Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 24 Apr 2020“The Bard” is not only an essential class in any D&D party, but a byword for England’s most famous writer. We’ve covered a bit of Shakespeare before on OSP — just a bit, really, nothing major, only a dozen — but today we’ll look at how William got to Bard-ing, and how he accidentally became England’s biggest Historian.

SOURCES and Further Reading: The Introduction and play-texts of the Folger Shakespeare Library (The best way to read Shakespeare), “Shakespeare: A Very Short Introduction” by Wells

This video was edited by Sophia Ricciardi AKA “Indigo”. https://www.sophiakricci.com/

Our content is intended for teenage audiences and up.PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/h3AqJPe

MERCH LINKS: https://www.redbubble.com/people/OSPY…

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

April 25, 2020

History-Makers: Shakespeare

November 15, 2019

Shakespeare Summarized: Romeo And Juliet

Overly Sarcastic Productions

27 April 2014Yeah, sorry. I don’t like this play very much. I know it’s a classic, I know it inspired countless other love stories… I… I can’t help it. It’s just too funny. I’m sorry if you actually thought this play was tragic, because I did not respect your opinion here at ALL.

November 8, 2019

Shakespeare Summarized: Macbeth

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 12 April 2014Here it is! The Scottish Play. The bloodiest of the bloody. An epic tale of magic, madness and stabbing. It’s so gory, even Tarantino thinks it’s over the top.

Making it funny was pretty tough.

November 7, 2019

Replacing “dead, white male” writers with contemporary First Nations writers

Barbara Kay, as you would expect is not a fan of this move by this school board in the Windsor area:

Some years ago, the late, great writer George Jonas asked me about my intellectual influences. Who did I remember as especially formative? Oh, George Orwell, of course. I read Animal Farm in my mid-teens, 1984 a little later, and most of his other writings over the course of my salad years. It would be hard to overstate his effect on my understanding of concepts like “freedom,” “power” and “decency.”

Since Orwell has never been “owned” by the right or the left, both admiring his prose as a model for clarity and coherence, he is the one English-language writer I would consider indispensable for any high school literature curriculum.

Up to now, most educators have concurred. But the Windsor, Ont.-area Greater Essex County District School Board has announced that, in accordance with the spirit of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), Orwell and other canon favourites in the Grade 11 literature curriculum, including Shakespeare, will be set aside in favour of a course wholly devoted to Indigenous writing. Eight of the district’s 15 schools have already replaced former standards with such books as Indian Horse, In This Together and Seven Fallen Feathers under the rubric of Understanding Contemporary First Nations, Métis and Inuit Voices.

“This decision wasn’t made lightly,” said Tina DeCastro, a teacher consultant with the school board’s Indigenous Education Team. The decision arose from a motion passed by the school board’s trustees as a response to TRC calls for action. Eastern Cherokee Sandra Muse Isaacs, Professor of Indigenous Literature at the University of Windsor, defends the radical change as necessary on the grounds that Indigenous stories have been ignored in the past. “Our stories predate Canada. It’s as simple as that.”

Is it really that simple?

I don’t think there is a sentient Canadian today who isn’t aware that Indigenous voices have been neglected in the past, and who would not wholeheartedly support the addition of Indigenous writing to contemporary literature curricula. But an entire year devoted to Indigenous literature that supplants revered works by great writers from the civilization that produced Canada as a nation-state, in order to redress the offence of historical inattention to Indigenous people, is to rob the majority of Canadian students of their cultural patrimony.

October 30, 2019

Shakespeare Summarized: Julius Caesar

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 1 Dec 2013Here we go again! It’s only taken me several months…

Sarcastified Shakespeare returns, this time with a look at that historical tragedy we all love to write essays about, Julius Caesar!

I think the real main character here was Brutus’s crippling self-esteem issues…

October 22, 2019

Shakespeare Summarized: Hamlet

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 13 April 2013Well, this one is longer than the last one, but in fairness it’s 2000% shorter than the actual movie.

Continuing the trend, this video summarizes THE TRAGEDIE OF HAMLET PRINCE OF DENMARK, commonly known as Hamlet.

