[News of the wider world travels very slowly from the Royal court to the outskirts, but] information velocity within the sticks […] is very high. Nobody cares much who this “Richard II” cat was, or knows anything about ol’ Whatzisface – Henry Something-or-other – who might’ve replaced him, but everyone knows when the local knight of the shire dies, and everything about his successor, because that matters. So, too, is information velocity high at court – the lords who backed Henry Bolingbroke over Richard II did so because Richard’s incompetence had their asses in a sling. They were the ones who had to depose a king for incompetence, without admitting, even for a second, that

a) competence is a criterion of legitimacy, and

b) someone other than the king is qualified to judge a king’s competence.Because admitting either, of course, opens the door to deposing the new guy on the same grounds, so unless you want civil war every time a king annoys one of his powerful magnates, you’d best find a way to square that circle …

… which they did, but not completely successfully, because within two generations they were back to deposing kings for incompetence. Turns out that’s a hard habit to break, especially when said kings are as incompetent as Henry VI always was, and Edward IV became. Only the fact that the eventual winner of the Wars of the Roses, Henry VII, was as competent as he was as ruthless kept the whole cycle from repeating.

Severian, “Inertia and Incompetence”, Founding Questions, 2020-12-25.

October 16, 2023

QotD: Differentials of “information velocity” in a feudal society

October 15, 2023

History Summarized: The Castles of Wales

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 23 Jun 2023Every castle tells a story, but when one small country has over 600 castles, the collective story they tell is something like “holy heck ouch, ow, oh god, why are there so many arrows, ouch, good lord ow” – And that’s Wales for you.

(more…)

October 11, 2023

QotD: A rational army would run away …

It is a thousand years ago somewhere in Europe; you are one of a line of ten thousand men with spears. Coming at you are another ten thousand men with spears, on horseback. You do a very fast cost-benefit calculation.

If all of us plant our spears and hold them steady, with luck we can break their charge; some of us will die but most of us will live. If we run, horses run faster than we do. I should stand.

Oops.

I made a mistake; I said “we”. I don’t control the other men. If everybody else stands and I run, I will not be the one of the ones who gets killed; with 10,000 men in the line, whether I run has very little effect on whether we stop their charge. If everybody else runs I had better run too, since otherwise I’m dead.

Everybody makes the same calculation. We all run, most of us die.

Welcome to the dark side of rationality.

This is one example of what economists call market failure — a situation where individual rationality does not lead to group rationality. Each person correctly calculates how it is in his interest to act and everyone is worse off as a result.

David D. Friedman, “Making Economics Fun: Part I”, David Friedman’s Substack, 2023-04-02.

October 10, 2023

September 26, 2023

QotD: Bad kings, mad kings, and bad, mad kings

An incompetent king doesn’t invalidate the very notion of monarchy, as monarchs are men and men are fallible. A bad, mad king (or a minor child) would surely find himself sidelined, or suffering an unfortunate hunting accident, or in extreme cases deposed, but the process of replacing X with Y on the throne didn’t invalidate monarchy per se. Deposing a king for incompetence was a very dangerous maneuver for lots of reasons, but it could be, and was, recast as a kind of “mandate of heaven” thing. Though they of course didn’t say that, the notion wasn’t a particularly tough sell in the age of Avignon and Antipopes.

But notice the implied question here: Sold to whom?

That’s where the idea of “information velocity” comes in. Exaggerating only a little for effect: Most subjects of most monarchs in the Medieval period had only the vaguest idea of who the king even was. Yeah, sure, theoretically you know that your lord’s lord’s lord owes homage to some guy called “Edward II” – that whole “feudal pyramid” thing – but as to who he might be, who cares? You’ll never lay eyes on the guy, except maybe as a face on a coin … and when will you ever even see one of those? So when you finally hear, weeks or months or years after the fact, that “Richard II” has been deposed, well … vive le roi, I guess. Meet the new boss, same as the old boss, and meanwhile life goes on the same as it ever did.

Information velocity out to the sticks, in other words, was very low. By the time you find out what the great and the good are up to, it’s already over. And, of course, the reverse – so long as the taxes come in on time, on the rare occasions they’re levied (imagine that!), the king doesn’t much care what his vassal’s vassals’ vassals’ vassals are up to.

Severian, “Inertia and Incompetence”, Founding Questions, 2020-12-25.

