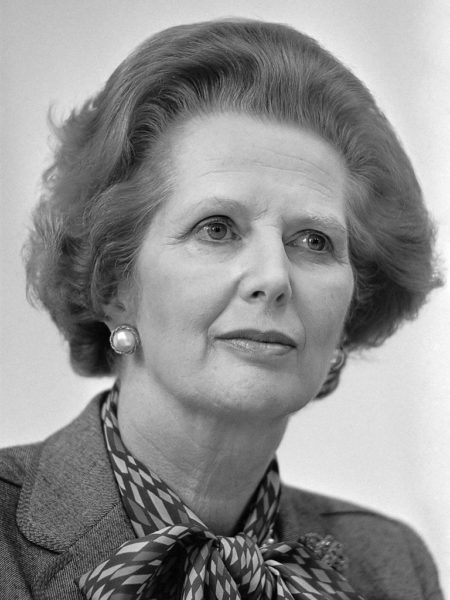

I know I’m supposed to hate Margaret Thatcher. I know that someone with my politics is meant to detest her as a union-busting, milk-snatching, women’s-lib-baiting, Belgrano-sinking, Section-28-devising, society-destroying nightmare. I know that when Gillian Anderson was cast as Thatcher in series four of The Crown, I should have played up a shudder of disgust at Gillian Anderson, who is good, playing Thatcher, who is bad.

But here’s the thing: I don’t hate Thatcher. It’s not that I’m a huge fan of her legacy or anything (although anyone who thinks that industrial relations were doing fine before her or that the Falklands were some kind of unjustified expedition is clearly a fantasist), it simply doesn’t matter whether I like her or not because she is just too interesting.

Thatcher wasn’t the first woman to lead a country, but unlike her predecessors, Indira Gandhi in India or Isabel Martínez de Perón in Argentina, she didn’t arrive sanctified by a political dynasty. She was, as Prince Phillip snobbily points out to the Queen in The Crown, a grocer’s daughter. In real life, such condescension came strongly from the Left. The Blow Monkeys, one of the bands involved in the Red Wedge tour to support Labour, released an album called She was only a Grocer’s Daughter in 1987; and even though several pop songs fantasised about her death, that never seemed quite as ugly as supposed defenders of the working class announcing that Thatcher was just too common to rule.

Sarah Ditum, “How Thatcher rejected feminism”, UnHerd, 2020-11-15.

February 24, 2021

QotD: Margaret Thatcher

August 26, 2020

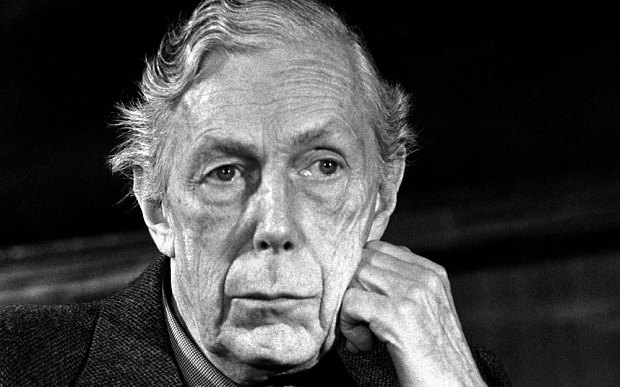

Sir Anthony Blunt, the “Fourth Man”

In The Critic, David Herman reviews a new book on the unmasking of Soviet spy … and close associate of the Royal family, Sir Anthony Blunt by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in 1979:

Anthony Blunt (1907-1983), was the “Fourth Man” in the Cambridge spy ring that supplied the Soviets with secret documents from within Britain’s WW2 intelligence services.

In November 1979, the newly elected Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, named Professor Sir Anthony Blunt, one of the most distinguished art historians in post-war Britain, as the “Fourth Man”, one of the traitors known as the “Cambridge Spies”, a group of spies working for the Soviet Union from the 1930s to at least the early 1950s. Mrs. Thatcher did not pull her punches. She regarded Blunt’s behaviour as “contemptible and repugnant”, and she was appalled by the evidence of treason and treachery at the heart of the British establishment.

