Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Jul 30, 2024A bowl of the original Corn Flakes made with only corn.

City/Region: Battle Creek, Michigan

Time Period: 1895Dr. John Kellogg was all about health, and when his brother, William (the financial brains of the operation), wanted to add sugar to the very bland original Corn Flakes, he flat out refused. Eventually, William bought the rights to Corn Flakes, changed the recipe, and the rest is history.

I don’t have the industrial rollers that the original recipe for Corn Flakes used, so I made a dough. The flakes turned out nice and crispy, but they are very bland. I would recommend using stone-ground cornmeal and adding some sugar and salt to make the whole process easier and the end product tastier.

Excerpt from Patent No. 558,393 [for] Flaked Cereals and Process of Preparing Same.

First. Soak the grain for some hours — say eight to twelve — in water at a temperature which is either between 40° and 60° Fahrenheit or 110° and 140° Fahrenheit, thus securing a preliminary digestion by aid of cerealin, a starch-digesting organic ferment contained in the hull of the grain or just beneath it. The temperature must be either so low or so high as to prevent actual fermentation while promoting the activity of the ferment. This digestion adds to the sweetness and flavor of the product.

Second. Cook the grain thoroughly. For this purpose it should be boiled in water for about an hour, and if steamed a longer time will be required. My process is distinctive in this step—that is to say, that the cooking is carried to the stage when all the starch is hydrated. If not thus thoroughly cooked, the product is unfit for digestion and practically worthless for immediate consumption.

Third. After steaming the grain is cooled and partially dried, then passed through cold rollers, from which it is removed by means of carefully-adjusted scrapers. The purpose of this process of rolling is to flatten the grain into extremely thin flakes in the shape of translucent films, whereby the bran covering (or the cellulose portions thereof) is disintegrated or broken into small particles, and the constituents of the grain are made readily accessible to the cooking process to which it is to be subsequently subjected and to the action of the digestive fluids when eaten.

Fourth. After rolling the compressed grain or flakes having been received upon suitable trays is subjected to a steaming process, whereby it is thoroughly cooked and is then baked or roasted in an oven until dry and crisp.

— John Harvey Kellogg. United States Patent Office, 1895

December 4, 2024

The Disturbing Origins of Kellogg’s Corn Flakes

August 25, 2024

“Does your vote count?” or how to set up an automatic vote-generation scheme

Elizabeth Nickson on recent reporting about voting scams in various US states:

After engineer and data scientist Kim Brooks worked on cleaning the voter rolls in Georgia for a year, she realized she was on a stationary bicycle. She’d clear a name for various reasons, dead, felon, stolen ID, living at a seasonal campground for twenty years, duplicate, moved out of state, 200 years old, etc., and back it would come within a month. At that juncture she realized that a program within the Georgia voter registration database was methodically adding back fake names.

She looked deeper. For new registrants, the culprit was principally Driver’s Services creating new registrations and in this case, the manufacturer was a person, or persons. Within the government office, someone was stealing names and duplicating, even tripling that person’s vote and then forging their signature. Sometimes it was someone who just died, or a teacher who had no voting record. In the case of a nurse who died in 2022 with three registrations, she was registered to vote in two counties, and all three of her voted in the 2022 election and the 2024 primary. Each signature was slightly different, the last three letters spelled, ly, ley, and lley

This operation works under AVR, or automatic voter registration, and is being used to register migrants. They will not vote, but their names have been entered into the Voter Registration database when they apply for a driver’s license and their vote will be voted for them. I imagine that this is repeating something everyone knows, but the borders are open for precisely this reason, so the Democrat/RINO machine can steal their votes. By the way, the process for advancing permanent residency has been cut from 11 months to two.

In 2020, twenty states used operation AVR. Of those, Trump lost 18.

That’s because there are registration fraud rings, as identified in the Arabella doc. and in the work of Omega4America. This worked well in Michigan, where, according to Captain Seth Keshel, who is one of the leads on this fight, believes that Trump likely got 576,443 more votes than were counted and won Michigan by 8.5%.

Every state is host to a dozen or more NGO’s which do nothing but fill out ballots for the faked registrants. Peter Bernegger’s team in Wisconsin has video of NGO functionaries doing just that in Wisconsin in 2020 at 1 am, early morning after Election Day.

Michigan has two million more registered voters than they should have. 83.5% of the state is registered to vote but only 77.9% is over 18. – Seth Keshel

Seth works with demographic trends and does detailed statistical analysis; travelling almost ceaselessly to teach Americans how to stop the cheat. AVR was launched in Michigan, after Trump’s win in 2016. By 2020 there were 547,460 net new registrants in Michigan. Today, more voters are registered to vote than there are people old enough to vote. Keshel:

Per Keshel’s analysis, the Democrats and RINOs are frantically operating a dying political coalition which began to shift hard after Obama’s performance in his first four years, when not only did nothing change for the working class, it worsened. Democrat registrations in Michigan collapsed to the point where the Dems lost 16,000 as of 2016. Enter AVR and boom, 500+K new registrants.

August 12, 2024

In Michigan, the mayor of Omena is Lucky

In The Free Press, Eric Spitznagel reports on the outcome of the most recent mayoral race in Omena, Michigan:

On July 20 in Omena, a small town in the “little finger” of northern Michigan, a crowd of about a hundred locals gathered in a church parking lot for the inauguration of their new mayor. A brass band played “The Stars and Stripes Forever” as Sally Viskochil, president of the local historical society, walked across the patriotically festooned stage to make the announcement.

“And our new mayor is …” There was a collective intake of breath. “Lucky!”

There was a smattering of applause, but a few members of the audience looked stunned. Mike McKenzie, 53, an Illinoisan with a summer home in Omena, turned to me, befuddled.

“Boy,” he said. “I guess people really are fed up with the old two-species system.”

Lucky, after all, is a horse. He’s a cross between an American Quarter and an American Paint, to be precise, and the first equid to be elected mayor of Omena. Until now, this race has only ever been won by a dog — and, once, a cat. You could say Lucky was an underdog in securing the town’s highest office, except he beat twelve actual dogs, five cats, and a goat. Many of them were in attendance. The victor was not.

As the results sunk in, Rosie, the incumbent mayor, a Golden Labrador mix, wandered around the crowd, saying her goodbyes. The band broke into “Hail to the Chief” for her, and she paused, as if to listen.

Welcome to Omena’s triennial animal election. What began as a fundraising stunt for the local historical society in 2009 is now a source of heated political debate in this middle-of-nowhere Michigan village, population 355. As the crowd began to disperse, a small group of locals gathered under a tree to escape the sun, and to talk frankly.

“The horse isn’t even from here,” groused Cathy Stephenson, the campaign manager for Topsy & Turvy, domestic shorthair cats who ran on one ticket to be co-mayors.

“But isn’t he moving here?” another woman asked. “That’s what I heard.”

“Well, he should’ve waited to run till he lives here full time,” Stephenson said.

Lucky, who is 16, has lived 2,000 miles away in Cave Creek, Arizona, his entire life. He was conspicuously absent throughout the summer campaign season — but allowed to run because his human relatives have owned property in Omena for three generations and plan to relocate here in the fall.

November 24, 2023

Freshwater Flattops; The Corn Belt Carriers Wolverine and Sable

[NR: These fascinating lake vessels first came to my attention back in 2013 – Lake Michigan’s carrier fleet.]

