Paul Sellers

Published on 5 Apr 2019The leg frame joinery is a very precise fit and things can go wrong if you are not experienced with how to deal with what we call glue freeze. One of Paul’s leg frames starts to stick but Paul explains throughout the glue up exactly how he deals with stubborn assemblies for a successful outcome. Paul deals with accurate alignment and cutting of the inner apron pieces including the wedges. His unique wedging method guarantees perfect alignment of the leg frames to the aprons while at the same time allowing the leg frames to be detached for moving, etc.

Episode 5 will be released on YouTube on the 19th of April but you can watch it right now at https://woodworkingmasterclasses.com/…

Want to learn more about woodworking? See https://woodworkingmasterclasses.com or https://commonwoodworking.com for step-by-step videos, guides and tutorials. You can also follow Paul’s latest ventures on his woodworking blog at https://paulsellers.com/

April 8, 2019

The Paul Sellers Plywood Workbench | Episode 4

Canada and the Battle of the Atlantic, part 7 by Alex Funk

Editor’s Note: This series was originally published by Alex Funk on the TimeGhostArmy forums (original URL – https://community.timeghost.tv/t/canada-and-the-battle-of-the-atlantic-part-3/1442).

Sources:

- Far Distant Ships, Joseph Schull, ISBN 10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

[Schull’s book was published in part because the funding for the official history team had been cut and they did not feel that the RCN’s contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic should have no official recognition. It is very much an artifact of its era, and needs to be read that way. A more balanced (and weighty) history didn’t appear until the publication of No Higher Purpose and A Blue Water Navy in 2002, parts 1 and 2 of the Official Operational History of the RCN in WW2, covering 1939-1943 and 1943-1945, respectively.]- North Atlantic Run: the Royal Canadian Navy and the battle for the convoys, Marc Milner, ISBN 10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Schull’s work, published 1985)

- Reader’s Digest: The Canadians At War: Volumes 1 & 2 ISBN 10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

- All photos used exist in the Public Domain and are from the National Archives of Canada, unless otherwise noted in the caption.

I have inserted occasional comments in [square brackets] and links to other sources that do not appear in the original posts. A few minor edits have also been made for clarity.

Earlier parts of this series:

Part 7 — The end of 1940, rise of the U-boat threat, the corvette waddles into the war, and expansion headaches at every turn

In North Atlantic Run, Marc Milner outlines some of the challenges being faced by the escort fleet in the changing conditions of the Battle of the Atlantic:

The fall and winter of 1940-1 was a peculiar time for escort operations, and pre-war concepts of trade defence and ASW were under strain. Losses to convoys were high, and authorities were baffled about effective countermeasures. There was a strong lobby within the RN, supported by Churchill while he was First Lord of the Admiralty and after he became prime minister, that favoured offensive action against U-boats by even the slenderest of escorts. The two schools of thought, one favouring an active pursuit of the enemy and the other the primacy of escort, were still matters for debate when the Canadians joined the Clyde Escort Force in late 1940. Through the winter the issue was finally resolved in favour of defence as the first priority. However, in light of the subsequent Canadian tendency to pursue even the most tenuous contacts with zeal, it is questionable if this exposure to nascent British escort tactics did the RCN much good. … By January all the River-class ships and four of the Towns — two having been held back by defects — were operating from the Clyde. During this second winter of the war there were also Canadian corvettes in the Clyde Escort Force participating in the crucial battles of the first phase of U-boat pack attacks. These corvettes were actually the ten of their class built in Canada to British accounts. All were completed before the freeze-up of late 1940, and the RCN assumed responsibility for their acceptance from the builders, commissioning into the RN, and manning for passage to the UK. Once in England the ships were to be handed over to the Admiralty. Unfortunately things did not go as planned, and the RCN ended up taking all ten of these corvettes into Canadian service.

