The History Chap

Published Nov 16, 2023Britain’s Victorious Jungle War Against the Communists

Get My FREE Weekly Newsletter

https://www.thehistorychap.com

February 22, 2024

The Malayan Emergency – Britain’s Jungle War v Communists

October 12, 2023

Canada, “a country with short arms and long pockets”

In the National Post, John Ivison recounts Canada’s continuing inability to live up to expectations internationally, especially militarily:

On the eve of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Mark Norman, the former vice-chief of defence, made a prediction that sounded overblown at the time.

“I really think the Americans are going to start ignoring us because they don’t think we are credible or reliable. They are not even putting pressure on us anymore,” he said in a January 2022 National Post interview, based on his conversations with contacts in Washington.

It turns out he was absolutely right.

Since then, leaked Pentagon documents have confirmed that sense, indicating that the U.S. believes “widespread defence shortfalls have hindered Canada’s capabilities, while straining partner relationships and alliance contributions”.

Canada left little room for doubt about its diminished capabilities when it took a pass on NATO’s largest-ever air exercise last summer, because its jets and pilots were involved in “modernization activities”. That absence left the impression that this country might not be able to show up in certain circumstances.

Even before the unfolding tragedy in the Middle East, America was letting it be known that it felt overstretched and needed regional allies to share the burden.

When President Joe Biden visited Ottawa in March, he asked Justin Trudeau to lead a mission to Haiti, which had descended into mob rule. Since the Liberals were elected on a peacekeeping ticket in 2015, it was a logical request. However, Trudeau demurred, presumably on the grounds that Canada’s security forces were stretched too thin by operations in Latvia and fighting wildfires at home. The upshot is that Kenya is set to send 1,000 security officers to the beleaguered island nation.

The recent news that Canada now plans to trim its defence budget by nearly $1 billion — a total of $17 billion over 20 years, if savings are recurring — has reinforced the image of a country with short arms and long pockets.

Against that background, it was no surprise that on Monday Biden hosted a call with the leaders of France, Germany, Italy and the U.K. to discuss the crisis in the Middle East — and didn’t include Canada.

A statement by the G7 minus Canada and Japan (which has a negligible Jewish population) was issued saying that the five countries would ensure Israel is able to defend itself.

Over at The Line, Matt Gurney discovered that the federal government was actively trying to hide the fact that Canadians in Israel were not able to access Canadian embassy services by pretending that the word “operational” meant “open and functional”:

On Sunday evening (hours after we published our dispatch), I received a reply from GAC. This was the reply:

Since the beginning of this crisis, Canadian officials have been working around the clock to support Canadians. The missions in Tel Aviv and Ramallah remained operational through the weekend and will continue to be. Our missions will open on Monday October 9th, unless security conditions do not allow for it. We will be assessing the security situation daily, in coordination with our allies.

Okay! That seemed fair. But not having been born yesterday, and being in a profession where people try to spin me all the time, I noticed something immediately. The distinction GAC was drawing between “operational” and “open” stood out to me. I replied at once seeking clarification, and heard nothing back. Not even an acknowledgement.

This word choice mattered. The government publicly used the “operational” messaging. Members of the government repeated it. This was what they were telling the Canadian people: all is well, ignore those nasty media people and members of the opposition. Of course the embassies were “operational”!

See that tweet? The one pasted above? I checked out who was retweeting it. Lots of people did! And that included a bunch of Liberal MPs, a bunch of Canadian diplomats, members of the media, and what I’ll politely refer to as a group of “usual suspects” I recognize from online as being proxies for the Liberal government’s messaging (or at least really devoted True Believer Liberal partisans).

On Monday morning, having heard nothing back about what “operational” meant as opposed to “open”, I asked for a specific clarification in the terminology. What was “operational” vs. “open”? I also asked for specifics on what services were available locally from Canadian diplomatic missions in Israel over the weekend in real time, and how that would change when the embassy “opened” on Monday. I asked about the staffing level at the embassy on the weekend, and how that would compare to a normal workday, and also to a normal weekend.