Ed Nash’s Military Matters

Published 8 Aug 2023Sources for this video can be found at the relevant article on:

https://militarymatters.online/

(more…)

November 4, 2021

Fallen Flag — the Milwaukee Road

This month’s Classic Trains fallen flag feature is the Milwaukee Road (MILW) by George Drury. As with most major US railways, the Milwaukee Road was a long-term collection of different railway lines, some merged for obvious economic benefit and others taken over to reduce competition, but the first of the components that eventually evolved into the Milwaukee Road system was the 1847 Milwaukee and Waukesha Railroad. This line was incorporated to connect the Wisconsin city of Milwaukee to the river traffic along the Mississippi River, and the corporate name was changed even before construction began to the Milwaukee and Mississippi Railroad to more adequately convey the purpose of the line. The first segment opened in November 1850 connecting Milwaukee and Wauwatosa, a distance of five miles, then to Waukesha a few months later, then to Madison, but not extending all the way to the river at Prairie du Chien until 1857.

This month’s Classic Trains fallen flag feature is the Milwaukee Road (MILW) by George Drury. As with most major US railways, the Milwaukee Road was a long-term collection of different railway lines, some merged for obvious economic benefit and others taken over to reduce competition, but the first of the components that eventually evolved into the Milwaukee Road system was the 1847 Milwaukee and Waukesha Railroad. This line was incorporated to connect the Wisconsin city of Milwaukee to the river traffic along the Mississippi River, and the corporate name was changed even before construction began to the Milwaukee and Mississippi Railroad to more adequately convey the purpose of the line. The first segment opened in November 1850 connecting Milwaukee and Wauwatosa, a distance of five miles, then to Waukesha a few months later, then to Madison, but not extending all the way to the river at Prairie du Chien until 1857.

In that year, another of the frequent financial crises of the era struck and the company struggled on for two years, but eventually went into receivership in 1859. New owner the Milwaukee and Prairie du Chien Railroad took possession in 1861. After the Civil War, the company was merged with the Milwaukee and St. Paul and in 1874 the combined railroad became known as the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul with the completion of a new line connecting with Chicago.

In the next few years the road built or bought lines from Racine, Wis., to Moline, Ill.; from Chicago to Savanna, Ill., and two lines west across southern Minnesota. The road reached Council Bluffs, Iowa, across the Missouri River from Omaha, in 1882, and reached Kansas City in 1887. In 1893 the CM&StP acquired the Milwaukee & Northern, which reached from Milwaukee into Michigan’s upper peninsula.

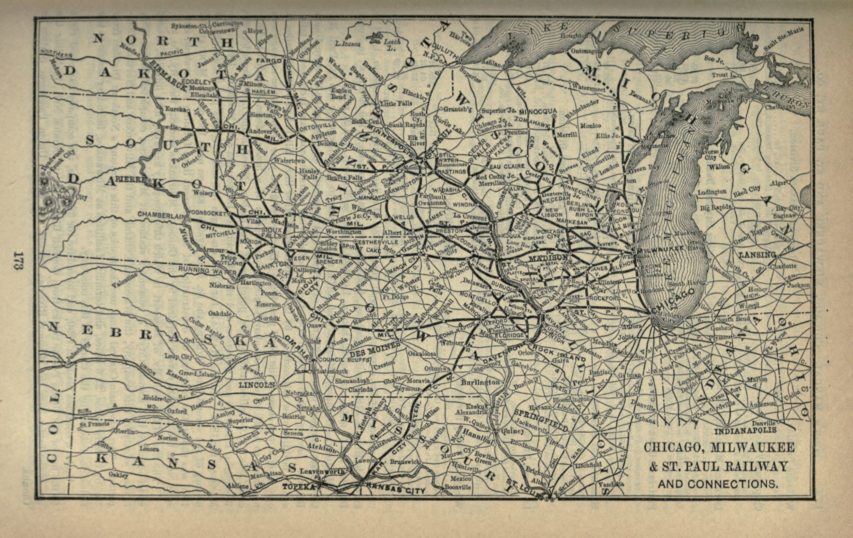

In 1900 the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul was considered one of the most prosperous, progressive, and enterprising railroads in the U.S. Its lines reached from Chicago to Minneapolis, Omaha, and Kansas City. Secondary lines and branches covered most of the area between the Omaha and Minneapolis lines in Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota. Lines covered much of eastern South Dakota and reached the Missouri River at three places in that state: Running Water, Chamberlain, and Evarts. Except for the last few miles into Kansas City and operation over Union Pacific rails from Council Bluffs to Omaha, the Missouri River formed the western boundary of the CM&StP. (“Milwaukee Road” as a name or nickname did not come into use until the late 1920s; “St. Paul Road” was sometimes used as a nickname, but the railroad’s advertising used the full name).

The Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway in 1893.

Poor’s Manual of the Railroads of the United States via Wikimedia Commons.

The battle over control of the Northern Pacific and the Burlington in 1901 made the Milwaukee Road aware that without its own route to the Pacific it would be at its competitors’ mercy. At the same time the Milwaukee Road was experiencing a change in its traffic from dominance by wheat to a more balanced mix of agricultural and industrial products. Arguments against extension westward included the possibility of the construction of the Panama Canal and the presence of strong competing railroads: Union Pacific, Northern Pacific, and Great Northern. Arguments for the extension banked heavily on the growth of traffic to and from the Pacific Northwest.

In 1901 the president of the Milwaukee Road dispatched an engineer west to estimate the cost of duplicating Northern Pacific’s line. His figure was $45 million. Such an expenditure required considerable thought; not until November 1905 did Milwaukee’s board of directors authorize construction of a line west to Tacoma and Seattle.

In 1905 and ’06 the Milwaukee Road incorporated subsidiaries in South Dakota, Montana, Idaho, and Washington. The Washington company was renamed the Chicago, Milwaukee & Puget Sound Railway, and it took over the other three companies in 1908. It was absorbed by the CM&StP in 1912.

The extension began with a bridge across the Missouri River at Mobridge, 3 miles upstream from Evarts, S.D. Roadbed and rails pushed out from several points into unpopulated territory. The work went quickly, and the road was open to Butte, Mont., in August 1908.

Unfortunately for the Milwaukee, the Pacific extension was much more expensive to build than the initial estimates (it jumped from $45 million in the 1901 survey to $60 million in 1905), eventually weighing down the company books with $257 million in debt and worse, the traffic estimates for the new line turned out to be wildly optimistic. The difficulties of operating steam locomotives across the extension in winter pushed the railway toward electrification as an efficiency and cost-saving move. Beginning in 1914, sections of the line were converted to overhead catenary power until a total of 645 route-miles were being operated with electric locomotives, reportedly saving the company over a million dollars per year.

A Milwaukee “Little Joe” electric locomotive hauling a freight train along the Pacific extension in 1941. The “Little Joe” locomotives were originally built for the Soviet Union in the late 1940s but the US government cancelled the export license as relations with the Soviets deteriorated and the Cold War escalated. The Milwaukee Road bought 12 of the 20 from General Electric for $1 million during the Korean War.

Wikimedia Commons.

