So who is up for some side bets on Obamacare?

I’m sympathetic to the opinion that introducing a huge, complicated, government-run program is just asking for trouble. On the other hand, the Adams Rule of Slow-Moving Disasters says everything will work out.

As a reminder, The Adams Rule of Slow-Moving Disasters says that any disaster we see coming with plenty of advance notice gets fixed. We humans have a consistent tendency to underestimate our own resourcefulness. For example, the Year 2000 bug was a dud because we saw it coming and clever people rose to the challenge. In the seventies, we thought the world would run out of oil but instead the United States is heading toward energy independence thanks to new technology.

Obamacare is a classic slow-moving disaster. Absent any future human resourcefulness, it just might be a nightmare. But my money says that clever humans will figure out how to tame the beast before it triggers the collapse of civilization.

If betting were legal, I’d bet $10,000 that in ten years the consensus of economists will be that Obamacare had a lot of problems but that overall it was neutral or helpful to the economy. I base that hypothetical bet on The Adams Rule of Slow-Moving Disasters, not on the scary first-year state of the law. And I reiterate that I know next-to-nothing about the details of Obamacare. I’m just working off of pattern recognition.

Scott Adams, “Obamacare – Side Bets”, Scott Adams Blog, 2013-10-18

October 21, 2013

October 18, 2013

October 9, 2013

Craft brewers against the big breweries in North Carolina

The rising tide of craft brewing runs up against the entrenched political interests of the big brewers in Raleigh:

North Carolina politicians in Raleigh like to say they’re pro-jobs and pro-business.

But what happens when lawmakers are forced to pick sides between new, small businesses growing jobs and big legacy businesses trying to hold on to the market share they’ve got? Would it help you to know that the big legacy companies give hundreds of thousands of dollars in campaign contributions and the new small businesses are not yet organized?

There’s just such a battle brewing in North Carolina over beer — and who gets to distribute and market it. It pits a growing number of small craft brewers against big distributors. And the big distributors who are among the largest campaign contributors have state lawmakers on their side.

The number of craft breweries in North Carolina is growing rapidly. The state ranks 10th in the country in the number of craft breweries (70) but drops to 19th in overall beer production. Some small brewers say they could grow faster and generate more local jobs in North Carolina if lawmakers weren’t forcing them to hire outside distributors.

Lawmakers capped the amount of beer brewers can make before they are forced to hire outside distributors to transport and market their product. The law sets the cap at 25,000 barrels per year or 775,000 gallons.

One Charlotte brewer is joining others in pushing back against the cap — saying it’s bad for business and a job killer.

Update: I guess it would help if I included the link to the original article…

October 6, 2013

Any GMO-labelling compromise is a win for big business and a loss for everyone else

Baylen Linnekin explains why compromise in the battle over genetically modified food ingredients is likely to be heartily supported by big business — because they can easily cover costs that their smaller competitors will not be able to afford:

Like it or not — and I’m in the not camp — a mandatory, uniform national GMO labeling scheme appears increasingly likely.

[…]

Major players on the business side, including Walmart, America’s leading grocer, and General Mills, which bills itself as “one of the world’s largest food companies,” have publicly tipped their hands that they’d support some sort of mandatory labeling.

As I noted this summer, Walmart held a meeting with FDA officials and others from the food industry earlier this year where, it was alleged, the grocer and other food sellers that have opposed state labeling requirements would push for the federal government to adopt a national GMO labeling standard.

And just last week, Ken Powell, the CEO of General Mills, announced at the company’s annual stockholders’ meeting that the company “strongly support[s] a national, federal labeling solution.”

Powell’s comments are a game changer.

But do they mean that anti-GMO activists and food companies are on the same page? Not by a longshot. Powell made clear in his remarks that the company supports “a national standard that would label foods that don’t have genetically engineered ingredients in them, rather than foods that do.” (emphasis mine)

I suspect that anti-GMO activists would hate that solution because it wouldn’t provide the “information” they want and because all of the significant testing and labeling costs of the mandatory scheme Powell suggests — along with any liability for not testing GMO-free foods or for mislabeling — would be borne by the GMO-free farmers and food producers they frequent (and by their customers, in the form of higher prices).