The story of the “British” corvettes and their transfer to the RCN is an important one, for it illustrates the kinds of problems the RCN had when dealing with the RN. Because the ships were manned for passage only, their crews were the barest minimum, roughly assembled from spare hands, all of whom were designated for other duties upon completion of the crossing. Personnel from the first corvettes to go, for example, were assigned to HMCS Dominion, the RCN’s depot in Britain [Dominion was designated as a ship for administrative purposes, there was no actual physical vessel]. They were to form a manning pool for the destroyers already on operations in British waters. Those from the later passages were to return immediately to commission new RCN corvettes. All ten “British” corvettes were in the UK by early 1941 (the ships were named after flowers, following the Admiralty practice: Arrowhead, Bittersweet, Eyebright, Fennel, Hepatica, Mayflower, Snowberry, Spikenard, Trillium, and Windflower), but from the outset it proved impossible to obtain the release of their crews. As early as October of 1940, Dominion requested, on behalf of the Admiralty, that the crews of three recently arrived corvettes be allowed to remain aboard until the end of November. Reliefs for destroyer personnel, it was explained, could be drawn from the smaller ships (in the form of a “floating” pool) and the ships turned over to the RN in piecemeal fashion. NSHQ concurred, but no British replacement crews were forthcoming, and the issue remained unresolved. The corvettes, meanwhile, began escort operations with the Clyde force.

By February 1941 the delay in the release of men from the British corvettes began to affect planning of the RCN’s own expansion. Commodore G.C. Jones, RCN, commanding officer, Atlantic Coast (COAC) complained that the men should be returned to Canada before the opening of navigation on the St Lawrence River deluged the navy with new ships. “If our present commitments are to be met,” Jones observed, “it is essential this personnel be available.” He was advised by NSHQ that the matter was under review and that a decision was pending. Yet the issue lingered. In April the Admiralty petitioned the RCN to allow Canadian crews to remain aboard “so as to avoid impairing their efficiency by having to recommision them”. Since the ships were now operational, concern for their efficiency was justifiable. That escorts manned by skeleton crews and lacking many essential stores should have been committed to operations says a great deal about the tremendous need for escorts of any kind. It also suggests that communications between the RCN and RN were not what they should have been.

The misunderstanding over the nature of the RCN’s commitment to the ten British corvettes was to have long and serious repercussions. For the moment, the Admiralty’s concern for the efficiency of escorts operating in the embattled Western Approaches took precedence over all else. The Canadians were advised not to worry about the effect that losing these men would have on the buildup of the RCN’s own forces in the Western Atlantic. “It is considered,” the Admiralty’s signal went on to read, “that present circumstances justify some delay in these becoming effective.” Faced with the inevitable, the RCN acquiesced, so long as the ten corvettes were commissioned HMC ships. The Admiralty agreed and undertook to cover the costs and arrangements for refits, maintenance, and alterations and additions to equipment. The RCN was to look after running costs, pay, victuals, and the like (a similar arrangement existed with other Allied navies that undertook to man British warships fully themselves).

HMCS Arrowhead, one of the ten “British” corvettes built in Canada for the Royal Navy. Photo taken much later in the war, probably 1944-45.

Canada. Department of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / ecopy

Speaking of the corvettes themselves, the little vessels were 205 feet in length, 33 feet in beam, with a draught of 11.5 feet, a top speed of sixteen knots and a planned armament of one four-inch deck gun, a stock of depth charges, and a lone QF 2-Pounder Pom-Pom gun mounted on the “bandstand” above the engine room, with a planned crew of 80-90 men.

[Editor’s Note: The original design called for a crew about half this size, which translated into terribly overcrowded conditions aboard mid- to late-war corvettes. Adding new weapons, new communications and detection equipment, and miscellaneous additional gear, plus the added food and water for the larger crew meant these little ships were packed as densely as possible.]

