Extra Credits

Published on 27 Jan 2018She was the most ferocious pirate China had ever known. She was a powerful fleet commander, a sharp businesswoman, and a consummate strategist. She was Cheng I Sao, leader of the Pirate Confederation, and she lived her life on her terms.

January 29, 2018

Cheng I Sao – Pirate Queen – Extra History

January 21, 2018

Sun Tzu – The Art of War l HISTORY OF CHINA

IT’S HISTORY

Published on 8 Aug 2015Sun Tzu’s The Art of War is a book on military strategies written around 500 BC, between the collapse of the Zhou dynasty and the rise of the first emperor of imperial China. Today Tzu’s guidelines are still as applicable as ever. They are still being read by military commanders, politicians and businesspeople all over the world. Also known as “Master Sun’s Military Methods”, the book explains basics like the “Strategy of Attack”, “Moving the Army” and even “Employing Spies” in 13 short chapters, restricting itself to general principles rather than detailed instructions of strategy and tactics. Learn all about this timeless and influential military masterpiece on IT’S HISTORY.

January 14, 2018

December 27, 2017

India’s Geography Problem

Wendover Productions

Published on 5 Dec 2017

December 21, 2017

Manufacturing model trains in China

Jason Shron (who glories in living the “hoser” stereotype) runs a small Canadian company that manufactures 1:87 scale model trains, doing the majority of the actual manufacturing in China. Even there, rising standards of living mean that small companies like Rapido Trains need to be on the lookout for ways to economize, as illustrated in this short video:

The bloody 20th century and the leaders who helped make it so

Walter Williams on the terrible death toll of the 20th century, both in formal war between nations and in internal conflict and repression:

The 20th century was mankind’s most brutal century. Roughly 16 million people lost their lives during World War I; about 60 million died during World War II. Wars during the 20th century cost an estimated 71 million to 116 million lives.

The number of war dead pales in comparison with the number of people who lost their lives at the hands of their own governments. The late professor Rudolph J. Rummel of the University of Hawaii documented this tragedy in his book Death by Government: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900. Some of the statistics found in the book have been updated here.

The People’s Republic of China tops the list, with 76 million lives lost at the hands of the government from 1949 to 1987. The Soviet Union follows, with 62 million lives lost from 1917 to 1987. Adolf Hitler’s Nazi German government killed 21 million people between 1933 and 1945. Then there are lesser murdering regimes, such as Nationalist China, Japan, Turkey, Vietnam and Mexico. According to Rummel’s research, the 20th century saw 262 million people’s lives lost at the hands of their own governments.

Hitler’s atrocities are widely recognized, publicized and condemned. World War II’s conquering nations’ condemnation included denazification and bringing Holocaust perpetrators to trial and punishing them through lengthy sentences and execution. Similar measures were taken to punish Japan’s murderers.

But what about the greatest murderers in mankind’s history — the Soviet Union’s Josef Stalin and China’s Mao Zedong? Some leftists saw these communists as heroes. W.E.B. Du Bois, writing in the National Guardian in 1953, said, “Stalin was a great man; few other men of the 20th century approach his stature. … The highest proof of his greatness (was that) he knew the common man, felt his problems, followed his fate.” Walter Duranty called Stalin “the greatest living statesman” and “a quiet, unobtrusive man.” There was even leftist admiration for Hitler and fellow fascist Benito Mussolini. When Hitler came to power in January 1933, George Bernard Shaw described him as “a very remarkable man, a very able man.” President Franklin Roosevelt called the fascist Mussolini “admirable,” and he was “deeply impressed by what he (had) accomplished.”

December 9, 2017

The Trudeau sideshow in China

Colby Cosh on figuring out why Justin Trudeau’s trip to China didn’t end in the glory he and his handlers were clearly anticipating:

My favourite part of the fair has always been the sideshow. And when it comes to Justin Trudeau’s official visit to China, the sideshow definitely turned out to be the most interesting part of the proceedings. Interpreting the outcome of the visit involves a certain amount of old-fashioned Kremlinology, applied to both sides, but it seems fairly clear that Trudeau was gulled into providing Chinese leadership with some celebrity glamour in exchange for a big pile of nothing on Chinese-Canadian trade.

