Historia Civilis

Published 24 Apr 2015Patreon | http://patreon.com/HistoriaCivilis

Donate | http://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr?…

Merch | http://teespring.com/stores/historiac…

Twitter | http://twitter.com/HistoriaCivilis

Website | http://historiacivilis.comMusic is “The Life and Death of a Certain K. Zabriskie, Patriarch” by Chris Zabriskie. (http://chriszabriskie.com/)

January 3, 2020

The Battle of Alesia (52 B.C.E.)

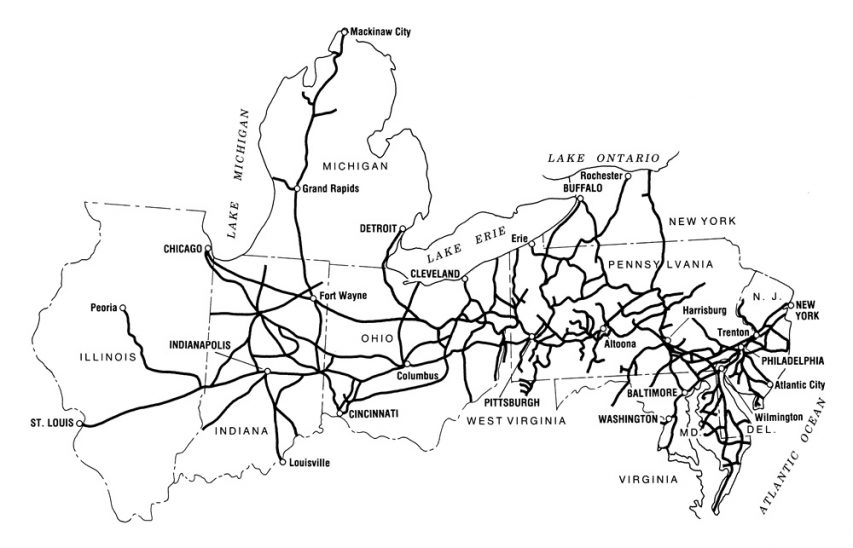

Fallen flag – the Pennsylvania Railroad

The origins and an outline history of the “Standard Railroad of the World” for Classic Trains magazine by George Drury:

The original Pennsylvania Railroad ran from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh. Much of its subsequent expansion was accomplished by leasing or purchasing other railroads.

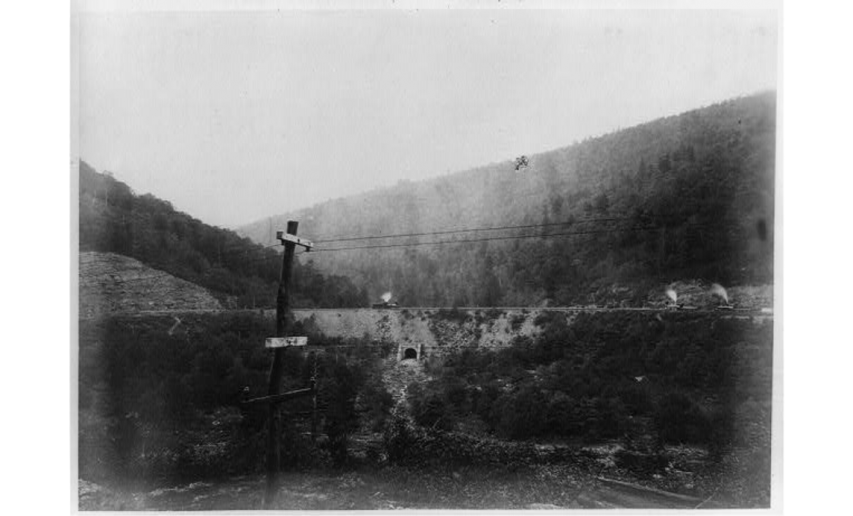

Construction began in 1847. Two years later the Pennsy made an operating contract with the Harrisburg, Portsmouth, Mountjoy & Lancaster, and by late 1852 rails ran from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh via a connection with the Portage Railroad between Hollidaysburg and Johnstown, Pa. The summit tunnel was opened in 1854, bypassing the inclined planes and creating a continuous railroad from Harrisburg to Pittsburgh.