October 3, 2013

Everything old is new again … this time it’s mead making a comeback

BBC News Magazine looks at the rise of modern-day mead in the North American market:

Long relegated to the dusty corners of history, mead — the drink of kings and Vikings — is making a comeback in the US.

But what’s brewing in this new crop of commercial meaderies — as they are known — is lot more refined from the drink that once decorated tables across medieval Europe.

[…]

Mr Alexander is not the only one to have caught on to the commercial potential of mead.

Vicky Rowe, the owner of mead information website GotMead, says interest in the product in the US has exploded in the past decade.

“We went from 30-40 meaderies making mead to somewhere in the vicinity of 250 in the last 10 years,” she says.

“I like to say that everything old is new again — people come back to what was good once.”

[…]

The mead of the past was often sweet, and didn’t appeal to many drinkers who were just looking for something good to pair with food. But mead has since changed.

“People don’t realise that just because it has honey in it, [mead] doesn’t need to be sweet,” says Ms Rowe, citing the proliferation of not only dry meads but also meads flavoured with fruits, herbs, and spicy peppers.

Yet hampering efforts towards building mead awareness is also the name mead itself.

Technically, mead is classified as wine by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, which regulates alcohol sales and labelling in the US.

This means that mead has to be labelled as “honey wine”, which doesn’t help combat people’s perception of the drink as being as cloyingly sweet.

“How do people recognise it as mead if you can’t say the word?” says Ms Rowe.

September 24, 2013

American governance – Kludgeocracy in action

Steven M. Teles on the defining characteristic of modern American government:

The complexity and incoherence of our government often make it difficult for us to understand just what that government is doing, and among the practices it most frequently hides from view is the growing tendency of public policy to redistribute resources upward to the wealthy and the organized at the expense of the poorer and less organized. As we increasingly notice the consequences of that regressive redistribution, we will inevitably also come to pay greater attention to the daunting and self-defeating complexity of public policy across multiple, seemingly unrelated areas of American life, and so will need to start thinking differently about government.

Understanding, describing, and addressing this problem of complexity and incoherence is the next great American political challenge. But you cannot come to terms with such a problem until you can properly name it. While we can name the major questions that divide our politics — liberalism or conservatism, big government or small — we have no name for the dispute between complexity and simplicity in government, which cuts across those more familiar ideological divisions. For lack of a better alternative, the problem of complexity might best be termed the challenge of “kludgeocracy.”

A “kludge” is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “an ill-assorted collection of parts assembled to fulfill a particular purpose…a clumsy but temporarily effective solution to a particular fault or problem.” The term comes out of the world of computer programming, where a kludge is an inelegant patch put in place to solve an unexpected problem and designed to be backward-compatible with the rest of an existing system. When you add up enough kludges, you get a very complicated program that has no clear organizing principle, is exceedingly difficult to understand, and is subject to crashes. Any user of Microsoft Windows will immediately grasp the concept.

“Clumsy but temporarily effective” also describes much of American public policy today. To see policy kludges in action, one need look no further than the mind-numbing complexity of the health-care system (which even Obamacare’s champions must admit has only grown more complicated under the new law, even if in their view the system is now also more just), or our byzantine system of funding higher education, or our bewildering federal-state system of governing everything from welfare to education to environmental regulation. America has chosen to govern itself through more indirect and incoherent policy mechanisms than can be found in any comparable country.

September 23, 2013

The growth of Canadian cities in the postwar era

Caleb McMillan has a brief history of the Canadian city after World War 2:

The end of World War 2 marks a good beginning point for this history. North American society went through some big changes and the cities reflect that. In Canada, The Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation was created and with it came the regulatory framework that vastly increased the government’s presence in housing. Government intervention — however — always has its unintended consequences. Post WW2, the Canadian government expanded its highway system, got involved in the mortgage business, and allowed provincial and municipal governments to plan and amalgamate city communities. Through monopoly power, central plans have a tendency to hollow out downtown cores that serve the interests of the market. The “Suburban City” is the result of government control over zoning laws and highway construction. These types of communities are sometimes very different from ones created by market means.

