Feature History

Published on 25 Jul 2017Hello and welcome to Feature History, featuring a civil war that done happened in China.

Help me recognise Taiwan (or not)

https://www.paypal.me/FeatureHistory

Patreon

https://www.patreon.com/FeatureHistory

Discord

https://discord.gg/Zbk4CvR

———————————————————————————————————–

I do the research, writing, narration, art, and animation. Yes, it is very lonely

September 6, 2018

Feature History – Chinese Civil War

August 23, 2018

It’s quite possible to spend too much on infrastructure

Tim Worstall on the recent cancellation of two large Chinese infrastructure projects in Malaysia:

A working mantra of our times is that we should all be building much, much, more infrastructure. And that it should be government telling us where and what should be built, even going and building it. All of which rather runs into that brick wall of what is happening with China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Yes, it’s entirely true that the old Silk Road was a useful and enriching trade route. It’s equally obvious that other trade routes have had the same effect, enriching. That is not though the same as the statement that building a trade link enriches. A trade route which is used does, one that is built still has to be used to enrich anyone other than the constructors who make off with their pay. The measure of whether the Belt and Road Initiative enriches is whether it is used, not whether it is built.

This being something that the planners in China have forgotten. Just as our own home grown ones fail to note our own past problems. The Humber Bridge never even paid back the cost of building it, let alone the interest upon it. Infrastructure doesn’t, necessarily, pay for itself. It is that upon which grand plans fail.

[…]

That it’s too expensive means that it’s not going to make money, not even meet its construction costs. And therefore it shouldn’t be built anyway, should it? Why spend more to build a railway than the benefit to be gained by having a railway? That’s just a waste of resources.

All of which is useful for our own infrastructure fetishists. It’s only if the new stuff is used that it can be worth building it. So, only build that which will be used, not whatever crosses those pretty little synapses of yours. Why, we might even insist that private economic actors put their own money at risk in order to concentrate minds on that very issue, of whether what is to be built will get used. Leave government planning out of it that is, in order to see what is worth building.

August 20, 2018

The Opium War

In Quillette, Jeffrey Chen reviews Song-Chuan Chen’s Merchants of War and Peace: British Knowledge of China in the Making of the Opium War:

The war had a name even before its first shot. The first recorded use of the moniker, the ‘Opium War,’ was in an 1839 piece in the London Morning Herald; within months it would be echoed across the benches of Parliament and across the carronades of the fleet sent to punish the Chinese crackdown on British trade.

The war’s nomenclature revealed from the beginning the multivalent views the British public held towards the war: it was at once the “unjust and iniquitous” Opium War — to use Gladstone’s well-known phrase — as well as the patriotic ‘China War,’ as its proponents wanted it to be called. The historiography of the war is similarly divided among varied lines. Some see the war as reflective of China’s failure to catch up to Western technologies; others emphasize the British desire to avenge their slighted national honour as the prime motive for the conflict. A wide array of scholars have placed a central focus on the role of opium, while some prefer to see the war in the context of imperial and economic expansion. Song-Chuan Chen’s Merchants of War and Peace: British Knowledge of China in the Making of the Opium War is a worthy addition to these voices.

Chen’s portrait of the Opium War places the role of British traders and their lobbying efforts in the foreground by arguing that it was British knowledge of China, as transmitted via the merchant class, that contributed to the ‘making’ (in the sense of both manufacture and execution) of the war. Chen asserts that it was the decade-long campaign of bellicose editorials and pamphlets on the part of the Canton merchant intelligentsia, as well as an accumulation of knowledge on the details of China’s coastal defences and overall military strength, that made it possible for Britain to both conceive of and win the war. The book casts, as its main actors, the ‘Warlike Party,’ a group of British merchants in Canton who lobbied for military intervention to expand the Canton System of trade, and the ‘Pacific Party,’ who opposed the war and criticised the diffusion of opium as an illicit and immoral drug. By narrowing his focus towards the production of knowledge, Chen also elevates the importance of language. A chapter of the book is devoted to a summary of the ‘Barbarian’ controversy – the disagreements and narratives spun around the British choice in translating the Chinese character 夷 (Yí) as ‘Barbarian,’ rather than ‘Foreigner.’

Chen’s account is thus of a battle as much between China and Britain as an internal conflict within the British public sphere. Though Chen is careful to nuance his depiction of the war by overlaying the many causal factors detailed by existing scholarship, his book makes two main arguments, which, in the words of the author, are new to the field: firstly, that the decisive factor in the war’s escalation was due to the machinations of the Warlike Party; and secondly, that the Canton System represented a ‘soft border’ through which the British were able to secure intelligence on the Qing state, without a reciprocal exchange of knowledge.