In 1857 PRR bought the Main Line of Public Works and in 1861 leased the Harrisburg, Portsmouth, Mountjoy & Lancaster, putting the entire Philadelphia to Pittsburgh line under one management.

PRR also acquired interests in two major railroads, the Cumberland Valley and the Northern Central. The Cumberland Valley was opened in 1837 from Harrisburg to Chambersburg, and it was extended by another company in 1841 to Hagerstown, Maryland. The Baltimore & Susquehanna was incorporated in 1828 to build north from Baltimore. Progress was slowed because of the reluctance of Pennsylvania state officials to charter a railroad that would carry commerce to Baltimore. The line reached Harrisburg in 1851 and Sunbury in 1858. By then the railroad companies that formed the route had been consolidated as the Northern Central Railway. Pennsy acquired majority ownership of the Northern Central in 1900.

The Pennsy expanded into northwestern Pennsylvania by acquiring an interest in the Philadelphia & Erie Railroad in 1862 and assisting that road to complete its line from Sunbury to the city of Erie in 1864. The line to Erie was not particularly successful, but from Sunbury to Driftwood it could serve as part of a freight route with easy grades. The rest of that route was the Allegheny Valley Railroad, conceived as a feeder from Pittsburgh to the New York Central and Erie railroads. The Pennsylvania obtained control in 1868, and in 1874 opened a route with easy grades from Harrisburg to Pittsburgh via the valleys of the Susquehanna and Allegheny rivers. PRR leased the Allegheny Valley Railroad in 1900.

Horse shoe curve near Altoona on the Pennsylvania Railroad, circa 1874.

Photo by W.P. Mange & Co. via the Library of Congress.

But even the mighty can fall, and the PRR fell into difficult times after WW2:

During World War II Pennsy’s freight traffic doubled and passenger traffic quadrupled, much of it on the eastern portion of the system. The electrification was of inestimable value in keeping the traffic moving. After the war Pennsy had the same experiences as many other railroads but seemed slower to react. PRR was slower to dieselize, and when it did so it bought units from every manufacturer.

As freight and passenger traffic moved to the highways, Pennsy found itself with far more fixed plant than the traffic warranted or could support, and it was slow to take up excess trackage or replace double track with Centralized Traffic Control.

PRR was saddled with a heavy passenger business. It had extensive commuter services centered on New York, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh and lesser ones at Chicago, Washington, Baltimore, and Camden, New Jersey. It had gone through the Depression without going bankrupt.

Pennsylvania and New York Central surprised the railroad industry by announcing merger plans in 1957. The two had long been rivals, and the merger would be one of parallel roads rather than end-to-end. The merger took place on February 1, 1968 — and Penn Central fell apart faster than it went together.

“Union” – Battle of Monte Cassino – Sabaton History 048 [Official]

Sabaton History

Published 2 Jan 2020In early 1944, as the Allies are nearing Rome, Albert Kesselring orders a defensive line the likes of which rivals some of history’s greatest fortifications. Here, with the old hilltop abbey Monte Cassino looking down on the two front, the Axis and the Allies duel it out in a bloody and tiring fight for control of central Italy…

Support Sabaton History on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/sabatonhistory

Listen to The Art Of War (where Union is featured):

CD: http://bit.ly/TheArtOfWarStore

Spotify: http://bit.ly/TheArtOfWarSpotify

Apple Music: http://bit.ly/TheArtOfWarAppleMusic

iTunes: http://bit.ly/TheArtOfWariTunes

Amazon: http://bit.ly/TheArtOfWarAmz

Google Play: http://bit.ly/TheArtOfWarGooglePlayListen to Sabaton on Spotify: http://smarturl.it/SabatonSpotify

Official Sabaton Merchandise Shop: http://bit.ly/SabatonOfficialShopHosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Markus Linke and Indy Neidell

Directed by: Astrid Deinhard and Wieke Kapteijns

Produced by: Pär Sundström, Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Executive Producers: Pär Sundström, Joakim Broden, Tomas Sunmo, Indy Neidell, Astrid Deinhard, and Spartacus Olsson