He came to China with hopes for progress on a future trade deal that would involve China accepting new labour, gender, and environment standards. But he collided with the newly aggressive Xi Jinping doctrine — a change in the official Chinese mood that insists on the country’s superpower status. China-watchers know that over the past year, in a process that culminated at the 19th Chinese Communist Party Congress in October, China has become more explicit, and more chauvinist, in claiming to pursue an independent, indigenous alternative model of economic and social progress.

[…]

Western commentators on China have, for a long time, had an implicit vision of a re-emerging bipolar world, with China in the old place of Russia as an ideological challenger to Western democracies. Xi is taking them at their word. China’s aspirations are no longer to follow or imitate the West, but to out-compete it on its own terms, without any of the untidy, politically dis-unifying elements of Western life — independent universities, newspapers that aren’t trash, multiple political parties, and the like.

Given this background, Trudeau arguably arrived in China at exactly the wrong moment. Formal talks on a China-Canada free trade agreement would have been the first ever between China and a G7 country. It turned out that there was more value for Xi in slapping the hand of friendship. The Global Times, an organ of the party’s People’s Daily newspaper network, published a cranky English-language editorial in the midst of Trudeau’s visit.

The editorial attacked the “superiority and narcissism” of Canadian newspapers, as an alternative to jabbing the prime ministerial guest in the eye personally. But it is easy enough to read between the lines. “Trade between China and Canada is mutually beneficial, more significant than the ideology upon which the latter’s media has been focusing,” wrote the tabloid’s editor, Hu Xijin. “When Canada imports a pair of shoes from China, will Canada ask how much democracy and human rights are reflected in those shoes?”

If Trudeau had been hoping to wipe away memories of his embarrassing stunt at the TPP negotiations by a Pierre-Trudeau-like Chinese breakthrough, the Chinese government clearly saw him coming a few thousand miles away and ensured that no such PR coup would be allowed.

November 27, 2017

China discovers that there’s a (very) limited appetite for shared bikes

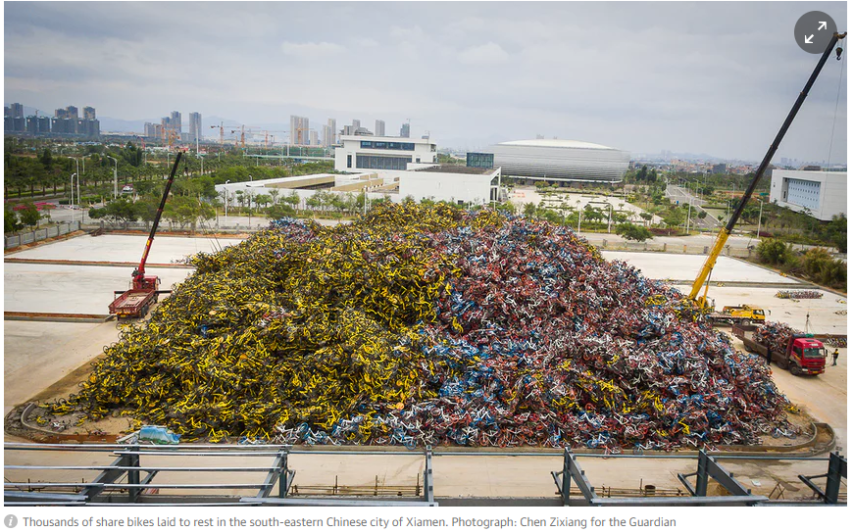

In the Guardian, Benjamin Haas reports on what at first might seem to be a vast modern art display:

At first glance the photos vaguely resemble a painting. On closer inspection it might be a giant sculpture or some other art project. But in reality it is a mangled pile of bicycles covering an area roughly the size of a football pitch, and so high that cranes are need to reach the top; cast-offs from the boom and bust of China’s bike sharing industry.