Rather than answer a simple question, our government would much rather obfuscate and prevaricate as a matter of policy. That, by itself, tells you everything you need to know about both our political leaders and the civil service organizations they control.

September 26, 2022

May 31, 2022

A new history of the evil empire. No, not that one. Not that one either. The other evil empire!

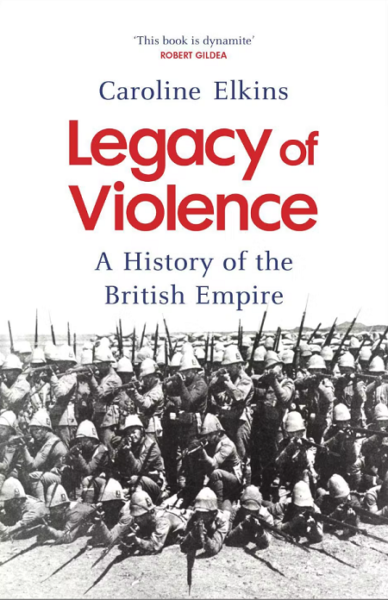

In The Critic, Barnaby Crowcroft reviews Caroline Elkins’ new history of the British empire, Legacy of Violence:

Elkins is correct that British decolonisation after the end of the war — if not “white-washed” — has got off lightly among historians, often via a contrast with the dreadful behaviour of the French. We remain far too influenced by the impression that Britain willingly and amicably handed over power (as Harold Macmillan put it) to Asian and African representatives of “agreeable, educated, Liberal, North Oxford society”.

There is a single map in this book which should definitively dispose of such ideas, showing all the colonial conflicts and states of emergency Britain was engaged in around the world after 1945. There are the well-known counterinsurgencies in Palestine, Malaya, Kenya, Cyprus and Aden. Alongside other, less well-known ones, however — British Guiana, Malaysia, Belize, Oman and the New Hebrides — bring us pretty much into the 1980s without a single year of global colonial peace.

In Kenya and Malaya, the British carried out massive coercive interventions in the 1950s, including the forcible resettlement of over a million people into closely monitored “new villages”, which, if they cannot be likened to concentration camps, certainly resemble the kinds of things the French were doing in Algeria. Difficult though it is to believe today, until very recently the British were a “warlike” and patriotic people, and their agents could be ruthless in the pursuit of imperial interest overseas.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to take seriously the more grandiose claims of Legacy of Violence, including Elkins’ presumption to have uncovered the Key to All Mythologies of British imperial wickedness in the form of Liberalism and Racism. The prose is part of the problem. Her introductory statement of the book’s bombastic aims reads more like something written by a professional satirist, than a professional historian.

“To study the British empire,” she writes, “is to unlock memory’s gate using the key of historical enquiry. But once inside, history’s fortress is bewildering … Unlike mythical fire-breathing monsters, however, the creatures inhabiting the annals of Britain’s imperial past are not illusions [but] monstrosities [which] inflicted untold suffering …”

Much of the book is given over to a plodding chronicle of nineteenth- and twentieth-century British history, in which events are construed — and often misconstrued — to give the meanest possible interpretation. British “arch-imperialists” resemble cartoon villains, who wear “Hitleresque moustaches” and “racist coattails” and are awarded MBEs and OBEs according to how much harm they inflict upon colonial subjects. There is even an imaginative reconstruction of British pilots all but laughing as they machine-gun “defenceless women and children”; readers are invited to listen to their “screams of pain”.

To determine whether Britain’s empire was uniquely violent invites the question: compared to what? Niall Ferguson earned opprobrium for suggesting in 2003 that alongside the rival empires which arose to challenge it in the middle of the twentieth century, Britain’s looked pretty attractive.

To her credit, Elkins does not disagree with this. Her treatment of Malaya’s communist insurgency suggests that she is not particularly exercised by violence when it is committed by ideological confrères. The only thing we get in the way of any broader comparison, however, is the notably wishy-washy one implied between the “East and the West”, which she describes as the contrast between “humanity and inhumanity”.