What set Blunt apart from the others – Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean and Kim Philby – was his distinguished academic career. Blunt was professor of art history at the University of London, director of the Courtauld Institute of Art and Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures. He was related to the Queen Mother. His students included such famous figures as Anita Brookner, Sir Nicholas Serota, Sir Neil Macgregor and Sir Alan Bowness. He also passed 1,771 documents to his Soviet spymasters during the war while working for MI5. For some of this time, the Soviet Union was a foreign enemy, allied to Nazi Germany.

The mix of homosexuality, 1930s Cambridge and treason, the scholar and the spy, made a compelling story and Blunt has been the subject of a famous essay in The New Yorker by George Steiner (“The Cleric of Treason”, 8 December, 1980), plays by Dennis Potter (Blade on the Feather, 1980), Alan Bennett (A Question of Attribution, 1988) and a novel by John Banville (The Untouchable, 1997). More recently, he has turned up in the third season of The Crown (2019), played by Samuel West. Had Alex Jennings not already played the Duke of Windsor in earlier series of The Crown, he would have been perfect casting.

After Mrs. Thatcher’s revelations in the House of Commons, Blunt was immediately stripped of his knighthood and he was subsequently forced to resign his Honorary Fellowship at Trinity College, Cambridge. The University of London, however, did not take away his Emeritus Professorship and the French government did not strip him of his Legion of Honour. There could be no criminal proceedings against Blunt because in 1964 he had only admitted his guilt in exchange for guaranteed immunity for any subsequent prosecution for the rest of his life.

The question then arose how should the British Academy respond? Blunt had been a Fellow for almost twenty years. He had served as a Vice-President and was talked of as a possible future President.

Almost immediately lines were drawn and leading figures like the historians John H. Plumb and A.J.P. Taylor threatened to resign from the Academy. It was a spectacular bunfight and the press had a wonderful time.

March 8, 2020

Britain’s Post-WWII Naval Decline

Sal Viscuso

Published 1 Dec 2013Max Hastings describes the declining British post-WWII role in global affairs.

February 10, 2020

The coup that toppled Margaret Thatcher

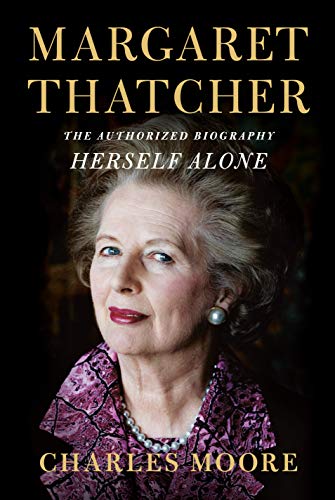

Charles Moore published the third volume of his Thatcher biography last year (I’ve read the first two volumes, but not the final one). In Quillette, Johan Wennström reviews the book:

This November will mark 30 years since former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher left office. After she had narrowly failed to secure an outright win in a 1990 leadership contest triggered by a challenge from Michael Heseltine, her former defense secretary, the majority of Thatcher’s Conservative cabinet colleagues withdrew their support and forced her departure following what she described as “eleven-and-a-half wonderful years.”

For Thatcher, the “coup,” as she referred to the events of 1990, had been unexpected. But as journalist Charles Moore explains in the third and final volume of his authorized Thatcher biography, Herself Alone (2019), the writing had been on the wall for some time. Thatcher’s style, which some considered abrasive, had turned senior figures against her. And many younger party members believed that if the party were to win a fourth consecutive election victory, in 1991 or 1992, it should be under a new standard-bearer (who turned out to be John Major).

An important underlying factor was the long-standing policy conflict regarding the European Community (or the EC as the European Union was then known), which pitted Thatcher against many in her own government, as well as against continental European leaders and George H. W. Bush’s White House. She was perceived as a “Cold Warrior” who was overly cautious in regard to the future of Europe, especially the project of European political and economic integration.

To some modern observers, that criticism of Thatcher remains apt. In a recently published book on international relations authored by former Swedish Prime Minister Carl Bildt, The Age of Disorder (Den nya oredans tid, 2019), Thatcher’s reluctance to endorse a speedy German reunification is attributed to her obsolete anxieties regarding “the dangers of a strong Germany.”

