In the latest installment of Anton Howes’ Age of Invention newsletter, he recounts the story of Bryan Donkin and his efforts to save innovators from excessive government interference:

One of the major arguments of the book I’m writing is that inventors’ talent for public relations and lobbying was one of the main reasons that Britain — rather unexpectedly — was the place that experienced an unprecedented acceleration of innovation.

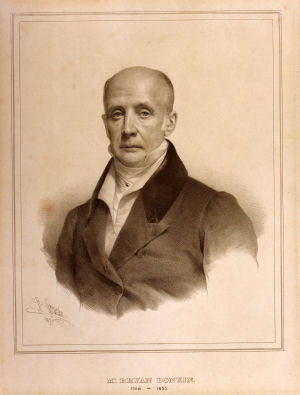

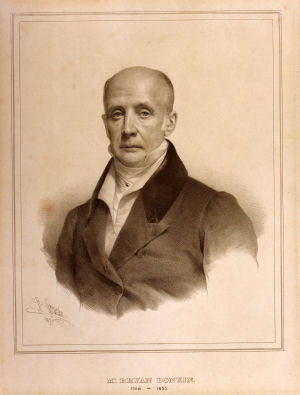

The greatest of these lobbyist-inventors has to be Bryan Donkin, a nineteenth-century mechanical engineer. As an inventor, Donkin improved threshing machines, dredging machinery, and a variety of other tools. He invented the steel pen, dabbled in chemistry, as well as phrenology, and was one of the key people responsible for mechanising the production of paper. He became best known for improving and commercialising tin cans for food. Mechanised paper-making and canned food, having both been invented in France, were perfected in Britain by Donkin. He was the archetypal tinkerer.

Bryan Donkin (1768-1855).

Photographer unknown via Wikimedia Commons.

But it’s as a lobbyist that I think Donkin was truly exceptional. His experience has important lessons for all would-be supporters of invention today.

In April 1817, Donkin read in his newspaper that there had been a disaster in Norwich: the boiler aboard the steamboat Telegraph had exploded. Of the boat’s twenty-two passengers, eight had died immediately in the blast, and another six had eventually succumbed to their wounds. It was a shocking tragedy. And for Donkin, doubly so: in addition to the human death toll, the explosion threatened to kill off one of the era’s newest and most exciting inventions.

Although some of the first trials of steamboats had taken place in the 1780s, it wasn’t until the turn of the century that they began to be practical. By 1817, the first commercially successful steamboat service in Britain, Henry Bell’s Comet, had been chugging its way up the River Clyde between Glasgow and Greenock for only five years. And Londoners like Donkin had only just seen their first steamboat, Margery, when she puffed her way into the Thames in 1815 (the following year, after becoming the first steamboat to cross the Channel, she reinvented herself in Paris as Elise). Thus, by the time of Telegraph‘s explosion, the passenger steamboat had only just been born. There was a very real risk that it would be banned.

Fortunately, however, the steamboat had Donkin in its corner. His immediate reaction upon reading about the explosion was to gather some of his engineer friends — Timothy Bramah and John Collinge — and set off for Norwich to view the explosion site for themselves. As the first expert engineers on the scene, they then took control of the narrative about the explosion. Donkin and his friends went straight to Norwich’s MP to ask him to set up a parliamentary select committee to look into the disaster. And while they waited for the politicians to be assembled for the committee, they held a series of public meetings about the disaster at the Crown & Anchor Tavern — a favourite haunt of London’s engineers. There, they had a chance to rally the rest of the profession and get their story straight about what must have caused the explosion.