January 12, 2022

“You feel instantly at home when you arrive in Kenya because Kenya was once everyone’s home!”

When I was in middle school, my favourite teacher was a huge fan of the Leakey family’s discoveries in central Africa, and took every opportunity to show us films on the latest hominid remains uncovered (and by “latest”, it usually meant several years old, as 16mm films distributed through the county school system were rarely all that “new”). I assume she was a frustrated anthropologist herself, honestly, although I found her to be a very good teacher even if she’d “settled” for teaching as a career. In The Iconoclast, Geoffrey Clarfield remembers the late Richard Leakey, “the last Victorian scientist”, who died earlier this month in Kenya:

Richard Leakey at the WTTC Global Summit 2015.

Detail of original photo by the World Travel & Tourism Council via Wikimedia Commons.

Kenyan paleoanthropologist Richard Leakey died on January 2nd at age 77, following an extraordinary career devoted to the scientific exploration of human origins. Richard was once my boss. And although we never became friends, I came to know him fairly well.

He died peacefully in his house overlooking Kenya’s Great Rift Valley, where he’d made his most notable discoveries, and which occupied his imagination from an early age until his final days. It was fitting that he was buried beside his home, amid the same terrain from which he’d dug up humanity’s long-buried early ancestors. As I once heard him say to a group of visitors, “You feel instantly at home when you arrive in Kenya because Kenya was once everyone’s home!” (Essayists are supposed to shun exclamation marks, but this was simply the way the man spoke.)

To an outsider, Richard’s work history may appear to comprise a series of disconnected, sometimes testosterone-driven adventures. By turns, he was a wildlife trapper and animal trader, safari guide, bush pilot, gifted (albeit informally trained) fossil hunter, archaeological excavator, scientific autodidact, museum and civil-service administrator, member of parliament, opposition leader, cabinet minister, conservation activist, Kenyan patriot, fundraiser, public speaker, and prolific writer. The public knew him best as a television and film presenter. But those who knew him privately will also remember him as an enthusiastic team leader and mentor of young talent.

In my case, he helped advance my own project to train young Kenyan researchers to record and document traditional music in the northern part of their country, the Turkana District in particular. When I’d raised funds for this initiative, he brought it under the auspices of the National Museums of Kenya (NMK), of which he was then director.

While he may have seemed like something of an (enormously) overachieving dilettante to some, there was in fact a unity to his life and work. The times being what they are, many will focus on the fact that he was a white man taking a prominent role in a largely black country. But in truth, he likely attracted more scrutiny for being a fervent admirer of Charles Darwin, and a secular atheist, in a religious part of the world. He once published his own edited and illustrated version of Origin of Species, which I read when I was working for him, and his contributions to that volume gave me insight into what I believe was his fundamentally edifying professional motivation. I still have it on my shelf.

Richard emphasized that humankind had evolved in the Great Rift Valley, and from there had spread “out of Africa”, as the saying goes. He also believed that a previously underestimated factor in human evolution had been our species’ relationship to evolving biodiversity and prehistoric climate fluctuation — “paleoenvironments” as they came to be called.

March 3, 2021

QotD: Big game hunting

It was a confusion of ideas between him and one of the lions he was hunting in Kenya that had caused A. B. Spottsworth to make the obituary column. He thought the lion was dead, and the lion thought it wasn’t.

P.G. Wodehouse, Ring for Jeeves.

April 18, 2018

QotD: The United Nations

It’s a good basic axiom that if you take a quart of ice-cream and a quart of dog faeces and mix ’em together the result will taste more like the latter than the former. That’s the problem with the UN. If you make the free nations and the thug states members of the same club, the danger isn’t that they’ll meet each other half-way but that the free world winds up going three-quarters, seven-eighths of the way. Thus the Oil-for-Fraud scandal: in the end, Saddam Hussein had a much shrewder understanding of the way the UN works than Bush and Blair did.