September 19, 2023

The end of the Western Roman Empire

Theophilus Chilton updates a review from several years ago with a few minor changes:

British archaeologist and historian Bryan Ward-Perkin’s excellent 2005 work The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization is a text that is designed to be a corrective for the type of bad academic trends that seem to entrench themselves in even the most innocuous of subjects. In this case, Ward-Perkins, along with fellow Oxfordian Peter Heather in his book The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, sets out to fix a glaring error which has come to dominate much of the scholarly study of the 4th and 5th centuries in the western Empire for the past few decades.

This error is the view that the western Empire did not actually “fall”. Instead, so say many latter-day historical revisionists, what happened between the Gothic victory at Adrianople in 378 AD and the abdication of Romulus Augustulus, the last western Emperor, in 476 was more of an accident, an unintended consequence of a few boisterous but well-meaning neighbors getting a bit out of hand. Challenged is the very notion that the Germanic tribes (who cannot be termed “barbarians” any longer) actually “invaded”. Certainly, these immigrants did not cause harm to the western Empire — for the western empire wasn’t actually “destroyed”, but merely “transitioned” seamlessly into the era we term the Middle Ages. Ward-Perkins cites one American scholar who goes so far as to term the resettlement of Germans onto land that formerly belonged to Italians, Hispanians, Britons, and Gallo-Romans as taking place “in a natural, organic, and generally eirenic manner”. Certainly, it is gauche among many modern academics in this field to maintain that violent barbarian invasions forcibly ended high civilization and reduced the living standards in these regions to those found a thousand years before during the Iron Age.

Ward-Perkins points out the “whys” of this historical revision. Much of it simply has to do with political correctness (which he names as such) — the notion that we cannot really say that one culture is “higher” or “better” than others. Hence, when the one replaces the other, we cannot speculate as to how this replacement made things worse for all involved. In a similar vein, many continental scholars appear to be uncomfortable with the implications that the story of mass barbarian migrations and subsequent destruction and decivilization has in the ongoing discussion about the European Union’s own immigration policy — a discussion in which many of these same academics fall on the left side of the aisle.

Yet, all of this revisionism is bosh and bunkum, as Ward-Perkins so thoroughly points out. He does this by bringing to the table a perspective that many other academics in this field of study don’t have — that of a field archaeologist who is used to digging in the dirt, finding artifacts, drawing logical conclusions from the empirical evidence, and then using that evidence to decide “what really happened”, rather than just literary sources and speculative theories. Indeed, as the author shows, across the period of the Germanic invasions, the standard of living all across Roman western Europe declined, in many cases quite precipitously, from what it had been in the 3rd century. The quality and number of manufactured goods declined. Evidence for the large-scale integrative trade network that bound the western Empire together and with the rest of the Roman world disappears. In its place we find that trade goods travelled much smaller distances to their buyers — evidence for the breakdown of the commercial world of the West. Indeed, the economic activity of the West disappeared to the point that the volume of trade in western Europe would not be matched again until the 17th century. Evidence for the decline of food production suggests that populations fell all across the region. Ward-Perkins’ discussion of the decline in the size of cattle is enlightening evidence that the degeneration of the region was not merely economic. Economic prosperity, the access of the common citizen to a high standard of living with a wide range of creature comforts, disappeared during this period.

The author, however, is not negligent in pointing out the literary and documentary evidence for the horrors of the barbarian invasions that so many contemporary scholars seem to ignore. Indeed, the picture painted by the sum total of these evidences is one of harrowing destruction caused by aggressive, ruthless invaders seeking to help themselves to more than just a piece of the Roman pie. Despite the recent scholarly reconsiderations, the Germans, instead of settling on the land given to them by various Emperors and becoming good Romans, ended up taking more and more until there was nothing left to take. As Ward-Perkins puts it,

Some of the recent literature on the Germanic settlements reads like an account of a tea party at the Roman vicarage. A shy newcomer to the village, who is a useful prospect for the cricket team, is invited in. There is a brief moment of awkwardness, while the host finds an empty chair and pours a fresh cup of tea; but the conversation, and village life, soon flow on. The accommodation that was reached between invaders and invaded in the fifth- and sixth- century West was very much more difficult, and more interesting, than this. The new arrival had not been invited, and he brought with him a large family; they ignored the bread and butter, and headed straight for the cake stand. Invader and invaded did eventually settle down together, and did adjust to each other’s ways — but the process of mutual accommodation was painful for the natives, was to take a very long time, and, as we shall see …left the vicarage in very poor shape. (pp. 82-83)

