Few policies have origins as ugly as that of the minimum wage. “Progressive” intellectuals in the early 20th century supported the minimum wage because they believed it to be an effective policy detergent to help cleanse the gene pool of ‘undesirables.’ By pricing low-skilled, ‘undesirable’ workers out of jobs, ‘undesirables’ are less likely to successfully pro-create and to immigrate. The fact that the minimum wage, by pricing ‘undesirables’ out of work, thereby artificially raises the incomes of white workers was considered to be an added benefit of this social-engineering device.

The ethics of these early supporters of the minimum wage were despicable. But say this much for these racist, protectionist creeps: they understood economics better than do many people today (including some economists) who believe either that the law of demand is uniquely inoperative in the market for low-skilled workers or that the American market for low-skilled workers is monopsonized.* Each belief is as inexplicable as it is unsupportable.

* And monopsonization of the labor market is only a necessary condition for a minimum wage to not destroy employment opportunities for some workers; it is not a sufficient condition.

Don Boudreaux, “Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2016-06-01.

June 18, 2016

QotD: The origin of the push for a minimum wage

June 17, 2016

What If – Two Pivotal Moments of World War 1 I THE GREAT WAR Week 99

Published on 16 Jun 2016

This week 100 years ago the whole war hangs in the balance, the Germans are about to break through the lines at Verdun, the Russians actually break through the Austro-Hungarian lines but fail to seize the opportunity further north. It all boils down to the lack of communication between Erich von Falkenhayn and Conrad von Hötzendorf which created a situation in which Falkenhayn has to save Conrad’s Army and loses his momentum at Verdun.

QotD: That time that Jeremy Clarkson sabotaged a Reliant Robin for a Top Gear segment

Here’s what Clarkson confessed to the Sunday Times:

TO JUDGE from the letters I get and the remarks in the street, it seems the most memorable thing I did on Top Gear was a short segment about the Reliant Robin. You may remember: I drove it around Sheffield and it kept falling over.

Well, now’s the time to come clean. A normal Reliant Robin will not roll unless a drunken rugby team is on hand. Or it’s windy. But in a headlong drive to amuse and entertain, I’d asked the backroom boys to play around with the differential so that the poor little thing rolled over every time I turned the steering wheel.

Naturally, the health and safety department was very worried about this and insisted that the car be fitted with a small hammer that I could use, in case I was trapped after the roll, to break what was left of the glass.

Reliant sold plenty of cheap, usable little three-wheelers, and somehow managed to never be charged for crimes against humanity. The cars weren’t the most stable things in the world (no pointy-fronted three-wheeler is) but they certainly didn’t tumble around like a roofie’d Mary Lou Retton at every turn.

Jason Torchinsky, “Clarkson Reveals Bombshell: Top Gear Modified Reliant Robins To Make Them Roll”, Jalopnik, 2016-01-13.

June 16, 2016

Silent Victory now available in wargame format

I’m currently reading this two-volume history of the US Navy’s submarines in the Pacific during WW2 by Clay Blair, Jr., so I was interested to see this review of a wargame covering this exact conflict:

Consim Press has published a fantastic solo player wargame in Silent Victory: U.S. Submarines in the Pacific, 1941-1945. With game design by Gregory M. Smith, Silent Victory offers a little bit of everything for someone looking for an immersive, historical naval wargame that is easy to play yet detailed enough to be fulfilling for an advanced gamer.

It covers one of the biggest problems American sub commanders faced for the first two years of the war:

For every torpedo you fire, you’ll roll a 1d6 dice for a dud. Roll a 1 or 2, well, you are out of luck. It might have hit, but it didn’t explode. Dud. This happened to me at least three times in two patrols. It was a fact — the U.S. Navy had a torpedo problem. Clay Blair Jr.’s magisterial book Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War against Japan made this clear:

“…[T}he submarine force was hobbled by defective torpedoes. Developed in peacetime but never realistically tested against targets, the U.S. submarine torpedo was believed to be one of the most lethal weapons in the history of naval warfare. It had two exploders, a regular one that detonated it on contact with the side of an enemy ship and a very secret “magnetic exploder” that would detonate it beneath the keel of a ship without contact. After the war began, submariners discovered the hard way that the torpedo did not run steadily at the depth set into its controls and often went much deeper than designed, too deep for the magnetic exploder to work.”