Goodness, he really is a whiner, isn’t he? And he’s supposed to be the sympathetic character!

Note: This is the second version of Hamlet Summarized, because I made the mistake of using a copyrighted song in the last one. Oops.

May 17, 2019

Was Shakespeare really an illiterate illegal immigrant disabled asexual woman of colour?

Oliver Kamm discusses the most recent “Was Shakespeare really …?” article, this one published in The Atlantic by Elizabeth Winkler:

This was long thought to be the only portrait of William Shakespeare that had any claim to have been painted from life, until another possible life portrait, the Cobbe portrait, was revealed in 2009. The portrait is known as the “Chandos portrait” after a previous owner, James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos. It was the first portrait to be acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in 1856. The artist may be by a painter called John Taylor who was an important member of the Painter-Stainers’ Company.

National Portrait Gallery image via Wikimedia Commons.

[Winkler] accuses what she calls orthodox Shakespeare scholars of “a dogmatism of their own” on the issue, whereby “even to dabble in authorship questions is considered a sign of bad faith, a blinkered failure to countenance genius in a glover’s son.” Armed with this tendentious premise, along with the less contentious one that Shakespeare depicts female characters with unrivalled sympathy and insight, Winkler spins a hypothesis that Emilia Bassano, born in London in 1569 to Venetian immigrants, is a viable candidate for the true author.

Even as I read Winkler’s piece, I expected a denouement that it was all a piece of fiction, analogous to the enjoyable 2009 caper St Trinian’s 2: The Legend of Fritton’s Gold, which ends with buried treasure under the Globe Theatre and the discovery of Shakespeare’s true identity. It never came. The article was presented as a serious contribution to a debate in which Winkler has made a potentially historic discovery.

In British newspapers, there is a longstanding technique of obscuring a paucity of evidence in support of a preposterous thesis by posing it as a question. It’s been dubbed by the political commentator John Rentoul “Questions to Which the Answer is No” (QTWAIN). Winkler’s article employs the stratagem liberally. “Was Shakespeare’s name useful camouflage, allowing [Bassano] to publish what she otherwise couldn’t?” “Could Bassano have contributed [to literature] even more widely and directly?” In a moment of self-knowledge, Winkler asks: “Was I getting carried away, reinventing Shakespeare in the image of our age?” Yet she immediately supplies not the correct answer but yet another QTWAIN: “Or was I seeing past gendered assumptions to the woman who — like Shakespeare’s heroines — had fashioned herself a clever disguise?”

Feminist readings of Shakespeare have enriched literary criticism and scholarship in, among other areas, reconsidering genre distinctions and examining the effects of patriarchal structures on relations between the sexes. There is no decorous way of saying that Winkler’s article, by contrast, is a farrago that should never have been conceived, pitched, commissioned or published. Winkler credulously retails a series of purported mysteries about Shakespeare’s authorship that are no mystery at all, and repeats claims derived from Shakespeare denialists that any capable scholar would have been able to correct. She places particular stress on the work of a “meticulous scholar” Diana Price, who claims: “Writers in Elizabethan and Jacobean England left behind records of their professional activities. Shakespeare left behind documentation of his professional activities, but none is literary… He is the only alleged [emphasis added] writer of any consequence from the time period who left behind no personal evidence of his career as a professional writer.”

Price is neither meticulous nor a scholar (she designates herself “an independent scholar,” which should have caused Winkler greater wariness). As Alan Nelson of Berkeley University has put it, Price knows how to put a sentence together but she doesn’t know how to put an argument together.

We in fact have unimpeachable evidence of Shakespeare’s activities as a writer, far more than we do for, say, his fellow-dramatists John Webster or Cyril Tourneur, but by a series of rhetorical sleights-of-hand Price rules it all inadmissible. To give a single but weighty example: Shakespeare’s fellow actors John Heminge and Henry Condell assembled the First Folio of Shakespeare’s works, published in 1623, with Shakespeare’s name on the title page and his engraved image in the frontispiece, and with a laudatory poem by Ben Jonson referring to the author as “Sweet Swan of Avon.” Price dismisses this as evidence of authorship because it’s posthumous, coming seven years after Shakespeare’s death, even though the planning and publishing of the book must have taken years, and Heminge, Condell and Jonson all knew Shakespeare personally. This isn’t scholarship but sophistry.