Out of necessity, the ships’ armament would grow and change over the years. Many of the original RCN corvettes were also fitted with minesweeping gear. Shortages meant that many would forego the 2-Pounder Pom-Pom, instead receiving two Lewis guns (what these were supposed to do in the event of modern air attack was unknown.) [All allied navies were under-prepared for the risks of air attack early in the war, and it would take time — and significant losses — for that painful lesson to be learned.] Thankfully, most of them would never get within range of Luftwaffe bombers. The few of their own corvettes that the RN assigned to the Mediterranean all received significant anti-aircraft armament augmentation. The use of triple-expansion machinery instead of steam turbines meant the largely reserve/ex-merchant crewmen had an easier time working below. Underwater detection capability was provided by a fixed ASDIC dome; later modified to be retractable. Subsequent technological developments; like the High Frequency Radio Detection Finder or “Huff-Duff” would be added along with a number of different radar systems. More men would be added to crew these systems, putting additional demand on a ship where space was already at a premium.

The Flowers could be serviced by practically any small dockyard or naval station so many ships came to have a variety of different weapons systems and design modifications depending upon when and where they were refitted; there was really no such thing as a “standard” Flower-class corvette. The major changes could include:

- Original twin mast configuration changed to a single mast in front of the bridge, which was then often moved behind the bridge for improved visibility for bridge crew.

- Minesweeping gear removed to improve the ship’s range.

- Galley relocated from the stern to midships.

- Extra depth charge stowage racks added to the stern. Later even more storage was added along the walkways.

- Hedgehog anti-submarine weapons system fitted near the main gun platform.

- Surface radar fitted [in various marks, including some early, relatively primitive Canadian sets or more sophisticated British equipment].

- Forecastle lengthened to midships to provide more accommodation and better seaworthiness. Several vessels received a “3/4 length extension”.

- Increased flare at the bow. This and the forecastle lengthening would become standard features on later ships.

- Various changes to the bridge, typically lowering and lengthening it. Original enclosed compass house removed.

- Extra Lewis guns mounted on the bridge or engine room roof.

- Oerlikon 20-mm cannons fitted, usually two on the bridge wings, but sometimes as many as six spread out across the ship.

Any particular ship could have could have any mix of these, as well as other specialist one-off modifications.

A major difference between the RN vessels and the RCN, later USN, and other navies’ vessels was the provision of upgraded ASDIC and radar. The RN was a world leader in developing these technologies, and thus RN corvettes were often better-equipped for remote detection of enemy submarines than Canadian corvettes. A good example of this is the difficulty that RCN corvettes would have in intercepting U-boats with their Canadian-designed SW1C metric radar, while the RN vessels were equipped with the technologically advanced Type 271 centimetric sets. In addition, RCN corvettes were not initially equipped with gyrocompasses making ASDIC attacks more difficult.

The corvettes would never be handsome or comfortable ships. They would, as some cracked, “roll even on wet grass”. The captains who took them over were mostly ex-merchant officers, and while they were unpleasant commands, many developed a grudging respect for them. On the slipways of the Canadian coasts and the Great Lakes, the rest of the corvette fleet construction program was continuing on schedule.

Royal Navy Flower-class corvette HMS Picotee, pennant K63, shortly after being commissioned before modification, showing a number of original design features, including a much shorter bow and forecastle and a mast in front of the bridge, although the second mast has been removed.

Imperial War Museum photo by Lt. H.W. Tomlin, Royal Navy official photographer, via Wikimedia Commons.

Royal Navy Flower-class corvette HMS Jonquil later in the war showing the changes to the bow and forecastle.

Imperial War Museum photograph FL 22394, via Wikimedia Commons.

Terrence Robertson described for Maclean’s the first time he saw a RCN corvette at sea:

She was Canadian-built, Canadian-manned and named Windflower (incidentally one of the ten built for British use, then “returned” to the RCN). When the destroyer on which I was serving met this newcomer to the Atlantic battlefield in January 1941, we not unnaturally approached for a closer look. We saw on her foredeck a four-inch gun with a wooden barrel that drooped. Then we were warned to keep clear of her stern with the immortal signal: “If you touch me there, I’ll scream.”

