The Great War

Published 15 Aug 2020Sign up for Curiosity Stream and get Nebula bundled in: https://curiositystream.com/thegreatwar

While the Greco-Turkish War was still raging, the last of the peace treaties between the Allies and the Central Powers was finalized in Paris. But the Turkish Nationalist Movement under Mustafa Kemal would not accept the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres – even though the Ottoman government had signed it.

» SUPPORT THE CHANNEL

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/thegreatwar» OUR PODCAST

https://realtimehistory.net/podcast – interviews with World War 1 historians and background info for the show.» BUY OUR SOURCES IN OUR AMAZON STORES

https://realtimehistory.net/amazon *

*Buying via this link supports The Great War (Affiliate-Link)» SOURCES

Halide Edib Adivar, The Turkish Ordeal: Being the Further Memoirs of Halidé Edib, (Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2012)John Darwin, Britain, Egypt and the Middle East, (London: Macmillan Press, 1981)

M.L. Dockrill and J. D. Goold, Peace Without Promise: Britain and the Peace Conferences, 1919-1923, (Connecticut: Hamden, 1981)

T G Fraser, Andrew Mango and Robert McNamara, The Makers of the Modern Middle East, (London: Gingko Library, 2015)

Phillip S Jowett, “Armies of the Greek-Turkish War: 1919-1922”, Men at Arms, no 501, (2015)

Michael Llewellyn Smith, Ionian Vision: Greece in Asia Minor 1919-1922, (London: Allen Lane, 1973)

Margaret Macmillan, Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World, (London: Macmillan, 2019)

A.E. Montgomery, “The Making of the Treaty of Sèvres of 10 August 1920”, The Historical Journal Vol. 15, No. 4 (December, 1972)

New York Times, “Turk Nationalists Capture Beicos” (July 6, 1920) https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/time…

George Riddell, Lord Riddell’s Intimate Diary of the Peace Conference and After: 1918-1923, (London: Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1933)

» MORE THE GREAT WAR

Website: https://realtimehistory.net

Instagram: https://instagram.com/the_great_war

Twitter: https://twitter.com/WW1_Series

Reddit: https://reddit.com/r/TheGreatWarChannel»CREDITS

Presented by: Jesse Alexander

Written by: Jesse Alexander

Director: Toni Steller & Florian Wittig

Director of Photography: Toni Steller

Sound: Toni Steller

Editing: Toni Steller

Motion Design: Philipp Appelt

Mixing, Mastering & Sound Design: http://above-zero.com

Maps: Daniel Kogosov (https://www.patreon.com/Zalezsky)

Research by: Jesse Alexander

Fact checking: Florian WittigChannel Design: Yves Thimian

Contains licensed material by getty images

All rights reserved – Real Time History GmbH 2020

August 16, 2020

Greco-Turkish War – Treaty of Sèvres I THE GREAT WAR 1920

Surviving the surrender of Japan as allied Prisoners of War

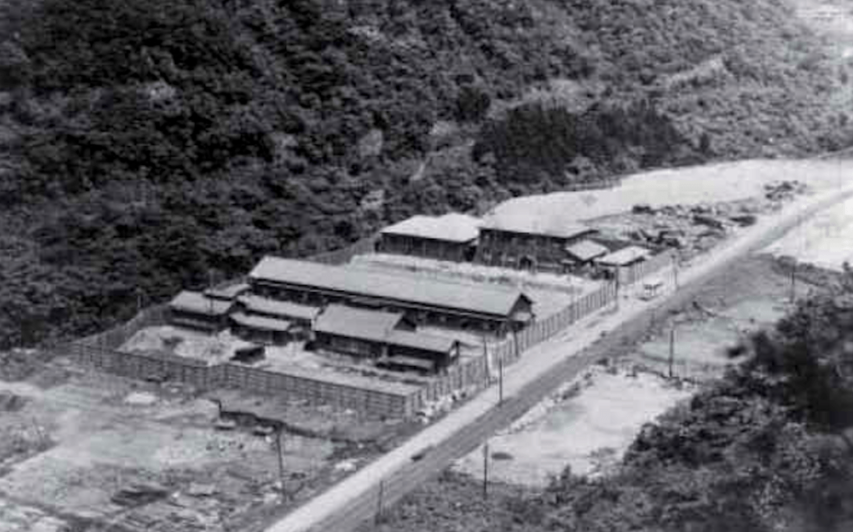

Seventy-five years ago, the war in the Pacific had ended with the surrender of Japanese imperial forces after the atomic bombing attacks at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The war may have technically ended, but there was still plenty of danger for the surviving POWs in various camps around the Japanese home islands. George MacDonnell was a Canadian soldier who had been captured in the fall of Hong Kong early in the Japanese swathe of conquest that engulfed so many areas. He had been held as a slave labourer at a prison camp in the mountains of northern Honshu in Iwate Prefecture. In Quillette, he tells how his captivity came to an end:

It was noon on August 15th, 1945. The Japanese Emperor had just announced to his people that his country had surrendered unconditionally to the Allied Powers.

To those of us being held at Ohashi Prison Camp in the mountains of northern Japan, where we’d been prisoners of war performing forced labour at a local iron mine, this meant freedom. But freedom didn’t necessarily equate to safety. The camp’s 395 POWs, about half of them Canadians, were still under the effective control of Japanese troops. And so we began negotiating with them about what would happen next.

Complicating the negotiations was the Japanese military code of Bushido, which required an officer to die fighting or commit suicide (seppuku) rather than accept defeat. We also knew that the camp commander — First Lieutenant Yoshida Zenkichi — had written orders to kill his prisoners “by any means at his disposal” if their rescue seemed imminent. We also knew that we could all easily be deposited in a local mine shaft and then buried under thousands of tons of rock for all eternity without a trace.

We had no way of notifying Allied military commanders (who still hadn’t landed in Japan) as to the location of the camp (about a hundred miles north of Sendai, in a mountainous area near Honshu’s eastern coast), whose existence was then unknown. Because of the devastating American bombing, Japan’s cities had been reduced to rubble, its institutions were in chaos, and millions of Japanese were themselves close to starvation, much like us. The camp itself had food supplies, such as they were, for just three days.

Lieut. Zenkichi seemed angry, and felt humiliated by the surrender. Yet he appeared willing to negotiate our status. And after some stressful hours, we reached an agreement: The Japanese guards would be dismissed from the camp, while a detachment of Kenpeitai (the much feared Military Police) would provide security for Zenkichi, who would confine himself to his office.

To our delight, the local Japanese farmers were friendly, and agreed to give us food in exchange for some of the items we’d managed to loot from the camp’s remaining inventory — though, unfortunately, not enough to feed the camp. Meanwhile, through a secret radio we’d been operating, we learned that the Americans were going to conduct an aerial grid search of Japan’s islands for prison camps. We followed the broadcasted instructions and immediately painted “P.O.W.” in eight-foot-high white letters on the roof of the biggest hut.

Two days later, with all of our food gone, we heard a murmur from the direction of the ocean. The sound turned into the throb of a single-engine airplane flying at about 3,000 feet altitude. Then, suddenly he was above us — a little blue fighter with the white stars of the US Navy painted on its wings and fuselage. But the engine noise began to fade as he went right past us. Please, God, I thought — let him see our camp.

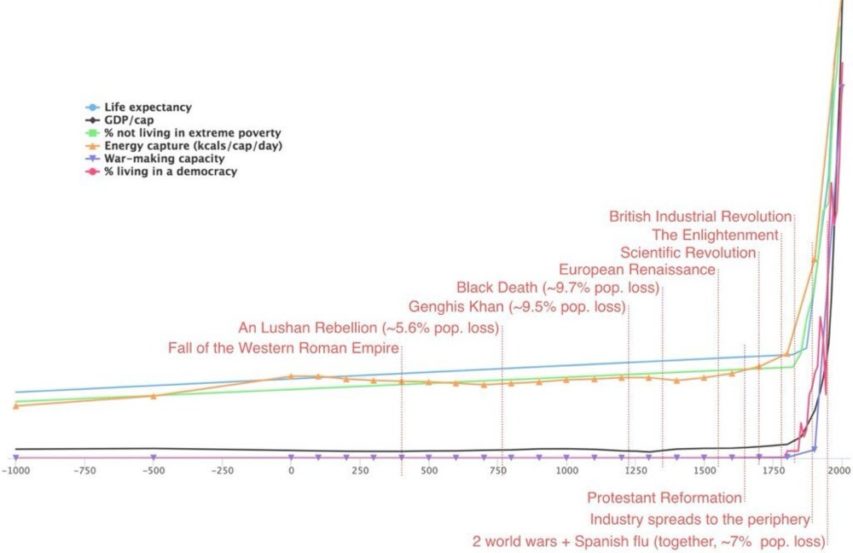

This is a “hockey stick” graph you can believe

Brian Micklethwait says this graph, unlike the more famous (debunked) “hockey stick”, shows one of the most important moments in human history:

If that graph, or another like it, is not entirely familiar to you, then it damn well should be. It pinpoints the moment when our own species started seriously looking after its own creature comforts. This was, you might say, the moment when most of us stopped being treated no better than farm animals, and we began turning ourselves into each others’ pets.

Patrick Crozier and I will be speaking about this amazing moment in the history of the human animal in our next recorded conversation. That will, if the conversation happens as we hope and the recording works as we hope, find its way to here.

I’m not usually one for podcasts, in the same way that I’m not an audiobook user: I find I’m unable to do other things while listening to the spoken word, and it’s always far faster to read a text than to have it read to you. In this particular case, I might try to make an exception, and give up hope of doing anything else productive while I listen.

Collier Flintlock Revolvers

Forgotten Weapons

Published 9 Nov 2016Sold for:

First Pattern Musket: $51,750

Second Pattern Rifle: $46,000

Second Pattern Pistol: $63,250Elisha Collier is probably the best-known name in flintlock revolvers — to the extent that any flintlock revolvers are well known. Because of the great cost and required skill to manufacture a functional repeating flintlock handgun without modern machine tools, these weapons were never common, but they were made by a number of gunsmiths across Europe. Collier and a fellow American gunsmith named Artemis Wheeler developed this particular type (the specific contributions of each party are not known), and Collier patented it in England in 1818. He proceeded to market the guns, which appear to have been made for him under contract by several high-end British gunsmiths (including Rigby and Nock).

Collier made three different basic types of guns. They share the main feature of a revolving cylinder which must be indexed manually between shots (seeing them while traveling in India was reportedly the inspiration for Samuel Colt’s idea to connect the mechanical functions of hammer and cylinder to invent the single action revolver). The first two patterns of Collier are flintlocks, differing in lock and cylinder design, as well as having slightly different mechanisms to self-prime. The third pattern was actually made as percussion guns, as Collier’s guns were being made right at the end of the flintlock period and the dawn of the percussion cap. In total, 350-400 guns were made, including 50-100 bought by the British military for use in India.

Cool Forgotten Weapons Merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

QotD: Labour is now the “party of government” even when they’re not in power

Labour, it seems to me and to many others I’m sure, has mutated from once upon a time being the party speaking for the poor, often against the government, to being the party of government, even when they aren’t the politicians in titular charge of that government. These people are now “supportive of the state”, to quote Hartley, even when they’re not personally in charge of it. It’s the process of government, whoever is doing it, whatever it is doing, that they now seem to worship. It is, as similar people in earlier times used to say, the principle of the thing, the principle being that they’re in charge. Many decades ago, Labour spoke for, well, Labour. The workers, the toiling masses. Now they represent most determinedly only those who labour away only in Civil Service offices or their allies in the media, in academia, and in the bureaucratised top end of big business.

Anyone official and highly educated sounding who challenges whatever happens to be the prevailing supposed wisdom of this governing class, on Coronavirus or on anything else, must be scolded into irrelevance and preferably silenced. The governors must be obeyed, even if they’re wrong. In fact especially if they’re wrong, just as the soldiers of the past were expected to obey their orders, no matter what they thought of the orders or of the aristocratic asses who often gave them. Whether they were good orders was an argument that those giving orders could have amongst themselves, but that orders must be obeyed was a given. “Capitalism” isn’t worth dying for, but this new dispensation is, right or wrong.

Our new class of entitled asses, together with all those who have placed their bets for life on carrying out their orders or trying to profit from them, seems now to be the limit of the Labour Party’s electoral ambition. And who knows? The awful thing is that this class and its hangers-on could be enough, in the not too distant future, to get them back into direct command of the governmental process that they so adore.

Brian Micklethwait, “Mick Hartley on the politics of the Lockdown”, Samizdata, 2020-05-15.