Written in engaging, lucid prose that presents its ideas clearly, if repetitively, Chen’s monograph is studded with riveting selections of his primary source research, drawn from the National Archives, UK, the First Historical Archives of China, the National Palace Museum, the British Library, SOAS Library, and Cambridge’s Jardine & Matheson archive. These quotations are often reproduced at generous length from the Warlike Party’s Canton Register and the Pacific Party’s Canton Press, and they provide a revealing account of the vigorous rhetorical strategies employed by the two camps.

July 27, 2018

“Tariffs are the classic example of government interventions with concentrated benefits and dispersed costs”

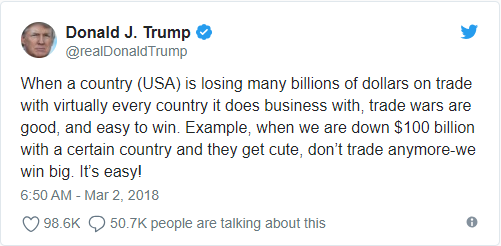

Robert Higgs on what he describes its supporters as “waging the trade war to end all trade wars”:

… even as Trump spouts venerable fallacies to justify and seek support for his destructive trade policies and related ad hoc actions, he and his supporters have sometimes offered a strange defense of their tactics: they purport to be seeking, at the end of the game, universal free trade, a world in which all countries have abandoned tariffs, quotas, subsidies, and other government intrusions in international exchange. In Wilsonian terms, they claim to be waging the trade war to end all trade wars. The idea is that by raising U.S. tariffs, they will induce other governments to lower and ultimately eliminate their own.

Of course, this rationale may be nothing more than wily claptrap, tossed out as a rhetorical bone to Republicans who favor freer trade. The administration’s actions to date certainly give no indication that it is aiming at global free trade. On the contrary. So the Wilsonian gambit may consist of nothing but hot air.

But if Trump and his trade advisers actually take this tactic seriously, they are deluding themselves.

First, and surely obviously, U.S. tariff increases will not induce other governments to lower their own, but to raise them, as the EU, China, Mexico, Canada, and other trading partners have already demonstrated. That’s why it’s called a trade war — because the “enemy” shoots back. History has shown repeatedly, most notably in the early 1930s, in the wake of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, that such trade wars only spiral downward, choking off more and more trade, despoiling the international division of labor in accordance with comparative advantage, and thereby diminishing real income in all the trading countries.

Second, the prospect of the U.S. government’s ever abandoning tariffs is slim to none. Tariffs are the classic example of government interventions with concentrated benefits and dispersed costs. This character makes them attract great support from protected special interests and little opposition from the general public — including other producers — when they are enacted or extended. They are easy for politicians to put in place and diabolically difficult for anyone to eliminate. Although the costs are great — much greater than the benefits for the economy as a whole — hardly anyone’s costs are great enough to justify mounting a potent political attack on the tariffs.

People who get tariffs put in place to protect them in the first place are well positioned to marshal strong opposition to any political attempt to eliminate these taxes on consumers who buy from competing, foreign suppliers. Consumers rarely know anything about why foreign goods are priced as they are, and producers, in general, are usually not affected enough by tariffs on imported raw materials and components to justify well-funded politicking against them.

July 9, 2018

1918 Flu Pandemic – Emergence – Extra History – #1

Extra Credits

Published on 7 Jul 2018Between 3 and 6 percent of the world’s population died in 18 months when the flu first tried to take over the world. In today’s episode we explore the flu outbreak’s origins from military camps across the United States and Canada.

The flu was the first modern plague — turning our interconnected world against us by spreading through shipping lanes, rail lines and the arteries of industrialized war. Yet it was also the first pandemic of the scientific age, where doctors could to some extent understand what was happening and stand against the infection, though they lacked the tools to stop it. Also, say hello to the voice of “professor” Matt!

June 13, 2018

May 22, 2018

The Fightinest Marine – Dan Daly I WHO DID WHAT IN WW1?

The Great War

Published on 21 May 2018Dan Daly was one of only two Marines to be awarded Medals of Honor in two separate conflicts. The first, for his actions in 1901 during the China relief. His second, for his actions during the U.S. invasion and occupation of Haiti in 1915. But he wasn’t done yet and after the U.S. entry into WW1 in April 1917, he was close to receiving his third one on the battlefield of Belleau Wood in France.