Moore’s latest volume, which focuses extensively on Thatcher’s views about Europe, shows her in a more nuanced light. In some ways, in fact, she was actually ahead of her time. And some of the current problems facing Europe, and the West more generally, might have been mitigated had her opinions been given a more generous audience.

Unfortunately, I don’t have the money for new hardcover books these days so I’ll have to wait until this volume gets a paperback edition or [shudder] get a library card and wait for it to show up at the local library.

June 8, 2019

QotD: Labour’s celebration at Thatcher’s death

A few hours after Margaret Thatcher’s death on Monday, the snarling deadbeats of the British underclass were gleefully rampaging through the streets of Brixton in South London, scaling the marquee of the local fleapit and hanging a banner announcing “THE BITCH IS DEAD”. Amazingly, they managed to spell all four words correctly. By Friday, “Ding Dong! The Witch Is Dead”, from The Wizard of Oz, was the Number One download at Amazon UK.

Mrs Thatcher would have enjoyed all this. Her former speechwriter John O’Sullivan recalls how, some years after leaving office, she arrived to address a small group at an English seaside resort to be greeted by enraged lefties chanting “Thatcher Thatcher Thatcher! Fascist fascist fascist!” She turned to her aide and cooed, “Oh, doesn’t it make you feel nostalgic?” She was said to be delighted to hear that a concession stand at last year’s Trades Union Congress was doing a brisk business in “Thatcher Death Party Packs” – almost a quarter-century after her departure from office.

Of course, it would have been asking too much of Britain’s torpid left to rouse themselves to do anything more than sing a few songs and smash a few windows. In The Wizard of Oz, the witch is struck down at the height of her powers by Dorothy’s shack descending from Kansas to relieve the Munchkins of their torments. By comparison, Britain’s Moochkins were unable to bring the house down: Mrs Thatcher died in her bed at the Ritz at a grand old age. Useless as they are, British socialists were at one point capable of writing their own anti-Thatcher singalongs rather than lazily appropriating Judy Garland blockbusters from MGM’s back catalogue. I recall in the late Eighties being at the National Theatre in London and watching the crowd go wild over Adrian Mitchell’s showstopper, “F**k-Off Friday”, a song about union workers getting their redundancy notices at the end of the week, culminating with the lines:

I can’t wait for That great day when F**k-Off Friday

Comes to Number Ten.You should have heard the cheers.

Mark Steyn, “The Uncowardly Lioness”, SteynOnline.com, 2019-05-05.

January 2, 2019

In non-breaking, non-news … politicians lie

Hector Dummond explains why what might seem like a shocking revelation from a former Thatcher MP isn’t even getting a raised eyebrow from the British media:

In a highly revealing article former MP Matthew Parris admits that the Conservative Party would often lie so that it could do what it wanted. And when it didn’t lie it fudged and avoided issues in order to prevent the ‘people’ having any say in the country’s governance:

our challenge was to find ways of ducking the issue. Once I became an MP, I did so by voting for the principle and against the practice. This subversion of democracy (in Theresa May’s phrase) caused me embarrassment, but not a second’s guilt. Sod democracy: hanging was wrong …

Among ourselves we talked cheerfully about subterfuge. The Britain of 1979 and 1983 most emphatically did not vote for a massive confrontation with the coal miners. We made sure the electorate was never asked.

These candid admissions have been completely ignored by the media. One reason they’ve been ignored is, of course, that most people have come to work this out for themselves, so Parris isn’t telling us anything we don’t already know. But surely hearing it from the horse’s mouth has great value? Why hasn’t the media splashed on this? Why haven’t Parris’s old enemies in the Labour party made hay with it?

The main reason is that most of the media, and virtually all the Labour party, is on his side over this. Even newspapers like the Guardian. You might think the Guardian would be the natural enemy of a former Tory MP, especially one who worked with Thatcher, and certainly on some issues they will regard Parris as an enemy, but the fact is that the Guardian wants government to be free of restraint by the people, because its vision of the state involves a leftist government getting into power, imposing its own ideology onto society and removing the power for the people to have a democratic say from most areas of life. So it can hardly criticise Parris for having done what it longs to do. It doesn’t want to bring about anything that might lessen the freedom government currently has to ignore the voter.

