Tommy Westphall’s Snowglobe

Published 14 Jan 2020The dynamic duo’s show of the 60s was fond of celebrity cameos. Here is a Supercut of every single one of them.

In order of appearance:

1. Jerry Lewis

2. George Cisar (from the 1966 film)

3. Dick Clark

4. Van Williams and Bruce Lee as The Green Hornet and Kato from The Green Hornet

5. Sammy Davis Jr.

6. Bill Dana as José Jiménez

7. Howard Duff as of Sam Stone from Felony Squad

8. Werner Klemperer as Colonel Klink from Hogan’s Heroes

9. Ted Cassidy as Lurch from The Addams Family

10. Don Ho

11. Santa Claus

12. Art Linkletter

13. Edward G. Robinson

14. Suzy Knickerbocker

15. The Carpet King

(more…)

November 12, 2022

SUPERCUT – Every Window Cameo in Batman (1966-1968)

November 8, 2022

Look at Life — Underwater Menace (1969)

PauliosVids

Published 20 Nov 2018Dealing with the hazardous legacy of World War II.

October 7, 2022

Pease Pudding – Weird Stuff In A Can #74

Atomic Shrimp

Published 28 May 2018This is Pease Pudding — A sort of spreadable paste made from yellow split peas, and with a very long history as a staple food in England.

Here’s the link to the article on Atomic Shrimp (includes a recipe, of sorts): http://atomicshrimp.com/post/2007/01/…

October 4, 2022

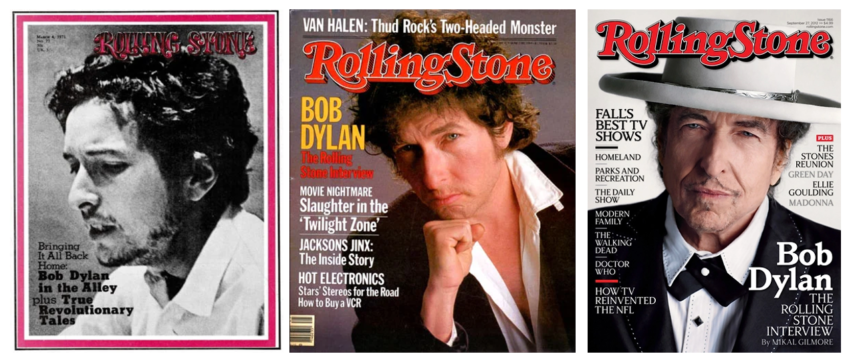

“On the cover of the Rolling Stone“

Ted Gioia discusses the oddly nostalgic turn modern music writing has taken:

The first thing you notice is the sheer abundance of music magazines on display. We must truly be living in a golden age of music writing if it can support so many periodicals.

I was very happy to see this — at least at first glance.

But at second glance, I started to notice the cover stories.

Lavish attention is devoted here to artists who built their audience in the last century — Miles Davis, David Bowie, Buddy Holly, Blondie, Led Zeppelin, Björk, Motorhead, The Cure, etc. That’s an impressive roster of artists (well, most of them), but they don’t really need the publicity nowadays — they were legends before many of us were born.

Even the magazine names reveal a tilt toward nostalgia. I can’t make out the titles in their entirety, but I see the words Retro, Vintage, and Classic. Publishers are shrewd people, and they don’t put these words in large font unless the audience responds to them.

Maybe print media is nostalgic by definition — if, as we’re repeatedly told, young people don’t read things on paper. (I’m skeptical of that claim, but I hear it all the time.) Yet when I visit the websites, I see the same backward glance. You can’t click on Rolling Stone‘s homepage or Twitter feed without finding some massive list article — touting the “100 Best Songs of 1982” or “The 100 Greatest Country Albums of All Time“. You will find similar retro celebrations at almost every other music media website with a large crossover readership.

Editors love lists nowadays, especially of all-time greats. If I pitch an article like that, the whole editorial team starts salivating — you can even feel the moisture over Zoom — in sharp contrast to any proposed article on a young, unproven musician. Those pitches get pitched right back in your face. You might conclude that we have now arrived at the end of history, with all greatness residing in the past. The editors, at least, must think so.