A variant factor in Chinese economic statistics

I’ve long been on the record as not trusting Chinese government statistics (some examples here, here here, here, here, here, here, here, here here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here), but this is a twist I hadn’t previously noticed:

A useful and basic rule of thumb about international economic statistics. Never, but just never, believe nor pay attention to anything about the Chinese economy for the first quarter of the year. No, this isn’t because our inscrutable bretheren dissemble more or less at this time of year, it’s not because their statisticians spend January drunk or hungover (unlike our own), it’s because the Chinese New Year obeys its own little calendar.

The modern Chinese New Year begins on the first new moon between January 21st and February 20th. Earlier calendar systems were more complicated:

Chinese five phases and four seasons calendar, used during the Zhou dynasty (c. 1046 BC-256 BC).

Image by Orienomesh-w, via Wikimedia Commons.

Well, OK, so if this was a western country that really celebrated the New Year (say, Scotland) then everyone would be back at work 48 hours later. However, the Chinese New Year is also the start of the two week holiday. Sorta a mixture between American Thanksgiving (you WILL eat at your mother’s table or a close simulacrum of it) plus a Wakes Week (English industrial towns would shut every single factory so that all could get away to the beach for a week. Well, beach not so much, Skegness maybe). The combination of the two means that near every factory in the country shuts for a couple of weeks as the largest migration in history takes place. All those migrant workers heading back to Mom’s dumplings.

If this all took place at the same time each year then our economic statistics would take account of it just fine with our seasonal adjustments. Just like we do with Christmas. We know very well that hundreds of thousands get hired for temporary jobs packing and delivering just before, get laid off immediately afterwards. We don’t see that reflected in the unemployment numbers because we’re not interested. We want to see trends, not known seasonal variations. So too with output and all that – many European factories do close in that week after Christmas. We don’t measure a drop in GDP then because we know about it therefore ignore it.

So Chinese official economic statistics are even less likely to correspond to reality during the first quarter than at any other time of the year.

Feature History – Opium Wars

Feature History

Published on 19 Oct 2016Welcome to Feature History, featuring the Opium Wars, western imperialism, and this fancy new intro and vignette.

The super sexy stuff like animation, voice, and script are all by the super sexy me.

The music is Anamalie and Clash Defiant, both by Kevin MacLeod

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Feature_History

May 14, 2018

China launches the second Type 001 aircraft carrier (Type 001A)

In the New York Times, Steven Lee Myers reports on the newest People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) aircraft carrier departing from Dalian to undergo its initial sea trials:

China launched its first domestically built aircraft carrier to begin sea trials on Sunday, reaching another milestone in the expansion of the country’s navy.

The aircraft carrier, as yet unnamed, left its berth at a shipyard in the northeastern port of Dalian after a blow of its horn and a display of fireworks, according to reports in state news media.

The Chinese Navy — officially the People’s Liberation Army Navy — already has one operational carrier, the Liaoning, which it bought unfinished from Ukraine after the collapse of the Soviet Union. That ship joined the Chinese fleet in 2012 and began its first operations four years later, putting China in the small group of seafaring powers that maintain aircraft carriers, led by the United States, which has 11.

The Liaoning, which appears to serve as a training vessel as much as a combat ship, was the centerpiece of a naval parade of 48 ships attended last month by China’s leader, Xi Jinping. The following week, it led a carrier battle group in live-fire exercises in the Taiwan Strait and in the East China Sea.

Since taking office, Mr. Xi has driven an ambitious effort to modernize the country’s military, reducing the traditional focus on readying the ground forces of the People’s Liberation Army to defend against an invasion of the mainland and increasing the emphasis on technology-dependent naval, air and missile forces.

The new carrier, built by the Dalian Shipbuilding Industry Company, has a similar design to the Liaoning but has been modified and expanded, according to Chinese and foreign experts.

May 7, 2018

DicKtionary – J is for Junk – Ching Shih

TimeGhost History

Published on 6 May 2018J is for Junk, boat of the Chinese,

For trade and for pleasure, they sailed the blue seas

Some junks were pirates, that ain’t a good thing,

And the queen of them all, was one Madame ChingJoin us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Written and Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Based on a concept by Astrid Deinhard and Indy Neidell

Directed by: Spartacus Olsson

Produced by: Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Edited by: Bastian BeißwengerA TimeGhost format produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH

The Chinese Civil War – Blood for Unity l HISTORY OF CHINA

IT’S HISTORY

Published on 5 Sep 2015After the fall of the Qing dynasty China fell apart and both, forces loyal to Chiang Kai-shek’s National Kuomintang Party and as Mao Zedong’s Communist Party of China, fought to rule the country. This bloody struggle would ultimately result in the Chinese Civil War. It would take more than 22 years but would come to a halt during the 2nd Sino-Japanese War. After Japan’s defeat, Mao’s troops grew strong quickly and soon after they were able to force Chiang Kai-shek and his followers out of China. They sought refuge in Taiwan. Shortly after, Mao Zedong called out the People’s Republic of China. Learn all about the Chinese Civil War in this episode of Battlefields with Indy Neidell.