Blair notes that not until late 1943 would the U.S. Navy fix the numerous torpedo problems.

Actually, the depth control issue was only the start of the problem. Once enough sub skippers had complained to their chain of command that the torpedoes were running too deep, and were able to get a few of them tested to prove it, then other problems became apparent. Even if the torpedo ran at the correct depth, the magnetic exploder would not reliably trigger the warhead when it passed under an enemy ship. The German and British submarine services had also developed similar exploders, but had abandoned them after wartime testing proved them to be ineffective. US Navy submarine admirals would not be convinced, so it took much longer for the sub captains to get permission to de-activate the magnetic exploders and use the contact exploders instead.

Unbelievably, it now became clear that there were also problems with the contact exploder as well, so even if it hit the side of the target it might not explode. American torpedoes had a significantly smaller warhead than those of other navies, because it had been expected that the magnetic exploder detonating below the keel of an enemy ship would be sufficient to break the back of the target and sink it. When used as ordinary torpedoes, it often took three or four hits to guarantee a sinking even on a merchant ship. Warships, having better compartmentalization, were even tougher to sink without lucky shots that hit fuel or ammunition compartments.

There are three reasons why this game succeeds.

First, historical accuracy. From the problems with torpedoes, to the detailed lists of Japanese merchant and capital ships, or to the specific weapons load out of each U.S. submarine in WWII, it is all there. The makers of this game did not cut any corners. They did their homework and tried, I think successfully, to incorporate significant historical facts into the gameplay.

Second, a risk/reward based gameplay experience. Every decision you make — from the torpedoes you use to deciding if you want to attack submerged and at close or long distance — incurs risk. There are numerous tradeoffs. For instance, you can attack from long distance submerged, but you suffer a roll modifier and risk not hitting your target. Or, you can be aggressive, and attack at close range, surfaced at night, which may increase your chance of hit but also increase your chance of detection. It just depends.

Finally, simple game rules. Complicated games are no fun to play. As a player, I don’t want to spend 10 minutes looking up rule after rule in a rulebook the size of a encyclopedia. In Silent Victory, the designers have done us a favor. The rules are clearly written and extensive, and after a single read through I referred to them occasionally. But more important, the combat mat has the dice roll encounter procedures printed on it, all within easy view. Also, the other mats all have reference numbers and clearly identify which dice should be rolled for what effects. It is all right there on the mats. This makes for a fun, smooth playing experience. And finally, if I were add another reason why this game is worth your money, it is the game’s replay value. You can conduct numerous patrols and no two patrols will ever be the same.

Silent Victory is a fun naval wargame that will appeal to the novice or expert gamer – and maybe you’ll learn something along the way.

Early Christian Schisms – III: The Council of Nicaea – Extra History

Published on 14 May 2016

The Council of Nicaea convened to decide the guiding rules of the church – and to resolve the questions posed by Arian theology. A deacon named Athanasius set himself against Arius and succeeded in getting his teachings declared heresy.

____________Disclaimer: This series is intended for students, to give them a broad overview of a complicated subject that has driven world history for centuries. Our story begins and focuses on Rome.