Despite the savings through electrification, the Pacific extension drove the company into bankruptcy in 1925, re-emerging as the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad, but the new company also had to declare bankruptcy during the Great Depression. Trustees ran the railroad for ten years until renewed civilian traffic after World War 2 allowed normal operations to resume. As with most North American railroads, the good times didn’t last and by the late 1950s, the Milwaukee’s management were looking for a merger partner to help cut costs and shed unprofitable branch lines. Unlike the rival merger of of Northern Pacific, Great Northern, Burlington Route, and the Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway into Burlington Northern, the ICC blocked a merger between the Milwaukee Road and the Chicago and North Western. The ICC also blocked a later application for the Milwaukee to be included in the Union Pacific/Rock Island merger.

With declining business, deferred maintenance issues on most lines, and some self-induced financial issues caused by selling off rolling stock and leasing it back (which exacerbated car shortages leading to further reductions in business), the company had no funds to replace the failing “Little Joe” locomotives on the Pacific extension, so electrification was abandoned in 1974. George Drury sums up the mistakes that led to the end:

Over the decades, the road’s management had made too many wrong decisions: building the Pacific Extension, not electrifying between the two electrified portions, purchasing the line into Indiana, and in the 1960s choosing Flexivans (containers with separate wheels/bogies that required special flatcars) instead of conventional piggyback trailers.

After several money-losing years in the early 1970s, the Milwaukee voluntarily entered reorganization once again on December 19, 1977. The major result of the 1977 reorganization was the amputation of everything west of Miles City, Mont., to concentrate on what became known as the “Milwaukee II” system linking Chicago, Kansas City, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Duluth (on Burlington Northern rails from St. Paul), and Louisville (but no longer Omaha).

By 1983 the Milwaukee’s system consisted of the Chicago–Twin Cities main line; Chicago–Savanna–Kansas City; Chicago–Louisville (almost entirely on Conrail and Seaboard System rails), Milwaukee–Green Bay; New Lisbon–Tomahawk, Wis.; Savanna–La Crosse, along the west bank of the Mississippi; Marquette to Sheldon, Iowa, and Jackson, Minn.; Austin, Minn.–St. Paul; and St. Paul–Ortonville, Minn., plus a few branches.

Three roads vied for what remained of the Milwaukee: the Chicago & North Western, financially none too solid itself; Canadian National subsidiary Grand Trunk Western, with an eye toward creating a route between eastern and western Canada south of the Great Lakes; and Canadian Pacific subsidiary Soo Line.

January 7, 2021

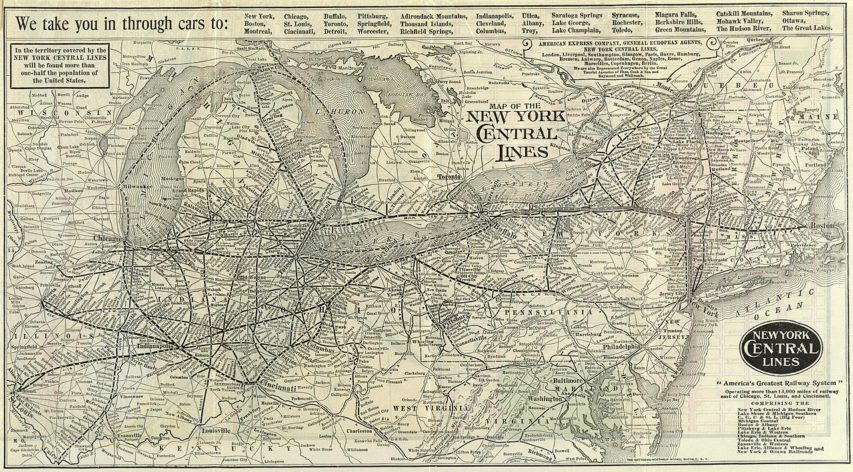

Fallen Flag — the New York Central System

This month’s Classic Trains fallen flag feature is the first part of the history of the New York Central System by George Drury. The New York Central was one of the biggest and most economically powerful American railways for over a century before the postwar boom turned into the economic disaster of the 1960s and 70s, as passengers switched from rail to road and plane and the decline of northeastern heavy industry and mining hit the established eastern railroads very hard:

This month’s Classic Trains fallen flag feature is the first part of the history of the New York Central System by George Drury. The New York Central was one of the biggest and most economically powerful American railways for over a century before the postwar boom turned into the economic disaster of the 1960s and 70s, as passengers switched from rail to road and plane and the decline of northeastern heavy industry and mining hit the established eastern railroads very hard:

The New York Central was a large railroad, and it had several subsidiaries whose identity remained strong, not so much in cars and locomotives carrying the old name but in local loyalties: If you lived in Detroit, you rode to Chicago on the Michigan Central, not the New York Central; through the Conrail era and even now, the line across Massachusetts is still known as “the Boston & Albany.”

The streamlined steam locomotive New York Central Hudson No.5344 “Commodore Vanderbilt”, leaving Chicago’s LaSalle Street station pulling the NYC’s premier passenger traing, the 20th Century Limited, 22 February 1935.

Photo originally copyrighted International News Photos (copyright not renewed) via Wikimedia CommonsThe system’s history is easier to digest in small pieces: first New York Central followed by its two major leased lines, Boston & Albany and Toledo & Ohio Central; then Michigan Central and Big Four (Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis). By the mid-1960s NYC owned 99.8 percent of the stock of Michigan Central and more than 97 percent of the stock of the Big Four. NYC leased both on Feb. 1, 1930, but they remained separate companies to avoid the complexities of merger.

In broad geographic terms, the NYC proper was everything east of Buffalo plus a line from Buffalo through Cleveland and Toledo to Chicago (the former Lake Shore & Michigan Southern). NYC included the Ohio Central Lines (Toledo through Columbus to and beyond Charleston, W.Va.) and the Boston & Albany (neatly defined by its name). The Michigan Central was a Buffalo–Detroit–Chicago line and everything in Michigan north of that. The Big Four was everything south of NYC’s Cleveland–Toledo–Chicago line other than the Ohio Central.

The New York Central System included several controlled railroads that did not accompany NYC into the Penn Central merger. The most important of these were (with the proportion of NYC ownership in the mid-1960s):

- Pittsburgh & Lake Erie (80 percent)

- Indiana Harbor Belt (NYC, 30 percent; Michigan Central, 30 percent; Chicago & North Western, 20 percent; and Milwaukee Road, 20 percent)

- Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo (NYC, 37 percent; MC, 22 percent; Canada Southern, 14 percent; and Canadian Pacific, 27 percent).

[…]

The New York & Harlem Railroad was incorporated in 1831 to build a line in Manhattan from 23rd Street north to 129th Street between Third and Eighth avenues (the railroad chose to follow Fourth Avenue). At first the railroad was primarily a horsecar system, but in 1840 the road’s charter was amended to allow it to build north toward Albany. In 1844 the rails reached White Plains and in January 1852 the New York & Harlem made connection with the Western Railroad (later Boston & Albany) at Chatham, N.Y., creating a New York–Albany rail route.

The towns along the Hudson River felt no need of a railroad, except during the winter when ice prevented navigation. Poughkeepsie interests organized the Hudson River Railroad in 1847. The railroad opened from a terminal on Manhattan’s west side all the way to East Albany. By then the road had leased the Troy & Greenbush, gaining access to a bridge over the Hudson at Troy. (A bridge at Albany was completed in 1866.)

By 1863 Cornelius Vanderbilt controlled the New York & Harlem and had a substantial interest in the Hudson River Railroad. In 1867 he obtained control of the New York Central, consolidating it with the Hudson River in 1869 to form the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad.