While high urban density can be viewed as good or bad, in terms of city functionality, density is a prerequisite for prosperity. City downtowns are market centres. Resources from the periphery are brought to market centres for trade, and within these centres live the people who deal with this market everyday. It has always been the rural farmers and trappers who were the ones on the edge of poverty — surviving the bare elements of nature to reap the rewards later in the city. The city was the centrepiece in the division of labour; a place to go to make a name of ones self. “Simple country living” that suburbia is supposed to reflect was always a Utopian dream. That somehow one could live out in the boonies yet receive the luxuries of a city.

The very idea of “simple country living” was probably an aristocratic notion that somehow took hold of the middle class imagination, because until the 20th century, only the upper classes could afford the luxury of maintaining a residence well outside the cities, yet still well-supplied with the comforts otherwise only available in the city.

This Utopian dream became a reality with the advent of the car. And with government roads, the possibility of suburbia became technically possible. But just because something is technically possible, doesn’t mean that it should necessarily be done. Market signals are the best means of discovering this information. Individual prices revealed through exchange embody information entrepreneurs use to discover consumer demand and determine scarcity. A major factor in Post WW2 Canada was exempt from this process. Roads, and the whole highway system, were already monopolized by the centralized state. The sudden profitability found in developing rural lands for residential purposes was aided by the non-market actions of building government roads.

Critics of suburban life (usually urban types themselves) are at least somewhat correct in their criticism of the suburbs:

But markets in the Suburban City are, in a way, non-existent. For many, the suburban home is an island of private life surrounded by other private islands. Everyone commutes somewhere. The suburban neighbourhood offers nothing more than residential homes, ensuring that streets remain empty and void of commercial activities. Children may play in the streets, but there is no natural adult supervision. Contrast this to a city neighbourhood, where the streets are the best places for children. With a mixture of commercial activity, residential homes, apartments and other city neighbourhoods immediately adjacent to either side — the presence of people is always guaranteed. There is a natural “eyes on the street,” where people ensure law and order through their everyday actions.

September 19, 2013

QotD: Guns and mental illness

There isn’t much of a culture-war component of discussing mental illness, other than a few folks on the Right who blame the Left for deinstitutionalizing the mentally ill in the 1960s. I suspect that there is no real constituency in favor of the Second Amendment rights of the mentally ill — provided, of course, the definition of “mentally ill” is clear, explicit, and taken seriously. (If you think there’s a stigma to admitting you’re seeing a therapist, a psychologist, or getting mental health treatment now, just wait until some of your legal rights can be restricted because of it.)

Thankfully, I’ve never known anyone who has had violent episodes or threatening mental illness. My sense of reading coverage and the literature is that people rarely “snap” and become dangerous killers overnight. As you’ve probably found in your research, there are certain common threads: withdrawal from others and lack of a support network; hostile behavior and temper control, outbursts, etc. It is maddeningly infuriating to hear friends and acquaintances of past shooters describe behavior that seems, in retrospect, to be a warning sign or red flag.

After Columbine, many school administrators tried to institute a new “If you see something, say something” approach to individuals behaving in a threatening manner. Then we saw in Virginia Tech that many, many students reported the gunman for strange and threatening behavior, including stalking. School administrators ultimately couldn’t do enough to stop him — either from fear of lawsuits or from overall bureaucratic inertia.

[…]

It’s not clear how effective a program like this would be; one would hope that people would already know to report strange, troubling, or threatening behavior to authorities. In past writings, I’ve emphasized that the only authority that can put someone on the federal firearms restriction list is a judge, and so that these sorts of concerns are best sent directly to the cops, not to a school administrator or company HR department.

However, a country where more Americans are trained to spot signs of serious, untreated and potentially dangerous mental illness strikes me as a better path than yet another effort to restrict the rights of 40 million gun owners because of the actions of a handful.