A noteworthy example of Betteridge’s Law of Headlines. (As is, of course, the headline on this post.)

April 18, 2019

Shakespeare’s work is merely used to highlight the brilliance and originality of modern theatrical directors

Anthony Daniels reports for Quadrant Online of how he recently attended a performance of a play by some unimportant dead English white guy:

The precise date of the discovery by theatre directors that they are greater than Shakespeare cannot be specified: the discovery was more a process than an event. But by the time I saw a production of Richard II at the Almeida Theatre a few weeks ago, the superior genius of any director over that of Shakespeare was an established principle and indisputable fact.

[…]

But if I had an elevated conception of Shakespeare, how naive and mistaken I was! I knew nothing of Richard II — the play, that is, not the king — until I saw the production by Joe Hill-Gibbins. How narrow had been my previous conception of it! I discovered, among other things, that Richard was a short, fat fifty-eight-year-old in a black T-shirt, with a crown of the kind that is awarded to the person who finds the fève in the galette des rois that the French eat on the sixth of January, that the Duke of Norfolk was a woman dressed like a cleaning lady, and that all the action of the play takes place in what looks like a large biscuit tin, without exit or entrance. All this, of course, means something far deeper than anything that a mere Shakespeare could convey, being deeply symbolic, and therefore required real inventive genius on the part of the director to bring forth.

While the same actress took the parts of the Duke of Norfolk, Bushy and Green (all of them looking like cleaning ladies and each indistinguishable from the other because they could not leave the stage even to change costume), and the parts of both the Earl of Northumberland and the Bishop of Carlisle by other actresses, actual women’s roles such as that of Richard’s Queen were expunged entirely from the text. Between them, three actresses played five male parts and only one female. There is a profound lesson in this somewhere, no doubt in enlightened gender fluidity.

Most of the lines were delivered as if they were a religious incantation in a dead language that both the celebrants and the congregation desired to get over with as quickly as possible, clear diction being one of the many tools by which class hegemony is so unjustly exercised. The actor who took the part of Richard, it is true, was comprehensible, but made the acting of Sir Henry Irving appear taciturn by comparison. If emphasis is good, overemphasis must be better: no more stiff upper lip, we are all hysterics now, and can understand nothing that is not accompanied by gesticulation.

The director fortunately realised that Shakespeare got the order of his play wrong: Richard’s great speech in Act V scene 5 (“I have been studying how I may compare / This prison unto the world …”) was actually a prologue. The director is not the interpreter of Shakespeare, but rather Shakespeare is, and ought to be, the occasion, the opportunity, for the director to place his own immortal (and highly original) genius before the world.

April 5, 2019

If Shakespearean Insults Were Used Today – Anglophenia Ep 13

Anglophenia

Published on 24 Sep 2014Siobhan Thompson reacts to everyday office frustrations with some barbs from the Bard. Check out the Shakespeare plays from which the insults originated here: http://www.bbcamerica.com/anglophenia…

January 31, 2018

Don’t mention Macbeth – Blackadder – BBC

BBCWorldwide

Published on 24 May 2010The palace entertains two distinguished and highly superstitious actors. Blackadder is careful not to mention the name of the Scottish play. Funny clip taken from the classic BBC comedy Blackadder.

October 11, 2017

Reading Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

In the latest Libertarian Enterprise, Richard Blake introduces one of the greatest English historians and explains why his work is still well worth reading:

Edward Gibbon (1737-94) was born into an old and moderately wealthy family that had its origins in Kent. Sickly as a child, he was educated at home, and sent while still a boy to Oxford. There, an illegal conversion to Roman Catholicism ruined his prospects of a career in the professions or the City. His father sent him off to Lausanne to be reconverted to the Protestant Faith. He came back an atheist and with the beginnings of what would become a stock of immense erudition. He served part of the Seven Years War in the Hampshire Militia. He sat in the House of Commons through much of the American War. He made no speeches, and invariably supported the Government. He moved for a while in polite society – though his increasing obesity, and the rupture that caused his scrotum to swell to the size of a football, made him an object of mild ridicule. Eventually, he withdrew again to Switzerland, where obesity and his hydrocele were joined by heavy drinking. Scared by the French Revolution, he came back to England in 1794, where he died of blood-poisoning after an operation to drain his scrotum.