Just two days after China’s number three bike sharing company went bankrupt, a photographer in the south-eastern city of Xiamen captured a bicycle graveyard where thousands have been laid to rest. The pile clearly contains thousands of bikes from each of the top three companies, Mobike, Ofo and the now-defunct Bluegogo.

Tim Worstall draws the correct conclusion from the provided evidence:

We want, irrespective of anything else about the economy, a method of testing ideas to see if they work. Does the application of these scarce resources meet some human need or desire? Does it do so more than an alternative use, is it even adding value at all?

Bike shares, are they a good idea or not? The underlying problem being that expressed and revealed preferences aren’t the same. There’s only so far market research can take you, at some point someone, somewhere, has to go out and do it and see.

Excellent, the Commie Chinese have done so. Vast amounts of capital thrown into this, competing bike share companies, hire costs pennies. And no fucker seems very interested. That is, no, large scale bike share schemes don’t meet any discernible human need or desire, they don’t add value, spending the money on something else will increase human joy and happiness better.

And this is excellent, we’ve tried the idea and it don’t work. Now we can abandon it and go off and do something else therefore.

Which is the great joy of market based systems. They’re the best method we’ve got of finding out which ideas are fuck ups.

Long live markets.

November 4, 2017

June 4, 2017

Intro to the Solow Model of Economic Growth

Published on 28 Mar 2016

Here’s a quick growth conundrum, to get you thinking.

Consider two countries at the close of World War II — Germany and Japan. At that point, they’ve both suffered heavy population losses. Both countries have had their infrastructure devastated. So logically, the losing countries should’ve been in a post-war economic quagmire.

So why wasn’t that the case at all?

Following WWII, Germany and Japan were growing twice, sometimes three times, the rate of the winning countries, such as the United States.

Similarly, think of this quandary: in past videos, we explained to you that one of the keys to economic growth is a country’s institutions. With that in mind, think of China’s growth rate. China’s been growing at a breakneck pace — reported at 7 to 10% per year.

On the other hand, countries like the United States, Canada, and France have been growing at about 2% per year. Aside from their advantages in physical and human capital, there’s no question that the institutions in these countries are better than those in China.

So, just as we said about Germany and Japan — why the growth?

To answer that, we turn to today’s video on the Solow model of economic growth.

The Solow model was named after Robert Solow, the 1987 winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics. Among other things, the Solow model helps us understand the nuances and dynamics of growth. The model also lets us distinguish between two types of growth: catching up growth and cutting edge growth. As you’ll soon see, a country can grow much faster when it’s catching up, as opposed to when it’s already growing at the cutting edge.

That said, this video will allow you to see a simplified version of the model. It’ll describe growth as a function of a few specific variables: labor, education, physical capital, and ideas.

So watch this new installment, get your feet wet with the Solow model, and next time, we’ll drill down into one of its variables: physical capital.

Helpful links:

Puzzle of Growth: http://bit.ly/1T5yq18

Importance of Institutions: http://bit.ly/25kbzne

Rise and Fall of the Chinese Economy: http://bit.ly/1SfRpDL

May 26, 2017

Puzzle of Growth: Rich Countries and Poor Countries

Published on 16 Feb 2016

Throughout this section of the course, we’ve been trying to solve a complicated economic puzzle — why are some countries rich and others poor?

There are various factors at play, interacting in a dynamic, and changing environment. And the final answer to the puzzle differs depending on the perspective you’re looking from. In this video, you’ll examine different pieces of the wealth puzzle, and learn about how they fit.

The first piece of the puzzle, is about productivity.

You’ll learn how physical capital, human capital, technological knowledge, and entrepreneurs all fit together to spur higher productivity in a population. From this perspective, you’ll see economic growth as a function of a country’s factors of production. You’ll also learn what investments can be made to improve and increase these production factors.

Still, even that is too simplistic to explain everything.

So we’ll also introduce you to another piece of the puzzle: incentives.

In previous videos, you learned about the incentives presented by different economic, cultural, and political models. In this video, we’ll stay on that track, showing how different incentives produce different results.