Things weren’t always like this. Go back and look at old issues of Rolling Stone or Downbeat or some other music magazine — there were years in which every cover story was about a living person and usually someone young with something new to say.

Those days are gone. But here’s the most ironic fact of all — the actual cover stories haven’t changed.

By the way, I’d like to know when Rolling Stone published its first “all-time greats” list — that was the moment when nostalgia first entered the rock bloodstream, a vital force previously resistant to sentimental yearnings for the past.

September 13, 2022

Down the Line – A look into the legacy of the cuts made to the rail network by Doctor Beeching (2008)

Kevin Birch

Published 29 Jul 2013Joe Crowley meets the people who battled to save their local railway lines in the South of England in the 1960’s.

First aired on BBC One 26th October 2008

September 10, 2022

The Land Rover Defender Story

Big Car

Published 27 Dec 2019The Land Rover is Britain’s bullet-proof off-roader born out of Rover’s post-war desperation and became the indispensable go-anywhere vehicle. Like its famed bullet-proof ruggedness, Land Rover production kept going, and going, and going. But with a brief gap of 4 years, the Land Rover is still with us and looks like it’s not going away any time soon.

(more…)

September 8, 2022

Queen Elizabeth II (21 April, 1926 – 8 September, 2022)

It was inevitable that the Queen would die, yet the news was still an unwelcome surprise and a shock. I shared the news on social media, and as you’d expect, the very first response was from someone clearly looking for a fight over the monarchy and the bugaboos of his current obsessions. Thank goodness for the “mute” function. Prince Charles is now the King, although I understand he plans to choose a different regnal name.

In The Critic, Ben Sixsmith looks at the Queen’s reign in retrospect:

Queen Elizabeth II signs Canada’s constitutional proclamation in Ottawa on April 17, 1982 as Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau looks on.

The Canadian Press/Stf-Ron Poling

For years, Queen Elizabeth II was a link to another age — an age of tradition, and respect, and restraint. Did that age ever exist in an ideal form? Of course not. But we still admire its echoes, which surrounded our conception of the Queen.

She was crowned in 1953, looking rather vulnerable at the age of 25. Winston Churchill was Prime Minister. Man had only just reached the top of Everest and was more than fifteen years away from reaching the Moon.

The Empire was crumbling but the young, elegant, stoical Queen kept alive a sense of British importance and stability. Her personal calmness and courage as she toured dangerous regions was noted (and would be later tested when Michael Fagan, a disturbed socialist, snuck into her bedroom).

Her popularity never faltered. Governments, institutions, actors, athletes et cetera have risen and fallen in their popular esteem but Her Majesty was always loved. Was this in part because our exposure to her was so limited? Of course. But there is something special in that. She never imposed herself upon the public. She was committed to the tiring, traditional, constitutional, life-affirming, often rather modest and unheralded duties that she had inherited. The monarchy is a lot more than one person, of course, but it took a special person to embody it.

All the way back in the 1950s, Malcolm Muggeridge warned that elevating royals to the status of celebrities would kill the institution. Who could deny that he was onto something? Princess Diana was drowned in prurience and sentimentality, and some of the Queen’s own descendants have disgraced themselves, to greater and lesser degrees, by embracing the sordid lifestyles and the haughty status of the rich and the famous. Throughout it all, Queen Elizabeth maintained her dignity and grace, and her focus on her own responsibility.

The CBC posted an obituary for Her Majesty as soon as the news was confirmed:

Queen Elizabeth, Canada’s head of state and the longest-reigning British monarch, has died.

She died on Thursday afternoon at Balmoral Castle in Scotland, Buckingham Palace said in a short statement. She was 96.

“The Queen died peacefully at Balmoral this afternoon. The King and The Queen Consort will remain at Balmoral this evening and will return to London tomorrow,” the palace said, in reference to the Queen’s son Charles, who automatically became king upon her death, and his wife, Camilla.

Her husband, Prince Philip, died in April 2021.

Elizabeth became Queen in 1952, at the relatively tender age of 25, and presided over the country and the Commonwealth, including Canada, for seven decades. Those 70 years as monarch were recognized during this year’s Platinum Jubilee events, which reached their height in London in early June.