January 26, 2018

QotD: Britain’s boozy parliamentarians

It is Wright’s contention [in his book Order! Order!] that alcohol has as many benefits as it does drawbacks. Not only does it help loosen ties and tongues it also boosts confidence and dilutes stress. Most prime ministers drank, many to excess. Herbert Asquith went by the nickname “Squiffy Asquith” and regularly appeared in the Commons three sheets to the wind. Margaret Thatcher did her best to promote the whisky industry, the uncapping of a bottle of Bell’s marking the end of the working day. She believed that whisky rather than gin was good for you because “it will give you energy”, which I fear could be a hard fact to prove scientifically.

Tony Blair, whose reign ushered in an era of 24-hour drinking, thought his relatively modest drinking was getting out of control because he calculated it exceeded the government’s weekly recommended limit. This did not impress Dr John Reid, Bellshill’s finest, who once drank like a navvy. “Where I come from,” Reid told GMTV, “a gin and tonic, two glasses of wine, you wouldn’t give that to a budgie.” Blair, of course, did not have to look further than next door to find an explanation why his consumption increased over the years. Gordon Brown, his nemesis, was fond of Champagne – Möet & Chandon no less – which he did not nurse but washed down in a gulp. “He was like the cookie monster,” recalled one aide. “Down in one, whoosh!” Drinking is of course one of those areas in which we Scots have long punched above our weight and Wright’s pages are replete with examples of intoxicated Jocks carousing nights away and causing mayhem. Former Labour leader John Smith was one such. Occasionally I encountered him on the overnight train that carried Scottish MPs home from Westminster on a Thursday night. Known as “the sleeper of death”, it was a mobile pub that never closed until it reached Waverley, whereupon politicians were disgorged red-eyed and pie-eyed among bemused early morning commuters.

Alan Taylor, “Lush tales of our political classes’ drinking exploits”, The National, 2016-06-20.

August 9, 2017

The Falklands War – A War for Lost Glory I THE COLD WAR

Published on 1 Jul 2015

The Falklands War was based on an old colonial struggle between two former world powers. When the military Junta in Argentina decided to claim the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic they didn’t reckon with Great Britain’s Iron Lady Margaret Thatcher. The British Prime Minister unleashed full scale invasion. The Royal Navy and the British Army landed and ultimately took the capital Port Stanley. The Argentine Army surrendered shortly after that.

October 10, 2016

British “One Nation Conservatism”

Sean Gabb on the “choices” available to a theoretical British voter who might still pine for a smaller and less intrusive central government:

The truth is that, since the 1960s, Conservative and Labour Governments have alternated. In this time, with the partial exception of the first Thatcher term – and she did consider banning dildoes in 1983 – the burden of state interference has grown, if with occasional changes of direction. In this time, with the exception of John Major’s second term, the tax burden has stayed about the same as a percentage of gross domestic product. I cannot remember if Roy Jenkins or Gordon Brown managed to balance the budget in any particular year. But I do know that George Osborn never managed it, or tried to manage it, before he was thrown into the street. Whether the politicians promised free markets or intervention, what was delivered has been about the same.

A longer answer is to draw attention to the low quality of political debate in this country. It seems to be assumed that there is a continuum of economic policy that stretches between the low tax corporatism of the Adam Smith Institute (“the libertarian right”) and whatever Jeremy Corbyn means by socialism. So far as Mrs May has rejected the first, she must be drifting towards the second. Leave aside the distinction, already made, between what politicians say and what they do. What the Prime Minister was discussing appears to have been One Nation Conservatism, updated for the present age.

Because it has never had a Karl Marx or a Murray Rothbard, this doctrine lacks a canonic expression. However, it can be loosely summarised in three propositions:

First, our nation is a kind of family. Its members are connected by ties of common history and language, and largely by common descent. We have a claim on our young men to risk their lives in legitimate wars of defence. We have other claims on each other that go beyond the contractual.

