

October 25, 2023

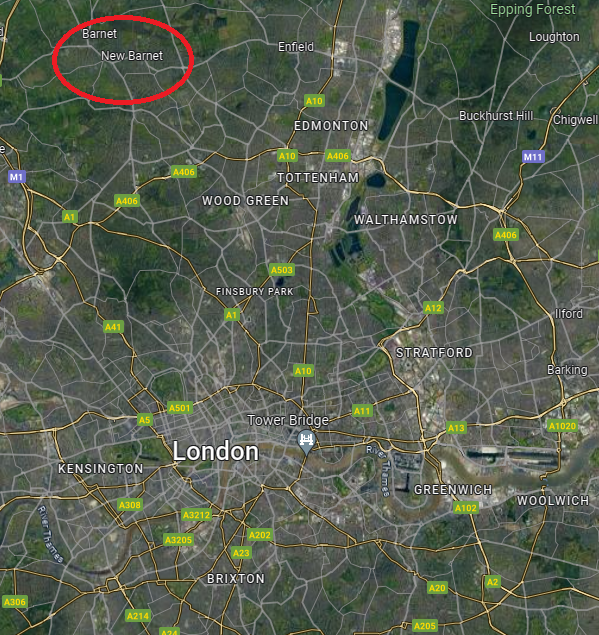

Housing for Hamas leadership … in London

In the non-paywalled part of a post from Ed West, we have a look at the terrible conditions leaders for Hamas and other terrorist organizations have to put up with in the embattled suburbs of … London:

Barnet, to those unfamiliar with this corner of the world, is the most Jewish borough in Britain, an area of north-west London often described as “leafy” and including both pleasant inner suburbs like Finchley as well as areas of genuine countryside. The migration of eastern European Jews in the capital followed an anticlockwise direction from impoverished Whitechapel in east London up through Hackney and Haringey in the north, with Barnet the next stop.

It is also, strangely, home to a leading fundraiser for Hamas, the terrorist group responsible for the murder of 1,400 people in southern Israel earlier this month and quite explicitly committed to the eradication of Jews in the Holy Land.

What with London house prices being what they are, you wonder how he managed it, but of course Muhammad Qassem Sawalha, who “ran the group’s terrorist operations in the West Bank”, according to the Sunday Times, managed to buy his property with help from the council.

Despite being a known and wanted terrorist, Sawalha was allowed to settle in Britain in the 1990s and obtain British citizenship. He continued to work for Hamas, holding talks about committing terrorist acts and laundering money for the group, according to the US Department of Justice. In 2009 he signed the Istanbul Declaration which praised God for having “routed the Zionist Jews”, and called for a “Third Jihadist Front” to be “opened in Palestine alongside Iraq and Afghanistan”, according to the paper.

All the while he was benefitting from Britain’s social housing system. In 2003, Barnet Council made him a council tenant and he was housed in a two-storey property with a garden and garage in the borough, where he still lives.

Two years ago, Sawalha and his wife used the Right to Buy scheme to acquire their home for £320,700, with Barnet Council giving them a £112,300 discount on its market value.

This is despite the fact that in 2006 Panorama reported that Sawalha was “said to have masterminded much of Hamas’ political and military strategy” and that, “although he was known to MI5, the ‘authorities let him operate freely here'”. Not just let him operate freely, but sort him out with a house – and if you think this sounds insane, it is not at all uncommon.

Sawalha’s old comrade, the famous hook-handed hate preacher Abu Hamza, was also given a huge house courtesy of the British taxpayer. The Egyptian was allowed to live rent-free in a five-bedroom house in what the Mail described as “upmarket Shepherd’s Bush”, a phrase I would have found astonishing to read as a teenager in west London.

Shepherd’s Bush is next door to super-rich Holland Park, and private property is extremely expensive there – but it also has high levels of social housing, as with much of central London, so “upmarket” might be stretching it.

October 22, 2023

A lawyer in “deep blue” Pennsylvania discovers that elected bodies don’t have to listen to the voters

Chris Bray on the details of a case from Pennsylvania where an active and involved parent tried to get answers from the elected school board on how they justified imposing masking requirements without a shred of legal power to do so:

In December of 2021, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that officials in that state had implemented mask mandates that they had no legal authority to impose. The decision in Corman v. Beam is not written in stirring language, and makes no bold declarations about truth, freedom, and the American way; it’s a workmanlike examination of statutory language, quite dull to read. Test me on that characterization, if you want. But the court concluded, importantly, that the mandate had been invalid ab initio — not from the moment the court struck it down, but rather from the moment it was issued. Mask mandates had never been enforceable in Pennsylvania.

In an affluent, deep blue community in the Philadelphia suburbs, a lawyer and parent named Chad Williams took the ruling as vindication. With four children in the local schools, he’d been telling school officials — clearly and often — that they had no legal authority to require masks on campus. To say that they hadn’t listened would be an understatement.

In August of 2020, during a Zoom meeting to decide on in-person school for the soon-to-begin school year, the nine-member Unionville-Chadds Ford school board muted Williams when he asked about the legal basis for the choice.

