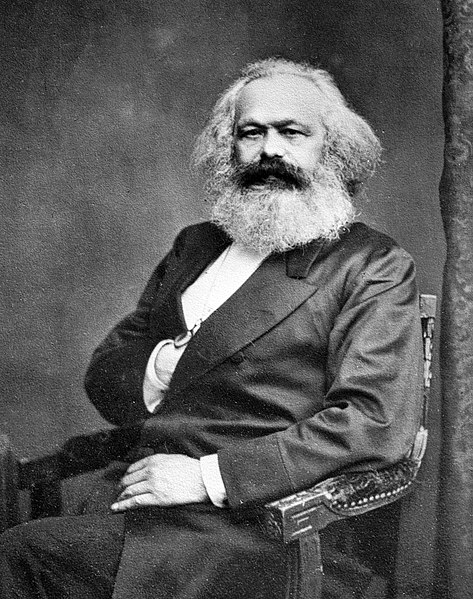

Lorenzo Warby on the malign influence of Karl Marx:

Despite — in some ways because of — all his Theorising about “capitalism”, Marx made no serious attempt to understand the actual dynamics of commerce, creating a (false) theory of economic parasitism (“surplus value”) that — both predictably, and in practice — motivated mass murder. If you convince a group of Homo sapiens that that group over there are economic parasites — and you and your society is better off without them — then you have primed them for mass murder. Hence, Marx’s theory was used to justify actual Marxist mass-murders, starting with Lenin’s infamous hanging order.

Marx’s economistic systematising created a pretence of being social scientist — to himself and even more to Engels — that many people have maintained ever since. Hence a pre-Darwinian metaphysician is even now regularly treated as if he was a social scientist. This despite being wrong about more or less everything — class, commerce, surplus, immiseration, the state, patterns of history, commodification, division of labour, foraging societies …

As I have noted elsewhere:

To have a state, farming niches have to be sustainable after taxes are extracted. That means resources are extracted before they turn into extra babies. This means that states create surplus (income above subsistence): indeed, they dominate the creation and extraction of surplus.

The perennial dominance of the state in extraction of surplus — and hence the creation of class structures — is nowhere more obvious than in Marxist states.

Philosopher Charles Taylor pointed out the tension between the claim to being science — and the causal determinism that goes with that — and the messianic vision that motivates Marx’s and Marxist activism. In any tension between the two, the latter wins because it is so powerfully motivating. This includes with Marx himself, which is why his “science” is so profoundly wrong in fact. It exists to justify the messianic vision.

No political (or religious) movement has killed and tyrannised more people than revolutionary Marxism. A Marxist is someone for whom no amount tyranny and mass murder will stop them worshipping the splendour in their head. This testifies to the power of the messianic vision.

Marx was the original launderer of ideas. Over decades of wrestling with the economics of Smith and Ricardo, he laundered — via economic reasoning — the metaphysical conclusions he reached in the 1840s to create a system that would “scientifically” generate and justify those conclusions. That those conclusions went mostly unpublished in his lifetime — with the most dramatic exception being The Communist Manifesto (1848) — does not belie this. Marx himself insisted on the centrality of this period of “self-clarification”.

Nothing he published later significantly contradicted those conclusions. Marx is the archetypal activist scholar, whose activism drives, and so degrades, his scholarship and analysis. He is the key formulator of the Dialectical Faith, that has generated various disastrous spin-offs, from his own economism to Lenin’s Jacobinising of Marxism to the Cultural Marxism of Lukacs and Gramsci, Critical Theory, and all forms of Critical Social Justice.

No form or derivative of the Dialectical Faith have ever generated a net positive contribution to human flourishing, or understanding, compared to available alternatives.

Ibn Khaldun was a far more acute analyst of the role of the state in the economy, and patterns within history, than Marx. Ibn Khaldun sought systematically to understand what he observed, participated in and read about. He was not laundering ideas, not justifying pre-set conclusions, nor judging evidence by his Theory.

Ibn Khaldun was a social scientist (arguably the first). Marx was not, he was pretending to be one (including to himself).

The Dialectical Faith holds that history is driven by dialectical process that transforms society from an oppressive past to a future liberated from constraints, if the oppressive elements of society are suppressed or abolished. As Marx tells us, our productive capacity will be so great, that we will so humanise the world, that division of labour will end for:

In communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.

Marx was not engaged in scientific enquiry but pseudo-scientific, or scientistic — the form of science without the substance — justification of already reached conclusions. He regularly judges and chooses evidence based on Theory, a pattern that has become endemic within all forms of Marxism and its spinoffs (such as Critical Theory). Marx exemplifies the activist principle that “what I can imagine — however self-contradictory — is so much better than what others have struggled to achieve”.

Marx’s picture of the evils of division of labour is metaphysical twaddle flatly contradicted by any serious study of the role of division of labour — and, for that matter, commodification — in production at scale. How can division of labour be such an alienating evil when it is built into sexual reproduction, into every eusocial species, even into the cells of every single complex organism?

The answer is via a ludicrous quasi-theological metaphysical inflation of human consciousness and creativity. Marx collectivises — through his notion of species-being — the Romantic notion of human fulfilment through self-expression.