Second, the happiness and wealth and power of our nation require a firm respect for property rights and civil rights. It is one of the functions of microeconomic analysis to show how a respect of property rights is to the common benefit. The less doctrinaire forms of libertarianism show the benefit to a nation of leaving people alone in their private lives.

Third, the boundaries between these first two are to be defined and fixed by a respect for the mass of tradition that has come down to us from the middle ages. Tradition is not a changeless thing, and, if there is to be a rebuttable presumption in favour of what is settled, every generation must handle its inheritance with some regard to present convenience.

The weakness of the One Nation Conservatives Margaret Thatcher squashed lay in their misunderstanding of economics. After the 1930s, they had trusted too much in state direction of the economy. But, rightly understood, the doctrine does seem to express what most of us want. If that is what the Prime Minister is now promising to deliver, and if that is what she does in part deliver, I have no reasonable doubt that she and her successors will be in office as far ahead as the mind can track.

April 3, 2016

Terry Teachout on the first two volumes of the authorized Thatcher biography

I read the first volume of Charles Moore’s authorized biography and I was impressed. I’m halfway through the second volume and I’m not enjoying it quite as much as the first. I think that’s a combination of the first volume covering the era I was most interested in (the 1960s and 70s, and the Falklands War) and the second volume covering a lot more of the domestic intricacies of British politics during the 1980s (an “inside baseball” view which I don’t find all that compelling). Terry Teachout didn’t bog down in the middle of volume two, and reports that he’s very impressed with Moore’s work:

Forgive the cliché, but I couldn’t put either book down. I stayed up far too late two nights in a row in order to finish them both — and I’m by no means addicted to political biographies, regardless of subject.

A quarter-century after she left office, Thatcher remains one of the most polarizing figures in postwar history. Because of this, I don’t doubt that many people will have no interest whatsoever in reading a multi-volume biography of her, least of all one whose tone is fundamentally sympathetic. That, however, would be a mistake. Not only does Moore go out of his way to portray Thatcher objectively, but Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography is by any conceivable standard a major achievement, not least for the straightforward, beautifully self-effacing style in which it is written. It is, quite simply, a pleasure to read. Yes, it’s detailed, at times forbiddingly so, but it is, after all, an “official” life, and the level of detail means that you don’t have to know anything about the specific events discussed in the book to be able to understand at all times what Moore is talking about. I confess to having done some skipping, especially in the second volume, but that’s because I expect to return to Margaret Thatcher at least once more in years to come.

One way that Moore leavens the loaf is by being witty, though never obtrusively so. His “jokes” are all bone-dry, and not a few of them consist of merely telling the truth, the best possible way of being funny. […]

He also conveys Thatcher’s exceedingly strong, often headstrong personality with perfect clarity and perfect honesty (or so, at any rate, it seems from a distance). At the same time, he puts that personality in perspective. It is impossible to read far in Margaret Thatcher without realizing that no small part of what made more than a few of Thatcher’s Tory colleagues refer to her as “TBW,” a universally understood acronym for “That Bloody Woman,” was the mere fact that she was a woman — and a middle-class woman to boot. Sexual chauvinism and social snobbery worked against her from the start, not merely from the right but from the left as well (Moore provides ample corroborating evidence of the well-known fact that there is no snob like an intellectual snob). That she prevailed for so long is a tribute to the sheer force of her character. That she was finally booted from office by her fellow Tories says at least as much about them as it does about her.

March 19, 2015

Thirty years on, what was the impact of the Miners’ strike in Britain?

Frank Furedi points out six ways that Britain’s political scene has changed as a result of the year-long miners’ strike:

To defeat the National Union of Miners, UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher and her Conservative government had to use almost every available resource, including the mass mobilisation of the police. The Miners’ Strike became the defining event of British politics in the 1980s. And in retrospect, it’s clear that it was the last class-focused dispute of its kind.

Over the past three decades, the political climate, culture and institutions that served as the background for the Miners’ Strike have fundamentally altered. Here are six things that changed enormously in the wake of that industrial conflict.