In her time as monarch, Elizabeth bore witness to profound changes at home and abroad, including the decline of the British Empire and decolonization of many African and Caribbean countries, along with the end of hostilities with Irish republicans.

As one of the most famous women in the world, she was also under great public scrutiny during some of the most painful moments of her life, including the death of her father, King George VI, the marriage breakups of three of her four children and the death of her former daughter-in-law, Diana, Princess of Wales.

But Elizabeth always had a keen sense of her role.

“I cannot lead you into battle, I do not give you laws or administer justice,” she said during her first televised Christmas address in 1957. “But I can do something else: I can give you my heart and my devotion to these old islands and to all the peoples of our brotherhood of nations.”

In the National Post, Araminta Wordsworth points out the Queen’s fondness for Canada during her reign:

“Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II” by Tinker Sailor Soldier Spy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 .

After a record-breaking reign of 70 years Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth died on Sept. 8, 2022.

She was the longest-ruling British monarch, outpacing her great-great-grandmother, Queen Victoria. However, Louis XIV of France still holds the absolute record, with 72 years, 100 days.

For most Canadians, the 96-year-old is the only sovereign they have ever known, but whether the country will sustain the connection after her death remains to be seen.

Certainly, Canada was the country she chose to visit most often. She was also here at one of the pivotal moments in our history when then-prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau brought home the Constitution in 1982. As sovereign, she signed the document in a rain-spattered and windy ceremony on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, the capital chosen by Queen Victoria.

But her connection to Canada had begun decades earlier. In 1939, Princess Elizabeth was reportedly the first British royal to make a transatlantic phone call: the recipients were her parents, then the Duke and Duchess of York, who were on a North American tour.

In 1951, the princess spent almost five weeks in Canada, filling in for her ailing father, George VI.

Winston Churchill, then in opposition, had wanted the princess and her husband, Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, to travel by boat, arguing air travel was unsafe.

But he was overruled and the royal couple became the first to embark on such a tour by air. With an action-packed schedule, they crossed the country from the Atlantic to the Pacific, including a side trip to Washington, D.C., greeted all the way by rapturous crowds. The royal pair square-danced, attended a hockey game and accepted countless bouquets.

August 28, 2022

QotD: Hell’s inhabitants

Over large expanses of magnificent farmland, there has now spread a circuit-board of suburban sprawl, and along all approach roads the strip-mall phenomenon, of franchise capitalism at its most ghastly. City planners and surveyors worked it all out. Fifty years, and almost everything I loved has been wantonly destroyed. But thanks to those Google “street views”, I can see that the same has happened almost everywhere else I have ever been. We’re still calling it “progress”, and it is still leading us by the straightest possible line, to Hell.

[…]

I haven’t actually been to Hell, but I’m told it is full of surveyors and planners.

David Warren, “Esquesan”, Essays in Idleness, 2019-04-10.

August 15, 2022

Look at Life – Goodbye, Picadilly (1967)

nostalgoteket

Published 1 Sep 2011U.K. Newsreel. A look at the Piccadilly Circus of the Swinging Sixties! A lot of what is shown here no longer exists as it was soon “modernized” to meet the demands of a changing world. Also a look at underground Piccadilly to see sights that few people have ever seen.

August 11, 2022

Nostalgia seen as harmful

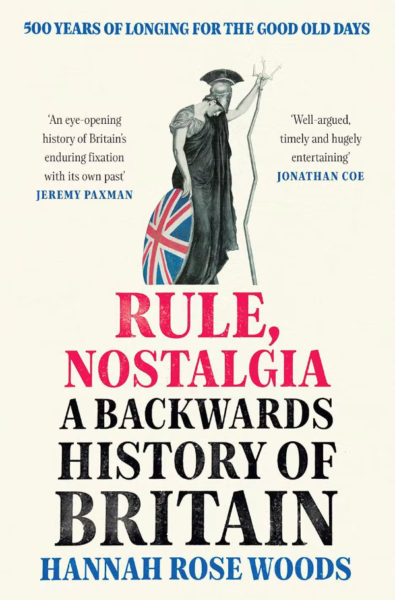

In The Critic, Michael Ledger-Lomas reviews a new book that is critical of Britain’s chronic case of nostalgia for “the good old days”:

Indulging in pained regret for lost times might seem a harmless pleasure, but Hannah Rose Woods is here to warn it has become a pathological “fixation”. The Right, she argues, has “weaponised” nostalgia, tapping “inchoate yearnings about fading pride and glory” to fuel hatred against historians who are simply “putting the facts back in” to the national “storybook”.