Jim Geraghty, “Why Post-Shooting Gun-Control Debates Are So Insufferable”, National Review Online, 2013-09-18

September 18, 2013

Reason.tv: Detroit’s Operation Compliance

“Someone breaks in, they never show up. Yet still, they want to come and blackball you and close your business,” says Derek Little, owner of an auto shop along Detroit’s Livernois Avenue.

He’s one of many business owners in Detroit who’s faced what he says amounts to harassment from the city’s overzealous code enforcement. Amidst a bankruptcy and a fast-dwindling population and tax base, the city has prioritized the task of ensuring that all businesses are in compliance with its codes and permitting. To accomplish this, Mayor David Bing announced in January that he’d assembled a task force to execute Operation Compliance.

Operation Compliance began with the stated goal of shutting down 20 businesses a week. Since its inception, Operation Compliance has resulted in the closure of 383 small businesses, with another 536 in the “process of compliance,” according to figures provided to Reason TV by city officials.

But business owners say that Operation Compliance unfairly targets small, struggling businesses in poor areas of town and that the city’s maze of regulations is nearly impossible to navigate, with permit fees that are excessive and damaging to businesses running on thin profit margins.

September 17, 2013

The flaw in “nudging”

Coyote Blog looks at the flourishing “nudge” sector of government activity and points out one of the biggest flaws:

The theory behind the idea that government should nudge (or coerce, as the case may be) us into “better” behavior is based on the idea that many people are bad at delay discounting. In other words, we tend to apply huge discount rates to pain in the future, such that we will sometimes make decisions to avoid small costs today even if that causes us to incur huge costs in the future (e.g. we refuse to walk away from the McDonalds french fries today which may cause us to die of obesity later).

There are many problems with this theory, not the least of which is that many decisions that may appear to be based on bad delay discounting are actually based on logical and rational premises that outsiders are unaware of.

But the most obvious problem is that people in government, who will supposedly save us from this poor decision-making, are human beings as well and should therefore have the exact same cognitive weaknesses. No one has ever managed to suggest a plausible theory as to how our methods of choosing politicians or staffing government jobs somehow selects for people who have better decision-making abilities.

September 11, 2013

September 4, 2013

“Despite a rash of deadly train crashes…”

Coyote Blog indulges in a good old-time fisking of an article built on the claim that there has been a “trend” of increasingly deadly railway accidents:

The best way to explain the phenomenon is with an example, and the Arizona Republic presented me with a great one today, in the form of an article by Joan Lowy of the Associated Press. This in an article that reads more like an editorial than a news story. It is about the Federal requirement for railroads to put safety electronics called Positive Train Control (PTC) on trains by a certain date. The author has a pretty clear narrative that this is an absolutely critical piece of equipment for the public good, and that railroads are using scheming and lobbying to unfairly delay and dilute this critical mandate (seriously, I am not exaggerating the tone, you can read it for yourself.)

My point, however, is not to challenge the basic premise of the article, but to address this statement in her opening paragraph (emphasis added).

Despite a rash of deadly train crashes, the railroad industry’s allies in Congress are trying to push back the deadline for installing technology to prevent the most catastrophic types of collisions until at least 2020, half a century after accident investigators first called for such safety measures.

The reporter is claiming a “rash of deadly train crashes” — in other words, she is saying, or at least implying, that there is an upward trend in deadly train crashes. So let’s ask ourselves if this claimed trend actually exists. She says it so baldly, right there in the first seven words, that surely it must be true, right?

[…]