1) The defeat of the Miners’ Strike signalled the end of the era of militant trade unions

[…]

2) The demise of the British labour movement was paralleled by the decline of the left

The Labour Party has survived the post-1985 tumult, yes, but only by reinventing itself as the party of the middle-class, public-sector professional. Thanks to the vagaries of the electoral system, Labour can still have MPs in many of its traditional working-class seats. The decline of labourism also coincided with the implosion of the Stalinist communist movement and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

[…]

3) Paradoxically, the demise of the left has not benefited the right

Thatcherism, which was very much the dominant force during the Miners’ Strike, has lost its authority. Today’s so-called Conservatives regard Thatcher as an embarrassment and self-consciously distance themselves from her legacy. So defensive is the right today that it continually protests that it is no longer a ‘toxic brand’.

October 7, 2014

QotD: The Blue Tribe’s reaction to two famous deaths

The worst reaction I’ve ever gotten to a blog post was when I wrote about the death of Osama bin Laden. I’ve written all sorts of stuff about race and gender and politics and whatever, but that was the worst.

I didn’t come out and say I was happy he was dead. But some people interpreted it that way, and there followed a bunch of comments and emails and Facebook messages about how could I possibly be happy about the death of another human being, even if he was a bad person? Everyone, even Osama, is a human being, and we should never rejoice in the death of a fellow man. One commenter came out and said:

I’m surprised at your reaction. As far as people I casually stalk on the internet (ie, LJ and Facebook), you are the first out of the “intelligent, reasoned and thoughtful” group to be uncomplicatedly happy about this development and not to be, say, disgusted at the reactions of the other 90% or so.

This commenter was right. Of the “intelligent, reasoned, and thoughtful” people I knew, the overwhelming emotion was conspicuous disgust that other people could be happy about his death. I hastily backtracked and said I wasn’t happy per se, just surprised and relieved that all of this was finally behind us.

And I genuinely believed that day that I had found some unexpected good in people – that everyone I knew was so humane and compassionate that they were unable to rejoice even in the death of someone who hated them and everything they stood for.

Then a few years later, Margaret Thatcher died. And on my Facebook wall – made of these same “intelligent, reasoned, and thoughtful” people – the most common response was to quote some portion of the song “Ding Dong, The Witch Is Dead”. Another popular response was to link the videos of British people spontaneously throwing parties in the street, with comments like “I wish I was there so I could join in”. From this exact same group of people, not a single expression of disgust or a “c’mon, guys, we’re all human beings here.”

I gently pointed this out at the time, and mostly got a bunch of “yeah, so what?”, combined with links to an article claiming that “the demand for respectful silence in the wake of a public figure’s death is not just misguided but dangerous”.

And that was when something clicked for me.

You can talk all you want about Islamophobia, but my friend’s “intelligent, reasoned, and thoughtful people” – her name for the Blue Tribe – can’t get together enough energy to really hate Osama, let alone Muslims in general. We understand that what he did was bad, but it didn’t anger us personally. When he died, we were able to very rationally apply our better nature and our Far Mode beliefs about how it’s never right to be happy about anyone else’s death.

On the other hand, that same group absolutely loathed Thatcher. Most of us (though not all) can agree, if the question is posed explicitly, that Osama was a worse person than Thatcher. But in terms of actual gut feeling? Osama provokes a snap judgment of “flawed human being”, Thatcher a snap judgment of “scum”.

[…]

And my hypothesis, stated plainly, is that if you’re part of the Blue Tribe, then your outgroup isn’t al-Qaeda, or Muslims, or blacks, or gays, or transpeople, or Jews, or atheists – it’s the Red Tribe.

Scott Alexander, “I Can Tolerate Anything Except The Outgroup”, Slate Star Codex, 2014-09-30.

March 14, 2014

Iain Martin on the three phases of Tony Benn’s political career

The death of Tony Benn was announced this morning, and the Telegraph‘s Iain Martin says that Benn’s political trajectory had three distinct phases:

The BBC‘s James Landale described it well this morning only minutes after the death of Tony Benn was announced. There were, he told the Today programme, three phases of Tony Benn the public figure. That is right, and in the second phase Benn almost destroyed the Labour Party. His death — or his reinvention as a national treasure from the late 1980s onwards — doesn’t alter that reality.

