It’s been called one of the largest man-made non-nuclear explosions and it destroyed large parts of the City of Halifax, when the SS Mont Blanc ran aground and exploded following a collision in the Narrows between Halifax and Dartmouth with the chartered Belgian Relief ship SS Imo. Nearly two thousand people were killed and thousands more injured in the blast.

A view of the Halifax waterfront shortly after the explosion on the morning of 6 December, 1917

Image via Wikimedia.

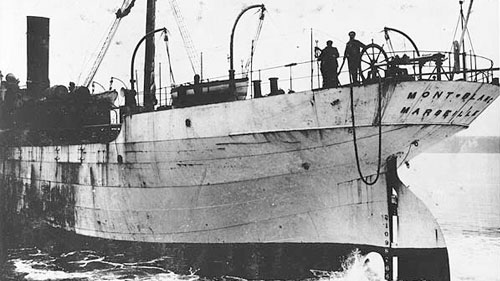

The Mont Blanc was built in 1899 in Middlesbrough, England, and at the time of the explosion was owned by Cie Generale Transatlantique with a St. Nazaire registration. As far as I’m aware there is only one photo of the ship and it shows the stern of the vessel when she was sailing under a Marseilles registration:

Mont Blanc had left New York harbour with a full load of flammable and explosive cargo (including TNT, picric acid, benzol aviation fuel additive, and guncotton) intended for the battlefront in western Europe on the first, and just missed being allowed inside the anti-submarine netting protecting the entrance to the harbour on the evening of the fifth, being forced to wait outside until morning. As soon as the harbour guard allowed passage, the Mont Blanc followed another freighter (believed to be the SS Clara, but identified only as “the green American tramp steamer” in the inquiry) through the barrier and approached the narrows.

As the Mont Blanc made her way up toward the Bedford Basin, the Imo started in the opposite direction headed toward the harbour mouth. The Clara was sailing up the Halifax side of the channel, contrary to harbour rules, so the Imo had to swing over toward the Dartmouth side to avoid the Clara, and then further to the wrong side of the Narrows to avoid the Stella Maris, a tug moving barges around the harbour. In the low visibility, Imo‘s captain and pilot were unaware that another ship was following the Clara so closely and on the correct side of the channel.

According to the accepted “rules of the road”, in this situation the first ship to signal has the right of way and the other ship is expected to defer to the movement of the first ship. Mont Blanc‘s pilot had the ship’s whistle blown once, to indicate their priority, but the Imo replied with two whistles indicating that they did not intend to allow Mont Blanc‘s right of way. At first sighting, the two ships were already within a mile of one another and within the narrowest point of the harbour, which restricted the ability of the Mont Blanc to manouvre. The captain ordered the engines stopped and to steer closer to the Dartmouth side of the channel (with his delicate and explosive cargo, he didn’t want to run the risk of going aground).

Imo was carrying no cargo on this portion of her journey, which meant the propellers were partially out of the water, making the ship much less handy to steer. As the two ships approached, with the ships on approximately parallel courses, the Imo‘s captain ordered the engines to reverse, which caused Imo to swing to starboard (right) and impact the starboard side of the Mont Blanc at 8:45am. The collision did not do fatal structural damage to either ship, but it broke open some of the benzol containers on the deck and the spilled liquid ran down the side of the Mont Blanc, producing a flammable vapour.

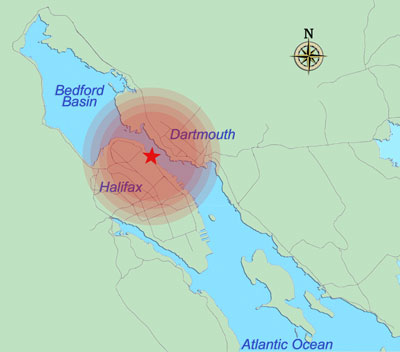

The immediate impact of the explosion covered 325 acres, and windows were broken more than 50 miles away.

Image from http://www.halifaxexplosion.org/explosion2.html

As the Imo‘s engines began to pull the ship back, friction between the two hulls ignited the benzol fumes, which then spread the fire up the hull and onto the foredeck, preventing any effective fire-fighting on the part of the Mont Blanc‘s crew. With no hope of preventing an explosion, the crew abandoned ship and rowed away from the stricken Mont Blanc, which carried on across the channel and eventually ran aground on the Halifax side near Pier 6 at the foot of Richmond Street. At 9:04am, the main cargo exploded, ripping the ship apart and sending chunks of the hull out over the buildings at the waterfront, some landing up to 3.5 miles away from the site of the blast.