Vanderbilt wanted to build a magnificent terminal for the NYC&HR in New York. He chose as its site the corner of 42nd Street and Fourth Avenue on the New York & Harlem, the southerly limit of steam locomotive operation in Manhattan. Construction of Grand Central Depot began in 1869. The new depot was actually three separate stations serving the NYC&HR, the New York & Harlem, and the New Haven. Trains of the Hudson River line reached the New York & Harlem by means of a connecting track completed in 1871 along Spuyten Duyvil Creek and the Harlem River (they have since become a single waterway). That was the first of three Grand Centrals.

The Wikipedia page on the New York Central includes a good overview of the decline of the railway:

The New York Central, like many U.S. railroads, declined after the Second World War. Problems resurfaced that had plagued the railroad industry before the war, such as over-regulation by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), which severely regulated the rates charged by the railroad, along with continuing competition from automobiles. These problems were coupled with even more formidable forms of competition, such as airline service in the 1950s that began to deprive NYC of its long-distance passenger trade. The Interstate Highway Act of 1956 helped create a network of efficient roads for motor vehicle travel through the country, enticing more people to travel by car, as well as haul freight by truck. The 1959 opening of the Saint Lawrence Seaway adversely affected NYC freight business. Container shipments could now be directly shipped to ports along the Great Lakes, eliminating the railroads’ freight hauls between the east and the Midwest.

The NYC also carried a substantial tax burden from governments that saw rail infrastructure as a source of property tax revenues – taxes that were not imposed upon interstate highways. To make matters worse, most railroads, including the NYC, were saddled with a World War II-era tax of 15% on passenger fares, which remained until 1962, 17 years after the end of the war.

Robert R. Young: 1954–1958

In June 1954, management of the New York Central System lost a proxy fight in 1954 to Robert Ralph Young and the Alleghany Corporation he led.Alleghany Corporation was a real estate and railroad empire built by the Van Sweringen brothers of Cleveland in the 1920s that had controlled the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (C&O) and the Nickel Plate Road. It fell under the control of Young and financier Allan Price Kirby during the Great Depression.

R.R. Young was considered a railroad visionary, but found the New York Central in worse shape than he had imagined. Unable to keep his promises, Young was forced to suspend dividend payments in January 1958. He committed suicide later that month.

Alfred E. Perlman: 1958–1968

After Young’s suicide, his role in NYC management was assumed by Alfred E. Perlman, who had been working with the NYC under Young since 1954. Despite the dismal financial condition of the railroad, Perlman was able to streamline operations and save the company money. Starting in 1959, Perlman was able to reduce operating deficits by $7.7 million, which nominally raised NYC stock to $1.29 per share, producing dividends of an amount not seen since the end of the war. By 1964 he was able to reduce the NYC long-term debt by nearly $100 million, while reducing passenger deficits from $42 to $24.6 million.Perlman also enacted several modernization projects throughout the railroad. Notable was the use of Centralized Traffic Control (CTC) systems on many of the NYC lines, which reduced the four-track mainline to two tracks. He oversaw construction and/or modernization of many hump or classification yards, notably the $20-million Selkirk Yard which opened outside of Albany in 1966. Perlman also experimented with jet trains, creating a Budd RDC car (the M-497 Black Beetle) powered by two J47 jet engines stripped from a B-36 Peacemaker bomber as a solution to increasing car and airplane competition. The project did not leave the prototype stage.

Perlman’s cuts resulted in the curtailing of many of the railroad’s services; commuter lines around New York were particularly affected. In 1958–1959, service was suspended on the NYC’s Putnam Division in Westchester and Putnam counties, and the NYC abandoned its ferry service across the Hudson to Weehawken Terminal. This negatively impacted the railroad’s West Shore Line, which ran along the west bank of the Hudson River from Jersey City to Albany, which saw long-distance service to Albany discontinued in 1958 and commuter service between Jersey City and West Haverstraw, New York terminated in 1959. Ridding itself of most of its commuter service proved impossible due to the heavy use of these lines around metro New York, which government mandated the railroad still operate.

Many long-distance and regional-haul passenger trains were either discontinued or downgraded in service, with coaches replacing Pullman, parlor, and sleeping cars on routes in Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. The Empire Corridor between Albany and Buffalo saw service greatly reduced with service beyond Buffalo to Niagara Falls discontinued in 1961. On December 3, 1967, most of the great long-distance trains ended, including the famed Twentieth Century Limited. The railroad’s branch line service off the Empire Corridor in upstate New York was also gradually discontinued, the last being its Utica Branch between Utica and Lake Placid, in 1965. Many of the railroad’s great train stations in Rochester, Schenectady, and Albany were demolished or abandoned. Despite the savings these cuts created, it was apparent that if the railroad was to become solvent again, a more permanent solution was needed.

December 17, 2020

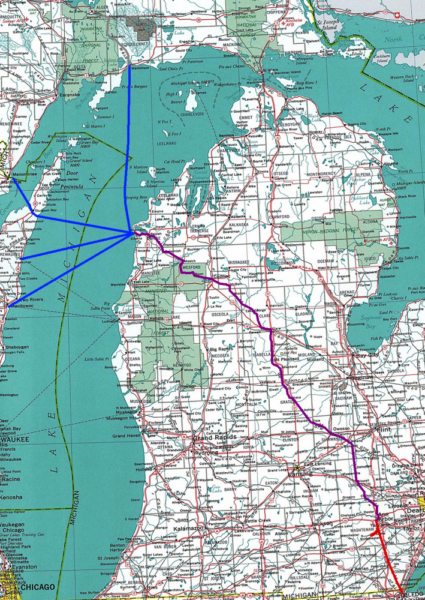

Fallen Flag — the Ann Arbor Railroad

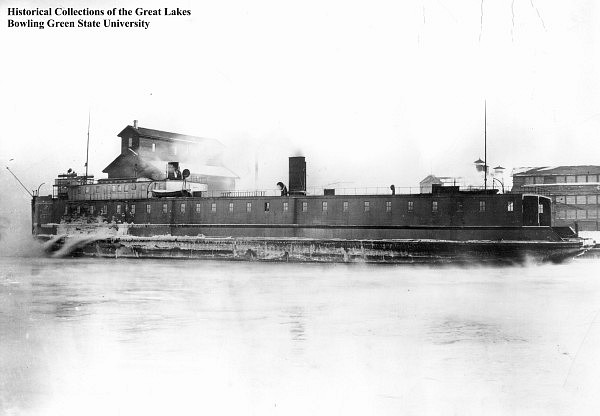

This month’s Classic Trains featured fallen flag is the Michigan-based Ann Arbor Railroad which operated rail services from Toledo, Ohio to Elberta and Frankfort, Michigan, along with lake ferry service across Lake Michigan to Manitowoc and Kewaunee, Wisconsin and Menominee and Manistique in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Robert I. Warrick provides an outline of the history of the line:

Ann Arbor No. 1, built in 1892 by Craig Shipbuilding Co. in Toledo, Ohio. She was destroyed in a fire on March 7, 1910 at Manitowoc, Wisconsin.

Photo from Bowling Green State University via Wikimedia Commons.

The Ann Arbor Railroad was as much a steamship line as a railroad. Built from Toledo, Ohio, northwest to Frankfort, Mich., it existed for one reason — to move freight in car ferries across Lake Michigan to bypass Chicago. From 1910 to 1968, “the Annie” operated 320 car ferry route-miles versus 292 miles of railroad. AA was at the forefront of car ferry design and innovation, from the first wooden-hulled vessels to the most advanced car ferry to ever sail Lake Michigan.