As an example, you’ll learn why something as simple as agriculture isn’t nearly so simple at all. We’ll put you in the shoes of a hypothetical farmer, for a bit. In those shoes, you’ll see how incentives can mean the difference between getting to keep a whole bag of potatoes from your farm, or just a hundredth of a bag from a collective farm.

(Trust us, the potatoes explain a lot.)

Potatoes aside, you’re also going to see how different incentives shaped China’s economic landscape during the “Great Leap Forward” of the 1950s and 60s. With incentives as a lens, you’ll see why China’s supposed leap forward ended in starvation for tens of millions.

Hold on — incentives still aren’t the end of it. After all, incentives have to come from somewhere.

That “somewhere” is institutions.

As we showed you before, institutions dictate incentives. Things like property rights, cultural norms, honest governments, dependable laws, and political stability, all create incentives of different kinds. Remember our hypothetical farmer? Through that farmer, you’ll learn how different institutions affect all of us. You’ll see how institutions help dictate how hard a person works, and how likely he or she is to invest in the economy, beyond that work.

Then, once you understand the full effect of institutions, you’ll go beyond that, to the final piece of the wealth puzzle. And it’s the most mysterious piece, too.

Why?

Because the final piece of the puzzle is the amorphous combination of a country’s history, ideas, culture, geography, and even a little luck. These things aren’t as direct as the previous pieces, but they matter all the same.

You’ll see why the US constitution is the way it is, and you’ll learn about people like Adam Smith and John Locke, whose ideas helped inform it.

And if all this talk of pieces makes you think that the wealth puzzle is a complex one, you’d be right.

Because the truth is, the question of “what creates wealth?” really is complex. Even the puzzle pieces you’ll learn about don’t constitute every variable at play. And as we mentioned earlier, not only are the factors complex, but they’re also constantly changing as they bump against each other.

Luckily, while the quest to finish the wealth puzzle isn’t over, at least we have some of the pieces in hand.

So take the time to dive in and listen to this video and let us know if you have questions along the way. After that, we’ll soon head into a new section of the course: we’ll tackle the factors of production so we can further explore what leads to economic growth.

May 23, 2017

The Ally From The Far East – Japan in World War 1 I THE GREAT WAR Special

Published on 22 May 2017

Japan’s participation in World War 1 is an often overlooked part of their history – even in Japan itself. Their service as one of the members of the Entente marked the climax of a development that started with the Meiji Restoration, a way out of isolation and into the global alliance system. This brought Japan more power and was also very lucrative. And after fighting in the Pacific Theatre of World War 1, the Siege of Tsingtao and contributing the Japanese Navy to the war effort, Japan had a seat at the table of the Versailles peace negotiations.

April 6, 2017

American “isolationism” between the wars

Reason‘s Jesse Walker linked to this article by Andrew Bacevich which helps to debunk the routine description of US foreign policy between the first and second world wars as “isolationism”:

… McCain is worried about the direction of world events, with Russian provocations offering but one concern among many. Patterson shares McCain’s apprehensions, compounded by what he sees as a revival of “the isolationism in Europe and America that precipitated World War II.”

Now as an explanation for the origins of the war of 1939-1945, American “isolationism” is as familiar as the sweet-and-sour pork featured at your local Chinese takeout joint. Its authenticity is equally dubious. Yet Patterson’s assertion has this virtue: It captures in less than a sentence a prime obstacle to instituting a realistic, fact-based approach to foreign policy.

In truth, isolationism is to history what fake news is to journalism. The oft-repeated claim that in the 1920s and 1930s the United States raised the drawbridges, stuck its head in the sand, and turned its back on the world is not only misleading, but also unhelpful. Citing a penchant for isolationism as a defect afflicting the American character is like suggesting that members of Congress suffer from a lack of self-esteem. The charge just doesn’t square with the facts, no matter how often repeated.

Here, by way of illustrating some of those relevant facts, is a partial list of places beyond the boundaries of North America, where the United States stationed military forces during the interval between the two world wars: China, the Philippines, Guam, Hawaii, Panama, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. That’s not counting the U.S. Marine occupations of Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic during a portion of this period. Choose whatever term you like to describe the U.S military posture during this era — incoherent comes to mind — but isolationism doesn’t fill the bill.

