Mansa Musa’s good intentions may be the first case in history of failed foreign aid. Known as the “Lord of the Wangara Mines”, Mansa Musa I ruled the Empire of Mali between 1312 and 1337. Trade in gold, salt, copper, and ivory made Mansa Musa the richest man in world history.

As a practicing Muslim, Mansa Musa decided to visit Mecca in 1324. It is estimated that his caravan was composed of 8,000 soldiers and courtiers — others estimate a total of 60,000 — 12,000 slaves with 48,000 pounds of gold and 100 camels with 300 pounds of gold each. For greater spectacle, another 500 servants preceded the caravan, and each carried a gold staff weighing between 6 and 10.5 pounds. When totaling the estimates, he carried from side to side of the African continent approximately 38 tons of the golden metal, the equivalent today of the gold reserves in Malaysia’s central bank — more than countries like Peru, Hungary or Qatar have in their vaults.

On his way, the Mansa of Mali stayed for three months in Cairo. Every day he gave gold bars to the poor, scholars, and local officials. Mansa’s emissaries toured the bazaars paying at a premium with gold. The Arab historian Al-Makrizi (1364-1442) relates that Mansa Musa’s gifts “astonished the eye by their beauty and splendor”. But the joy was short-lived. So much was the flow of golden metal that flooded the streets of Cairo that the value of the local gold dinar fell by 20 percent and it took the city about 12 years to recover from the inflationary pressure that such a devaluation caused.

Orestes R Betancourt Ponce de León, “5 Historic Examples of Foreign Aid Efforts Gone Wrong”, FEE Stories, 2021-06-06.

March 6, 2024

QotD: Mansa Musa’s disastrous foreign aid to Cairo

May 21, 2018

The Empire of Mali – Lies – Extra History – #6

Extra Credits

Published on 19 May 2018History, and the past, can be two different concepts. Is Mansa Musa REALLY that wealthy? Did his son really die of “sleeping sickness”? It’s time for Lies, featuring Robert Rath, Jac Kjellberg, and James Portnow!

May 14, 2018

The Empire of Mali – The Final Bloody Act – Extra History – #5

Extra Credits

Published on 12 May 2018The Mali Empire comes to an end after the rise of rival powers and weakened by colonial influences, but not without leaving a legacy as a place of wealth and splendor.

May 7, 2018

The Empire of Mali – The Cracks Begin to Show – Extra History – #4

Extra Credits

Published on 5 May 2018After Mansa Musa’s death, the rivers of gold started drying up, and bitterness snaked out from the fringes of the vast Mali Empire. Wars were coming…

EDIT: 7:45 says 1930s. Our scripts have this written down as the 1370s.

April 30, 2018

The Empire of Mali – Mansa Musa – Extra History – #3

Extra Credits

Published on 28 Apr 2018Mansa Musa is remembered as the richest person in the entire history of the world, but he also worked hard to establish the empire of Mali as a political and even religious superpower. However, his excessive wealth started creating bigger problems…

April 23, 2018

The Empire of Mali – An Empire of Trade and Faith – Extra History – #2

Extra Credits

Published on 21 Apr 2018Seeking a meeting with the emperor of the Mali Empire, a man named Ibn Battutah journeyed across the perilous Sahara sands to discover Mali’s gold… instead, he found out how Mali blended its Islamic and African cultures.

April 16, 2018

The Empire of Mali – The Twang of a Bow – Extra History – #1

Extra Credits

Published on 14 Apr 2018While the old Ghana Empire waxed wealthy due to taxes on trade passing through its lands, the new Empire of Mali born in its stead had expanded borders that included vast lands of gold…