During the 1940s, up to six ferries made the round trip from Boat Landing, as AA called its yard in Elberta on the south side of Frankfort harbor, to two Wisconsin and two Michigan Upper Peninsula ports. The boats ran year-round on a tight schedule, timed to match with three pairs of scheduled Toledo freights, where AA interchanged with five trunk lines. Well-kept 2-8-2s powered those short, fast trains across AA’s rolling profile until 1950, when Alco FA2s took over.

[…]

The Eastern mergers of the 1960s ultimately doomed the old Ann Arbor. As planning for Penn Central went on, the Norfolk & Western merged with Wabash, Nickel Plate, and two smaller roads in 1964. N&W wanted no part of the Ann Arbor and its costly ferries, so AA was foisted off on DT&I, which was profitable by the 1960s.

With ICC approval, DT&I took over the Ann Arbor on August 31, 1963, and soon replaced the tired FA2s with 10 GP35s, riding on Alco trucks and painted in DT&I orange with large “Ann Arbor” lettering. DT&I’s GPs often mixed with the Annie’s.

DT&I had ferry Wabash refitted, changed her name to City of Green Bay, and loaned AA $2.5 million to rebuild Ann Arbor No. 7. The railroad renamed No. 7 Viking, lengthened it, installed four EMD 2,500 h.p. 567 diesels. But even with the bigger boats, capacity remained an issue as car sizes increased. AA was losing money. First the ferry route to Manistique, Mich. (and AA subsidiary Manistique & Lake Superior), was discontinued, then the one to Menominee, Mich.

Ann Arbor’s fate was sealed. A firm was hired to liquidate Pennsylvania Company assets, including AA and DT&I. Ann Arbor defaulted on the loan for the Viking on November 1, 1972, and filed for bankruptcy on October 15, 1973, leading to AA’s inclusion with other bankrupts in the Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973 that resulted in Conrail.

April 2, 2020

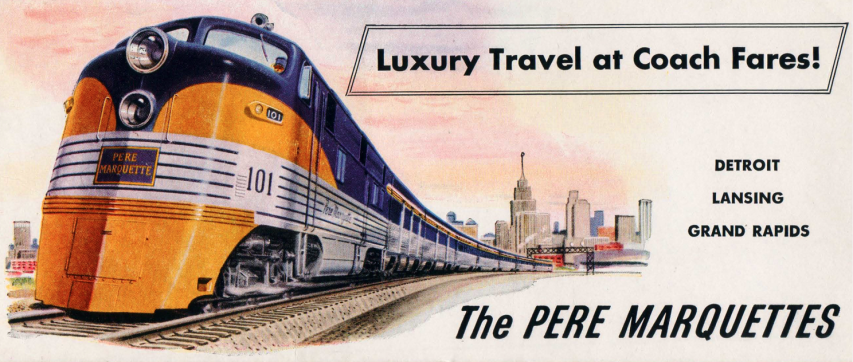

Fallen flag — the Pere Marquette Railway

This month’s fallen flag article for Classic Trains is the story of the Pere Marquette Railway by Kevin P. Keefe:

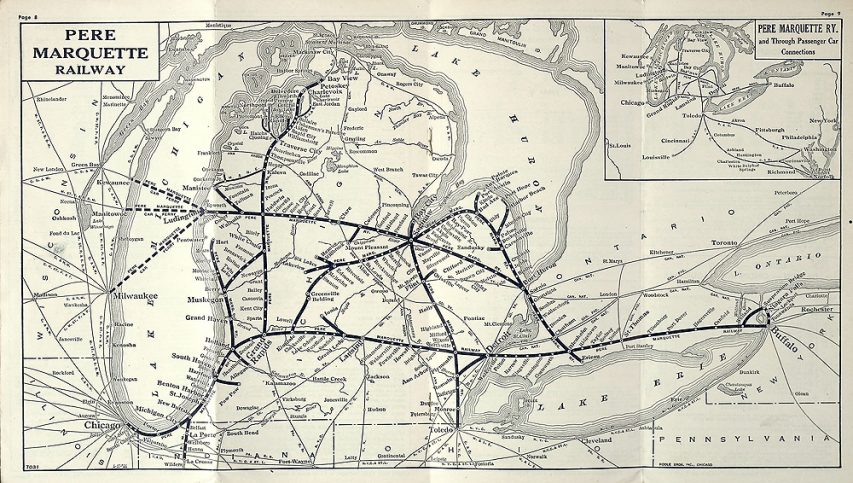

C&O’s formal acquisition of the Pere Marquette in 1947 did more than help usher in the postwar merger era; it also closed the book on a railroad with a colorful and quirky history. PM was created in 1900 by the consolidation of three roads: Flint & Pere Marquette; Detroit, Grand Rapids & Western; and Chicago & West Michigan. (The town of Pere Marquette; today we know the place as Ludington. Jacques Marquette, the French missionary and explorer, died and was buried here in 1675, and the name Pere Marquette had been given to the inlet lake off Lake Michigan, the river that feeds into it, and an 1847 community there.)

All three carriers had roots in the lumber industry, so the new Pere Marquette Railroad not only connected important Michigan cities, it also operated a branchline network covering much of the state’s Lower Peninsula. PM’s early corporate history was chaotic, marked by receivership and ownership changes. The Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton acquired PM in 1904 and for a time leased it to various parties, including the Erie Railroad. Thus did Baltimore & Ohio briefly control the PM through its ownership of the CH&D. When Pere Marquette came out of a receivership in 1907, it would be for only five years.

Those early, troublesome times, however, were marked by two strategic steps forward. One was the chartering of the Pere Marquette of Indiana, which built from New Buffalo, Michigan, southwest to Porter, Indiana, allowing PM to reach Chicago, via trackage rights on the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern (NYC). The second was the lease of the Lake Erie & Detroit River Railway, pushing PM eastward from Walkerville (Windsor), Ontario, to St. Thomas, thence to Suspension Bridge (Niagara Falls), New York, via rights on Michigan Central affiliate Canada Southern, and on to Buffalo on the NYC. Patched together as they were, these additions allowed PM to position itself as a Buffalo–Chicago bridge carrier.

In the ensuing years, the rectangular PM logo would largely disappear from view, although the road’s eventual 12 E7’s wore the script Pere Marquette train name, along with C&O identification, into the mid-1950s, thanks to equipment trust restrictions. PM’s three GE 70-tonners of 1947 were sold, but a few of its 16 EMD switchers (2 SW1’s of 1939 and ’42, 14 NW2’s of 1943–46) carried PM lettering into the 1960s, and C&O kept PM’s color pattern of yellow front-end bands with red pinstriping on a blue body on 11 more EMDs of 1948 that came fully lettered C&O: NW2’s 1850–1856 and E7’s 95–98.

As for the famous Berkshires, they, along with all of Pere Marquette’s steam locomotives, were retired by 1951. Eleven found a temporary reprieve on C&O’s Chesapeake District in Kentucky and West Virginia, but only for a few months. Two, 1223 and 1225, survived as display items in Michigan, and as a student at Michigan State University, I became involved with the restoration of the 1225, which today occasionally operates on excursions.