Apparently, the first cure for this “peculiarly English affliction” involves refuting errors and egregious simplifications in Tory talk about the national past. Woods is an inveterate Tweeter and her Rule, Nostalgia often works like a book-length version of the “Hi, historian here” threads that infest that medium.

The Government exhorted people to get through Covid by showing the Blitz spirit, but historians know German bombing caused as much fear and resentment as pride and resolve. Britons were supposed to Keep Calm and Carry On, “but this was a fantasy”, Woods writes, because the 1940s poster with that motto never entered circulation. The tea towels lied to us.

Woods is more productive when she probes nostalgia as a cluster of emotions, rather than condemning it as a set of errors. For like all emotions, it can be usefully historicised. This insight shapes the basic structure and approach of the book, which is more ironic than irate. Our times seem to be gripped by nostalgia for the days before yesterday, but the sixties, seventies and eighties abounded with yearning for the simplicities of the Second World War.

The thirties and forties were, in turn, full of voices lamenting what one of Orwell’s heroes called the “newness of everything”, pining for the sun-dappled afternoons of Edwardian England. The Edwardians themselves lamented the lost certainties of the high Victorian age and fretted that rural tranquillity was on the wane. And so on. Woods turns the periods of our history into Russian dolls of nostalgia, each nested within the other.

It is an engaging literary device which palls as succeeding chapters ask readers to re-enact their surprise that apparently stable times were consumed with anxiety about losing touch with tradition. Woods says the “calmly elegant Georgian heyday” fretted about whether Britain should go global or remain a tight little island, while it would be a “hard sell” to claim that the age of the Reformation and the Civil War was an “age of contentment and stability”. Well, quite.

The further Woods progresses away from the “rancid Englishness” of the present, the more forgiving she becomes of nostalgia — or at least of wistful absorption in the past, which is not quite the same thing. She rightly sees that nostalgia has generally not been an obstacle to rapid social change — what bolder Victorians would have called “progress” — but has offered psychological compensation for them.

July 31, 2022

Look at Life — Pipeline (1961)

ian16th Jones

Published 20 Aug 2017Refuelling at Sea and in the Air 1960’s style

July 21, 2022

The Railrodder (1965)

NFB

Published 15 May 2015This short film from director Gerald Potterton (Heavy Metal) stars Buster Keaton in one of the last films of his long career. As “the railrodder”, Keaton crosses Canada from east to west on a railway track speeder. True to Keaton’s genre, the film is full of sight gags as our protagonist putt-putts his way to British Columbia. Not a word is spoken throughout, and Keaton is as spry and ingenious at fetching laughs as he was in the old days of the silent slapsticks.

Directed by Gerald Potterton – 1965

July 11, 2022

British Transport Films: Elizabethan Express (1954)

mikeknell

Published 6 May 2014This 1954 documentary is uploaded in a couple of places, but here it is without breaks and in the correct aspect ratio. One of the classic railway films.

July 6, 2022

Look at Life — Playing Trains (1967)

June 16, 2022

Paul Wells takes in a current movie … and likes it

I’ve never been much of a movie-goer, even before the neverending pandemic lockdown theatre landed on us in 2020, so the chances of me going to see something like Top Gun: Maverick were pretty low (especially as I never bothered to watch the original, back in the day). Paul Wells is in the middle of a European trip, so he did what every travelling North American would do somewhere on the continent of history and culture: he watched a current-release American movie:

The mystery of Maverick is why, by next weekend, it will pass Doctor Strange in the Convolution of Fan Service as the year’s biggest movie, why it is the biggest film of Tom Cruise’s charmed life — why it strikes such a chord in this moment, even though its premises, visual vocabulary and soundtrack are 36 years old. In terms of chronological distance from the original Top Gun, it’s as though the top-grossing movie of 1986 had been a sequel to 1950’s Annie Get Your Gun. (“And there has never been a star as sensational as Betty Hutton!” Annie‘s trailer proclaims. Switch Tom Cruise in for poor Betty and suddenly the claim may actually be true.)