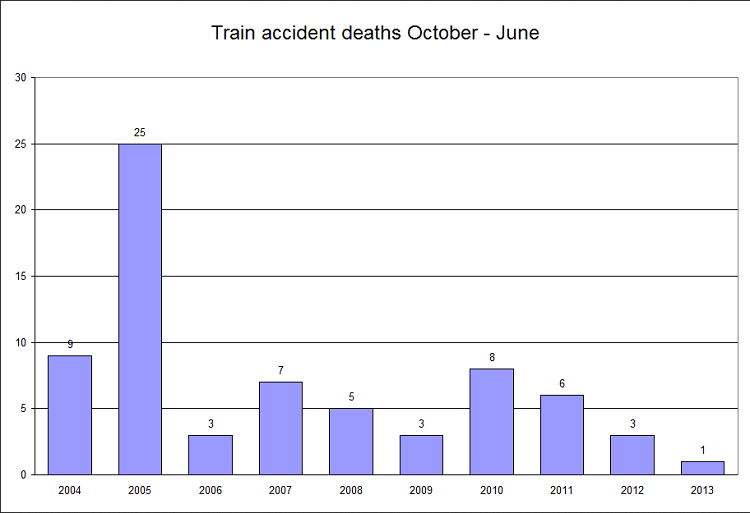

So let’s go to the data. It is actually very easy to find, and I would be surprised if Ms. Lowy did not actually have this data in her hands. It is at the Federal Railway Administration Office of Safety Analysis. 2013 data is only current through June and seems to be set up on an October -September fiscal year. So I ran the data only for October-June of every year to make sure the results were comparable to 2013. Each year in the data below is actually 9 months of data.

By the way, when one is looking at railroad fatalities, one needs to understand that railroads do kill a lot of people every year, but the vast, vast majority of these — 99% or more — are killed at grade crossings. People still do not understand that a freight train takes miles to stop. (see postscript below, but as an aside, I would be willing to make a bet: Since deaths at grade crossings outnumber deaths from collisions by about 100:1, I would be willing to bet any amount of money that I could take the capital the author wants railroads to invest in PTC and save far more lives by investing it in grade crossing protection. People like Ms. Lowy who advocate for these regulations never, ever seem to consider prioritization and tradeoffs.)

Anyway, looking at the data, here is the data for people killed each year in US railroad accidents (as usual click to enlarge any of the charts):

So, rather than a “rash”, we have just the opposite — the lowest number of deaths in a decade. One. I will admit that technically she said rash of “fatal accidents” and this is data on fatalities, but I’m going to make a reasonable assumption that one death means one fatal accident — which certainly cannot be higher than the number of fatal accidents in previous years and is likely lower.

Most of you will agree that this makes the author’s opening statement a joke. Believe it or not — and this happens a surprising number of times — this journalist is claiming a trend that not only does not exist, but is of the opposite sign.

August 18, 2013

Down with the “nudgers”

In Reason, Baylen Linnekin discusses the so-called libertarian paternalists:

Even if I were to concede that point, there are plenty of programs that might be called soft or libertarian paternalism and that yield negative outcomes.

For example, federal farm subsidies quietly influence the choices made by farmers and consumers and lead many in both groups to believe they’re better off — a key precept of libertarian paternalism.

Subsidies influence farmers to produce some foods (like corn, soy, dairy, and sugar) to the exclusion of other foods (like arugula, bok choy, and yams). It’s no surprise that the former foods are the ones most farmers grow, and that they’re much more frequent choices among eaters.

The noodgy allure of farm subsidies is that farmers get money and certainty, while consumers get abundant and cheaper food at the grocery.

Another example of libertarian paternalism around food is menu labeling. Its proponents refer to laws mandating calorie counts on fast food and other restaurant menus as a gentle nudge that requires businesses to provide us with information the government thinks we need but still allows us to make our own choices. The hope by government is that we’ll choose items with fewer calories and be better off for exercising that choice. But studies have shown mandatory restaurant menu labeling does not work in practice. Worse, a recent study showed mandated menu labeling can actually cause consumers to choose foods with more calories.

So both farm subsidies and mandatory menu labeling present firm empirical evidence that libertarian paternalism doesn’t work, right?

You might think so. But Sunstein’s Nudge writing partner, Richard Thaler, would likely argue that these failures simply call for more testing on the part of government.

“No one knows the answers to every problem, and not every idea works, so it is vital to test,” Thaler said earlier this month.

Of course. Who else but a cadre of bureaucrats who’ve never met you could possibly through trial and error determine what’s best for you to eat?