April 13, 2018

India and the “Quad”

At Strategy Page, Austin Bay discusses India’s position, both geographically and militarily with respect to China:

As the Cold War faded, a cool aloofness continued to guide India’s defense and foreign policies. Indian military forces would occasionally exercise with Singaporean and Australian units — they’d been British colonies, too. Indian ultra-nationalists still rail about British colonialism, but the Aussies had fought shoulder to shoulder with Indians in North Africa, Italy, the Pacific and Southeast Asia, and suffered mistreatment by London toffs. Business deals with America and Japan? Sign the contracts. However, in defense agreements, New Delhi distanced itself from Washington and Tokyo.

The Nixon Administration’s decision to support Pakistan in the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War [Wikipedia link] embittered India. Other issues hampered the U.S.-India relationship. Indian left-wing parties insisted their country was a “Third World leader” and America was hegemonic, et cetera.

However, in the last 12 to 15 years, India’s assessments of its security threats have changed demonstrably, and China’s expanding power and demonstrated willingness to use that power to acquire influence and territory are by far the biggest factors affecting India’s shift.

In 2007, The Quad (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue), at the behest of Japan, held its first informal meeting. The Quad’s membership roll sends a diplomatic message: Japan, Australia, America and India. Japan pointed out all four nations regarded China as disruptive actor in the Indo-Pacific; they had common interests. Delhi downplayed the meeting, attempting to avoid the appearance of actively “countering China.”

No more. The Quad nations now conduct naval exercises and sometimes include a quint, Singapore.

The 2016 Hague Arbitration Court decision provided the clearest indication of Chinese strategic belligerence. In 2012, Beijing claimed 85 percent of the South China Sea’s 3.5 million square kilometers. The Philippines went to court. The Hague tribunal, relying on the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea treaty, supported the Filipino position that China had seized sea features and islets and stolen resources. Beijing ignored the verdict and still refuses to explain how its claims meet UNCLOS [Wikipedia link] requirements.

That is the maritime action. India and China also have mountain issues. In 1962, as the Cuban Missile Crisis diverted world attention, the two Asian giants fought the Indo-Chinese War [Wikipedia link] in the Himalayas. China won. The defeat still riles India.

April 11, 2018

Penn & Teller: Dalai Lama and Tibet

infinit888

Published on 13 May 2008Mainstream media seems to be only pushing the story about an oppressed Tibet and referring to the Dalai Lama as a saint.

This is a compilation of clips from Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! “Holier Than Thou” speaking about Tibet and the Dalai Lama.

April 9, 2018

Portrait of a protectionist

The latest of a long-running series by Don Boudreaux, all entitled “A Protectionist is Someone Who…”:

… if he is among the many protectionists (such as Donald Trump or Peter Navarro) who, finding meaning in bilateral trade accounts, detects danger for country A if country A has a trade deficit with country B, should also find danger for each private producer that has a trade deficit with another private producer. That is, if this protectionist were consistent in his views, the same reasoning that leads him to worry about America’s trade deficit with China should also lead him to worry about, say, The Trump Organization, Inc.’s trade deficit with each of its many suppliers, including with each of any janitors that The Trump Organization, Inc. has on its payroll or otherwise contracts to hire. (After all, I’m quite certain that no janitor hired by The Trump Organization, Inc., buys as much from The Trump Organization, Inc., and The Trump Organization, Inc., buys from any janitor.)

So why does the allegedly genius businessman who is now president of the United States – and whose many fans believe him to “tell it like it is” – not judge his own private company by the same standards that he so confidently insists are appropriate for judging Americans’ trade with non-Americans? After all, if China’s trade surplus with America really is evidence either of Chinese chicanery or of the incompetence of American leaders (or both), then it must also be true that a Trump Organization janitor’s trade surplus with The Trump Organization, Inc. is evidence either of that janitor’s chicanery or of the incompetence of Trump Organization leaders (or both).