Constantine called the Council of Nicaea not only to address the teachings of Arius, but also to decide basic matters for how the church would go forward. Yet it was the debate over Arian theology which quickly came to dominate the council’s time. The bishops effectively split into two factions, one backing Arius and the other led by a deacon named Athanasius. Athanasius vehemently opposed the Arian teachings and would not allow any compromise to be formed with the other group. Yet he played the politics very carefully, adopting in his own arguments the phrase “homoousian” (or “of the same substance”) to describe the relationship between the Father and the Son, knowing full well that Arius would never accept an agreement which included this idea. Even when others tried to compromise with the phrase “homoiousian” (or “of similar substance”), Arius would not agree. Athanasius used the extra time to make private deals and assemble a majority coalition, with which he successfully caused Arianism to be declared heresy and forced Arius himself into exile. Emperor Constantine was just happy a decision had been reached, but a bishop in his own court would not let matters rest so easily. This bishop, Eusebius, campaigned tirelessly for the restoration of Arius and managed to get Athanasius exiled instead. Constantine himself wound up being baptized by Eusebius, and his son Emperor Constantius II would be a die-hard Arian in his turn. Eusebius even ordained a Goth named Ulfilas to preach to the Gothic tribes, and his sucess meant that the tribes became Arian Christians who would never completely assimilate into the Roman Empire. Thus, despite the firm decree at the First Council of Nicaea, Arian Christianity continued to grow and thrive alongside orthodox teachings.

QotD: Humanity’s near-infinite capacity for rationalization and self-deception

So how can an otherwise functional intellect close itself to all this irrefutable evidence and claim that the Holocaust was either a hoax or nowhere near as large in scope as claimed?

The answer, of course, lies in the nearly unlimited human capacity for self-deception. We are really, really good at both rationalizing our own preferences, and “explaining away” evidence that points to something we don’t want to be true. Denying Auschwitz is a piece of cake for someone with conviction when you consider that people can deny, on the spot, the reality of things that happen right then and there. That’s how you can have 9/11 truthers. That’s how you can have people claiming that the Charlie Hebdo attacks were a false flag operation perpetrated by a sinister race of “magical Jews” who can shape-shift. That’s why it doesn’t even matter if police officers wear body cameras — because you can videotape the most justified shooting of an armed perpetrator, and there will still be people who will watch the video and claim that the police officer executed someone in cold blood for no reason.

It’s because when you are invested in an ideology, you have to make reality subordinate to that ideology. And when the physical evidence points to the possibility that your ideology doesn’t match reality, then you have to deny that reality, or face the possibility that you ideology is wrong. It’s much easier to dismiss historical records or claim that a video was doctored than to examine your beliefs and concede that everything you believe is wrong.

But reality doesn’t go away when you deny it. Those buildings and crematoriums at Auschwitz still stand, and every time someone denies what they were used for, they deny the humanity of all the people who died there. And just as importantly, they deny the human ability to commit such atrocities, which in turn paves the way for a repeat of those atrocities. To borrow my friend Kathy’s words, there’s a world of difference between “Never Again” and “It can’t happen here.”

Because if a society of civilized, educated people, the nation of Goethe and Schiller and Beethoven, can build and staff a place like Auschwitz and systematically murder millions of people in just a few years — if orderly, fastidious Germans can go from bookkeeping to putting on a uniform and herding women and children into gas chambers at gunpoint because they perceive the approval of society and enjoy the power they are given — then it can happen anywhere, at any time.

Marko Kloos, “on the holocaust and self-deception”, the munchkin wrangler, 2015-01-28.

June 15, 2016

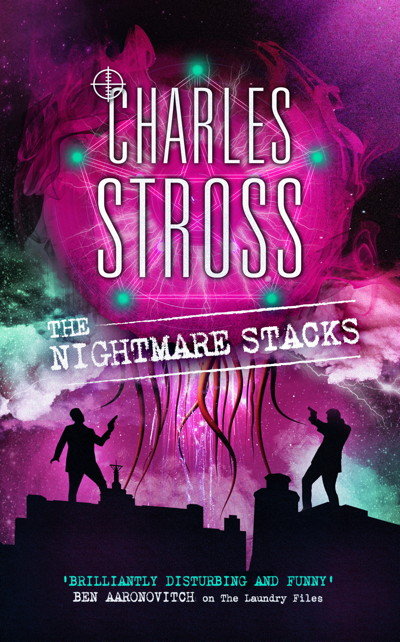

A sneak peak at The Nightmare Stacks by Charles Stross

If you’ve read any of the Laundry books, you’ll want to read the first chapter of the latest book in the series here.