Professor Bret Devereaux discussed the long fifth century on his blog last year:

… it is not the case that the Roman Empire in the west was swept over by some destructive military tide. Instead the process here is one in which the parts of the western Roman Empire steadily fragment apart as central control weakens: the empire isn’t destroy[ed] from outside, but comes apart from within. While many of the key actors in that are the “barbarian” foederati generals and kings, many are Romans and indeed […] there were Romans on both sides of those fissures. Guy Halsall, in Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West (2007) makes this point, that the western Empire is taken apart by actors within the empire, who are largely committed to the empire, acting to enhance their own position within a system the end of which they could not imagine.

It is perhaps too much to suggest the Roman Empire merely drifted apart peacefully – there was quite a bit of violence here and actors in the old Roman “center” clearly recognized that something was coming apart and made violent efforts to put it back together (as Halsall notes, “The West did not drift hopelessly towards its inevitable fate. It went down kicking, gouging and screaming”) – but it tore apart from the inside rather than being violently overrun from the outside by wholly alien forces.

September 12, 2023

QotD: The largest input for producing iron in pre-industrial societies

… let’s start with the single largest input for our entire process, measured in either mass or volume – quite literally the largest input resource by an order of magnitude. That’s right, it’s … Trees

The reader may be pardoned for having gotten to this point expecting to begin with exciting furnaces, bellowing roaring flames and melting all and sundry. The thing is, all of that energy has to come from somewhere and that somewhere is, by and large, wood. Now it is absolutely true that there are other common fuels which were probably frequently experimented with and sometimes used, but don’t seem to have been used widely. Manure, used as cooking and heating fuel in many areas of the world where trees were scarce, doesn’t – to my understanding – reach sufficient temperatures for use in iron-working. Peat seems to have similar problems, although my understanding is it can be reduced to charcoal like wood; I haven’t seen any clear evidence this was often done, although one assumes it must have been tried.

Instead, the fuel I gather most people assume was used (to the point that it is what many video-game crafting systems set for) was coal. The problem with coal is that it has to go through a process of coking in order to create a pure mass of carbon (called “coke”) which is suitable for use. Without that conversion, the coal itself both does not burn hot enough, but also is apt to contain lots of sulfur, which will ruin the metal being made with it, as the iron will absorb the sulfur and produce an inferior alloy (sulfur makes the metal brittle, causing it to break rather than bend, and makes it harder to weld too). Indeed, the reason we know that the Romans in Britain experimented with using local coal this way is that analysis of iron produced at Wilderspool, Cheshire during the Roman period revealed the presence of sulfur in the metal which was likely from the coal on the site.

We have records of early experiments with methods of coking coal in Europe beginning in the late 1500s, but the first truly successful effort was that of Abraham Darby in 1709. Prior to that, it seems that the use of coal in iron-production in Europe was minimal (though coal might be used as a fuel for other things like cooking and home heating). In China, development was more rapid and there is evidence that iron-working was being done with coke as early as the eleventh century. But apart from that, by and large the fuel to create all of the heat we’re going to need is going to come from trees.

And, as we’ll see, really quite a lot of trees. Indeed, a staggering number of trees, if iron production is to be done on a major scale. The good news is we needn’t be too picky about what trees we use; ancient writers go on at length about the very specific best woods for ships, spears, shields, or pikes (fir, cornel, poplar or willow, and ash respectively, for the curious), but are far less picky about fuel-woods. Pinewood seems to have been a consistent preference, both Pliny (NH 33.30) and Theophrastus (HP 5.9.1-3) note it as the easiest to use and Buckwald (op cit.) notes its use in medieval Scandinavia as well. But we are also told that chestnut and fir also work well, and we see a fair bit of birch in the archaeological record. So we have our trees, more or less.

Bret Devereaux, “Iron, How Did They Make It? Part II, Trees for Blooms”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-09-25.

September 8, 2023

QotD: Rents and taxes in pre-modern societies

In most ways […] we can treat rent and taxes together because their economic impacts are actually pretty similar: they force the farmer to farm more in order to supply some of his production to people who are not the farming household.

