Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 20 Mar 2020This book is:

10% Mike

20% stars

15% concentrated power of mars

5% water

50% cult

and 100% topics that are very adultThis video was requested by our longtime patron Joshua A. Demic!

Can you use the “product of the times” defense if the book was wildly controversial for its time? Asking for a comment section…

Our content is intended for teenage audiences and up. No, seriously. We REALLY MEAN IT.

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

MERCH LINKS: https://www.redbubble.com/people/OSPY…

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

Discord: https://discord.gg/h3AqJPe

March 21, 2020

Modern Classics Summarized: Stranger In A Strange Land

October 11, 2019

QotD: Religious hysteria

As for […] the idea that we could lose our freedom by succumbing to a wave of religious hysteria, I am sorry to say that I consider it possible. I hope that it is not probable. But there is a latent deep strain of religious fanaticism in this, our culture; it is rooted in our history and it has broken out many times in the past.

It is with us now; there has been a sharp rise in strongly evangelical sects in this country in recent years, some of which hold beliefs theocratic in the extreme, anti-intellectual, anti-scientific, and anti-libertarian.

It is a truism that almost any sect, cult, or religion will legislate its creed into law if it acquires the political power to do so, and will follow it by suppressing opposition, subverting all education to seize early the minds of the young, and by killing, locking up, or driving underground all heretics. This is equally true whether the faith is Communism or Holy-Rollerism; indeed it is the bounden duty of the faithful to do so. The custodians of the True Faith cannot logically admit tolerance of heresy to be a virtue.

Nevertheless this business of legislating religious beliefs into law has never been more than sporadically successful in this country — Sunday closing laws here and there, birth control legislation in spots, the Prohibition experiment, temporary enclaves of theocracy such as Voliva’s Zion, Smith’s Nauvoo, and a few others. The country is split up into such a variety of faiths and sects that a degree of uneasy tolerance now exists from expedient compromise; the minorities constitute a majority of opposition against each other.

Could it be otherwise here? Could any one sect obtain a working majority at the polls and take over the country? Perhaps not — but a combination of a dynamic evangelist, television, enough money, and modern techniques of advertising and propaganda might make Billy Sunday’s efforts look like a corner store compared to Sears Roebuck.

Throw in a Depression for good measure, promise a material heaven here on earth, add a dash of anti-Semitism, anti-Catholicism, anti-Negrosim, and a good large dose of anti-“furriners” in general and anti-intellectuals here at home, and the result might be something quite frightening — particularly when one recalls that our voting system is such that a minority distributed as pluralities in enough states can constitute a working majority in Washington.

Robert A. Heinlein, “Concerning Stories Never Written”, Revolt in 2100, 1953.

October 4, 2019

QotD: Freedom of thought

For the first time in my life, I was reading things which had not been approved by the Prophet’s censors, and the impact on my mind was devastating. Sometimes I would glance over my shoulder to see who was watching me, frightened in spite of myself. I began to sense faintly that secrecy is the keystone of all tyranny. Not force, but secrecy … censorship. When any government, or any church for that matter, undertakes to say to its subjects, This you may not read, this you must not see, this you are forbidden to know, the end result is tyranny and oppression, no matter how holy the motives. Mighty little force is needed to control a man whose mind has been hoodwinked, contrariwise, no amount of force can control a free man, a man whose mind is free. No, not the rack, not fission bombs, not anything — you can’t conquer a free man; the most you can do is kill him.

Robert A. Heinlein, “If This Goes On —”, 1940.

