I first encountered the idea of Ketman in an article by Severian on his old Rotten Chestnuts site (no longer online, alas). He was talking about it in the context of university:

I got into the higher ed biz fully intending to practice what Milosz calls “aesthetic ketman“. [“paying lip service to official ideology while secretly subverting it”] I loved my subject, but my subject was recondite enough, I figured, that I could keep the SJW bullshit to a bare minimum. I don’t remember what they called “intersectionality” back then, but whatever it was, I’d just make a few brief nods to it, then get on with my work in relative peace. Throw a few quotes from Foucault, Judith Butler, Gayatri Spivak, and the like in my dissertation intro, and that was that.

The problem, though, is that the sour pleasure of ketman is addictive, and like any addiction, you need to keep upping the dose to feel the same effect.

In The Critic, Colette Colfer discusses “gender ketman” today:

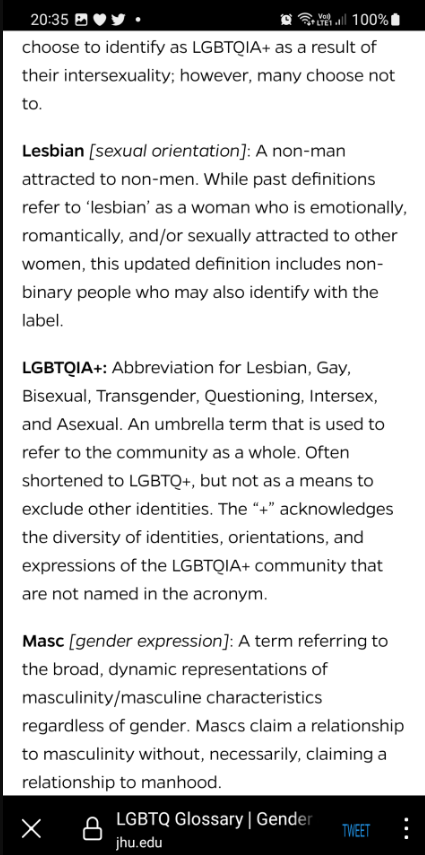

Ketman is a game of acting. It involves outwardly performing in compliance with a dominant belief system whilst inwardly rejecting it. Ketman is a form of self-protection, particularly when living under strict religious or totalitarian rule. Today, the game of Ketman is played as a way of hiding real opinions about gender ideology.

I first came across the concept of Ketman in Csezlaw Miłosz’s powerful 1953 book The Captive Mind, about life in Poland under Nazi right-wing and Stalinist left-wing totalitarian control. Miłosz dedicates one full chapter to Ketman. To play Ketman is to wear a mask, to simulate the behaviour that is required to fit in with the masses, to avoid the consequences of speaking up against a dominant ideology.

When the UK trade union for academics and lecturers, the University and College Union, released a video last month of their 2023 congress, it showed a crowded room of people loudly chanting in unison “trans rights are human rights”. They were holding up identical cerise-pink signs with words in all-caps, “TRANS RIGHTS ARE HUMAN RIGHTS”. I wondered, as I watched the clip, how many in that room were practising Ketman.

Miłosz came across the idea of Ketman in a book by Count Joseph-Arthur Gobineau (1816–82), entitled Religions and Philosophies in Central Asia. Gobineau served as a French diplomat in Persia during the mid-19th century, and he reckoned that the masses in Persia were practising Ketman. Gobineau also wrote about the “Allah lexicon” that included expressions such as inshallah and mashallah and insisted that scarcely one out of twenty Persians believed what they were saying.

Although Miłosz considered Gobineau a “rather dangerous writer”, he recognised Gobineau’s description of Ketman in the behaviour of people in Poland under Stalinist rule. The person practising Ketman must keep silent about their true convictions and must sometimes engage in trickery to deceive their adversaries. This can mean participating in rituals, waving banners, saying words or phrases to deceive others, and writing books filled with ideas the authors themselves don’t believe.

Miłosz said there were many different varieties of Ketman. Versions outlined in The Captive Mind include Metaphysical Ketman, which involved pretending to have no religious beliefs; and Ethical Ketman, which resulted from inwardly opposing the ethics of the “New Faith” of Stalinist communism, such as informing on neighbours.

However, practicing Ketman comes at a cost:

Miłosz points out that when a person plays Ketman for an extended period of time, they end up unable to distinguish their real self from the self they simulate. It’s almost like they begin to believe the lie. This level of association with the role being played gives some relief however, as the person no longer has to worry about dropping their guard when in conversation with others.

Severian, as you’d expect, has a more direct way of explaining it:

But more importantly, there’s the pleasure of ketman. So long as I make a few radical noises, I can get you sheep to believe anything I say. I used to tell people I studied transgendered potato farmers in the Kenyan uplands. I told this obnoxious girl from the Gender Studies department my dissertation was on resistance strategies of Eskimos in the Waffen-SS. I cited Alan Sokal’s hoax paper on the social construction of gravity in every seminar taught by a radical feminist, and no one ever called me on it. Anyone who thinks I’m kidding obviously hasn’t been on campus in the last 20 years or so. It was fucking hilarious …

… for a time. And then it got sad, then nauseating, because I eventually realized I was no different from the fools who swallowed my bullshit. It doesn’t matter if you’re being exquisitely ironic when you tell a room full of freshmen that “gender is a social construction”. They can’t recognize irony anyway, and even if they could, parroting the phrase “gender is a social construction” is still required to pass the class. More importantly, what if they did recognize it? I’m up there thinking I’m a shitlord, speaking truth to power to anyone smart enough to figure it out, but all they see is another fat, middle-aged sellout parroting nonsense. If I were serious about my shitlordery, they think, then I’d quit. But I don’t quit, which must mean my so-called “principles” are worth … what? We’ve already established you’re a whore, madam; now we’re just haggling over the price.