As for Patterson’s suggestion that the behavior of the United States “precipitated” World War II, the claim is simply laughable. World War I precipitated World War II, or more specifically the European malaise resulting from the bloodletting of 1914-1918, compounded by the Bolshevik Revolution and the spread of fascism, and further exacerbated by profoundly shortsighted policies pursued by Great Britain and France. Throw into the mix the Great Depression, Japanese imperial ambitions, and the diabolical plotting of Adolf Hitler and his henchmen, and you have the makings of a catastrophe. Some few observers foresaw that catastrophe, but preventing it lay well beyond the ability of the United States, even if U.S. leaders had been clairvoyant.

March 30, 2017

Another Japanese “destroyer” joins the fleet

Due to a long-standing aversion to calling certain kinds of vessels by their most appropriate name, the Japanese Maritime Self-Defence Force (because Japan’s constitution prohibits the country having a “navy”, post-1945) commissioned their latest “destroyer” last week:

JS Izumo DDH-183, sister-ship of the just-commisioned JS Kaga DDH-184, both helicopter-equipped destroyers, officially.

I know what you’re thinking … “That doesn’t look like a destroyer to me” … but that’s what Japan officially designates ships like this to be, so that’s what they’re called. Strategy Page has more:

On March 22nd Japan put into service a second 27,000 ton “destroyer” (the Kaga, DDH 184) that looks exactly like an aircraft carrier. Actually it looks like an LPH (Landing Platform Helicopter) an amphibious ship type that first appeared in the 1950s. This was noted when Izumo, the first Japanese LPH was launched in 2012 (it entered service in 2015). The Izumos can carry up to 28 aircraft and are armed only with two 20mm Phalanx anti-missile cannon and launcher with sixteen ESSM missiles for anti-missile defense.

LPHs had no (or relatively few) landing craft but did carry a thousand or more troops who were moved ashore using the dozen or more helicopters carried. The first American LPH (the USS Iwo Jima) was an 18,400 ton ship that entered service in 1961, and carried 2,000 troops and twenty-five helicopters. Until Izumo showed up, several nations operated LPHs, and Britain and South Korea still do. The U.S. retired its last LPHs in the 1990s, but still have a dozen similar ships that include landing craft (and a well deck in the rear to float them out of) as well as helicopters. A few other nations have small carriers that mostly operate helicopters but carry few, if any troops.

The Izumos are the largest LPHs to ever to enter service. It differs from previous LPHs in not having accommodations for lots of troops and having more powerful engines (capable of destroyer-like speeds of over fifty-four kilometers an hour). Izumo does have considerable cargo capacity, which is intended for moving disaster relief supplies quickly to where they are needed. Apparently some of these cargo spaces can be converted to berthing spaces for troops, disaster relief personnel, or people rescued from disasters. There are also more medical facilities than one would expect for a ship of this size. More worrisome (to the Chinese) is the fact that the Izumo could carry and operate the vertical take-off F-35B stealth fighter, although Japan has made no mention of buying that aircraft or modifying the LPH flight decks to handle the very high temperatures generated by the F-35B when taking off or landing vertically. The Chinese are also upset with the name of this new destroyer. Izumo was the name of a Japanese cruiser that was a third the size of the new “destroyer” and led the naval portion of a 1937 operation against Shanghai that left over two-hundred-thousand Chinese dead. The Chinese remember all this, especially the war with Japan that began unofficially in 1931 and officially in 1937.

IJNS Izumo at anchor 1932 (Colourized), via Wikimedia

How Germany’s Victories weakened the Japanese in World War 2

Published on 24 Mar 2017

This video gives you a short glimpse on how the war in Europe had a detrimental effect on the Japanese Economy.

Military History Visualized provides a series of short narrative and visual presentations like documentaries based on academic literature or sometimes primary sources. Videos are intended as introduction to military history, but also contain a lot of details for history buffs. Since the aim is to keep the episodes short and comprehensive some details are often cut.