June 19, 2019

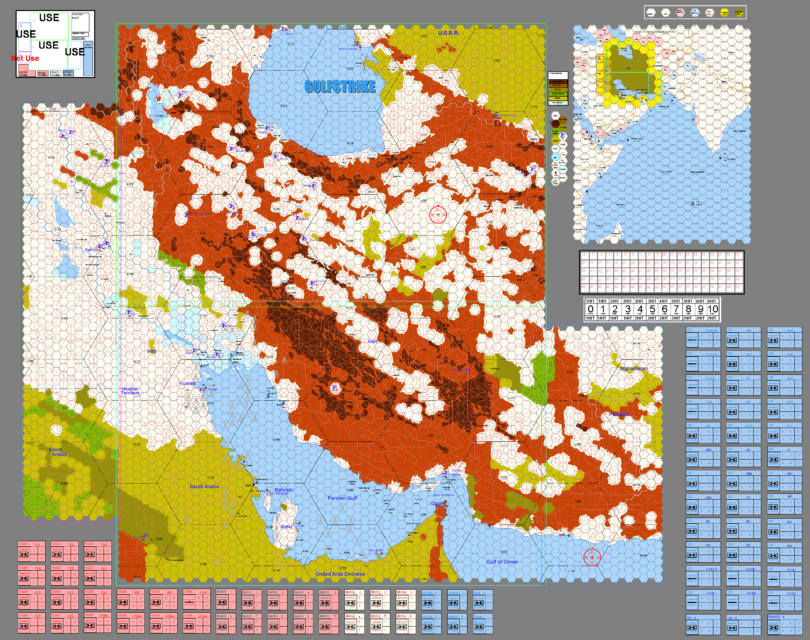

Avoiding a hot war with Iran

Jay Currie responds to a recent article at ZeroHedge, on the US-Iran situation:

The game map for Gulf Strike, an early 1980s board wargame by Victory Games.

Image from https://pbem.brainiac.com/vg.htm

The article outlines all the ways that this approach to war with Iran would be folly and while I don’t necessarily agree with all the points made, the general point that massive force however strategically deployed will almost certainly produce results that the US and the rest of the world will not like one little bit. While you can bomb the Hell out of Iran, Iran has a number of retaliatory options ranging from the possibility of an EMP hit (they may have a rudimentary nuke) to closing the Strait of Hormuz to using Hezbollah sleeper cells in the US to hit critical infrastructure. While I have no doubt the US could beat Iran in a straight war, it would be long, bloody, politically suicidal for Trump and nasty for ordinary Americans.

Worse, it would be a strategic error. If the US leaves its current sanctions in place the Iranian economy will grind to something of a halt. Support for the current Iranian regime, already shakey, will decline. Yes, the current regime will continue with its provocations – I have no doubt it was Iranians who put holes in the sides of two tankers. But, so what?

Exciting as a hot war with Iran would be for assorted policy wonks, it would be an expensive exercise in futility compared to a longer term cold war with some clever extras.

First off, the Americans should make it very clear to the Iranians and the world that while they are committed to freedom of navigation, they are not interested in massive responses to minor incidents. If there is to be any response at all to the tanker mines (if that is what they were) it should be very local indeed. Find the boat in the video and sink it (or one very much like it – no need to be too picky).

Second, using US cyber assets – such as they are – it is time to see just how effectively infrastructure can be disrupted rather than destroyed. A sense of humour would be a huge asset here. Being able to cut into TV broadcasts is one thing, telling jokes at the Ayatollah’s expense is another.

Third, the Israelis did a very good business in the selective assasination of Iran’s nuclear scientists. A similar tactic against Iranian civil and military officials engaged in terrorism or attacks on shipping would be throughly demoralizing for the Iranian regime.

On point two, I’m reminded of a key scene in Robert Heinlein’s “If This Goes On—” (later published in expanded form in Revolt in 2100), where the United States has fallen under the control of religious fanatics (vaguely Christian, but carefully not identified with any then-current sect) so that “The Prophet” occupies the role of head of state and unquestioned all-powerful religious leader. The current Prophet performs a televised annual “miracle” where he is seen on-camera to transform into Nehemiah Scudder, the First Prophet, and give blessings and advice to the current Prophet and to the American people. The conspirators manage to take over the central TV feed and replace the “genuine” Prophet’s message with a skilled actor’s portrayal of Scudder calling America to arms to overthrow the false Prophet. This is the start of the armed rebellion against the Prophet. In the technology of the story, this required a strike team to attack and occupy the physical studio where the broadcast originated — literally a suicide mission. In our digital world, the “strike team” might never need to leave Fort Meade (or wherever the data centre might be)…

June 10, 2019

QotD: Robert Heinlein on “honest work”

The beginning of 1939 found me flat broke following a disastrous political campaign (I ran a strong second best, but in politics there are no prizes for place or show).