HMCS Mayflower in 1942, one of the first ten corvettes built in Canada like her sister Windflower.

Photo from the Canadian Navy Heritage website, Image Negative Number MC-2589, via Wikimedia Commons.

Marc Milner continues:

The ten British corvettes were the second group of ships thrust upon a reluctant RCN by the British in less than a year. By RN standards the manpower requirements for the sixteen ships was not very large (about 1200 all ranks), but their acquisition represented a major expansion for the RCN. The means whereby the corvettes came into Canadian service also illustrates what was for the RCN a recurrent problem, that of obtaining the release of both men and ships lent to the RN. The first incident may well have been an absent-minded assumption on the part of many British officers that the RCN was committed to some form of Commonwealth navy. … In the event, the RCN put up an honourable fight, better than any of its later attempts. But once committed to the common cause, it had little choice but to turn in the direction where the powers that be deemed its efforts would achieve the most good. Perhaps more serious, with respect to the pending struggle for efficiency in the RCN’s own corvette fleet, was the Admiralty’s insistence that the Canadian navy could accept a delay in developing that efficiency. Ironically, a few short weeks later the British urgently requested that RCN corvettes be committed to convoy operations in the Northwest Atlantic. If Canada’s naval expansion seemed to lack direction, it is small wonder.

Provision of officers and men for the navy’s new ships was of course a primary concern as 1940 drew to a close. Much of the RCN’s disposable manpower went into commissioning the six Town class destroyers and ten corvettes taken over from the Admiralty — sixteen warships for which the navy had made no provision mere months before. Naturally this meant that the planning and assignment of personnel for the first wave of RCN corvettes was set back. Further, with virtually the whole fleet on active duty on the other side of the Atlantic, the navy had no ongoing access either to experienced personnel or to berths on operational warships which could serve as training posts for new officers and key non-substantive ratings. With proper management (by no means guaranteed), a modest interchange of new drafts and experienced personnel would have permitted a more orderly expansion of the fleet and shore establishments and would have softened the devastating impact of expansion in 1941. The navy considered this problem, and the Staff discussed the possibility of routing the occasional destroyer to a Canadian port where personnel could be exchanged. But the Naval Staff concluded that “it would be a most unwise policy to relieve any large percentage of a ship’s company when that vessel was acting in a War Zone.”

The first RCN corvettes to become operational therefore were commissioned with scratch crews. Although the navy kept its sound policy of not tampering with escorts in a war zone, the conditions which obtained over the winter of 1940-1 changed by the following spring. By then the fleet was operational closer to home and, technically at least, no longer in a war zone.

In late 1940 the RCN was faced with building up manpower needed to commission fifty-four corvettes, twenty-five minesweepers, and small numbers of motor launches — about seven thousand officers and men.

Windflower and Mayflower were the first two Canadian-built corvettes to make the passage to England. The navy was short of suitable weapons, so both had been fitted with dummy guns. The irrepressible pair were the first two of an eventual one hundred and twenty-two corvettes which, in the next four years, would carry thousands of pre-war farmers, miners, students, and white-collar workers into battle against the U-boat fleet. Their exploits were rarely spectacular, almost never heroic. But in the Battle of the Atlantic, the words “Canadian” and “corvette” became almost synonymous and the little ships created legends of courage and endurance.

They were needed more and more with each passing month. During the last week of February 1941, 150,000 tons of Allied merchant shipping was sunk; in the first two weeks of March, 245,000 tons; and this rate of loss continued into April and May. Three or four ships and their cargoes were being sunk daily.