The simplest hypothesis is that Maverick is just big and loud, so you can leave your brain at home and enjoy the spectacle. But lots of lousy movies nobody watched were big and loud, including Matrix: Resolutions and Ghostbusters: Afterlife, so there must be some fuller explanation.

This being a Substack newsletter, I suspect I’m contractually encouraged to argue that Maverick wins because it isn’t woke. I’m afraid I can’t oblige. I mean, the movie definitely makes only the barest acknowledgment of taking place in the 21st century. None of the hotshot young recruits pauses from the action to specify their pronouns. None decorates their flight helmets with empty square brackets to acknowledge their privilege. The film’s few concessions to cultural change since the MTV era have the effect, not of engaging today’s fights on provocatively old-fashioned terms, but of declining to engage. Joseph Kosinski, the journeyman special-effects technician brought in to direct this film in note-perfect homage to the style of the original Top Gun director Tony Scott, doesn’t even bother to make the film’s racial politics as minimally complex as Scott did in 1995’s Crimson Tide. Maverick‘s young recruits, diverse in gender and ethnicity, are awesomely interchangeable in every other way. One smirks, one has a moustache; the others have no identifying characteristics. (When half the recruits get cut from the big mission at the 90-minute mark, there is no dramatic payoff because it’s impossible to tell these people apart. “Sorry, Component A, I’ve decided to go with Component B.”) Nobody under 30 in this film has sex for either pleasure or procreation. Yearning for intimate touch is plainly something only old people do, like writing in cursive script or owning books.

As a cultural argument, Maverick is so close to being tabula rasa that there’s no real point interrogating it. But on another front, it succeeds resoundingly in popular art’s primary function of tantalizing simplification. It started to make sense when I realized that Cruise’s character, despite the denial inherent in his call sign, is a career civil servant.

This is a movie about the action of a large modern state. It’s a film about public policy. Its central claim is a cathartic feat of Avengers-level denial. Just as the superhero movies offer us a made-up universe in which we have any hope of telling the good characters and the evil characters apart, Maverick posits a world in which modern governments can get anything done at all.

I may be influenced in this reading by the fact that I work in contemporary Ottawa. I’ve been writing variations on a simple question — Can Justin Trudeau get big things built? — since 2017. I’m hardly alone. And it’s hardly just a question about Trudeau, Ottawa or Canada. It’s been fun reading about chaos at Toronto’s Pearson airport, but last week the Financial Times ran a “big read” feature story about global airport chaos that didn’t even mention Pearson, Toronto or Canada. Joe Biden promised to Build Back Better. It’s not going great. Here in France, Emmanuel Macron is the first president to be re-elected in 20 years, a genuine feat, but it’s not going great. Brexit? Don’t ask.

A generic term for the ability of governments to do stuff is “state capacity”, and there’s a vague sense in the quasi-academic literature that it’s in decline, although, the real world being the real world, every element of this claim — that state capacity is declining, that it can be measured, that it even exists in any measurable form — is open to dispute. Still, it feels true, don’t it? The world was never great. In important ways it was worse than today. But it used to feel like it was possible to improve the thing, and now it just feels like everyone’s just firing blind and hoping for the best. COVID is a dynamite demonstration of this. Three successive Canadian federal health ministers were told, by a prime minister who prides himself on his ability to read the room, to get cracking on plain-paper packaging for tobacco products. And then the biggest public-health disaster of our lifetimes opened up its jumbo can of whup-ass, and it wasn’t even in the mandate letters. And it’s hard to blame anyone involved. All the chaos that has ensued had its roots in the original chaos. Real life doesn’t have a plot. As Homer Simpson said, it’s just a bunch of stuff that happens.