When not eating and drinking, and putting on fine clothes, and talking about himself, he found time to become the greatest historian of his age, the greatest historian who ever wrote in English, one of the greatest of all English writers, and perhaps the only modern historian to rank with Herodotus and Thucydides and Tacitus. The first volume of his History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire astonished everyone who knew him. The whole was received as an undisputed classic. The work has never been out of print during the past quarter-millennium. It remains, despite the increase in the number of our sources and our better understanding of them, the best – indeed, the essential – introduction to the history of the Roman Empire between about the death of Marcus Aurelius and the death of Justinian.

I’ve read a few abridged versions of Gibbon’s great work, and I intend to start on the unexpurgated version once I’ve finished the New Cambridge Modern History (I have all in hand except Volume XII, the Companion Volume). This is why Blake considers Gibbon to be such an important and still-relevant writer:

1. Greatness as a Writer and a Liberal

I cannot understand the belief, generally shared these past two centuries, that the golden age of English literature lay in the century before the Civil War. I accept the Prayer Book and the English Bible as works of genius that will be appreciated so long as our language survives. I admire the Essays of Francis Bacon and one or two lyrics. But I do not at all regard Shakespeare as a great writer. His plays are ill-organised, his style barbarous and tiresome. I fail to understand how pieces like A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Romeo and Juliet, with their long, ranting monologues, can be thought equal to the greatest products of the Athenian theatre. I grant that Julius Caesar is a fine play – but only because Shakespeare stayed close to his ancient sources for the plot, and wrote in an uncharacteristically plain style. Perhaps I am undeveloped in some critical faculty; and I know that people whose judgements I trust have thought better of him. But I cannot see Shakespeare as a great writer or his age as the greatest in our literature. […]

2. His Scholarship

As said, this was not my first meeting with Gibbon. I was twelve when I found him in the abridgement by D.M. Low. As an undergraduate, I made use of him in the J.B. Bury edition up till the reign of Heraclius and the Arab conquests. In my middle twenties, I went through him again in a desultory manner, skipping chapters that did not interest me. But it was only as I approached thirty that I read him in the full and proper order, from the military resources of the Antonines to the revival of Rome under the Renaissance Popes. It is only by reading him in the whole, and by paying equal attention to text and footnotes, that he can be appreciated as a supreme historian. […]

3. His Fairness as an Historian

Even where he can be criticised for letting his prejudices cloud his judgement, Gibbon remains ultimately fair. He dislikes Christianity, and is convinced that it contributed to the decline of the Empire. His fifteenth and sixteenth chapters are one long sneer at the rise and progress of the Christian Faith. They excited a long and bitter controversy. There was talk for a while of a prosecution for blasphemy. But this was only talk. A man of Gibbon’s place in the social order was not to be taken into court like some hack writer with no connections.

August 4, 2017

QotD: Shakespeare’s sonnets

The Sonnets were published late in Shakespeare’s career (1609) — by a clever and unscrupulous man. His name was Thomas Thorpe. He ran what was for the times a unique publishing business, playing games with “copyright” that were often unconscionable but, usually, this side of the law. He owned neither a printing press, nor a bookstall — two things that defined contemporary booksellers — subcontracting everything in his slippery way. Indeed, I would go beyond other observers, and describe him as a blackguard; and I think Will Shakespeare would agree with me. Though Shakespeare would add, “A witty and diverting blackguard.”

He collected these sonnets, quite certainly by Shakespeare, but written at much different times and for quite various occasions, from whatever well-oiled sources. Thorpe had a fine poetic ear, and knew what he was doing. He arranged the collection he’d amassed in the sequence we have inherited — 154 sonnets that seem to read consecutively, with “A Lover’s Complaint” tacked on as their envoi — then sold them as if this had been the author’s intention.