Comparing the economic performance of China’s private versus state-owned companies

If you’ve been following the blog for a while, you’ll know that I’ve long been skeptical of any official economic statistics coming out of China. The reasons for my skepticism are that vast areas of the Chinese economy were owned or controlled by the state and reporting from those entities was performed through layers of officials whose positions and personal well-being depended on those reports being as positive as possible. In a capitalist system, announcing false production or profit figures will eventually be detected (sometimes not as soon as we’d like), and the company loses the trust of customers, suppliers, and banks, making survival much more difficult. In a state-owned organization, everyone in the hierarchy has a vested interest in false information not being uncovered or reported. In a private firm, you could lose your job … in a state-run enterprise, you could be shot or sent to a “re-education camp” along with all your family. The incentive to lie is much stronger when your risks are that high.

Tim Worstall comments on a recent report that compares the performance over time of Chinese private companies, privatized state companies, and companies that are still state-run:

That China has relaxed the governmental grip upon industry in recent decades is true. That China has become very much richer in recent decades is also true. The two are not a coincidence, there’s causality there. However, we hear often enough that it’s the residual control over industry by the government that drives that success. Sure, OK, so the bureaucracy doesn’t specify prices or detailed actions but the general guidance provided by a politically driven bureaucracy explains the outperformance.

Except it doesn’t. Those former state industries still enjoying that government guidance perform worse than the free market firms sadly lacking it. State planning is keeping China poorer than it need be, not aiding its growth.

The report he’s commenting on:

Changing the tiger’s stripes: Reform of Chinese state-owned enterprises in the penumbra of the state

Ann Harrison, Marshall W. Meyer, Will Wang, Linda Zhao, Minyuan Zhao 07 April 2019The conventional wisdom that privatisation of state-owned enterprises reduces their dependence on the state and yields positive economic benefits has not always been borne out by empirical work. Using a comprehensive dataset from China, this column shows that privatised SOEs continue to benefit from government support in the form of low-interest loans and subsidies relative to private enterprises that have never been state-owned. Although there are clear improvements in performance post-privatisation, privatised SOEs continue to significantly under-perform compared to private firms.

Much of China’s economic growth has been driven by the emergence of a vibrant private sector, today accounting for approximately 60% of GDP and 80% of employment. Conventional wisdom holds that privatisation of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) reduces their dependence on the state and yields positive economic benefits including enhanced firm performance, productivity, and innovation. The pro-privatisation argument is that the state either cannot monitor managers properly or chooses not to pursue efficiency because state interests take precedence over financial results (Boardman and Vining 1989, Vickers and Yarrow 1991, Shleifer and Vishny 1994). Empirical work, however, has produced mixed results on privatisation. For example, DeWenter and Malatesta (2001) found that, among the 500 largest firms globally in 1975, 1985, and 1995, private enterprises had significantly lower costs and higher profits than SOEs. Yet, when they examined a sub-sample of privatised firms, they found inconsistent results – performance increased post-privatisation, while leverage and employment increased mainly pre-privatisation. Market returns from privatisation also differed across countries, positive in Hungary, Poland, and the UK but insignificant elsewhere.

Our research on privatisation in China (Harrison et al. 2019) is unique in several respects. We analyse an extremely large sample of industrial firms, more than 3.5 million firm-years from 1998 to 2013, drawing on the Annual Industrial Survey conducted by the China National Bureau of Statistics. We compare privatised firms with firms that remained state-owned and firms that had never been state-owned. Most importantly, we compare both the performance and dependence on the state of privatised firms with firms having no prior state ownership. Overall, our results indicate selective performance gains from privatisation – privatised firms have greater productivity and are more likely to file patents than firms remaining state-owned even though their return on assets barely improves. The performance effects notwithstanding, privatised firms remain dependent on the state. Subsidies, concessionary interest rates, and loans granted to privatised firms remain at nearly the same levels as those to SOEs. Privatisation changes the behaviour of firms but not firms’ dependence on the state.