There are two major ways this can work: in kind and in coin and they have rather different implications. The oldest – and in pre-modern societies, by far the most common – form of rent/tax extraction is extraction in kind, where the farmer pays their rents and taxes with agricultural products directly. Since grain (threshed and winnowed) is a compact, relatively transportable commodity (that is, one sack of grain is as good as the next, in theory), it is ideal for these sorts of transactions, although perusing medieval manorial contacts shows a bewildering array of payments in all sorts of agricultural goods. In some cases, payment in kind might also come in the form of labor, typically called corvée labor, either on public works or even just farming on lands owned by the state.

The advantage of extraction in kind is that it is simple and the initial overhead is low. The state or large landholders can use the agricultural goods they bring in in rents and taxes to directly sustain specialists: soldiers, craftsmen, servants, and so on. Of course the problem is that this system makes the state (or the large landholder) responsible for moving, storing and cataloging all of those agricultural goods. We get some sense of how much of a burden this can be from the prominence of what seem to be records of these sorts of transactions in the surviving writing from the Bronze Age Near East (although I should note that many archaeologists working on the ancient Near Eastern economy are pushing for a somewhat larger, if not very large, space for market interactions outside of the “temple economy” model which has dominated the field for quite some time). This creates a “catch” we’ll get back to: taxation in kind is easy to set up and easier to maintain when infrastructure and administration is poor, but in the long term it involves heavier administrative burdens and makes it harder to move tax revenues over long distances.

Taxation in coin offers potentially greater efficiency, but requires more particular conditions to set up and maintain. First, of course, you have to have coinage. That is not a given! Much of the social interactions and mechanics of farming I’ve presented here stayed fairly constant (but consult your local primary sources for variations!) from the beginnings of written historical records (c. 3,400 BC in Mesopotamia; varies place to place) down to at least the second agricultural revolution (c. 1700 AD in Europe; later elsewhere) if not the industrial revolution (c. 1800 AD). But money (here meaning coinage) only appears in Anatolia in the seventh century BC (and probably independently invented in China in the fourth century BC). Prior to that, we see that big transactions, like long-distance trade in luxuries, might be done with standard weights of bullion, but that was hardly practical for a farmer to be paying their taxes in.

Coinage actually takes even longer to really influence these systems. The first place coinage gets used is where bullion was used – as exchange for big long-distance trade transactions. Indeed, coinage seemed to have started essentially as pre-measured bullion – “here is a hunk of silver, stamped by the king to affirm that it is exactly one shekel of weight”. Which is why, by the by, so many “money words” (pounds, talents, shekels, drachmae, etc.) are actually units of weight. But if you want to collect taxes in money, you need the small farmers to have money. Which means you need markets for them to sell their grain for money and then those merchants need to be able to sell that grain themselves for money, which means you need urban bread-eaters who are buying bread with money, which means those urban workers need to be paid in money. And you can only get any of these people to use money if they can exchange that money for things they want, which creates a nasty first-mover problem.

We refer to that entire process as monetization – when I talk about economies being “monetized” or “incompletely monetized” that’s what I mean: how completely has the use of money penetrated through this society. It isn’t a one-way street, either. Early and High Imperial Rome seem to have been more completely monetized than the Late Roman Western Empire or the early Middle Ages (though monetization increases rapidly in the later Middle Ages).

Extraction, paradoxically, can solve the first mover problem in monetization, by making the state the first mover. If the state insists on raising taxes in money, it forces the farmers to sell their grain for money to pay the tax-man; the state can then take that money and use it to pay soldiers (almost always the largest budget-item in an ancient or medieval state budget), who then use the money to buy the grain the farmers sold to the merchants, creating that self-sustaining feedback loop which steadily monetizes the society. For instance, Alexander the Great’s armies – who expected to be paid in coin – seem to have played a major role in monetizing many of the areas they marched through (along with breaking things and killing people; the image of Alexander the Great’s conquests in popular imagination tend to be a lot more sanitized).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part IV: Markets, Merchants and the Tax Man”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-08-21.