Perhaps it’s fitting that the Pere Marquette’s last equipment order as an independent railroad was in 1947 for six of EMD’s 1,500 h.p. BL2 “branchline” diesels, Nos. 80–85. Chosen to negotiate PM’s web of secondary lines — most of them rooted in the road’s origins as a logger — the homely diesels were as quirky and as singular as the PM itself. Pointedly, even though they sported the “speed striping” as found on the E7’s, the BL2’s were delivered in full “Chesapeake & Ohio” lettering.

Pere Marquette 1225, a Berkshire 2-8-4 steam locomotive, passes through Alma in March 2009.

Photo by Chelseyafoster via Wikimedia Commons.

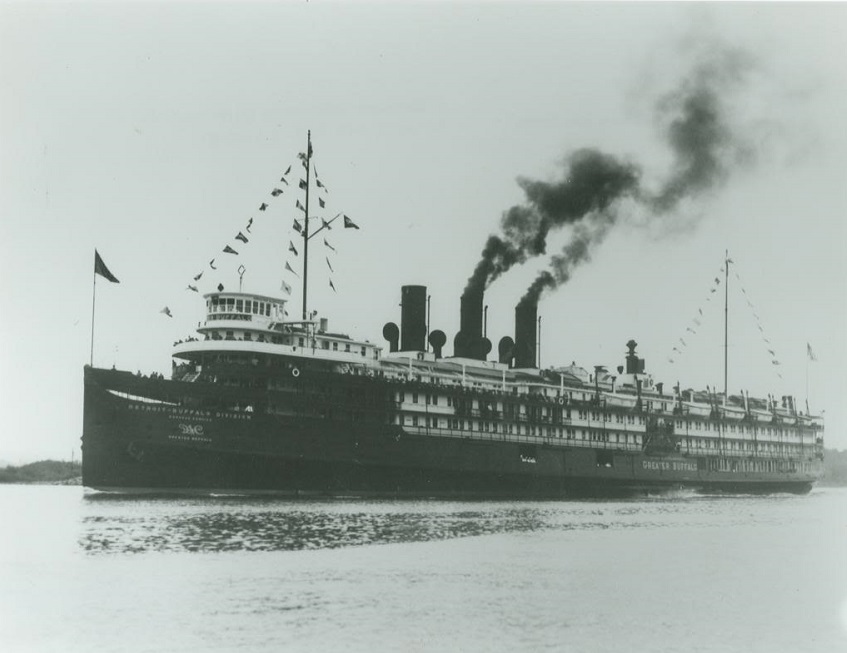

The Pere Marquette also had a maritime division and one of their ships had a disastrous voyage (via Wikipedia) 110 years ago:

The Pere Marquette operated a number of rail car ferries on the Detroit and St. Clair Rivers and on Lake Erie and Lake Michigan. The PM’s fleet of car ferries, which operated on Lake Michigan from Ludington, Michigan to Milwaukee, Kewaunee, and Manitowoc, Wisconsin, were an important transportation link avoiding the terminal and interchange delays around the southern tip of Lake Michigan and through Chicago. Their superintendent for over 30 years was William L. Mercereau.

Pere Marquette 18

On September 10, 1910, Pere Marquette 18 was bound for Milwaukee, Wisconsin, from Ludington, Michigan, with a load of 29 railroad freight cars and 62 persons. Near midnight, the vessel began to take on massive amounts of water. The captain dumped nine railroad cars into Lake Michigan, but this was no use — the ship was going down. The Pere Marquette 17, traveling nearby, picked up the distress call and sped to assist the foundering vessel. Soon after she arrived and she could come alongside, the Pere Marquette 18 sank with the loss of 28 lives; there were 33 survivors. Her wreck has yet to be located and is the largest unlocated wreck of the Great Lakes.

October 11, 2018

It’s all in the spin – “Another ‘human trafficking operation’ that wasn’t”

Elizabeth Nolan Brown on how to pitch a “human trafficking” police sweep that doesn’t actually uncover any human trafficking at all:

One hundred and twenty-three missing Michigan minors were found during a one-day “sex trafficking operation,” the New York Post reported yesterday. Similar statements showed up in other news headlines across national and international news. What the associated articles fail to mention for multiple paragraphs is that only three of the minors are even suspected of having been involved in prostitution.

Officials said the operation — a joint effort of the U.S. Marshals Service, the FBI, Michigan State Police, and multiple local Michigan police departments — identified three “possible sex-trafficking cases” among the 123 minors that were located on September 26, according to a press release.

What’s more, all but four of the “missing children” were not actually missing. In the remaining cases, minors were listed in a police database as missing but had since been found or returned home on their own. “Many were (homeschooled),” Lt. Michael Shaw told The Detroit News. “Some were runaways as well.”

The one-day “rescue” sweep was a long-time in the making, with police beforehand “investigating their whereabouts by visiting last known addresses, friend’s homes and schools.”

Nothing in the U.S. Marshals report on the operation makes mention of any arrested kidnappers, “traffickers,” or other adults involved in endangering or exploiting any of the missing minors that were identified. Which makes sense — very few missing children are actually abducted. And when runaway teens do engage in sex for money, the vast majority do not have “pimps.”

June 19, 2018

Detroit’s Michigan Central Station purchased by Ford

In Trains News Wire, Kevin P. Keefe rounds up the news from last week about the purchase of Detroit’s imposing former Michigan Central Station:

The abandoned Michigan Central Train Station, as seen from Roosevelt Park in Detroit.

Photo by Albert Duce, via Wikimedia Commons

The news this week that the Ford Motor Co. has purchased Detroit’s crumbling but historic Michigan Central Station indicates a happy ending for one of America’s most notoriously neglected big-city train stations.

Ford purchased the building from the Manuel Moroun family, billionaire owners of a trucking and logistics empire, which includes the Ambassador Bridge linking Detroit with Windsor, Canada. A purchase price for the station has not been disclosed.

A Ford spokesman said the company would announce detailed plans for the site at a June 19 press conference and open house. It is presumed the project will include renovation of the passenger terminal and its 18-story office building. At a press conference Monday, Matthew Moroun, heir to the Moroun fortune, said Ford’s “blue oval will adorn the building.”

[…]

In Michigan Central Station, Ford is acquiring one of railroading’s great architectural monuments. Two firms designed the 1913 station: St. Paul, Minn.-based Reed & Stem, of New York’s Grand Central Terminal fame; and New York-based Warren & Wetmore, known for such hotels as the Biltmore and Ritz-Carlton in Manhattan.

When the station opened, the Michigan Central was already a subsidiary of the New York Central, but a proud and independent one. With its 19th century roots in Boston’s financial aristocracy, the Michigan Central wanted to build monuments of its own. In a sprawling two-part series in the August and September 1978 issues of Trains Magazine, authors Garnet R. Cousins and Paul Maximuke called it “the proud symbol of a mighty railroad.”

The station was also unusual by virtue of its connection to the Detroit River Tunnel Co., which carried the Michigan Central main line beneath the Detroit River just a mile east of the station, linking the railroad with its Canada Southern affiliate. The tunnel opened in October 1910. The long grade necessary for the tunnel necessitated Michigan Central Station’s location more than a mile west of downtown Detroit at the corner of Vernor Highway and Michigan Avenue.

In its heyday, Michigan Central Station was as vital as any in the Midwest. In 1929, the station saw more than 90 arrivals and departures each day. Ultimately the depot could boast a number of famous NYC trains, including the Mercury, Wolverine, and, at the top, the daily Twilight Limited, originally an all-Pullman parlor-car train to Chicago. The station thrived through the postwar streamliner era.