I was highly skilled in ordnance, gunnery, and fire control for Naval vessels, a skill for which there was no demand ashore — and I had a piece of paper from the Secretary of the Navy telling me that I was a waste of space — “totally and permanently disabled” was the phraseology. I “owned” a heavily-mortgaged house.

About then Thrilling Wonder Stories ran a house ad reading (more or less):

GIANT PRIZE CONTEST —

Amateur Writers!!!!!!

First Prize $50 Fifty Dollars $50In 1939 one could fill three station wagons with fifty dollars worth of groceries.

Today I can pick up fifty dollars in groceries unassisted — perhaps I’ve grown stronger.

So I wrote the story “Life-Line.” It took me four days — I am a slow typist. I did not send it to Thrilling Wonder; I sent it to Astounding, figuring they would not be so swamped with amateur short stories.

Astounding bought it… for $70, or $20 more than that “Grand Prize” — and there was never a chance that I would ever again look for honest work.

(“Honest work” — an euphemism for underpaid bodily exertion, done standing up or on your knees, often in bad weather or other nasty circumstances, and frequently involving shovels, picks, hoes, assembly lines, tractors, and unsympathetic supervisors. It has never appealed to me. Sitting at a typewriter in a nice warm room, with no boss, cannot possibly be described as “honest work.”)

Robert A. Heinlein, 1980.

August 28, 2018

Stross in conversation with Heinlein

Charles Stross explains why so many Baby Boomer SF writers fall so far short when they write in imitation of Robert Heinlein:

RAH was, for better or worse, one of the dominant figures of American SF between roughly 1945 and 1990 (he died in 1988 but the publishing pipeline drips very slowly). During his extended career (he first began publishing short fiction in the mid-1930s) he moved through a number of distinct phases. One that’s particularly notable is the period from 1946 onwards when, with Scribners, he began publishing what today would be categorized as middle-grade SF novels (but were then more specifically boys adventure stories or childrens fiction): books such as Rocket Ship Galileo, Space Cadet, Red Planet, and Have Space Suit, Will Travel. There were in all roughly a dozen of these books published from 1947 to 1958, and as critic John Clute notes, they included some of the very best juvenile SF ever written (certainly at that point), and were free of many of the flaws that affected Heinlein’s later works — they maintained a strong narrative drive, were relatively free from his tendency to lecture the reader (which could become overwhelming in his later adult novels), and were well-structured as stories.

But most importantly, these were the go-to reading matter for the baby boom generation, kids born from 1945 onwards. It used to be said, somewhat snidely, that “the golden age of SF is 12”; if you were an American boy (or girl) born in 1945 you’d have turned 12 in 1957, just in time to read Time for the Stars or Citizen of the Galaxy. And you might well have begun publishing your own SF novels in the mid-1970s — if your name was Spider Robinson, or John Varley, or Gregory Benford, for example.

Then a disturbing pattern begins to show up.

The pattern: a white male author, born in the Boomer generation (1945-1964), with some or all of the P7 traits (Pale Patriarchal Protestant Plutocratic Penis-People of Power) returns to the reading of their childhood and decides that what the Youth of Today need is more of the same. Only Famous Dead Guy is Dead and no longer around to write more of the good stuff. Whereupon they endeavour to copy Famous Dead Guy’s methods but pay rather less attention to Famous Dead Guy’s twisty mind-set. The result (and the cause of James’s sinking feeling) is frequently an unironic pastiche that propagandizes an inherently conservative perception of Heinlein’s value-set.

It should be noted that Charles Stross is politically left, so calling something “conservative” is intended to be understood as a pejorative connotation, not merely descriptive.

But here’s the thing: as often as not, when you pick up a Heinlein tribute novel by a male boomer author, you’re getting a classic example of the second artist effect.