This photo was taken two days after the explosion, looking across the Narrows toward the wreck of the SS Imo, aground on the Dartmouth shore.

Image via Wikimedia.

The Wikipedia entry tells of the moment of the explosion:

The ship was completely blown apart and a powerful blast wave radiated away from the explosion at more than 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) per second. Temperatures of 5,000 °C (9,030 °F) and pressures of thousands of atmospheres accompanied the moment of detonation at the centre of the explosion. White-hot shards of iron fell down upon Halifax and Dartmouth. Mont Blanc‘s forward 90 mm gun, its barrel melted away, landed approximately 5.6 kilometres (3.5 mi) north of the explosion site near Albro Lake in Dartmouth, while the shank of her anchor, weighing half a ton, landed 3.2 kilometres (2.0 mi) south at Armdale.

A cloud of white smoke rose to over 3,600 metres (11,800 ft). The shock wave from the blast travelled through the earth at nearly 23 times the speed of sound and was felt as far away as Cape Breton (207 kilometres or 129 miles) and Prince Edward Island (180 kilometres or 110 miles). An area of over 160 hectares (400 acres) was completely destroyed by the explosion, while the harbour floor was momentarily exposed by the volume of water that vaporized. A tsunami was formed by water surging in to fill the void; it rose as high as 18 metres (60 ft) above the high-water mark on the Halifax side of the harbour. Imo was carried onto the shore at Dartmouth by the tsunami. The blast killed all but one on the whaler, everyone on the pinnace and 21 of the 26 men on Stella Maris; she ended up on the Dartmouth shore, severely damaged. The captain’s son, First Mate Walter Brannen, who had been thrown into the hold by the blast, survived, as did four others. All but one of the Mont Blanc crew members survived.

Over 1,600 people were killed instantly and 9,000 were injured, more than 300 of whom later died. Every building within a 2.6-kilometre (1.6 mi) radius, over 12,000 in total, was destroyed or badly damaged. Hundreds of people who had been watching the fire from their homes were blinded when the blast wave shattered the windows in front of them. Stoves and lamps overturned by the force of the blast sparked fires throughout Halifax, particularly in the North End, where entire city blocks were caught up in the inferno, trapping residents inside their houses. Firefighter Billy Wells, who was thrown away from the explosion and had his clothes torn from his body, described the devastation survivors faced: “The sight was awful, with people hanging out of windows dead. Some with their heads missing, and some thrown onto the overhead telegraph wires.” He was the only member of the eight-man crew of the fire engine “Patricia” to survive.

Intercolonial Railway dispatcher Vince Coleman is credited with saving some three hundred passengers of an inbound Saint John train, by going back to the telegraph office and ordering the train to stop outside the likely blast zone: “Hold up the train. Ammunition ship afire in harbor making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Good-bye boys.” The train was only slightly damaged and there were no fatalities onboard. Coleman died at his post when the ship exploded.

The earliest rescue efforts were mounted by the crews of British, Canadian, and American naval ships in port, and two US Navy ships that arrived later in the day. Many wounded were brought aboard the ships and treated there: the explosion having taken down all the electric power lines in the area, these were the best-lighted-and-heated places to take the injured until emergency power lines could be set up onshore.

Later in the day, a small fire near the magazine of Wellington Barracks caused a panic about a second explosion which hampered early rescue attempts adjacent to the blast area. Rescue trains were dispatched from many communities in the Maritimes and New England, including a major relief effort from Boston. A severe winter storm struck Halifax the next day, causing further delays in locating and assisting wounded and injured Haligonians. Sixteen inches of snow blocked several railway lines, and caused greater distress among the survivors, and knocking out the telegraph lines that in many cases had only just been re-connected after the blast.

For further reading on the explosion, the rescue efforts, and the aftermath, I can recommend Laura M. Mac Donald’s Curse of the Narrows, which recounts a great many individual stories of the people of Halifax and Dartmouth who lived through the disaster.

Update, 6 December: Rick Tessner sent me a link to this video which does a good job of explaining what happened to cause the explosion.

Sixty Symbols

Published on Dec 4, 2017Sixty Symbols regular Dr Meghan Gray on an infamous event that occurred in her home town – the Halifax Explosion of December 6, 1917.

MORE DETAILS

Maritime Museum of the Atlantic: https://maritimemuseum.novascotia.ca/…

Nova Scotia archives stuff: https://novascotia.ca/news/smr/2009-1…

CBC: http://newsinteractives.cbc.ca/halifa…While not a typical video for us, Dr Gray is a Sixty Symbols stalwart and really wanted to share the story of this explosion which is an event of great interest to her home town of Halifax — and an event with a pretty significant science component.