November 5, 2013

Lake Michigan’s carrier fleet

I’d never heard of the US Navy’s carrier training ships that operated on Lake Michigan from 1942-45, so this link to a thread at Warbird Information Exchange from Roger Henry was of great interest:

This thread may give you a nice idea of what that exercise was all about. Many interesting images to study here and quite possibly of interest to those who are involved with the restoration of aircraft that have been recovered from the Lakes. I have also included a page from my dad’s logbook showing his 1st thru 8th carrier landings on the USS Wolverine in July 1944. Sources are the NMNA archives, Library of Congress photo archives, LIFE image archives.

This will be a large photo thread in a few parts so we’ll start with the two principal ships.

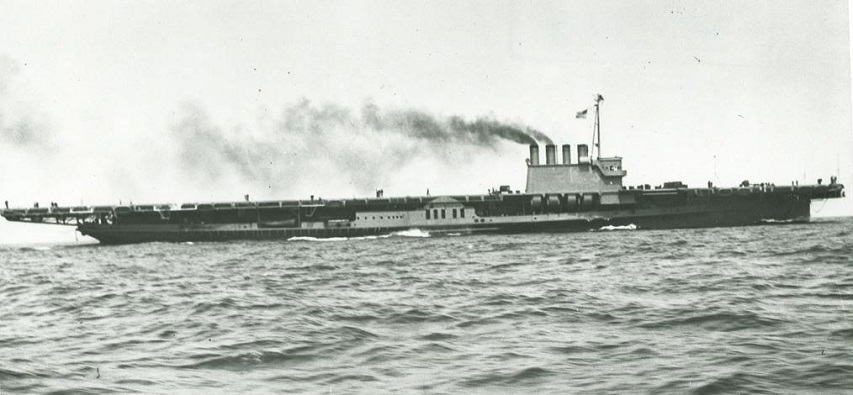

WIKI: USS Sable (IX-81) was a training ship of the United States Navy during World War II. Originally built as the Greater Buffalo, a sidewheel excursion steamer, she was converted in 1942 to a freshwater aircraft carrier to be used on the Great Lakes. She was used for advanced training for naval aviators in carrier takeoffs and landings. One aviator that trained upon the Sable was future president George H. W. Bush. Following World War II, Sable was decommissioned on 7 November 1945. She was sold for scrapping on 7 July 1948 to the H.H. Buncher Company.

I was initially surprised that both training carriers were converted side-paddle steamers … I’d have thought the extra costs in converting to propeller drive would make them less-than ideal conversion subjects — you can clearly see in the second image that they left the side-paddles in place, so the main cost of conversion was the construction of the flight deck and repositioning the smokestacks to the starboard side (no hangar deck, elevators, or catapults in evidence):

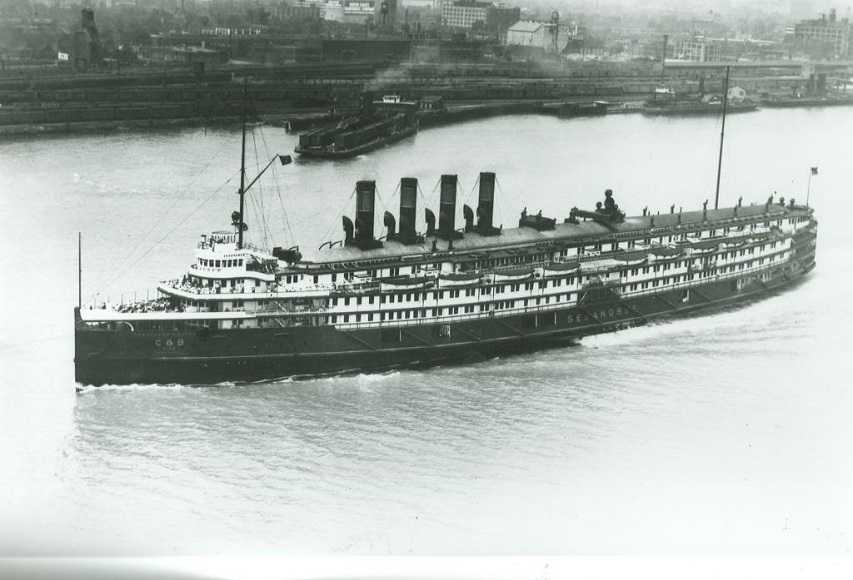

WIKI: USS Wolverine (IX-64) a side-wheel excursion steamer built in 1913—was originally named Seeandbee, a name based upon her owners’ company name, the Cleveland and Buffalo Transit Co.[4] She was constructed by the American Ship Building Company of Wyandotte, Michigan. The Navy acquired the sidewheeler on 12 March 1942 and designated her an unclassified miscellaneous auxiliary, IX-64. She was purchased by the Navy in March 1942 and conversion to a training aircraft carrier began on 6 May 1942.[5] The name Wolverine was approved on 2 August 1942 with the ship being commissioned on 12 August 1942.[5][6] Intended to operate on Lake Michigan, IX-64 received its name because the state of Michigan is known as the Wolverine State.

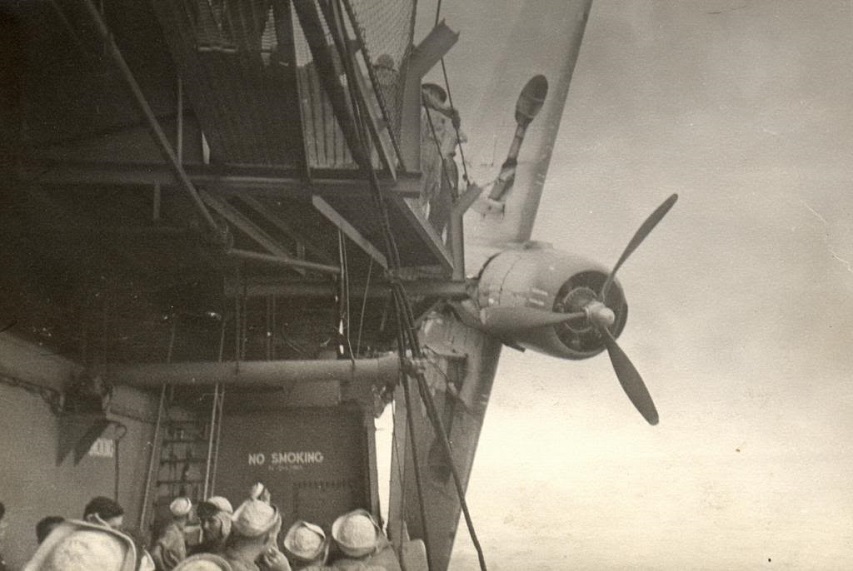

And given that almost all the pilots were still learning their trade — these were training ships, after all — there were more than a few mishaps:

July 27, 2013

Municipal bonds and the economic law of gravity

In the US, municipal bonds — bonds issued by city or other municipal governments — have been widely viewed as “safe” investments. Detroit may cause that view to change drastically. Reggie Middleton has been sounding the alarm for a few years:

Following up on my timely post “Here Come Those Municipal Defaults That Everyone Said Couldn’t Happen, Pt 2“, I comment on Meredith Whitney’s OpEd in the Financial Times. If you remember, she — like I — warned of municipal defaults years ago and was ridiculed for such. Ms. Whitney is quoted as saying:

“As jarring as the reality may be to accept, Detroit’s decision last week to declare bankruptcy should not be regarded as a one-off in the U.S. municipal market.” she said.

