Ted Campbell continues his series on how to reform the Canadian Forces, this time looking at the overall command and control structure:

How the nation’s armed forces should be organized is a topic of nearly endless debate amongst military people. It is no secret, I think, that I favoured the joint force structure that former Defence Minister Paul Hellyer introduced in the 1960s. I was less enamoured with his idea of functional commands, but it was hard to strike a balance. I like the American model of joint, regional commands.

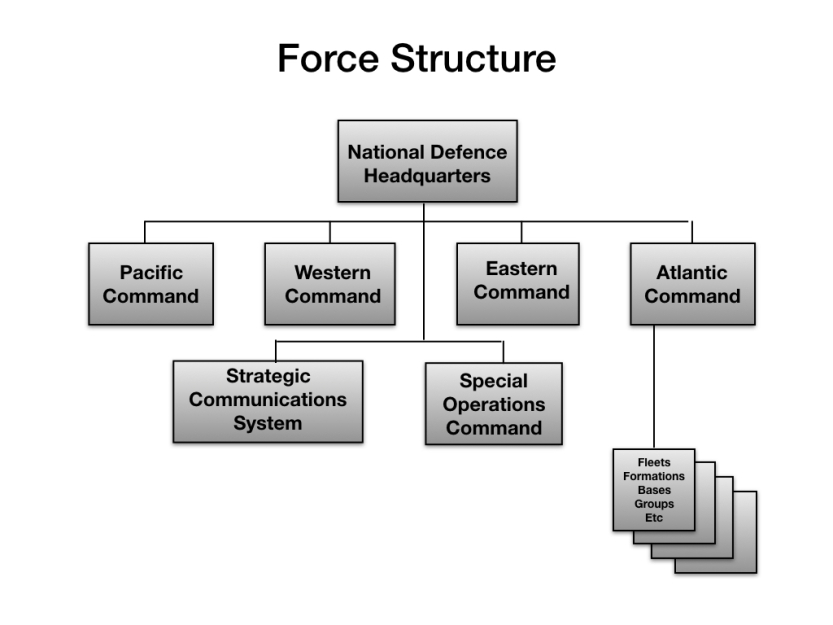

There is, almost always, a need for a few, national, functional organizations ~ for special forces and, perhaps global, strategic command, control and communications (C³) ~ but, in general, I believe that one large, national, strategic/operational HQ can control a half dozen commands, say four or five regional and two or three functional, something like this:

In my model (which reflects my deeply personal and often idiosyncratic views) the three star* Chief of the Defence Staff, in Ottawa, would command, just for example, four two star regional joint commanders (rear admirals or major generals) who would, in their turn, command almost every formation, base, depot, dockyard, base, combat ship and combat brigade, unit or wing in their geographic area. There would be a few exceptions ~ the one star officer (commodore or brigadier general, perhaps only a Navy captain or Army/RCAF colonel is needed) commanding the Strategic Communications System would command the specialized units scattered across the country and, indeed, around the world, but those units would get their day-to-day administrative and logistical support from their regional commander. Ditto for the one star officer commanding the Special Operations Command … except that he might need to have a bit more administrative and logistical power because of the nature of his business. There might be a perceived need for a separate Joint Operations (Overseas) Command but I doubt it is really necessary. The national Joint Staff (headed by a two star officer) in Ottawa can plan and direct the mounting of operations and each regional command should have a one star deputy commander who has a deployable HQ than can go, by sea and or air, to any trouble-spot in the world on fairly short notice.

In my model it seems obvious that Pacific and Atlantic Commands are going to be, primarily joint Navy/Air commands, likely, usually, commanded by a Navy rear admiral or an RCAF major general while Western and Eastern Commands will be, mainly, joint Army/Air commands, usually commanded by Army or RCAF major generals, but, if (s)he is the best person available there is no reason why an Army major general could not command Pacific Command and no reason why a Navy rear admiral could not command Western Command, for example. The commanders will have real commands, full of fighting and support forces … things like the current Canadian Forces Intelligence Command, will revert to being staff branches in the national HQ and the units will be part of the joint commands. Similarly, the Chiefs of the Naval, General and Air Staffs will be the professional heads of their services, responsible for things like doctrine, individual training standards and equipment requirements, but they will not be commanders.

[…]

* One of my critics has chided me for using the term “stars” when we, Canadians, don’t put stars on admirals’ and generals’ shoulders, rather they have maple leaves to indicate the level of their rank … fair enough, except that he is, as we used to say, “picking the fly sh!t out of the pepper” because I’m not using “slang”, as he suggests, but rather, I am using that was, when I served, and I understand is, still, common parlance in Canada and amongst our allies, including in the UK and Australia, too.