We have sonnets not later than 1591, interspersed with others 1607 or later. In one case (Sonnet 145), we have what I think is a love poem Shakespeare wrote about age eighteen, to a girl he was wooing: one Anne Hathaway. (She was twenty-seven.) It is crawling with puns, for instance on her name, and stylistically naïve, but has been placed within the “Dark Lady” sonnets (127 to 152) in a mildly plausible way. It hardly belongs there.

Indeed, once one sees this it becomes apparent, surveying the whole course, that there is rather more than one “Dark Lady” in the Sonnets, and that like most red-blooded men, our Will noticed quite a number of interesting women over his years. But Thorpe has folded them all into one for dramatic effect.

David Warren, “Dark gentleman of the Sonnets”, Essays in Idleness, 2015-05-11.

July 30, 2017

QotD: Orwell on climate change since Shakespeare’s day

To the lovers of useless knowledge (and I know there are a lot of them, from the number of letters I always get when I raise any question of this kind) I present a curious little problem arising out of the recent Pelican, Shakespeare’s England. A writer named Fynes Morrison, touring England in 1607, describes melons as growing freely. Andrew Marvell, in a very well-known poem written about fifty years later, also refers to melons. Both references make it appear that the melons grew in the open, and indeed they must have done so if they grew at all. The hot-bed was a recent invention in 1600, and glass-houses, if they existed, must have been a very great rarity. I imagine it would be quite impossible to grow a melon in the open in England nowadays. They are hard enough to grow under glass, whence their price. Fynes Morrison also speaks of grapes growing in large enough quantities to make wine. Is it possible that our climate has changed radically in the last three hundred years? Or was the so-called melon actually a pumpkin?

George Orwell, “As I Please”, Tribune, 1944-11-03.

April 7, 2017

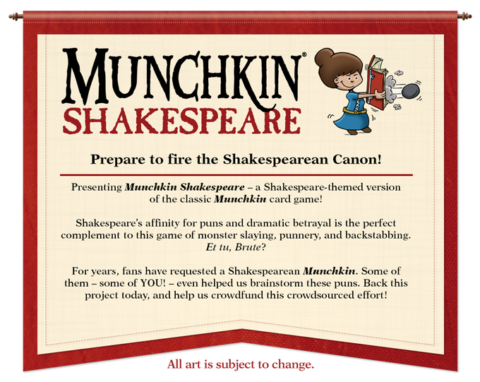

The art of Shakespeare … well, actually the art of Munchkin Shakespeare

John Kovalic reflects on the now-complete artwork for Munchkin Shakespeare:

Munchkin Shakespeare is DONE!

At least my part.

Final tally: about 250 cards, bookmarks, covers, etc.

It was, without question, the largest single Munchkin project I’ve ever tackled at one sitting.

Well, several sittings, really. Over about a two-month period.

The final sitting was the best, though. In London at the time, I wandered around Southwark – Shake-dawg’s stomping grounds – and chose the bar at Shakespeare’s Globe to finish the last few drawings.

[…]

Munchkin Shakespeare was a hugely fun project – but it was also hugely huge, thanks to you monsters and all the stretch-goals you hit.

Would more time have been helpful? Yes. But then, that’s always the case. Point being, Munchkin Shakespeare is going to look fantastic. Most of that is due to the Steve Jackson Games Art Department, which always manages to make my silly little scribblings look great. Those folks are amazing.

Also? The cards are hilarious. I mean, truly madcap, green-eyed, bloodstained tremendous. Thanks to Steve Jackson, Andrew Hackard, and many contributors who threw in crazy ideas during a crowdsourcing braintrust info-dump that launched this too, too silly project.

Here are some first-looks at a few of the cards (Insert usual “Art Not Final” etc. things I’m supposed to say here)!

April 5, 2017

QotD: Sir John Falstaff

… in the back of my mind always ran the great anti-perfectionist utterance of Sir John Falstaff, Shakespeare’s indelible comic character, in Part 1 of Henry IV: “Banish plump Jack, and banish all the world.” A world of perfect sense and good behavior would be well-nigh intolerable: we need Falstaffs, even if we are not Falstaffian ourselves.