And, of course, corrupt organisations rarely stop at just one kind. If you don’t want to bulk up your pension by skimming the Oil-for-Food programme, don’t worry, whatever your bag, the UN can find somewhere that suits — in West Africa, it’s Sex-for-Food, with aid workers demanding sexual services from locals as young as four; in Cambodia, it’s drug dealing; in Kenya, it’s the refugee extortion racket; in the Balkans, sex slaves.

Mark Steyn, “UN forces — just a bunch of thugs?”, Telegraph Online 2005-02-15

September 30, 2013

Modern terrorism isn’t anti-state … it’s anti-society

Tim Black discusses what we know and don’t know about the Kenyan terror attack and why recent terrorist attacks seem less directed at the organs of the state and much more at society as a whole:

Some analysts have even gone so far as to pinpoint Kenyan troops’ take over of the port of Kismayo, a lucrative trading position for al-Shabab, as the catalyst for the Westgate attack. As one commentator put it: ‘[The Westgate attack] wasn’t a random act. On the contrary, it was a direct consequence of Kenya’s own policy decisions. To say that in no way justifies this heinous attack – it merely identifies cause and effect.’

Yet tit-for-tat accounts miss something. They appear too glib, too easy. They may not excuse a drawn-out atrocity like Westgate, but they do give it a nicely polished rationale.

But it’s a rationale at odds with what actually happened. Yes, the Kenyan military, under the auspices of the African Union, did play a role in weakening al-Shabab’s position in Somalia. And no doubt members of al-Shabab, already a declining, increasingly unpopular grouping in Somalia (even Osama Bin Laden disowned it because of is brutality), did feel anger towards the Kenyan army. But there is a massive, unexplained causal gap between that sense of grievance and the attack on a shopping centre in Nairobi. That’s right, a shopping centre. This wasn’t an attack on the Kenyan state. This wasn’t a gun battle with the Kenyan army, the principal object of al-Shabab ire. No, this was an indiscriminate attack on men, women and children at a shopping centre. The people targeted weren’t intent on a conflict with militant Islamists in Somalia; they were shopping for Old El Paso fajita mix.

[…]

What’s important to grasp here is that the new terrorism does not draw its militants from any specific struggle in Somalia, or anywhere else for that matter. Rather, it draws upon a broad and deep disillusionment with modern society; it exploits the non-identity between society’s threadbare values and particular members. And it turns certain individuals upon society as a whole. Hence the new terrorism does not target the institutions of the state; it targets the institutions of civil society. In particular, it targets the embodiments of modern social life: a shopping centre in Nairobi, an office block in New York, a market in Baghdad.

In 1911, amid anarchist bomb plots, Vladamir Lenin wrote a scathing critique of what he called ‘individual terrorism’ — the act, for example, of assassinating a minister — on the grounds that it turned what could be a mass struggle into the act of a single individual. ‘In our eyes’, he wrote, ‘individual terror is inadmissible precisely because it belittles the role of the masses in their own consciousness, reconciles them to their powerlessness, and turns their eyes and hopes towards a great avenger and liberator who some day will come and accomplish his mission’. Today’s individual terrorist is far more degenerate than his anarchist precursors. So far removed from the masses is he, so little concerned is he with any actual struggle for something in particular, that his terror is turned against the masses. The consequences have been barbaric.

August 10, 2013

CBC notices social conservative group is critical of the government

This is probably the most attention the CBC has paid to REAL Women of Canada since … well, ever:

REAL Women of Canada, a privately funded socially conservative group, says Foreign Affairs Minister John Baird is imposing his own views on Uganda, Kenya and Russia when he criticizes those countries for passing legislation targeting homosexuals.

The group, which describes itself as a “pro-family conservative women’s movement,” issued a press release Wednesday decrying what it called Baird’s “abuse of office” and his awarding of a $200,000 grant to “special interest groups” in Uganda and Kenya “to further his own perspective on homosexuality.”

REAL Women also lambasted Baird for admitting he worked extensively behind the scenes to persuade Russia not to pass laws restricting foreign adoption of Russian children by gay couples and cracking down on gay rights activism to control the spread of “homosexual propaganda.”