Production Intern: Rune Væver Hartvig

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Edited by: Iryna Dulka

Sound Editing by: Marek Kaminski

Maps by: Eastory – https://www.youtube.com/c/eastoryArchive by: Reuters/Screenocean https://www.screenocean.com

Music by Sabaton.Sources:

– Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe

– National Portrait Gallery

– Bundesarchiv

– National Army Museum

– IWM E446, E 3020E, MH 1557, NA 12895, NA 15139, MH 6352, MH 11250, NA15141, C4363, HU 16546, NA 9807, NA 13274

– Soldiers of 100th Infantry Battalion during the Battle of Monte Cassino courtessy of Bco100bn from Wikimedia Commons

– Gebirgsjäger in position in Saltdal in 1940, Courtessy of Rudi Margreiter through Arkiv i Nordland

– Fondo Antiguo de la Biblioteca de la Universidad de SevillaAn OnLion Entertainment GmbH and Raging Beaver Publishing AB co-Production.

© Raging Beaver Publishing AB, 2019 – all rights reserved.

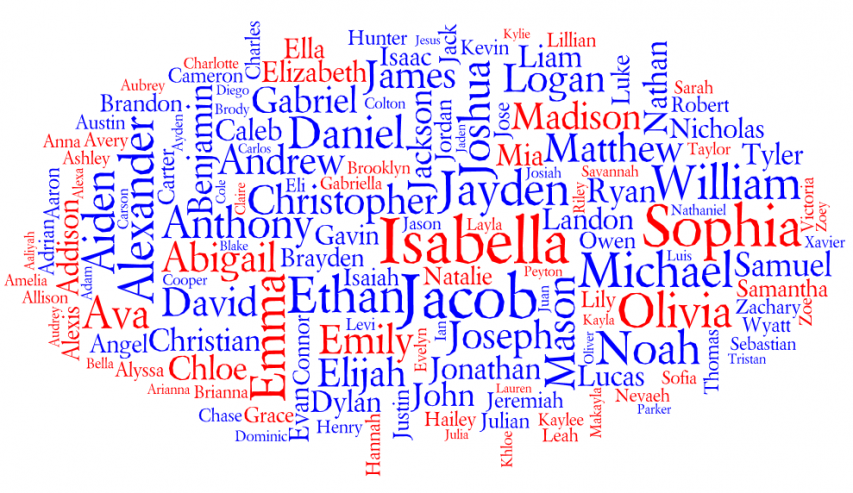

Magical thinking in names

Theodore Dalrymple relates the rather odd story of a young girl’s media-publicized objection to a math problem in school and then considers the girl’s given name in the larger context:

My attention was also caught by the first name of the politically-correct child: Rhythm. This is not a traditional name, though not actually ugly; but her parents have evidently accepted the increasing convention of giving a child an unconventional, and sometimes previously unheard of, name. This is a worldwide, or at least occident-wide, phenomenon. In Brazil, for example, parents in any year give their children one of 150,000 names, most of them completely new, made up like fake news, and in France, 55,000 children are born every year who are given names that are shared by three or fewer children born the same year. This latter is all the more startling because, until 1993, there was an old Napoleonic law (admittedly not rigidly enforced) that constrained parents to choose among 2000 names, mainly those of either saints or classical heroes.

What does the phenomenon of giving children previously unheard-of names signify — assuming that it signifies something? I think it is symptomatic of an egoistic individualism without true individuality, of self-expression without anything to express, which is perhaps one of the consequences of celebrity culture.

I performed an internet search on the words Rhythm as a given name. I soon found the website of a group called the Kabalarians, who believe that the name given to a child determines, or at least contributes greatly, to its path through life, especially in conjunction with the date of birth:

When language is used to attach a name to someone this creates the basis of mind, from which all thoughts and experiences flow. By representing the conscious forces combined in your name as a mathematical formula, one’s specific mental characteristics, strengths and weaknesses can be measured.