Heinlein, when he wasn’t cranking out 50K word short tie-in novels for the Boy Scouts of America, was actually trying to write about topics for which he (as a straight white male Californian who grew up from 1907-1930) had no developed vocabulary because such things simply weren’t talked about in Polite Society.

Unlike most of his peers, he at least tried to look outside the box he grew up in. (A naturist and member of the Free Love movement in the 1920s, he hung out with Thelemites back when they were beyond the pale, and was considered too politically subversive to be called up for active duty in the US Navy during WW2.) But when he tried to look too far outside his zone of enculturation, Heinlein often got things horribly wrong. Writing before second-wave feminism (never mind third- or fourth-), he ended up producing Podkayne of Mars.

Trying to examine the systemic racism of mid-20th century US society without being plugged into the internal dialog of the civil rights movement resulted in the execrable Farnham’s Freehold. But at least he was trying to engage, unlike many of his contemporaries (the cohort of authors fostered by John W. Campbell, SF editor extraordinaire and all-around horrible bigot). And sometimes he nailed his targets: The Moon is a Harsh Mistress as an attack on colonialism, for example (alas, it has mostly been claimed by the libertarian right), Starship Troopers with its slyly embedded messages that racial integration is the future and women are allowed to be starship captains (think how subversive this was in the mid-to-late 1950s when he was writing it).

In contrast, Heinlein’s boomer fans rarely seemed to notice that Heinlein was all about the inadmissible thought experiment, so their homages frequently came out as flat whitebread 1950s adventure yarns with blunt edges and not even the remotest whiff of edgy introspection, of consideration of the possibility that in the future things might be different (even if Heinlein’s version of diversity ultimately faltered and fell short).

August 15, 2018

Robert Heinlein – Highs and Lows – #2

Extra Credits

Published on 14 Aug 2018Heinlein’s novels made science fiction mainstream and even contributed to modern libertarianism. His novels vary widely in the philosophies they explore, but ultimately they all reflect how Heinlein saw himself: as the self-reliant “competent man” protagonist of his stories, despite glaring inconsistencies.

August 9, 2018

Robert Heinlein – Rise – Extra Sci Fi – #1

Extra Credits

Published on 7 Aug 2018Before we delve into Robert Heinlein’s famous works, let’s look at an overview of his writing career and the philosophical ideals he was known for: particularly his libertarian worldview, although even this is still hotly debated.

August 2, 2018

Books on the ISS

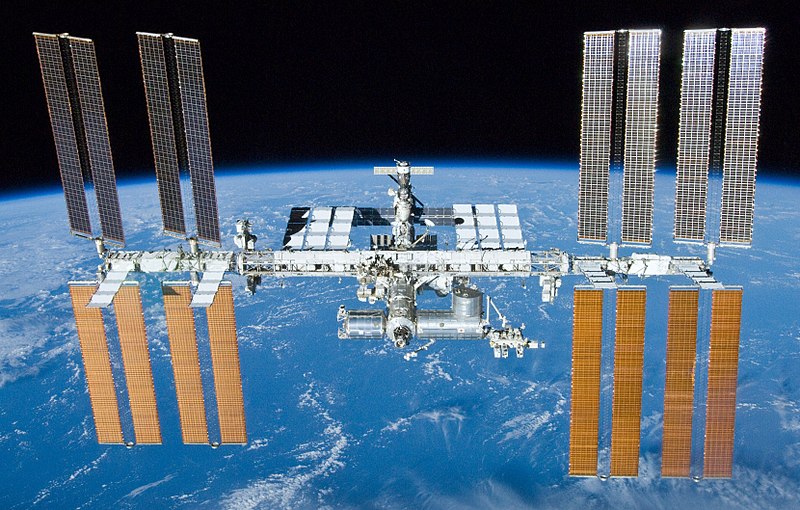

No, that’s not books about the International Space Station, but physical books on the ISS:

The International Space Station is featured in this image photographed by an STS-132 crew member on board the Space Shuttle Atlantis after the station and shuttle began their post-undocking relative separation. Undocking of the two spacecraft occurred at 10:22 CDT on 23 May 2010, ending a seven-day stay that saw the addition of a new station module, Rassvet, replacement of batteries and resupply of the orbiting outpost.