If it follows the formal schedule, the book will go on sale on June 23rd in the UK, and the 28th in the US and Canada. You may see it offered a bit sooner in a few locations, depending on the vagaries of the book distribution system (and some retailers’ inability to keep to publication dates).

QotD: American secular puritanism

If there is one mental vice, indeed, which sets off the American people from all other folks who walk the earth … it is that of assuming that every human act must be either right or wrong, and that ninety-nine percent of them are wrong.

H.L. Mencken, “The American: His New Puritanism”, The Smart Set, 1914-02.

June 14, 2016

Beyond The Genocide – Armenia in WW1 I THE GREAT WAR Special

Published on 13 Jun 2016

The region of Armenia was a play ball between the interests of Russia and the Ottoman Empire long before World War 1. But the Armenian people were striving for self determination like the peoples all across Europe were doing too. In our special episode we take a look at the struggle of the Armenians beyond the Armenian Genocide.

Early Christian Schisms – II: The Woes of Constantine – Extra History

Published on 7 May 2016

Constantine had restored full rights to Christians in the Roman Empire with the Edict of Milan, but he did not expect theological debates to divide the church. Conflict between the orthodox church and both the Donatists and the Arians drew him to intervene.

____________Disclaimer: This series is intended for students, to give them a broad overview of a complicated subject that has driven world history for centuries. Our story begins and focuses on Rome.

Constantine had gained control of the Roman Empire, its first Christian emperor, and he restored full rights to people of the Christian faith with the Edict of Milan. But his generosity immediately raised a question: what did the church do with so-called traditors, who had renounced the Christian faith during the days of persecution and now wanted to return? The Roman Church demanded they be restored, because the doctrine of penance declared that anyone could repent for any sin, no matter how grievous. But in North Africa, one group was outraged when a traditor named Caecilian was not only restored to the faith but elected Bishop of Carthage. They refused to accept him and elected their own bishop, Donatus, instead. Donatus performed the role of a bishop without official church authority and he insisted on re-baptizing traditors in contradiction to the doctrine of penance. The church wanted to put him on trial, but since Donatus had rebelled against the people calling for his trial, he didn’t believe it would be a fair trial. He wrote Constantine asking for help and the emperor decided to intervene, setting a dangerous precedent for imperial involvement in affairs of the church. Over a series of several trials, church leaders continued to condemn Donatus and he continued to ask Constantine for retrials until the emperor grew fed up and washed his hands of the matter. The unrepentant Donatists went on to become a splinter church that divided North Africa for centuries. Around the same time, a bishop named Arius had begun to teach a view on the nature of the Father and the Son which contradicted the trinitarian belief in co-equal and co-substantial natures. The Bishop of Alexandria excommunicated him when his teachings attracted too many followers and again threatened to split the church. Since the debates continued to rage, Constantine sent a cleric to try and broker peace between the two sides – but the cleric he sent was a strident trinitarian who only tried to put down the Arian sect and sparked riots instead. That cleric attempted to call a local council to resolve the matter, but Constantine – well aware by now that his representative was probably laying a trap for the Arians – suggested instead that a universal council of bishops from across the empire be called together at Nicea.

QotD: Romantic love … what is it for?

It’s all about the encephalization, really. Millions of years ago our hominid ancestors stumbled onto a novel adaptive strategy: be smart, adaptable, and capable of learning rather than purely instinct-driven. Make tools; use fire; invent language.

This strategy required much, much more of our nervous systems. Because intelligence was in fact a winning strategy, we were selected for growing more complex brains capable of doing more information processing. But increasing the logic density of brains is hard; there probably isn’t a path to it through the design space that is rapidly exploitable by small point mutations. So selective pressure made our brains larger, instead.

The fossil record shows that the hominid line encephalized at a breakneck speed compared to the usual leisurely pace of evolutionary change. This had huge consequences; much of human biology is a series of hacks and kluges to support that encephalization, often in stupidly suboptimal ways.