August 17, 2023

“… the Chinese invented gunpowder and had it for six hundred years, but couldn’t see its military applications and only used it for fireworks”

John Psmith would like to debunk the claim in the headline here:

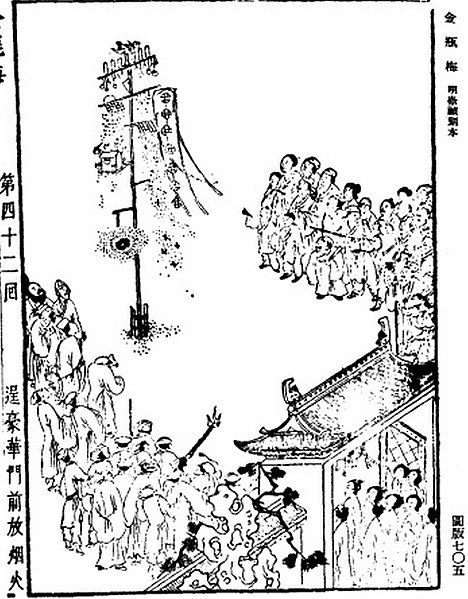

An illustration of a fireworks display from the 1628-1643 edition of the Ming dynasty book Jin Ping Mei (1628-1643 edition).

Reproduced in Joseph Needham (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7: Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press. Page 142.

There’s an old trope that the Chinese invented gunpowder and had it for six hundred years, but couldn’t see its military applications and only used it for fireworks. I still see this claim made all over the place, which surprises me because it’s more than just wrong, it’s implausible to anybody with any understanding of human nature.

Long before the discovery of gunpowder, the ancient Chinese were adept at the production of toxic smoke for insecticidal, fumigation, and military purposes. Siege engines containing vast pumps and furnaces for smoking out defenders are well attested as early as the 4th century. These preparations often contained lime or arsenic to make them extra nasty, and there’s a good chance that frequent use of the latter substance was what enabled early recognition of the properties of saltpetre, since arsenic can heighten the incendiary effects of potassium nitrate.

By the 9th century, there are Taoist alchemical manuals warning not to combine charcoal, saltpetre, and sulphur, especially in the presence of arsenic. Nevertheless the temptation to burn the stuff was high — saltpetre is effective as a flux in smelting, and can liberate nitric acid, which was of extreme importance to sages pursuing the secret of longevity by dissolving diamonds, religious charms, and body parts into potions. Yes, the quest for the elixir of life brought about the powder that deals death.

And so the Chinese invented gunpowder, and then things immediately began moving very fast. In the early 10th century, we see it used in a primitive flame-thrower. By the year 1000, it’s incorporated into small grenades and into giant barrel bombs lobbed by trebuchets. By the middle of the 13th century, as the Song Dynasty was buckling under the Mongol onslaught, Chinese engineers had figured out that raising the nitrate content of a gunpowder mixture resulted in a much greater explosive effect. Shortly thereafter you begin seeing accounts of truly destructive explosions that bring down city walls or flatten buildings. All of this still at least a hundred years before the first mention of gunpowder in Europe.

Meanwhile, they had also been developing guns. Way back in the 950s (when the gunpowder formula was much weaker, and produced deflagarative sparks and flames rather than true explosions), people had already thought to mount containers of gunpowder onto the ends of spears and shove them in peoples’ faces. This invention was called the “fire lance”, and it was quickly refined and improved into a single-use, hand-held flamethrower that stuck around until the early 20th century.1 But some other inventive Chinese took the fire lances and made them much bigger, stuck them on tripods, and eventually started filling their mouths with bits of iron, broken pottery, glass, and other shrapnel. This happened right around when the formula for gunpowder was getting less deflagarative and more explosive, and pretty soon somebody put the two together and the cannon was born.

All told it’s about three and a half centuries from the first sage singing his eyebrows, to guns and cannons dominating the battlefield.2 Along the way what we see is not a gaggle of childlike orientals marvelling over fireworks and unable to conceive of military applications. We also don’t see an omnipotent despotism resisting technological change, or a hidebound bureaucracy maintaining an engineered stagnation. No, what we see is pretty much the opposite of these Western stereotypes of ancient Chinese society. We see a thriving ecosystem of opportunistic inventors and tacticians, striving to outcompete each other and producing a steady pace of technological change far beyond what Medieval Europe could accomplish.

Yet despite all of that, when in 1841 the iron-sided HMS Nemesis sailed into the First Opium War, the Chinese were utterly outclassed. For most of human history, the civilization cradled by the Yellow and the Yangtze was the most advanced on earth, but then in a period of just a century or two it was totally eclipsed by the upstart Europeans. This is the central paradox of the history of Chinese science and technology. So … why did it happen?

1. Needham says he heard of one used by pirates in the South China Sea in the 1920s to set rigging alight on the ships that they boarded.

