seangabb

Published 10 Feb 2021In 120 BC, Rome was a republic with touches of democracy. A century later, it was a divine right military dictatorship. Between January and March 2021, Sean Gabb explored this transformation with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

March 21, 2022

Republic to Empire: Sulla A Failed Reaction

For some reason, Canadians’ interest in alternative currencies has risen substantially since February

I’m far from alone in taking the Canadian government’s absurd over-reaction to the Freedom Convoy 2022 political protest in February as a reason to be concerned about the Canadian banking system. Until then I’d paid very little attention to alternative currency options like Bitcoin and the like, but I now understand that they may be a key element in future financial planning. At Quillette, Jonathan Kay explains that he realized at the same time he needed to know much more about crypto:

“Bitcoin – from WSJ” by MarkGregory007 is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

On February 15th, following weeks of anti-vaccine-mandate protests in downtown Ottawa, Justin Trudeau lurched from complete inaction to absurd overreaction by declaring a national emergency. One effect of this was that banks were suddenly authorized to freeze the personal assets of citizens linked with the protests, civil liberties be damned. Around the same time, moreover, hackers acquired and published identifying information associated with thousands of people who’d donated money to the protest movement. Rather than denounce this apparent criminal data breach, many public figures — including Gerald Butts, who’d been Trudeau’s right-hand man before resigning amid scandal in 2019 — actually celebrated this doxxing. Some media outlets even tried to mine the dox information for clickbait before being stung by a public backlash. While I hadn’t donated to the Freedom Convoy movement, I was sufficiently appalled by these developments that I started educating myself about how one might donate to a similar cause without government officials and social-media hyenas exploiting these transactions as a pretext to attack my assets and reputation.

The easiest way to get into the crypto market, I learned, is simply to open an account at an exchange platform such as Coinbase or Wealthsimple. But while they’re easy to use, exchange platforms also generally require clients to supply government-issued ID when they secure their accounts, and transactions are traceable by authorities. To assure myself of real anonymity and theft-protection, my tutor instructed me, a better (if more complex) option is “cold storage”. This is a real physical device — in my case, something called a Ledger — that acts as a personal crypto wallet.

My Ledger (which looks like a large USB key drive) contains the data required to generate the “private keys” (which look like long passwords, though that isn’t quite what they are) that allow me to send my crypto to other people. And that spending can be done only in those moments when the device is connected to the Internet, after which it can be relegated to a drawer or safe (thus the metaphorical concept of “cold storage”). On the other hand, I can receive money even if the Ledger is offline, so long as the sender has my public key, which (unlike a private key) is generally safe to give to others (such as, say, a prospective donor to any charitable cause that I might establish).

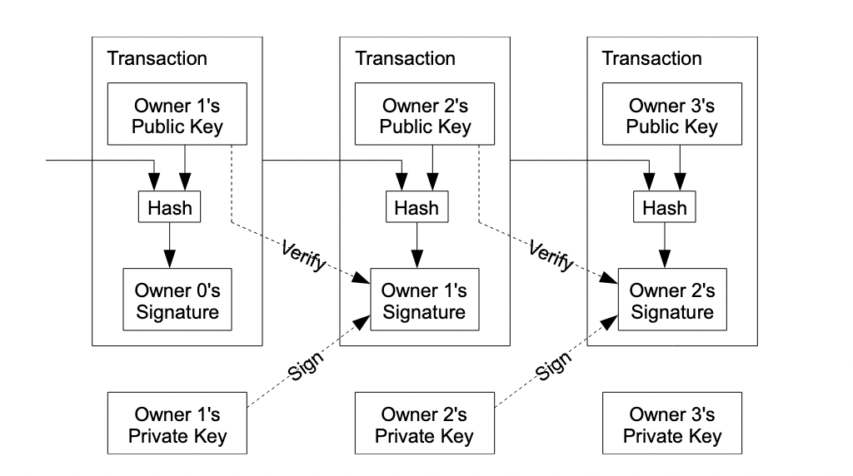

Bitcoin’s basic mechanics were set out in 2009 by the much-mythologized pseudonymous author (or collective) known as “Satoshi Nakamoto”. In a legendary white paper titled Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System, Satoshi describes the newly conceived electronic coin as consisting of a chain of digital signatures (a blockchain) that build one upon the next through a mathematical mechanism known as a cryptographic hash function — a one-way function whose output doesn’t expose the original private key to reverse-engineering. So once a bitcoin transaction is recorded and added in verified form to the blockchain by everyone — this being the “public distributed ledger” that bitcoin users are part of — the transaction can’t be erased or reversed (with one important theoretical exception, described later on).

Image contained in Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System, demonstrating the use of public and private keys to verify and sign bitcoin transactions.

Of course, you don’t need to understand how this cryptography works to use cryptocurrency. But it is worth getting your head around an important concept that fundamentally separates crypto from conventional assets such as, say, money that sits in a bank account. Your bank account number doesn’t have any value in and of itself: It’s just an institutional convenience that tells you and your bank where your actual money’s been filed (which is why that account number sits in plain sight on every physical check you sign, assuming you still use checks). But in the case of bitcoin, a private key basically is money — in the sense that anyone with access to such a key can spend the associated funds. And so if you lose your private-key information, or it gets stolen by a thief, there’s no 1-800 helpdesk number. It’s gone forever.

M44 Submachine Gun: Finland Copies the Soviet PPS-43

Forgotten Weapons

Published 17 Nov 2021http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

https://www.floatplane.com/channel/Fo…

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.forgottenweapons.com

The kp/31 Suomi submachine gun in Finnish service was an outstanding weapon, but it was slow and expensive to manufacture. When Finnish forces began capturing Soviet PPS-42 and PPS-43 submachine guns from the Soviets in the Continuation War, it was very quickly decided that Finland should copy the design. This was a far simpler, far cheaper stamped sheet-metal design that was not as refined as the Suomi, but much more efficient to make.

The Sudayev design was changed only minimally; primarily to fit the Finnish cartridge (9x19mm Parabellum) and magazines. The guns were originally designed to use the 50-round quad-stack boxes and 71/72 round drums of the Suomi, but also used the Swedish Carl Gustaf m/45 magazine that was adopted by Finland after WW2.

Two companies were approached to produce the M44; Tikkakoski and Ammus Oy. Ammus was unable to source raw materials for the project, and only Tikka put the guns into production. Marshal Mannerheim initially wanted 50,000, but the order was reduced to 20,000 — of which only 10,000 were actually made, due to limited material availability before the end of the war led to production ending. Another 400 were assembled from remaining parts after the war.

In the 1950s, a plan was begun to resume M44 production in order to completely replace the Suomi in Finnish inventory. However, this plan was interrupted when Sam Cummings of InterArms made a deal to trade Finland about 75,000 surplus Sten guns for Finland’s supply of 7.35mm Carcano rifle (received as aid from Italy during the war) along with a melange of old machine guns. This was a sufficient quantity of Stens to handle the duties of the Suomi, and so the Sten went into Finnish service and M44 production was never resumed.

Those Carcano rifles were in turn imported into the United States, and this is why the majority of 7.35mm Carcano here bear Finnish “SA” property stamps. The same is true for the significant number of Chauchat automatic rifles in the US with Finnish property marks, which were also part of the deal.

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

6281 N. Oracle 36270

Tucson, AZ 85740