Repeating the performance, school board members cut the microphones and walked out of one of their own subsequent meetings, in August of 2021, to avoid listening to Williams when he didn’t stop speaking at the three-minute mark during their public comment session. Other parents concerned about forced masking for children received a similarly warm reception. The school board voted unanimously that same night to again impose a mask mandate on their campuses for the new school year.

For Williams, the repeated experience was a shock. He was an experienced lawyer, a parent, an established member of the community, and a volunteer coach at the high school — and he couldn’t get anyone to listen to a reasonable question. He asked his school board to explain the legal basis for a new policy, and “the school board president just cut me off.” Officials were acting in lockstep, without apparent authority, and refusing to explain their choices. “They just wouldn’t answer,” Williams says. Many of us have had this experience.

The school district finally dropped its mask mandate in March of 2022, after the decision from the state Supreme Court. And that was the end — except for one thing. A formal policy of the Unionville-Chadds Ford School District, Policy 906, establishes “a fair and impartial method” for the examination of parent complaints. You can find that policy here, in the section labeled “Community”. The policy is detailed and unambiguous, and starts requiring written reports after the failure of early and informal stages of resolution:

Third Level – If a satisfactory solution is not achieved by discussion with the building principal or immediate supervisor, a conference shall be scheduled with the Superintendent or designee. The principal or supervisor shall provide to the Superintendent or designee a report that includes the specific nature of the complaint, brief statement of relevant facts, how the complainant has been affected adversely, the action requested, and the reasons why such action should be taken or not taken.

Fourth Level – Should the matter not be resolved by the Superintendent or designee or is beyond his/her authority and requires Board action, the Superintendent or designee shall provide the Board with a complete report.

Final Level – After reviewing all information relative to the complaint, the Board shall provide the complainant with its written decision and may grant a hearing before the Board or a committee of the Board.

Williams used Policy 906 to ask the school board to think about what it had done, conducting an independent review of its policy decisions during the pandemic. Why had school officials implemented policies they had no legal authority to impose? Why had they refused to discuss or address parent questions? Why had they stonewalled requests for documents and information — not only from parents, but from a state senator who took an interest in the matter? Williams asked for an apology and “changes in oversight” to prevent a recurrence of unlawful and unexplained policy decisions, using formal school district policy that requires the district to act on complaints.

They haven’t bothered. The Unionville-Chadds Ford School District continues to ignore Williams, not responding to his complaints or opening the inquiry their own policy requires them to pursue. He’s had one sort-of response: In an exchange over the handling of the complaint, the district’s lawyers, at a private law firm, threatened him with legal action — a threat they so far haven’t made good. But from school district officials, the only response to three years of questions is unbroken silence.

October 19, 2023

The evisceration of Bill C-69 (aka the Impact Assessment Act)

The decision of the Supreme Court of Canada to strike down large parts of the federal Impact Assessment Act caught a lot of people by surprise. The court hasn’t made much of a habit of rejecting the federal government’s ever-increasing encroachments on provincial jurisdiction, so this ruling is a bit of a black swan. It’d be nice if the Supremes were going to be more vigilant in future, but that’s unlikely. Colby Cosh explains why this is a “remarkable political moment”:

To hear the Liberals talk now, you would think that the Supreme Court’s 7–2 rebuke of C-69 was a mere bump in the road. Steven Guilbeault, the federal environment minister, appeared on CTV’s Question Period to reassure the public that the law can be “redefined” to accomplish its grandiose intentions; it’s just a matter of “course-correct(ing)” the text a smidgen in order to “comply with the spirit” of the ruling.

Here’s an idea for the minister: maybe just go ahead and comply with the ruling, period?

Comply with the spirit, he says. Having taken the trouble to decrypt the ruling, which is not exactly a masterpiece of lucid clarity, I wonder at the environment minister’s priorities. Rather than appearing on television with a bunch of happy talk, he ought to have been mopping up the seas of blood left by the court’s evisceration of his Impact Assessment Act.

In essence, the Liberals created an apparatus whereby a federal panel would perform environmental and social assessments of major infrastructure projects based on the possibility that they might “cause adverse effects within federal jurisdiction”.

The underlying pretext is that the federal government’s powers are sometimes engaged by the creation of mines, wells, roads and other such projects — even when they are confined within one province’s borders — because they can conceivably affect federal matters such as fisheries, migratory birds, Aboriginal welfare, treaty obligations and other “national concerns”.

This is true as far as it goes, but the court majority’s finding was that this constitutional pretext for creating a federal assessment scheme isn’t actually reflected in the scheme itself. The Liberals, asserting a right to investigate hypothetical infringements on the federal sphere of power, created a law that essentially allows them to veto anything that a province might want to permit.

As the law is written, the initial assessment-agency decision to “designate” a project for assessment can be based on just about anything, including “any comments received … from the public” and “any other factor the Agency considers relevant”. In the final decision-making phase, which is to be based on the “public interest”, specific federal heads of power are also cast aside: whoever makes the final call at the cabinet level is to evaluate a project for “sustainability”, for example.