2. I’ve left out a ton of weird gunpowder-based weaponry and evolutionary dead ends that happened along the way, but Needham’s book does a great job of covering them.

August 15, 2023

QotD: Iron ore processing in pre-industrial societies

Once our ore reaches the surface (or is removed from its open pit) it is not immediately ready for smelting, but has to go through a series of preparatory steps collectively referred to as “dressing” to get the ore ready for its date with the smelter […]

Ore removed from the mine would need to be crushed, with the larger stones pulled out of the mines smashed with heavy hammers (against a rock surface) in order to break them down to a manageable size. The exact size of the ore chunks desired varies based on the metal one is seeking and the quality of the local ore. Ores of precious metals, it seems, were often ground down to powder, but for iron ore it seems like somewhat larger chunks were acceptable. I’ve seen modern experiments with bloomeries […] getting pretty good results from ore chunks about half the size of a fist. Interestingly, Craddock notes that ore-crushing activity at mines was sufficiently intense that archaeologists can spot the tell-tale depressions where the rock surface that provided the “floor” against which the ore was crushed have been worn by repeated use.

Ore might also be washed, that is passed through water to liberate and wash away any lighter waste material. Washing is attested in the ancient world for gold and silver ores (and by Georgius Agricola for the medieval period for the same), but might be used for other ores depending on the country rock to wash away impurities. The simple method of this, sometimes called jigging, consisted of putting the ore in a sieve and shaking it while water passed through, although more complex sluicing systems are known, for instance at the Athenian silver mines at Laurium (note esp. Healy, 144-8 for diagrams); the sluices for washing are sometimes called buddles. Throughout these processes, the ore would also probably be hand-sorted in an effort to separate high-grade ore from low-grade ore.

It’s clear that this mechanical ore preparation was much more intensive for higher-value metals where making sure to be as efficient as possible was a significant concern; gold and silver ores might be crushed, sorted, washed and rewashed before being ground into a powder for the final smelting process. Craddock presents a postulated processing set for copper ore for the Bronze Age Timna mines that goes through a primary crushing, hand-sorted division into three grades, secondary crushing, grinding, a winnowing step for the low-grade ore (either air winnowing or washing) before being blended into the final smelter “charge”.

As far as I can tell, such extensive processing for iron was much less common; in many cases it seems it is hard to be certain because the sources remain so focused on precious metal mining and the later stages of iron-working. Diodorus describes the iron ore on Elba as merely being crushed, roasted and then bloomed (5.13.1) but the description is so brief it is possible that he is leaving out steps (but also, Elba’s iron ore was sufficiently rich that further processing may not have been necessary). In many cases, iron was probably just crushed, sorted and then moved straight to roasting […]

Bret Devereaux, “Iron, How Did They Make It? Part I, Mining”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-09-18.

August 11, 2023

QotD: Subsistence versus market-oriented farming in pre-modern societies

Large landholders interacted with the larger number of small farmers (who make up the vast majority of the population, rural or otherwise) by looking to trade access to their capital for the small farmers’ labor. Rather than being structured by market transactions (read: wage labor), this exchange was more commonly shaped by cultural and political forces into a grossly unequal exchange whereby the small farmers gathered around the large estate were essentially the large landholder’s to exploit. Nevertheless, that exploitation and even just the existence of the large landholder served to reorient production away from subsistence and towards surplus, through several different mechanisms.

Remember: in most pre-modern societies, the small farmers are largely self-sufficient. They don’t need very many of the products of the big cities and so – at least initially – the market is a poor mechanism to induce them to produce more. There simply aren’t many things at the market worth the hours of labor necessary to get them – not no things, but just not very many (I do want to stress that; the self-sufficiency of subsistence farmers is often overstated in older scholarship; Erdkamp (2005) is a valuable corrective here). Consequently, doing anything that isn’t farming means somehow forcing subsistence farmers to work more and harder in order to generate the surplus to provide for those people who do the activities which in turn the subsistence farmers might benefit from not at all. But of course we are most often interested in exactly all of those tasks which are not farming (they include, among other things, literacy and the writing of history, along with functionally all of the events that history will commemorate until quite recently) and so the mechanisms by which that surplus is generated matter a great deal.