Finally, the press release states, “Mr. Baird’s actions are destructive to the conservative base in Canada and causing collateral damage to his party.”

It’s not often that the CBC can find this kind of anti-Harper criticism coming from a group they would identify as being “core” Harper supporters, so it’s not surprising they give it the full treatment it really doesn’t deserve.

H/T to Brendan McKenna for the link.

May 19, 2012

January 13, 2012

Google Kenya’s motto: Do <strike>no</strike> evil

Someone at Google has some explaining to do:

Since October, Google’s GKBO appears to have been systematically accessing Mocality’s database and attempting to sell their competing product to our business owners. They have been telling untruths about their relationship with us, and about our business practices, in order to do so. As of January 11th, nearly 30% of our database has apparently been contacted.

Furthermore, they now seem to have outsourced this operation from Kenya to India.

When we started this investigation, I thought that we’d catch a rogue call-centre employee, point out to Google that they were violating our Terms and conditions (sections 9.12 and 9.17, amongst others), someone would get a slap on the wrist, and life would continue.

I did not expect to find a human-powered, systematic, months-long, fraudulent (falsely claiming to be collaborating with us, and worse) attempt to undermine our business, being perpetrated from call centres on 2 continents.

H/T to Megan McArdle for the link.

Update: BoingBoing got a response to their post on this issue from Google’s Vice-President for Product and Engineering, Europe and Emerging Markets:

We were mortified to learn that a team of people working on a Google project improperly used Mocality’s data and misrepresented our relationship with Mocality to encourage customers to create new websites. We’ve already unreservedly apologised to Mocality. We’re still investigating exactly how this happened, and as soon as we have all the facts, we’ll be taking the appropriate action with the people involved.

December 4, 2010

Looking for the remains of Zheng He’s treasure fleet

Virginia Postrel looks at the latest archaeological expedition in the Indian Ocean:

A team of Chinese archeologists arrived in Kenya last week, headed for waters surrounding the Lamu archipelago on the country’s northern coast. They hadn’t made the trip to study local history. They came to recover a lost Chinese past.

In the early 1400s, nearly a century before Vasco da Gama reached eastern Africa, Chinese records say that the great admiral Zheng He took his vast fleet of treasure ships as far as Kenya’s northern Swahili coast. Zheng visited the Sultan of Malindi, the most powerful local ruler, and brought back exotic gifts, including a giraffe. “Africa was China’s El Dorado — the land of rare and precious things, mysterious and unfathomable,” writes Louise Levathes in her 1994 history of Zheng’s voyages, “When China Ruled the Seas.”

Now the Chinese government is funding a three-year, $3 million project, in cooperation with the National Museums of Kenya, to find and analyze evidence of Zheng’s visits. The underwater search for shipwrecks follows a dig last summer in the village of Mambrui that unearthed a rare coin carried only by emissaries of the Chinese emperor, as well as a large fragment of a green-glazed porcelain bowl whose fine workmanship befits an imperial envoy. Although Ming-era porcelains are nothing new in Mambrui — Chinese porcelains fill the local museum and decorate a centuries-old tomb — the latest finds suggest that the wares came not through Arab merchants but directly from China.

China’s brief dabbling in overseas exploration ended fairly suddenly, but there was no technical reason that they could not have continued. It would be a very different world indeed if the Emperor hadn’t decided to ignore everything outside the Middle Kingdom.

The real problem with contemporary China’s version of the Zheng He story is that it omits the ending. In the century after Zheng’s death in 1433, emperors cut back on shipbuilding and exploration. When private merchants replaced the old tribute trade, the central authorities banned those ships as well. Building a ship with more than two masts became a crime punishable by death. Going to sea in a multimasted ship, even to trade, was also forbidden. Zheng’s logs were hidden or destroyed, lest they encourage future expeditions. To the Confucians who controlled the court, writes Ms. Levathes, “a desire for contact with the outside world meant that China itself needed something from abroad and was therefore not strong and self-sufficient.”