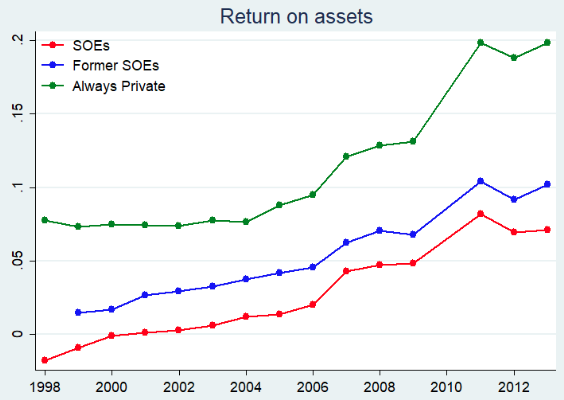

A graphical portrayal of the differing performance of the three types of Chinese companies from the report:

Why Don’t Trains Have Cabooses Anymore?

Today I Found Out

Published on 7 Sep 2016Never run out of things to say at the water cooler with TodayIFoundOut! Brand new videos 7 days a week!

In this video:

Carrying a brakeman and a flagman back when brakes were set by hand, when it was time to slow the train, the engineer would blow the whistle. This signaled to the brakemen, and one would emerge from the caboose and work his way toward the engine, while another would leave the engine and work his way back toward the caboose. At each car, the brakemen would stop and turn its brakewheel with a club. Once the train stopped, the flagman would leave the caboose with a flag, lantern or other visual display and walk back down the track to warn any approaching trains.

Want the text version?: http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.p…

QotD: Why does US healthcare cost so much?

This is a hotly debated question in health care policy. Here’s my rough stab at it: the 1970s inflation interacted particularly badly with two pre-existing policy choices: the tax deduction for employer-sponsored health insurance, and Medicare.

Start with employer-sponsored health insurance, which is, as everyone knows, tax advantaged relative to salary, because your employer can deduct it as an expense, but you don’t have to show it as income on your taxes.

This was an incredibly dumb decision, but in the defense of the folks who made it in the 1940s, at the time, health insurance wasn’t very expensive, because the health care system couldn’t do all that much (and the female labor that ran hospitals was cheap due to discrimination, or in the case of nuns, basically free).

Come the 1970s, inflation started causing a problem called “bracket creep”. Back then tax brackets weren’t indexed for inflation, so as inflation went up, folks got pushed into higher and higher tax brackets, even though the buying power of their salary had stayed the same, or [had] gone down. This was great for the government (and is a big reason our deficits were not disastrous in the 1970s), but it was terrible for people, and led to the tax revolts that helped put Reagan in office.

But I digress. The point is that bracket creep made non-taxed benefits much more attractive relative to salary, so insurance started getting more generous. That process has continued for decades. Insurance used to be “major medical” that covered big ticket items like hospital stays. Now we expect it to cover the cost of going to the doctor for the sniffles. Well, if you insulate people from those costs, they will incur more of them.

Effectively, this raises demand for health care services. But the US system, decentralized and litigation-happy, is very bad at controlling the supply side. End result: high costs.

The other thing that happened is Medicare. The original legislation called for reimbursing services at “reasonable and customary rates”. This was a gold mine for doctors and hospitals. In New York, for example, doctors used to be forced to do charity care as the price of their admitting privileges at prestigious city hospitals. Once Medicare came into the picture, there was no need for that! Or to economize on beds; you could always find someone to fill them. Eventually, Medicare tried to crack down (http://reason.com/archives/2011/12/13/medicare-whac-a-mole), but by then, it was damned hard to cut physician and hospital incomes, in part because they had made decisions based on their — like building new hospitals with all private rooms — that couldn’t be undone. Our cost base is permanently higher, and politically, we have shown no will to slash provider incomes. So even though our growth rate is about average for the OECD, we’re growing from a much higher level.

Megan McArdle, “Ask Me Anything”, Reddit, 2017-04-10.