First, the large landholder’s farm itself existed to support the landholder’s lifestyle rather than his actual subsistence, which meant its production had to be directed towards what we might broadly call “markets” (very broadly understood). Now many ancient and even medieval agricultural writers will extol the value of a big farm that is still self-supporting, with enough basic cereal crops to subsist the labor force, enough grazing area for animals to provide manure and then the rest of the land turned over to intensive cash-cropping. But this was as much for limiting expenses to maximize profits (a sort of mercantilistic maximum-exports/minimum-imports style of thinking) as it was for developing self-sufficiency in a crisis. Note that we (particularly in the United States) tend to think of cash crops as being things other than food – poppies, cotton, tobacco especially. But in many cases, wheat might be the cash crop for a region, especially for societies with lots of urbanism; good wheat land could bring in solid returns […]. The “cash” crop might be grapes (for wine) or olives (mostly for olive oil) or any number of other necessities, depending on what the local conditions best supported (and in some cases, it could be a cash herd too, particularly in areas well-suited to wool production, like parts of medieval Britain).

Second, the exploitation by the large landholder forces the smaller farmers around him to make more intensive use of their labor. Because they are almost always in debt to the fellow with the big farm and because they need to do labor to get access to plow teams, manure, tools, or mills and because the large landholder’s land-ready-for-sharecropping is right there, the large landholder both creates the conditions that impel small farmers to work more land (and thus work more days) than their own small farms do and also creates the conditions where they can farm more intensively (both their own lands and the big farm’s lands, via plow teams, manure, etc.). Of course the large landholder then generally immediately extracts that extra production for his own purposes. […] all of the folks who aren’t small farmers looking to try to get small farmers to work harder than is in their interest in order to generate surplus. In this case, all of that activity funnels back into sustaining the large landholder’s lifestyle (which often takes place in town rather than in the countryside), which in turn supports all sorts of artisans, domestics, crafters and so on.

And so the large landholder needs the small subsistence farmers to provide flexible labor and the small subsistence farmers (to a lesser but still quite real degree) need the large landholder to provide flexibility in capital and work availability and the interaction of both of these groups serves to direct more surplus into activities which are not farming.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part II: Big Farms”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-07-31.

July 25, 2023

QotD: Non-free farm labourers in pre-modern agriculture

The third complicated category of non-free laborers is that of workers who had legal control of their persons to some degree but who were required by law and custom to work on a given parcel of land and give some of the proceeds to their landlord. By way of example, under the reign of Diocletian (284-305), in a (failed) effort to reform the tax-system, the main class of Roman tenants, called coloni (lit: “tillers”), were legally prevented from moving off of their estates (so as to ensure that the landlords who were liable for taxes on that land would be in a position to pay). That this change does not seem to have been a massive shift at the time should give some sense of how low the status of these coloni had fallen and just how powerful a landlord might be over their tenants. That system in turn (warning: substantial but necessary simplification incoming) provided the basis for later European serfdom. Serfs were generally tied to the land, being bought and sold with it, with traditional (and hereditary) duties to the owner of the land. They might owe a portion of their produce (like tenants) or a certain amount of labor to be performed on land whose proceeds went directly to the landlord. While serfs generally had more rights (particularly in the protection and self-ownership of their persons) than enslaved persons, they were decidedly non-free (they couldn’t, by law, move away generally) and their condition was often quite poor when compared to even small freeholders. Non-free labor was generally not flexible (the landholder was obliged to support these folks year-round whether they had work to do or not) and so composed the fixed core labor of the large landholder’s holdings.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part II: Big Farms”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-07-31.

June 24, 2023

QotD: The plight of miners in pre-industrial societies

Essentially the problem that miners faced was that while mining could be a complex and technical job, the vast majority of the labor involved was largely unskilled manual labor in difficult conditions. Since the technical aspects could be handled by overseers, this left the miners in a situation where their working conditions depended very heavily on the degree to which their labor was scarce.

In the ancient Mediterranean, the clear testimony of the sources is that mining was a low-status occupation, one for enslaved people, criminals and the truly desperate. Being “sent to the mines” is presented, alongside being sent to work in the mills, as a standard terrible punishment for enslaved people who didn’t obey their owners and it is fairly clear in many cases that being sent to the mines was effectively a delayed death sentence. Diodorus Siculus describes mining labor in the gold mines of Egypt this way, in a passage that is fairly representative of the ancient sources on mining labor more generally (3.13.3, trans Oldfather (1935)):

For no leniency or respite of any kind is given to any man who is sick, or maimed, or aged, or in the case of a woman for her weakness, but all without exception are compelled by blows to persevere in their labours, until through ill-treatment they die in the midst of their tortures. Consequently the poor unfortunates believe, because their punishment is so excessively severe, that the future will always be more terrible than the present and therefore look forward to death as more to be desired than life.

