The Armchair Historian

Published 20 Jul 2018Check out EmperorTigerStar’s video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8j1sJ…

What Made The American Civil War So Deadly?

Sign up for The Armchair Historian website today:

https://www.thearmchairhistorian.com/Our Twitter: https://twitter.com/ArmchairHist

The Great Courses Plus is currently available to watch through a web browser to almost anyone in the world and optimized for the US, UK and Australian market. The Great Courses Plus is currently working to both optimize the product globally and accept credit card payments globally.

Sources:

Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era ~ James M. McPherson

The American War: A History of the Civil War Era ~ Gary W. Gallagher

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp…

https://blogs.ancestry.com/cm/12-stun…

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/ar…

January 7, 2020

What Made The American Civil War So Deadly? | Animated History

“HS2 will make the country worse off and should be stopped as soon as possible”

The British government recently reviewed the ever-escalating sums for the proposed HS2 high speed passenger rail connection that began at some £30 billion, then climbed to £50 billion, then £80 billion, and the latest estimate is up to £110 billion. Even by other countries’ high speed rail boondoggles, that is a breathtaking cost escalation. If, as it should, the government cancels the HS2 project, what happens to the money that was budgeted for the fiasco?

The figures used to justify HS2 were “fiddled” and that the project is most unlikely to deliver value for money — that’s the verdict of Lord Berkeley, the deputy chairman of the recent review into the project. He’s right of course and not solely because he’s repeating what I argued more than a year ago.

HS2 will make the country worse off and should be stopped as soon as possible. The government can mourn the money wasted and go off and do something else. Some suggest the HS2 money should be taken and spent on northern railways. Or as Lord Berkeley himself would prefer, on commuter lines in the Midlands.

But those offering these suggestions are making a very fundamental mistake: the real question is not which project most deserves this slab of funding, but whether the state should be spending this money at all.

This is not to say government should not be involved in funding any big infrastructure — everyone except the most hardcore anarchists accepts that state involvement in the economy is sometimes appropriate. But when it does intervene, it ought to be because there is an ironcast case for the betterment of the general population. That’s equally true whether we are talking about taxing to spend money now, or borrowing on the assumption that future benefits will pay back the debt incurred.

So, where does this leave the HS2 money? At some point it was decided that spending £30 billion, £50 billion, £80 billion or now as much as £110 billion on some nice choo-choos was an idea that justified taxing the public. Now it’s clear and obvious that it isn’t. Deciding afterwards that the government must spend all those billions on something else transport-related is missing the point entirely.

History Summarized: Alcibiades

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 11 Jan 2016The oracle at delphi simply tells him, “congratulations”. The standard of nudity was his idea. Narcissus gets shy around him. Patroclus was his boyfriend first. He is … the most interesting man in Ancient Greece.

Extra special thanks to Blue’s professor, Mr. Samons, who taught him about Greek history and the comedic potential of marshmallows and triremes.

Isaac Asimov at 100 … ish

It’s probably the centenary year for the late Isaac Asimov, but the date is only approximately correct:

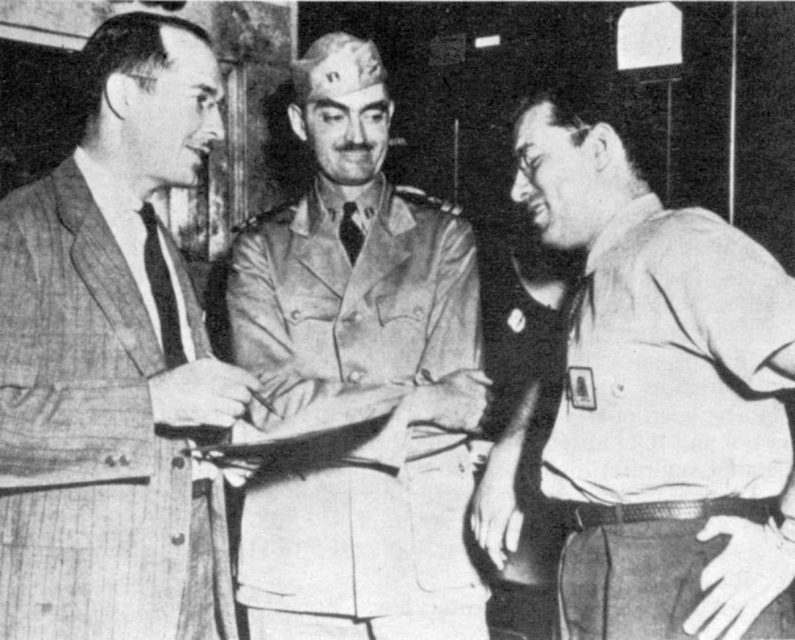

Robert Heinlein, L. Sprague de Camp and Isaac Asimov at the Philadelphia Navy Yard in 1944.

