In The Critic, Peter Caddick-Adams considers the revival of the biopic, with emphasis on Napoleon Bonaparte, thanks to the recent Ridley Scott movie:

Some of the first motion pictures were biopics, initially silent. In portraying a high-minded individual, historical or contemporary, who has influenced our lives in some way, cinema’s hope is that some of the character’s prestige will rub off into the film. Both sides of the Atlantic have seen countless examples, because the genre is traditionally presented as culturally above a thriller, western or a musical. Its offer is an invitation to see history. Let us take Oppenheimer or Napoleon, with Cillian Murphy and Joachim Phoenix in the title roles. Viewers are attracted by the concept of a true story, be it the designer of the first atomic bomb, or the little emperor who dominated Europe. They may know little or a lot about the subject, even if only hazy knowledge from distant schooldays, but they start with more base knowledge than any other genre.

Gifted directors, in this case Christopher Nolan and Ridley Scott, with their cast hold our hands and walk us into an historical context, hinting at grandeur or importance. We are led into a panorama of life that’s now seen as great or significant. Whether you’re glued to a small screen nightly, or whether you go to the cinema only once or twice a year, the biopic demands attention as “education”, in a way a thriller, horror or romcom flick does not. We are sold the idea that reel history (which can never be real history) somehow merits our valuable time, more than mere “entertainment”.

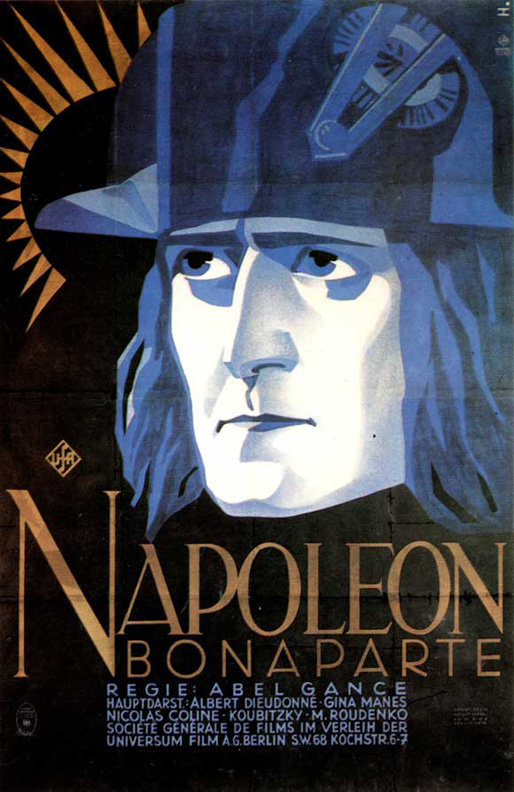

Napoleon first burst onto the screen in 1927 with a silent-era masterpiece directed by Abel Gance. Far ahead of its time, the final scenes were shot by three parallel cameras, designed to be projected simultaneously onto triple screens, arrayed in a horizontal row called a Triptych, the process labelled “Polyvision” by Gance. It widened the cinematic aspect to a field of vision unknown then or since. The director tried to film the whole in his Polyvision, but found it too technical and expensive. When released, only the centre screen of footage was shown, to a specially composed score. Designed as one episode of several to tell the emperor’s life, which we would today label a franchise, the 1927 extravaganza came in at 5.5 hours, necessitating three intermissions, including one for dinner. Gance had interpreted his biopic as a grand opera. It has been much trimmed and revisited by other directors, including Francis Ford Coppola in the 1980s, and restoration of lost footage is still ongoing. I saw the 5.5-hour version in the Royal Festival Hall in 2000, with a score by Carl Davies (of World at War fame). For a film emerging from the Stone Age of cinematography, its excitingly modern ambition was worth my bum ache. I could see what all the fuss was about.

Curiously, the real value of Gance’s Napoléon was in technique rather than content. If you think of the silent era, it’s mostly the comics who come to mind, playing out their dramas in front of a single static camera. Gance seized this new medium, first embraced in December 1895 by the Parisian Lumière Brothers, and turned it on its head. Napoléon featured not just the Triptych experiment, but many other innovative techniques commonplace today. These included fast cutting between scenes of alternating dialogue, extensive close-ups, a wide variety of hand-held camera shots, location shooting, multiple-camera setups and film tinting (colouring), so altering cinematography for ever.

Although Rod Steiger gave us a different take on Napoleon in Sergei Bondarchuk’s Waterloo of 1970, with its leading actors of the day and massive cast of extras, comprising much of a Soviet army division in period costume and filmed behind the old Iron Curtain, Ridley Scott’s new Napoleon is clearly paying homage to the Gance Napoléon in ambition and length. Scott pretty much picks up the story where Gance left off, and he is able to deploy technology of which Gance could only dream. However, with both films, screenwriter, director and actors are at a disadvantage common to all biopics of having to work against the viewers’ check-list of facts they know, or expect to see included. Thus Scott, like Gance, relies on spectacular technique over storyline. This brings viewers, especially my fellow fuming historians, into a collision between historical truth and the possibilities of celluloid story-making.

Most of us have a mental picture of the character we are invited to watch, which constrains actors and their make-up teams, who have to imitate particular people, with all the wigs, prosthetics and accents that entails. Yet, to view the biopic as a piece of history is to miss the point of the motion picture industry. Pick up a screenplay, and you will be surprised at how few pages it comprises, how few words on each page. None read like a literary biography. With only 90–120 minutes in a typical movie, there is not enough time to cover a character’s full life — not even that of Napoleon in 5.5 hours. Instead, the challenge for the writing-directing team is to extract snippets of a life to demonstrate the evolution of character.