March 15, 2017

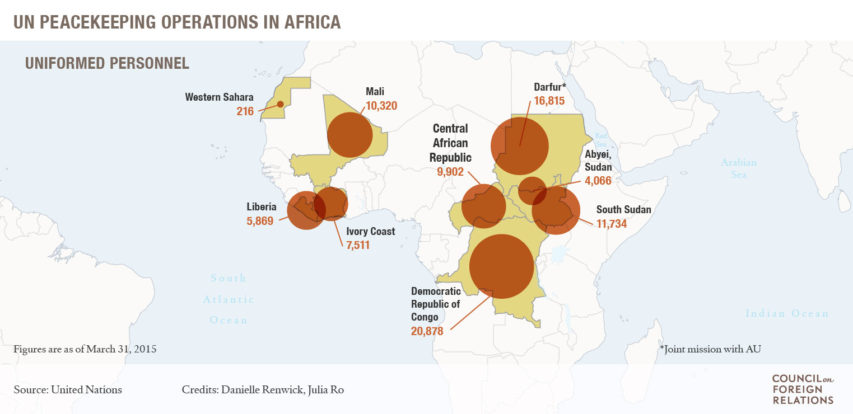

Sensible reasons to reject a Canadian peacekeeping mission in Africa

Ted Campbell explains why it would not be a good thing for Canada to send a peacekeeping force to Mali (or to anywhere else in Africa right now):

The Globe and Mail, in an editorial, asks the key question:

“Is there a Canadian national interest in sending troops to Mali?”I suggest that unless and until the Trudeau government can say, “yes,” and can explain that vital interest to most Canadians that sending Canadian soldiers off to Africa on a United Nations operation is problematical. “The Canadian Armed Forces shed blood and lost lives during the decade-long mission in Afghanistan,” the Globe‘s editorial says, “Sending them into a similar campaign in Mali may further Liberal political interests. But does it serve the national interest?“

Now, I believe that I can make a sensible, mid to long term case for Canada to be “engaged,” politically, economically and militarily in Africa:

- Africa will be, after Asia, the “next big deal” for economic growth, trade and, therefore, profits;

- Canada will want to be involved as a trusted friend when Africa is ready to “blossom” and have an economic “boom” of its own; and

- Despite Chinese and French incursions there are still plenty of opportunities for Canadian engagement.

In other words, we have interests in Africa; even, perhaps, in the mid to long term, we have vital interests, at that.

I cannot make a case for getting involved in any United Nations mission in Africa. I cannot, even with rose coloured glasses, see one single United Nations mission in Africa that is working, much less succeeding and doing some good.

I’m not opposed to the UN. In fact, I’m one of those who says that if it didn’t exist we’d have to invent it. The current UN is better than the old League of Nations, and some UN agencies, like the International Telecommunications Union, for example, do good work for the whole world and are, alone, worth our entire UN contribution, but we ask too much of the UN and it is neither well enough designed or led or organized or funded to do even a small percentage of what is asked of it. Peacekeeping is one of the things that the UN cannot do well in the 21st century. Peacekeeping was fine when it was ‘invented’ (circa 1948, by Ralph Bunche, and American and Brian Urquhart, a Brit, not by Lester Pearson in 1957, no matter what your ill-educated professors may have told you) but it could not be adapted to situations in which there is:

- No peace to be kept;

- A plethora of non-state actors who are not amenable to UN sanctions.

A few days ago I wrote about the risks involved in sending soldiers to Africa. The Globe and Mail‘s editorial just adds some more fuel to that fire.

February 3, 2013

US poised to increase involvement in Mali

Sheldon Richman explains why it could be a problem if the American presence in northwestern Africa is further expanded:

Ominously but unsurprisingly, the U.S. military’s Africa Command wants to increase its footprint in northwest Africa. What began as low-profile assistance to France’s campaign to wrest control of northern Mali (a former colony) from unwelcome jihadists could end up becoming something more.

The Washington Post reports that Africom “is preparing to establish a drone base in northwest Africa [probably Niger] so that it can increase surveillance missions on the local affiliate of Al Qaeda and other Islamist extremist groups that American and other Western officials say pose a growing menace to the region.” But before that word “surveillance” can bring a sigh of relief, the Post adds, “For now, officials say they envision flying only unarmed surveillance drones from the base, though they have not ruled out conducting missile strikes at some point if the threat worsens.”

Meanwhile Bloomberg, citing American military officials, says Niger and the U.S. government have “reached an agreement allowing American military personnel to be stationed in the West African country and enabling them to take on Islamist militants in neighboring Mali, according to U.S. officials.… No decision has been made to station the drones.”

The irony is that surveillance drones could become the reason the “threat worsens,” and could provide the pretext to use drones armed with Hellfire missiles — the same kind used over 400 times in Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia, killing hundreds of noncombatants. Moving from surveillance to lethal strikes would be a boost for jihadist recruiters.