The one that’s relevant here starts from the limited width of the birth canal. Limited, that is, by the pelvic girdle surrounding it. A skull that’s too large won’t fit through. Therefore, the genetic lines that survived were those in which babies are born with small skulls but the ability to grow them much larger by maturity. (And even so, the size of a baby’s skull pushes that limit pretty hard; this is why birth is so much more difficult and dangerous for human females than it is for other primates).

That design (be born with a small skull and upgrade it outside the womb) implied a long juvenile period between birth and physical maturity. In fact the human brain doesn’t completely finish configuring and rewiring itself until around age 25. And the long juvenile period probably also explains the exceptionally long human lifespan; whatever had to be altered in the development clock to defer stabilization into the final adult configuration probably also delayed the inset of senescence. (Direct evidence for this theory is the rare disease “progeria”).

And the dominoes kept falling. The long juvenile period implied offspring that would be incapable of fending for themselves for an unprecedently long time – on the order of decades rather than the few months to a year typical for other mammals. Consequently the selective value of extended cooperation between the parents went way, way up relative to even our nearest animal kin.

Romantic love works as an an evolved mechanism for keeping mated pairs cooperating long enough to raise multiple children. Here again, selection favors those who love more because they get to launch more offspring. We are, in fact, made to fall in love – and it would only be surprising if the mechanism for establishing it were not simple, robust, and easily triggered.

Eric S. Raymond, “Love is the simplest thing”, Armed and Dangerous, 2015-01-15.

June 13, 2016

Coming soon – “the most serious constitutional crisis since the Abdication of King Edward VIII”

In the Daily Mail, Peter Hitchins rubs his hands in glee at the implications of the surge in popularity of the Brexiteers:

I think we are about to have the most serious constitutional crisis since the Abdication of King Edward VIII. I suppose we had better try to enjoy it.

If – as I think we will – we vote to leave the EU on June 23, a democratically elected Parliament, which wants to stay, will confront a force as great as itself – a national vote, equally democratic, which wants to quit. Are we about to find out what actually happens when an irresistible force meets an immovable object?

I am genuinely unsure how this will work out. I hope it will only destroy our two dead political parties, stiffened corpses that have long propped each other up with the aid of BBC endorsement and ill-gotten money.

I was wrong to think that the EU referendum would be so hopelessly rigged that the campaign for independence was doomed to lose. I overestimated the Prime Minister – a difficult thing for me to do since my opinion of him was so low. I did not think he could possibly have promised this vote with so little thought, preparation or skill.

I underestimated the BBC, which has, perhaps thanks to years of justified and correct criticism from people such as me, taken its duty of impartiality seriously.

Everything I hear now suggests that the votes for Leave are piling up, while the Remain cause is faltering and floundering. The betrayed supporters of both major parties now feel free to take revenge on their smug and arrogant leaders.

Moving really is hell

In the New York Post, Naomi Schaefer Riley reports that Americans are apparently moving less frequently than they used to, and at least part of the reason is the hellish experience of moving:

Americans are stuck. Research from the Census Bureau suggests that Americans have stepped in some wet cement and have yet to extract themselves.

In 1948, more than 20 percent of Americans moved to a new home. But that percentage has been steadily declining since the ’80s, to the point where now only 11 percent of Americans say they have moved in the last year.

Experts have offered all sorts of reasons for this immobility. But for some of us, anyway, there’s the unavoidable fact that moving is a pain in the behind. It’s expensive and time-consuming — and it seems to be getting worse. When I tell friends that our family is moving this week, they look at me as if I’ve just told them a family pet has died.

When my parents sold a house three decades ago, they were told to “straighten up.” But now our homes are expected to be immaculate displays. There are people who make their living “staging homes,” as if we should put on some kind of theatrical performance in order to get top dollar.