August 10, 2013

Counter-productive attempts to ease the housing crisis for the very poor

Sometimes the very tools employed to solve problems can make the problem worse:

Progressives routinely deplore the “affordable housing crisis” in American cities. In cities such as New York and Los Angeles, about 20 to 25 percent of low-income renters are spending more than half their incomes just on housing. But it is the very laws that Progressives favor — land-use policies, zoning codes, and building codes — that ratchet up housing costs, stand in the way of alternative housing options, and confine poor people to ghetto neighborhoods. Historically, when they have been free to do so, poor people have happily disregarded the ideals of political humanitarians and found their own ways to cut housing costs, even in bustling cities with tight housing markets.

One way was to get other families, or friends, or strangers, to move in and split the rent. Depending on the number of people sharing a home, this might mean a less-comfortable living situation; it might even mean one that is unhealthy. But decisions about health and comfort are best made by the individual people who bear the costs and reap the benefits. Unfortunately today the decisions are made ahead of time by city governments through zoning laws that prohibit or restrict sharing a home among people not related by blood or marriage, and building codes that limit the number of residents in a building.

Those who cannot make enough money to cover the rent on their own, and cannot split the rent enough due to zoning and building codes, are priced out of the housing market entirely. Once homeless, they are left exposed not only to the elements, but also to harassment or arrest by the police for “loitering” or “vagrancy,” even on public property, in efforts to force them into overcrowded and dangerous institutional shelters. But while government laws make living on the streets even harder than it already is, government intervention also blocks homeless people’s efforts to find themselves shelter outside the conventional housing market. One of the oldest and commonest survival strategies practiced by the urban poor is to find wild or abandoned land and build shanties on it out of salvageable scrap materials. Scrap materials are plentiful, and large portions of land in ghetto neighborhoods are typically left unused as condemned buildings or vacant lots. Formal title is very often seized by the city government or by quasi-governmental “development” corporations through the use of eminent domain. Lots are held out of use, often for years at a time, while they await government public-works projects or developers willing to buy up the land for large-scale building.

July 23, 2013

The maple-flavoured Leviathan

Richard Anderson on the PM’s latest cabinet shuffle and the media’s focus on the personalities rather than their actual performance:

Perhaps if we looked too closely we might start asking questions. Like why a nation of 34 million needs 39 cabinet ministers? Abraham Lincoln was able to free the slaves, save the Union and encourage the settlement of the American West with a mere eight cabinet ministers. And this with a government run without computers, telephones or even typewriters. Just paper, ink and a few thousand miles of telegraph wires. The population of the whole of the United States in 1860, both North and South, was 31.4 million.

But in those days governments were confined to hum-drum matters, such as winning immensely bloody wars and subsidizing the occasional transcontinental railroad. Today the remit of the state is far more ambitious. Beyond maintaining public order and some key bits of infrastructure, the modern state takes it upon itself to educate, scold, monitor and regulate virtually every facet of modern life. Thus, in a sense, we need 39 wise men and women to govern over us. We would likely need 39,000 and there would still be work left undone.

Except such a feat is impossible. You cannot plan an economy, much less something even more complex such as a whole society, from a few office buildings in Ottawa. When those in charge are non-experts rotated in and out based on political expediency, the result is what Mises called planned chaos. Actual experts might even do worse. No one is really in charge of the Leviathan state. No matter how powerful Stephen Harper seems, he cannot fight against the full weight of bureaucratic inertia. He might, if he felt ambitious, give a few hard kicks.

[…]

Ask any halfway educated Canadian, say the typical university graduate, why exactly Canada needs a Minister of State for Sport and you will get no clear answer, not even a half decent guess. Apply the same question to a professor of political science and you will get no better response. Ask a senior bureaucrat you will get not response at all, except a stream platitudes each less discernible than the last. Yet all will swear that Canada needs a Minister of State for Sport. I mean, what have you got against Sport? Or Multiculturalism? Or Western Economic Diversification?

Since no decent consensus fearing Canadian objects to these things in and of themselves, they do not object to them being supervised, managed, regulated or subsidized by the government. Modern Canada’s true and unquestioned stamp of approval on any facet of everyday life is government authorization. No action or thought is truly noble unless a government department has been consecrated in its name.

Blessed is the name of the Minister of State for Western Economic Diversification.