Via Wikimedia Commons

The astronauts on the International Space Station are obviously busy people, but even busy people need some time to relax and unwind. In addition to a well-stocked film library (particularly strong on movies with a space theme, including 2001: A Space Odyssey and Gravity), there are also plenty of books in their informal library.

Some are brought up by the astronauts – Susan Helms was allowed ten paperbacks and chose Gone With the Wind, Vanity Fair and War and Peace in her carryon. Others come with space tourists such as billionaire businessman Charles Simonyi, who brought Faust and Robert Heinlein’s The Moon is a Harsh Mistress.

Authors whose works appear several times in the list include Daniel J. Boorstin (3 books), Terry Brooks (5), Lois McMaster Bujold (11), John Le Carré (3), and David Weber (13).

July 11, 2018

The Golden Age of Science Fiction – Modernity Begins – Extra Sci Fi

Extra Credits

Published on 10 Jul 2018The golden age of science fiction represents a very flawed but fascinating American view of the future; authors Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, and Robert Heinlein were all influential to this time period.

February 13, 2018

Elon Musk as Heinlein’s Delos D. Harriman – “Selling the moon is just what Musk is doing”

I suspect I’d recognize a lot of the books in Colby Cosh‘s collection, as we’re both clearly Robert Heinlein fans. In a column yesterday, he pointed out the strong parallels between Heinlein’s fictional “Man Who Sold the Moon” and his closest counterpart in our timeline, Elon Musk:

Written between 1939 and 1950 for quickie publication in pulp magazines, the Future History is a series of snapshots of what is now an alternate human future — one that features atomic energy, solar system imperialism, and the first steps to deep space, all within a Spenglerian choreography of social progress and occasional resurgent barbarity. It stands with Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy as a monument of golden-age science fiction.

[…]

The result, in the key story of the Future History, is an uncannily accurate description of the design and launch of a Saturn V rocket. (Written before 1950, remember.) But because Heinlein happened not to be interested in electronic computers, all the spacefaring in his books is done with the aid of slide rules or Marchant-style mechanical calculators (which, in non-Heinlein history, had to become obsolete before humans could go to Luna at all). Heinlein sends people to colonize the moon, but nobody there has internet, or is conscious of its absence.

Given that his ideas about computers were from the pre-computer era and even the head of IBM thought there’d be a worldwide demand for a very small number of his company’s devices, that’s not surprising at all. In one of his best novels, a single computer runs almost all of the life support, heat, light, transportation and communication systems on Luna … and is self-aware, but lonely. In later works where computers appear, they tend to be individual personalities or even minor characters, but they’re anything but ubiquitous: powerful, but rare.

I suspect the lack of an internet-equivalent derives both from the nature of his conception of how computing would progress and a form of the Star Trek transporter problem – it solves too many plot issues that could otherwise be usefully woven into stories.

The “key story” I just mentioned is called “The Man Who Sold The Moon.” And if you’re one of the people who has been polarized by the promotional legerdemain of Elon Musk — whether you have been antagonized into loathing him, or lured into his explorer-hero cult — you probably need to make a special point of reading that story.

The shock of recognition will, I promise, flip your lid. The story is, inarguably, Musk’s playbook. Its protagonist, the idealistic business tycoon D.D. Harriman, is what Musk sees when he looks in the mirror.

“The Man Who Sold The Moon” is the story of how Harriman makes the first moon landing happen. Engineers and astronauts are present as peripheral characters, but it is a business romance. Harriman is a sophisticated sort of “Mary Sue” — an older chap whose backstory encompasses the youthful interests of the creators of classic pulp science fiction, but who is given a great fortune, built on terrestrial transport and housing, for the purposes of the story.

January 24, 2018

Charles Stross on Heinlein’s “Crazy Years” notion

Heinlein called it, back in the 1940s, and Charles Stross provides a few more data points to prove he was quite right:

Many, many years ago, in the introduction to my first short story collection, I kvetched about how science fictional futures obsolesce, and the futures we expect look quaint and dated by the time the reality rolls round.