US government photo via Wikimedia Commons.

In actual fact the centenary is a bit of a fudge because Asimov never knew his actual birthday and picked January 2 as a likely date, and one that allowed for an extra holiday after the Christmas festivities. He was born around the turn of the year in 1920, three years after the Russian revolution, in the Soviet town of Petrovichi, although he emigrated to the US at the age of three.

Like many Russian Jews the family moved to Brooklyn in New York, and Asimov’s father ended up running a confectionery store and newsagent. Asimov taught himself to read at the age of five and taught his sister too, and consumed the pulp science fiction magazine stocked in his father’s shop.

At the age of 15 he applied to Columbia but was rejected, ostensibly on age grounds but, as he wrote in his autobiography I, Asimov, he recounted that the university had filled its quota of Jews for the year. After multiple rejections he eventually earned his Master of Arts degree in chemistry in 1941 and earned a Doctor of Philosophy degree in chemistry in 1948, serving as a civilian in the US Army in the Second World War.

An academic career beckoned and in 1949 he joined the Boston University School of Medicine as a biochemistry teacher. But by then he had already been getting science fiction short stories published for nearly ten years. In 1950 he wrote his first book and largely abandoned his teaching career, finding writing more lucrative and enjoyable.

[…]

Some thought Asimov had peaked as a science fiction writer by the mid 1960s, as he spent the next few years writing a lot of popular science books, non-fiction and school textbooks. He was even asked by Paul McCartney to write a science fiction musical for his then-band Wings, although the idea was eventually dropped.

But in the 1970s he came back into the SF fold with a series of books and short stories, winning two Hugo and two Nebula awards in the decade. He was also involved in some television and film work, having acted as a consultant on Star Trek in the 1960s.

In 1981 he was approached by a publisher to return to the Foundation series and add more to the canon. Foundation’s Edge was published the next year year, to wide acclaim. This was followed by Foundation and Earth in 1986, Prelude to Foundation in 1988, and finally Forward the Foundation, which was published in 1993, one year after Asimov’s death.

Wars of the Roses | 3 Minute History

Jabzy

Published 23 Jan 2015Of course there’s a lot I left out.

And when I say “Lancaster”, it sounds out of place because I had to just record over me continuously saying “Lancashire”.

QotD: The cult of Le Corbusier

What accounts for the survival of this cold current of architecture that has done so much to disenchant the urban world — the original modernism having been succeeded by different styles, but all of them just as lizard-eyed? According to Curl, the profession of architecture has become a cult. It is worth quoting him in extenso:

A dangerous cult may be defined as a kind of false religion, adoption of a system of belief based on mere assertions with no factual foundations, or as excessive, almost idolatrous, admiration for a person, persons, an idea, or even a fad. The adulation accorded to Le Corbusier, accorded almost the status of a deity in architectural circles, is just one example. It has certain characteristics which may be summarized as follows: it is destructive; it isolates its believers; it claims superior knowledge and morality; it demands subservience, conformity, and obedience; it is adept at brainwashing; it imposes its own assertions as dogma, and will not countenance any dissent; it is self-referential; and it invents its own arcane language, incomprehensible to outsiders.

Anyone who thinks this is an exaggeration has not read much Le Corbusier. (His writing is as bad as his architecture, and bears out precisely what Curl says.) Nor is it difficult to find in the architectural press examples of cultish writing that is impenetrable and arcane, devoid of denotation but with plenty of connotation. Here, for example, is Owen Hatherley, writing about an exhibition of Le Corbusier’s work at London’s Barbican Centre (itself a fine example of architectural barbarism). According to Hatherley, Le Corbusier was:

the architect who transformed buildings for communal life from mere filing cabinets into structures of raw, practically sexual physicality, then forced these bulging, anthropomorphic forms into rigid, disciplined grids. This might be the work of the “Swiss psychotic” at his fiercest, but the exhibition’s setting, the Barbican — with its bristly concrete columns and bullhorn profiles, its walkways and units — proves that even its derivatives can become places rich with perversity and intrigue, without a pissed-in lift [elevator] or a loitering youth in sight. … [T]hese collisions of collectivity and carnality have no obvious successors today.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Crimes in Concrete”, First Things, 2019-06.