In the 1950s and 1960s Benn was part of Labour’s supposed wave of the future, serving in Wilson’s governments and embodying the technocratic approach that was going to forge a modern Britain in the “white heat of technology”. It didn’t work out like that.

[…]

But it is when Labour found itself out of power in 1979 that Benn the socialist preacher applied his considerable talents — his gift for public speaking and the denunciation of rivals — to trying to turn Labour, one of Britain’s two great parties that dominated the 20th century, from being a broad church into a party that stood only for his, by then, very dangerous brand of Left-wing extremism. In the wars of that period against Labour’s Right-wing and soft centre he did not operate alone, but he was the figurehead of a Bennite movement that created the conditions in which the SDP breakaway became necessary, splitting the Left and giving Margaret Thatcher an enormous advantage to the joy of Tories. When Labour crashed to defeat in 1983, Benn even said that the result was a good start because millions of voters had voted for an authentically socialist manifesto, which would have taken Britain back to the stone age if implemented.

From there, after a bitter interlude and a sulk, Benn began his final and, this time, wonderful transformation, during which he was elevated to the ranks of national treasure — a pipe-smoking man of letters, like a great National Trust property crossed with George Orwell. As with many journalists of my generation, I encountered him one on one only in that third phase, and found him, as many others did, a deeply courteous, amusing and interesting man. It was his defence of the Commons, against the Executive, that I liked, and when he spoke on such themes it was possible to imagine him at Cromwell’s elbow in the English Civil War, or printing off radical pamphlets before falling out with the parliamentary leadership after the King had had his head cut off.

December 19, 2013

April 10, 2013

In British political circles, the term “Thatcherism” conceals at least as much as it reveals

In sp!ked, Tim Black explains why the term “Thatcherism” is not actually a useful descriptor of Margaret Thatcher’s political ideology, but it helps hide the weaknesses of her political and ideological foes:

… for many of those who today preen themselves as left-wing, the idea of Thatcher is arguably even more important. And that’s because she can be blamed for everything that is wrong today. She may have left office nearly a quarter of a century ago, but so potent was the ideology she apparently promulgated — Thatcherism — that we as a nation continue to be in thrall to it. As one prominent left-wing columnist stated yesterday: ‘Thatcherism lives on. Nothing to celebrate.’ Ex-London mayor ‘Red’ Ken Livingstone agreed: ‘In actual fact, every real problem we face today is the legacy of the fact she was fundamentally wrong.’

Elsewhere, Johnathan Freedland at the liberalish-leftish Guardian joined the Thatcherism Lives chorus: ‘The country we live in remains Thatcher’s Britain. We still live in the land Margaret built.’ At the much-reported-upon, little-attended street parties in Brixton and Glasgow, staged in ironic honour of Thatcher’s passing, the belief that her ideas still walk among us was palpable. In the words of one 28-year-old student: ‘It is important to remember that Thatcherism isn’t dead and it is important that people get out on the street and not allow the government to whitewash what she did.’

[. . .]

And here is where reality stops and myth begins. Because that’s not what the left saw. They saw something more ideological than brutally pragmatic. They saw, in the words of Marxism Today editor Martin Jacques in 1985, ‘a novel and exceptional force’. They saw, in short, Thatcherism.

Given the fact that Thatcher herself never had an actual ideological project to which ‘Thatcherism’ might actually refer, it is unsurprising that a recent book on the subject admitted that ‘talk of “Thatcherism” obscures as much as it reveals’. Instead, the idea of Thatcherism always revealed far more about the left than it did about some perpetually elusive right-wing ideology. That is why the concept, first used by academic Stuart Hall in 1979, gained intellectual traction on the left in 1983, the year Labour, under the leadership of Michael Foot, suffered a devastating defeat at the General Election: it shifted the responsibility for failure from the Labour Party, and its complicity with so-called Thatcherite economics, to the working class, a social constituency supposedly seduced away from the Labour Party by Thatcher’s advocacy of social mobility and aspiration. The idea of ‘Thatcherism’ let Labour off the hook.

So the legacy of Thatcherism may indeed live on, as some sunk on the left insist. But not because of anything Thatcher herself did. It will live on because too many are more comfortable attacking a phantasm from the past than reckoning with political reality today.