Real estate agents will give you piles of material to explain what to do to a house to make it “show ready.” (That “show” is apparently “House Hunters.”) “Make your house look like a Pottery Barn catalogue,” one agent explained. “Only three to four books are allowed on any shelf.”

Apparently people in Pottery Barn catalogues don’t read. Also, their children don’t have Legos.

We moved house earlier this year and we’re still digging out from underneath the rubble. It didn’t help that we found the perfect house to buy long before we expected to, and so hadn’t begun any kind of prep work in our existing house in advance of the move. We were trading a larger home in a 15-year-old suburb for a house in a small town that was nearly 200 years old. That translates to not only smaller living space (about 1000 square feet less) but also little to no storage space (closets were extremely rare in the 1830s). We’d been 13 years in the house and our stuff had “settled” around us … we could have used six months to de-clutter, pare down our less-frequently-used possessions, and make regular trips to the dump. Oh, and my sudden health issue and two-week stay in ICU almost exactly in the middle of the packing phase really didn’t help at all.

We moved out in phases, clearing out most of our stuff from the interior of the house, but leaving the garage and basement stuffed with anything we couldn’t get packed in time for the movers to take. We had much of the interior of the house repainted (actually, we had both the houses repainted), plus new carpeting upstairs and lots of “handyman” fixes to try to erase as much of the bumps and dings of having actually lived in the place for more than a decade. Then the real estate agent brought in the staging crew and decorated the place. After that was done, we barely recognized it, but while the furnishings and decorations were visually attractive, it was clearly not the kind of usage any normal family would have for the space.

Fortunately, our house did sell fairly quickly for just a bit less than our original asking price, but remember all the crap we stashed away in the garage and the basement? We only just finished clearing that out the same day we had to hand the keys over to our lawyers prior to the sale closing. Where did it all go? Most of it ended up in what I eventually plan to be my woodworking shop in the garage. Lots of the rest ended up going to the dump. I lost track of the total number of dump runs we made … and I know there’s probably more that will need to go that route as we begin to unpack the remaining boxes.

After all that, I really understand the attraction of minimalism but I know I could never live that way: between my thousands of books and my woodworking tools and materials there’s no way to be truly “minimal”. For example, while the garage is currently filled to the brim with “stuff”, my table saw and other woodworking power tools are in a storage locker because there’s no room for them in the shop (yet).

Of course, on a warm spring afternoon, just looking out over the backyard reminds me that the move was worth it:

QotD: The absurdities of many occupational licenses

In 2012, the Institute for Justice — a public-interest law firm advocating libertarian causes — looked at the number of occupations that require licensing. Specifically, the institute looked at occupations typically filled by lower- and middle-income workers. These are not your airline pilots, your certified public accountants and your neurosurgeons; they’re the nations interior decorators, auctioneers and florists. (Yes, you read that right: In at least one state, these occupations cannot be practiced without a license.)

Why, you might ask, is the state requiring a license to decorate an interior? Are customers at risk of death from collapsing piles of pillow shams? Must we fear that they will be blinded by the decorator’s decision to pair fuchsia chiffon drapes with a chartreuse brocade sofa? Do we worry that without the threat of losing their license to keep them on the straight and narrow, these fly-by-night operators might be tempted into purchasing furniture from unlicensed auctioneers, and sourcing their floral arrangements from black-market florists?

Well, no. Mostly, these regulations benefit folks who are already plying the trade. They get helpful state legislators to protect them from competition by instituting tough licensing requirements. Their income goes up; the consumer’s wallet suffers. And people who want to follow their dreams into the industry get shut out if they lack the time to study for the licensing exams, the capital to pay the licensing exam fees (which can run in to the hundreds of dollars), or the social capital to know how to work the system.

Megan McArdle, “You’re Gonna Need a License for That”, Bloomberg View, 2016-05-17.

June 12, 2016

Cossacks – Cavalry – Wolves I OUT OF THE TRENCHES

Published on 11 Jun 2016

Indy sits in the Chair of Wisdom again and this week we talk about Cavalry on the Eastern Front, Cossacks and wolves.