Around the time I published “Toast” (the title an ironic reference to the way near-future SF gets burned by reality) I was writing the stories that later became Accelerando. I hadn’t really mastered the full repertoire of fiction techniques at that point (arguably, I still haven’t: I’ll stop learning when I die), but I played to my strengths — and one technique that suited me well back then was to take a fire-hose of ideas and spray them at the reader until they drowned. Nothing gives you a sense of an immersive future like having the entire world dumped on your head simultaneously, after all.

Now we are living in 2018, round the time I envisaged “Lobsters” taking place when I was writing that novelette, and the joke’s on me: reality is outstripping my own ability to keep coming up with insane shit to provide texture to my fiction.

Just in the past 24 hours, the breaking news from Saudi Arabia is that twelve camels have been disqualified from a beauty pageant because their handlers used Botox to make them more handsome. (The street finds its uses for tech, including medicine, but come on, camel beauty pageant botox should not be a viable Google search term in any plausible time line.) Meanwhile, home in Edinburgh, eight vehicles have been discovered trapped in an abandoned robot car park during demolition work. This is pure J. G. Ballard/William Gibson mashup territory, and it’s about half a kilometre from my front door. The world’s top 1% earned 82% of all wealth generated in 2017 — I’m fairly sure this wasn’t what Adam Smith had in mind — and South Korea has such a high suicide rate that the government intends to make organising a suicide pact a criminal offence.

Go home, 2018, you’re drunk. (Or, as Robert Heinlein might have put it: these are the crazy years, and they’re not over yet.)

September 4, 2017

QotD: Even a world of perfect abundance would not be a crime-free world

So, when I woke up this morning I woke up thinking of how time is different in different parts of the world, which is what the people (Heinlein and Simak included) who pushed for the UN and thought it was the way of the future didn’t seem to get (to be fair, in Tramp Royale it becomes obvious Heinlein got it when he traveled there, and realized it was impossible to bring such a disparate world under one government.)

A minor side note, while listening to City, there is a point at which Simak describes what he might or might not have realized was Marx’s concept of “perfect communism” where the state withers away because there’s no need for it.

Simak thought this would be brought about by perfect abundance. There are no crimes of property when everyone has too much. There are no crimes of violence either, because he seems to think those come from property. (Hits head gently on desk.)

This must have seemed profound to me when I first read the book at 12, but right now I just stared at the mp3 player thinking “what about people who capture other people as sex slaves?” “What about people who covet something someone else made, including the life someone made for themselves? Just because everyone has too much, it doesn’t mean that they don’t covet what someone else made of their too much.”

Which is why I’m not a believer in either Communism or for that matter big L Libertarianism. I don’t believe that humans are only a sum of their material needs and crime the result of the unequal distribution of property. (There is also the unequal distribution of talent, or simply the unequal distribution of happiness, all of which can lead to crime — after all Cain didn’t off Abel because he was starving.) And I don’t believe humans are ever going to become so perfect we can get away with no government, because humans will always (being at heart social apes) lust for power, recognition and heck simply control over others (which is subtly different from power.) So we’re stuck with our good servant but bad master.

Sarah A. Hoyt, “Time Zones”, According to Hoyt, 2015-06-23.

August 24, 2017

Heinlein’s “Crazy Years”

In his recent USA Today column, Glenn “Instapundit” Reynolds gives a shout-out to Robert A. Heinlein’s pre-WW2-era “Future History” timeline which included a segment presciently called “The Crazy Years”:

Very early in his writing career, about 1940, science fiction writer Robert Heinlein outlined a “future history” around which much of his writing would revolve, extending from the mid-twentieth century to the 24th century. Much of what he outlined hasn’t come to pass, but he nailed it in one respect: We live in the “Crazy Years.”

The Crazy Years, in Heinlein’s timeline, were when rapid changes in technology, together with the disruption those changes caused in mores and economics, caused society to, well, go crazy. They ran from the last couple of decades of the 20th Century into the first couple of decades of the 21st. In some of his novels set in that era — Time Enough for Love, for example — he includes random assortments of headlines that may have seemed crazy enough back then, but that seem downright tame today.