It invited readers to inquire about the psychological characteristics and problems of people with various given names. I invented a child called Rhythm of the same age, more or less, as Rhythm Pacheco. This was the result:

The name of Rhythm causes this child to be extremely idealistic and sensitive. She will find it difficult to overcome self-consciousness and to express her deeper thoughts and feelings in a free, natural way. She is too easily hurt and offended, and will often depreciate her own abilities. Because of her lack of confidence and her sensitivity, she will go to great lengths to avoid an issue. True affection, understanding, and love mean a great deal to her, as she is a romantic and emotional youngster. Often she will resort to a dream world when her feelings are hurt. She could be very easily influenced by others, for she will find it difficult to maintain her individuality. This problem could become more predominant during the teenage years. Although there is much that is refined and beautiful about her, the lack of emotional control could bring much unhappiness, repression, misunderstanding and loneliness later in life. Tension could also create fluid and respiratory problems. Because of the sensitivity created by this name, she will find it difficult to cope with the challenges of life.

There is, in fact, a semi-serious theory of nominative determinism, according to which a name may influence a person’s choice of career: two of the most prominent British neurologists of the first half of the twentieth century, for example, were Henry Head and Russell Brain. A recent Lord Chief Justice of England was called Igor Judge. And surely it must work in a negative direction too: no poet could be called Albert Postlethwaite. However rational one believes oneself, one might also experience a frisson of fear on consulting a doctor called Slaughter — as was called the doctor and popular novelist Frank G. Slaughter.

When I first went to Africa, I encountered patients whose first names were Clever, Sixpence or Mussolini. The first of these names was presumably an instance of magical thinking, while the second two were chosen merely because the naming parents liked the sound of them. Years later, during the civil war in Liberia, I met a constitutional lawyer called Hitler Coleman, who presumably desired to live his name down by concerning himself with the rule of law.

M20 75mm Recoilless Rifle: When the Bazooka Just Won’t Cut It

Forgotten Weapons

Published 8 Mar 2018Sold for $6,325.

Note that this is a rewelded action. It should be inspected by a professional before being fired (the firing footage in the video is a different example).

The M20 75mm Recoilless Rifle was developed starting in 1944 as a replacement for the 3.5″ bazooka in an antitank role. It was developed and produced in parallel with a 57mm recoilless rifle (the M18), and both entered service in March of 1945, seeing just a slight bit of combat use before the end of World War Two. It would be a mainstay of US troops in the Korean War, however, along with a 105mm recoilless rifle. The M20 fired HE, HEAT, and WP (smoke) rounds, with the projectiles weighing 20-22 pounds (about 10kg) and having muzzle velocities of about 1000 fps (305 m/s). The shaped charge HEAT warhead could penetrate about 4″ (100mm) of armor, and had an effective range of about 400 yards. The HE warhead could be effectively used out to about 1000 yards, and the gun was equipped with both direct fire and indirect fire optical sights in order to effectively use both types of ammunition.

By the Vietnam War, the M20 was on its way out, as were recoilless rifles in general — they were being replaced with wire-guided missiles for antitank use. However, the M20 remains in service today for avalanche control in many Western states — a neat repurposing of obsolete weaponry!

http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

If you enjoy Forgotten Weapons, check out its sister channel, InRangeTV! http://www.youtube.com/InRangeTVShow

QotD: Against The Grain

Someone on SSC Discord summarized James Scott’s Against The Grain as “basically 300 pages of calling wheat a fascist”. I have only two qualms with this description. First, the book is more like 250 pages; the rest is just endnotes. Second, “fascist” isn’t quite the right aspersion to use here.

Against The Grain should be read as a prequel to Scott’s most famous work, Seeing Like A State. SLaS argued that much of what we think of as “progress” towards a more orderly world – like Prussian scientific forestry, or planned cities with wide streets – didn’t make anyone better off or grow the economy. It was “progress” only from a state’s-eye perspective of wanting everything to be legible to top-down control and taxation. He particularly criticizes the High Modernists, Le Corbusier-style architects who replaced flourishing organic cities with grandiose but sterile rectangular grids.

Against the Grain extends the analysis from the 19th century all the way back to the dawn of civilization. If, as Samuel Johnson claimed, “The Devil was the first Whig”, Against the Grain argues that wheat was the first High Modernist.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Against The Grain“, Slate Star Codex, 2019-10-15.