It is clear that conditions in Greek and Roman mines were not much better. Examples of chains and fetters – and sometimes human remains still so chained – occur in numerous Greek and Roman mines. Unfortunately our sources are mostly concerned with precious metal mines and those mines also seem to have been the worst sorts of mines to work in, since the long underground shafts and galleries exposed the miners to greater dangers from bad air to mine-collapses. That said, it is hard to imagine working an open-pit iron mine by hand, while perhaps somewhat safer, was any less back-breaking, miserable toil, even if it might have been marginally safer.

Conditions were not always so bad though, particularly for free miners (being paid a wage) who tended to be treated better, especially where their labor was sorely needed. For instance, a set of rules for the Roman mines at Vipasca, Spain provided for contractors to supply various amenities, including public baths maintained year-round. The labor force at Vipasca was clearly free and these amenities seem to have been a concession to the need to make the life of the workers livable in order to get a sufficient number of them in a relatively sparsely populated part of Spain.

The conditions for miners in medieval Europe seems to have been somewhat better. We see mining communities often setting up their own institutions and occasionally even having their own guilds (for instance, there was a coal-workers guild in Liege in the 13th century) or internal regulations. These mining communities, which in large mining operations might become small towns in their own right, seem to have often had some degree of legal privileges when compared to the general rural population (though it should be noted that, as the mines were typically owned by the local lord or state, exemption from taxes was essentially illusory as the lord or king’s cut of the mine’s profits was the taxes). It does seem notable that while conditions in medieval mines were never quite so bad as those in the ancient world, the rapid expansion of mining activity beginning in the 15th century seems to have coincided with a loss of the special status and privileges of earlier medieval European miners and the status associated with the labor declined back down to effectively the bottom of the social spectrum.

(That said, it seems necessary to note that precious metal-mining done by non-free Native American laborers at the order of European colonial states appears to have been every bit as cruel and deadly as mining in the ancient world.)

Bret Devereaux, “Iron, How Did They Make It? Part I, Mining”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-09-18.

May 20, 2023

QotD: Alienation

One of Marx’s most famous concepts, “alienation” initially meant “the systemic separation of a worker from the product of his labor”. The result of a craftsman’s labor is directly visible beneath his hands, growing by the day; when he’s done, the shirt (or whatever) sits there before him, fully finished. The factory worker, by contrast, is little more than a machine-tender; he pulls the lever, and the finished article is squirted out somewhere far down the line, automatically, by machine. His “labor” consists of lever-pulling and jam-clearing.

It was a real enough insight into the psychology of factory work, and Marx deserves all the credit he got for it, but “alienation” was even more useful in a broad social context — the separation of man from the cultural products of his society. After all, if capitalism is the mode of production around which society organizes itself, and the products of capitalism are by definition alienated from their producers, then by extension capitalist society must be alienated from itself. Indeed, what could “society” even mean, in a world of lever-pullers and bearing-lubers and jam-clearers?

Again, a profound and important insight into the social conditions of the Industrial Age. Ours is a mechanical, transactional world, one not well-suited to the kind of organism we are. That’s why Marxism and its spacey little brother Nazism are both what Jeffrey Herf calls “reactionary modernism.” The Communists thought they were the endpoint of the Enlightenment; the Nazis rejected it entirely; but both of them were curdled Romantics, in love with Enlightenment science while terrified of that science’s society. Lenin said that Communism was “Soviet power plus electrification”. Goebbels wasn’t that pithy, but “the feudal system plus autobahns” is pretty much what he meant by Nazism, and both boil down to “medieval peasant villages with air conditioning”.

That the one excludes the other — necessarily, comrade, necessarily, in the full Hegelian sense of the word — never occurred to either of them shouldn’t really be held against them, since both of them were determined to freeze the world exactly as it was. Both were so terrified of individuality that they were determined to stamp it out, not realizing that individuality was the only thing that made their fantasy worlds possible. Medieval peasants who were happy being medieval peasants never would’ve invented air conditioning in the first place, nicht wahr?

Severian, “Alienation”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-10-29.

May 10, 2023

Feasting at a Medieval Tournament

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 9 May 2023

(more…)