I’m not the first to make this connection — science fiction writers John C. Wright and Sarah Hoyt have remarked on it, and as Hoyt notes, “these are the Crazy Years” has become something of a stock joke among Heinlein fans.

But what does that mean? As Wright observes — invoking not only Heinlein but his contemporary A.E. Van Vogt, “craziness” comes when beliefs don’t match facts:

“Craziness can be measured by maladaptive behavior. The behavior the society uses to solve one kind of problem, when applied to an incorrect category, disorients it. When this happens the whole society, even if some members are aware of the disorientation, cannot reach the correct conclusion, or react in a fashion that preserves society from harm. As if society were a dolphin that called itself a fish: when it suffered the sensation of drowning, it would dive. But a dolphin is a mammal, a member of a different category of being. When dolphins are low on air, they surface, rather than dive. Putting yourself in the wrong category leads to the wrong behavior.”

May 16, 2017

QotD: Politics as an auto-immune condition

From living with eczema, which is a chronic auto-immune disorder, I can tell you that it much resembles the way we stumbled through from the forties (perhaps earlier. But in the forties, Heinlein described the communists taking over the Democratic party. And considering it took him till the eighties to vote Republican for the first time, I don’t think he can be considered a biased source.) through to 2001 like I live – most of the time – with my eczema: it flares up in a specific part of my body, and it itches like heck, which of course means that I don’t give my full attention to anything much, but because I’ve lived like this since I was one, it doesn’t really bother me or I should say – I don’t know what it’s like when it’s not bothering me.

[…]

For those who’ve been following our politics in puzzled wonder, it might help if you think of our issues as an autoimmune disorder. Let’s for the moment forget where it came from. Most autoimmune disorders are a bit of a mystery. Yes, part of it was the same bad philosophy that affected Europe at the time, and some of it might have been Soviet agitprop leaking over the ocean (as someone who grew up in Europe and in a fractured country, I know most Americans ignore the chances of that.) Part of it was a predisposition to it. The US and the ancient Israelites are the only people I know of formed on a set of principles and engage in detailed criticism of themselves over their principles. (Most other nations engaged in a criticism of OTHER countries over their own principles and blame OTHER countries for their own failures. For further study, I recommend Europe.)

Anyway, mostly we’ve been living with it and ignoring it, like I do with eczema. The areas where it was chronic: college campuses, “intellectual” areas were relatively minor. Even when it affected Hollywood, as long as it wasn’t flaring up too badly, most people rolled their eyes and ignored it.

[…]

The problem is this – the flare up continued growing. All through the sixties and the seventies, and the eighties, and yes, of course, the nineties, the flare up of self-hatred grew. And just like the eczema in my hands, it started affecting areas we can’t live without: K-12 schools, business, news.

And it’s not just a little. The news have been biased left for a long time (yes, I know the left thinks they’re biased right, but that’s because the left is to the left of Stalin, while the media are basically propping up a state-capitalism system much like China’s.) If you consider Fascism right, then you’re darn tooting the media is biased right. Since I consider it a misnomer, well…

But more importantly, unlike the manifestations of totalitarian impulse in other countries – Russia, Cuba, China – the autoimmune problems are NOT affecting just our governance or our industry. It’s not a matter of destroying our industry so we’ll all be poor. That would be bad enough. The problem is far worse, though: the problem is that the statist ideology now in control of our government, our media, our education and what passes for “high culture” doesn’t just hate this or that part of us. No, they’ve been told/convinced/brainwashed that what’s wrong with the world is US – that the country and its existence ARE the enemy.

It might be the first time in history where in a non-occupied country flying the flag is an act of daring that in certain neighborhoods can get you shunned by all your neighbors. It might be the first time in history where teaching the good parts of your history in school is considered an act of defiance, and where the higher-class and all the bien-pensants push distorted histories and documentaries that run down the country that hosts them.

Autoimmune. Systemic.

Sara A. Hoyt, “Auto-Immune — A blast from the past post from February 2013”, According to Hoyt, 2015-07-01.