If we were to describe a man as deceitful, drunken, cowardly, dishonest, boastful, unscrupulous, gluttonous, vainglorious, lazy, avaricious, and selfish, we should hardly leave room in him for good qualities. No one would take it as a compliment to be described in this way, and we would avoid a person described in such a fashion. Falstaff was all those things, but probably no character in all literature is better loved. Only Don Quixote can compete; and our love of Falstaff is not despite his roguery but because of it. Certainly we would rather spend an evening in his company than with the totally upright Lord Chief Justice of Part 2 of Henry IV. A world of such rectitude, in which everyone had the justice’s probity, would be better, no doubt: but it would not be much fun.

But there is everything in the fat old knight to repel us also: he is almost certainly dirty, and, as a doctor, I would not have looked forward to performing a physical examination on him. He is so fat that the slightest physical effort causes him to exude greasy sweat. As Prince Hal says, he “lards the lean earth as he walks along.” To enjoy Falstaff, you have to be in a tavern; but the world, for most people, cannot be a giant tavern, and outside that setting, Falstaff is distinctly less amusing.

[…]

When Falstaff toward the end of Part 2 of Henry IV learns from Pistol that the old king is dead and that Prince Hal has succeeded him, he immediately sees his opportunity for the unmerited advancement not only of himself but of his cronies. He knows the worthlessness of the rural magistrate, Robert Shallow, and of the ensign, Pistol, only too well; yet he says: “Master Robert Shallow, choose what office thou wilt in the land, ’tis thine. Pistol, I will double charge thee with dignities.” He gives not a moment’s thought—he is temperamentally incapable of doing so—to the consequences of treating public office as a means only of living perpetually at other people’s expense.

Again, when given the task of raising foot soldiers, Falstaff has no compunction in selling exemptions from service and appropriating to himself the money for arms and equipment, leaving his soldiers ill prepared for the battle and with, as he says, “not a shirt and a half” between them: “I have led my ragamuffins where they are peppered [with shot]. There’s not three of my hundred and fifty left alive.” Falstaff sheds not even a crocodile tear for his lost men; their fate simply does not interest him, once they have served his turn and he has made his profit from having recruited them. Even Doctor Johnson is too indulgent when he says: “It must be observed that he is stained with no enormous or sanguinary crimes, so that his licentiousness is not so offensive but that it may be borne for his mirth.” True, he is not sanguinary as a sadist is sanguinary; but depriving 150 men of the means to fight before a battle that ends in their deaths is no mere peccadillo, either.

Why, then, do we forgive and even still love him? If he had been thin, we might have been much less accommodating of his undoubted vices (Hazlitt, in his essay on Falstaff, emphasized the importance of his fatness). At a time when to be a “stuffed cloak-bag of guts,” as Prince Hal calls him, was unusual and most men were, of necessity, thin, Falstaff’s immense size was a metonym for jollity and good cheer — as fatness still is with Santa Claus. It would not have made sense for Julius Caesar, after noting that “Yon Cassius has a lean and hungry look,” to say that such men are well contented. And had Falstaff been slender, he would not have been what Johnson called him, “the prince of perpetual gaiety.”

Falstaff appeals to us because he holds up a distorting mirror to our weaknesses and makes us laugh at them. Falstaff’s dream is that of half of humanity: of luxurious ease and continual pleasure, untroubled by the necessity to work or to do those things that he would rather not do (Falstaff will do anything for money except work for it). There is luxury in time as well as in material possessions, and no figure lives in greater temporal luxury than Falstaff, to whom the concept of punctuality or a timetable would be anathema. Former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi was — or rather, appeared to be — a kind of Falstaff figure, admired by many, though eventually detested by even more, who seemed to lead an effortless life of merrymaking and who was unafraid of the world’s censure. He was therefore able to say heartless but witty things that the rest of us, cowed by the moral disapproval of others, laughed at under our breaths but would not dare to say ourselves.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Why We Love Falstaff: There is some of Shakespeare’s incorrigible rogue in all of us”, City Journal, 2015-08-16.