“There are five more towns like Detroit in Michigan alone. There are many more municipalities across the country in similar positions.”

“The bill for promises past is now so large for some cities and towns that it is crowding out money for the most basic of services — in the case of Detroit, it could not even afford to run its traffic lights,” she said.

“Will [lawmakers] side with taxpayers, unions or the municipal bondholders? If they back residents, money will be directed to underfunded public services at the expense of pensions and bondholders. If they side with the unions, social services will continue to be cut and the risk to bondholders will increase considerably. If they side with bondholders, social services and pensions are at risk.”

In the case of Detroit, elected officials, for the first time in a very long time, are siding with residents, Whitney said. This is a new precedent that boils down to the straightforward reality of the survival and sustainability of a town or city, she said.

“After decades of near-third-world conditions in the richest country in the world, the city finally stood up and said enough was enough,”

Well, this is the problem. Defaulting on revenue bonds where the underlying asset (ex. a housing project, utility, or infrastructure project) is not generating the sufficient cash flows is part and parcel of the risk of investing in said class of bonds. This is widely accepted and understood, which is likely why those bonds have a slightly higher yield.

For some obscene reason, defaulting on the general obligation bonds which purportedly carry the “full faith and credit’ of the municipality as a back stop is deemed as wholly different affair. The reason? Who the hell knows? This is a point I tried to drive home in the original “Here Come Those Municipal Defaults That Everyone Said Couldn’t Happen” article in 2011. Backing by the full faith and credit of a public entity does not make an investment risk free. To the contrary, if said entity is fundamentally insolvent, the investment is actually “riskful” as opposed to risk free.

Treating these bonds as unsecured in the bankruptcy is essentially the way to go. If you don’t want to do that, well you can still consider them backed by the full faith and credit of the insolvent municipality, which is essentially unsecured — and move on anyway — particularly as many potential collateral assets of value would have likely been encumbered by agreements with a little more prejudicial foresight.

October 25, 2012

A contrarian view of the proposed Detroit-Windsor bridge

Terence Corcoran points out that the proposed new bridge connecting Detroit and Windsor is not quite the simple story of Canadian generosity to cash-strapped Michigan:

In this view, Mr. Harper as Captain Canada had vanquished not only the state of Michigan and its governor, Rick Snyder. He had also declared war on the real battle target, the private corporation that controls the other Detroit-to-Windsor crossing, the Ambassador Bridge owned and controlled by the Moroun family, headed by 83-year-old billionaire Manuel Moroun.

Mr. Moroun, whose family has owned the bridge since the late 1970s — maintaining it and collecting all tolls — is portrayed as an influence-buying Tea Party capitalist who seeks tax breaks to prosper, a monopolist who wants to keep out competition, a symbol of all that is wrong with America’s special-interest dominated governments. Mr. Harper and Canada stand as principled, influence-free promoters of international trade, commerce and the public good.

It takes a lot of ideological twisting to reach that conclusion, especially for Conservatives who portray Mr. Harper as the economic good guy — despite all evidence to the contrary that Mr. Harper is the heavy-handed statist attempting to cripple a private entrepreneur. What Mr. Harper is really doing is using government power to do what Canadian governments have wanted to do for at least five decades: thwart the private ownership — and if possible take control — of the Ambassador Bridge.

[. . .]

So Mr. Harper, by moving in to fund a competing bridge using taxpayers’ dollars, is re-enacting the Trudeau policy, using more direct methods. Ottawa will pay to build a second bridge, potentially driving the Moroun family out of business.

Being a billionaire, Manuel Moroun isn’t a sympathetic figure. He is described, among other things, as being a fake capitalist, a rent-seeking monopolist who does not want to face competition. It’s a charge that belittles Mr. Moroun and elevates the dubious intentions of the government. When a foreign national government shows up on your door, with the support of the governor of your state and likely the president of the United States, to announce that “We’re from the government and were here to compete with you,” Mr. Moroun has good reason to run to the courts and the political process.

For doing so, Mr. Moroun has been described as litigious, a wealthy manipulator and a purchaser of political favours. When it comes to manipulation, however, it’s hard to beat Ottawa and the massed forces of special-interest industries, unions and government bureaucrats who have joined to promote and build a new bridge at government expense.

October 24, 2012

Persuading Michigan voters to refuse a new free bridge to Canada

The announcement back in June must have appeared too good to be true: a new bridge between Detroit, Michigan and Windsor, Ontario to be completely funded by Canada. Michigan voters are being urged to refuse the deal:

Canada, understand, has agreed to pay for the bridge in full, including liabilities — and potential cost overruns — under an agreement that was about a decade-in-the-making and officially announced to much fanfare, at least on the Canadian side of the border, by Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Michigan Governor Rick Snyder in Windsor/Detroit in mid-June.

For Michigan, it is a slam-dunk arrangement. As Mr. Norton told one audience: ‘‘If this proves to be a dumb financial decision, it’s on us, not on you.’’

It’s a free bridge, a vital new piece of publicly owned infrastructure — for both countries — and yet one that is in grave danger of being demolished before construction even begins when Michigan voters head to the polls for a ballot initiative attached to the Nov. 6 elections.

[. . .]

Manuel (Matty) Moroun, an 85-year-old self-made billionaire who owns the 83-year-old Ambassador Bridge, is Cynic-in-Chief. The Ambassador is currently the only transport truck-bearing bridge in town. Twenty-five percent of Canadian-American trade, representing about $120-billion, flows across it each year.

It is a perfect monopoly for the Moroun family, a golden goose that just keeps on laying eggs, putting upwards of $80-million a year in tolls, duty free gas and shopping sales in their pockets. Allowing a Canadian-financed competitor into the ring without a fight isn’t an option.

October 1, 2012

Michigan’s unions battle for a veto right over state law

In the Wall Street Journal, Shikha Dalmia looks at a proposed constitutional amendment in Michigan which would give unions a huge veto power over state law:

The Michigan Supreme Court recently approved the placement of a proposed constitutional amendment on the November ballot. If passed by voters, the so-called Protect Our Jobs amendment would give public-employee unions a potent new tool to challenge any laws — past, present or future — that limit their benefits or collective-bargaining powers. It would also bar Michigan from becoming a right-to-work state in which mandatory union dues are not a condition of employment. The budget implications are dire.

[. . .]

The amendment says that no “existing or future laws shall abridge, impair or limit” the collective-bargaining rights of Michigan workers. That may sound innocuous, but according to Patrick Wright of the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, the amendment would hand a broad mandate to unions to challenge virtually any law they don’t like.

[. . .]

The ballot initiative states that it would “override state laws that regulate hours and conditions of employment to the extent that those laws conflict with collective bargaining agreements.” In other words, collective-bargaining agreements negotiated behind closed doors would trump the legislature — a breathtaking power grab that would turn unions into a super legislature.

Perhaps the biggest upside for unions is that the proposal would prohibit Michigan from becoming a right-to-work state. Regaining its competitive position with respect to the 23 right-to-work states that have become attractive to manufacturers, even auto makers, would be unlikely. Rather, labor would get a field-tested strategy for scrapping those states’ right-to-work laws with ballot referendums.