The Great War

Published 12 Sep 2020Sign up for Curiosity Stream and get Nebula bundled in: https://curiositystream.com/thegreatwar

The conflict between the Irish independence movement and the UK government had been heating up since 1919. The summer of 1920 brought a new level of escalation with the arrival of the the Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary. Former veterans of the First World War were brought in to quell the rebellion and get hold of the strongholds controlled by the IRA.

» SUPPORT THE CHANNEL

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/thegreatwar» OUR PODCAST

https://realtimehistory.net/podcast – interviews with World War 1 historians and background info for the show.» BUY OUR SOURCES IN OUR AMAZON STORES

https://realtimehistory.net/amazon *

*Buying via this link supports The Great War (Affiliate-Link)» SOURCES

Hart, Peter: The IRA and Its Enemies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998)Harvey, A.D: “Who Were the Auxiliaries?” The Historical Journal, Vol. 35, No. 3 (Sep. 1992)

Hopkinson, Michael: The Irish War of Independence (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002)

Leeson, David: The Black and Tans: British Police and Auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence, 1920-1921 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011)

McMahon, Sean: The War of Independence (Cork: Mercier Press, 2019)

O’Brien, Paul: Havoc: The Auxiliaries in Ireland’s War of Independence (Cork: Collins Press, 2017)

Riddell, George: Lord Riddell’s Intimate Diary of the Peace Conference and After: 1918-1923 (London: Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1933)

Roxbourgh, Ian: “The Military: The Mutual Determination of Strategy in Ireland, 1912-1921” in Duyvendak, Jan Willem & Jasper, James M. (eds) Breaking Down the State: Protesters Engaged (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2015)

Townshend, Charles: The Republic: The Fight for Irish Independence 1918-1923 (London: Penguin Books, 2014)

“Tubbercurry”, Manchester Guardian, 4 October 1920.

Hugh Martin: “‘Black and Tan’ Force a Failure”, Daily News, 4 October 1920.

» MORE THE GREAT WAR

Website: https://realtimehistory.net

Instagram: https://instagram.com/the_great_war

Twitter: https://twitter.com/WW1_Series

Reddit: https://reddit.com/r/TheGreatWarChannel»CREDITS

Presented by: Jesse Alexander

Written by: Jesse Alexander

Director: Toni Steller & Florian Wittig

Director of Photography: Toni Steller

Sound: Toni Steller

Editing: Toni Steller

Motion Design: Philipp Appelt

Mixing, Mastering & Sound Design: http://above-zero.com

Maps: Daniel Kogosov (https://www.patreon.com/Zalezsky)

Research by: Jesse Alexander

Fact checking: Florian WittigChannel Design: Alexander Clark

Original Logo: David van StepholdContains licensed material by getty images

All rights reserved – Real Time History GmbH 2020

September 13, 2020

Irish War of Independence – WW1 Veterans In A New Battle I THE GREAT WAR 1920

August 15, 2020

Miscellaneous Myths: The Book Of Invasions

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 14 Aug 2020The quintessential Irish mythological text, and … it’s about getting steamrolled by invaders. Now that’s what I call brand consistency!

Our content is intended for teenage audiences and up.

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/kguuvvq

MERCH LINKS: https://www.redbubble.com/people/OSPY…

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

July 22, 2020

Glorious Revolution | 3 Minute History

Jabzy

Published 21 Jul 2015Sorry about the delay I’ve been without internet while I’ve moved apartment. And thanks for the 9,000 subs

Thanks to Xios, Alan Haskayne, Lachlan Lindenmayer, William Crabb, Derpvic, Seth Reeves and all my other Patrons. If you want to help out – https://www.patreon.com/Jabzy?ty=h

Please let me know if I’ve forgot to mention you, I’m a little disorganized without internet.

July 10, 2020

English Civil War | 3 Minute History

Jabzy

Published 9 Mar 2015I cut quite a bit out to save time. I’ll try and do a video on the Protectorate or the Restoration soon.

March 17, 2020

QotD: The luck of the Irish

Making dark comments about the likelihood of an unhappy outcome is the way we Irish Catholics deal with anxiety, dread, and uncertainty. It’s our special pact with God: If we expect the worst, obsess about it, worry about it, drink about it, indulge in black humor, and honestly convince ourselves that something awful is going to happen, then God will step in and prevent said awful thing from happening just to mess with our heads. But you have to sincerely expect the worst, not just go through the motions. It’s when you expect good things to happen or keep happening — when you presume upon God — that bad things happen. Remember what happened when the Irish presumed upon all those potatoes?

Dan Savage, “Welcome Black”, AndrewSullivan.com, 2005-08-08.

March 15, 2020

Irish War of Independence – Black and Tans vs. IRA Guerrillas I THE GREAT WAR 1920

The Great War

Published 14 Mar 2020Sign up for Curiosity Stream and Nebula: https://curiositystream.com/thegreatwar

The movement for more Irish self determination had turned into a full out revolutionary movement by 1919. The British Empire was losing control over Ireland and by early 1920 was in a full out guerrilla war against the Irish Republican Army (IRA). To regain control more police forces were recruited with wide ranging authorities – and a lack of actual police training. With their mismatched equipment made from war supplies, they soon got the nickname “Black and Tans”.

» SUPPORT THE CHANNEL

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/thegreatwar

Merchandise: https://shop.spreadshirt.de/thegreatwar/» SOURCES

Bowen, Tom, “The Irish Underground and the War of Independence 1919-21” Journal of Contemporary History Vol. 8, No. 2 (Apr., 1973), pp. 3-23

Hopkinson, Michael, The Irish War of Independence, (Montreal & Kingston : McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002)

Leeson, David, The Black and Tans: British Police and Auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence, 1920-1921, (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2011)

Lowe, W.J., “Who Were the Black-and-Tans”, History Ireland (Autumn 2004)

Townshend, Charles, The Republic: The Fight for Irish Independence 1918-1923, (London : Penguin Books, 2013)

» SOCIAL MEDIA

Instagram: https://instagram.com/the_great_war

Twitter: https://twitter.com/WW1_Series

Reddit: https://reddit.com/r/TheGreatWarChannel»CREDITS

Presented by: Jesse Alexander

Written by: Mark Newton, Jesse Alexander

Director: Toni Steller & Florian Wittig

Director of Photography: Toni Steller

Sound: Toni Steller

Editing: Jose Gamez, Toni Steller

Mixing, Mastering & Sound Design: http://above-zero.com

Maps: Daniel Kogosov (https://www.patreon.com/Zalezsky)

Research by: Mark Newton

Fact checking: Florian WittigChannel Design: Alexander Clark

Original Logo: David van StepholdA Mediakraft Networks Original Channel

Contains licensed material by getty images

All rights reserved – Real Time History GmbH 2020

February 11, 2020

Hydrogen – the Fuel of the Future?

Real Engineering

Published 20 Apr 2018Thank you to Shell for sponsoring this video. Listen to the Intelligence Squared Podcast for more: https://www.intelligencesquared.com/i…

Instagram:

https://www.instagram.com/brianjamesm…Additional Reading: https://go.shell.com/2qLmhWv

Get your Real Engineering merch at: https://standard.tv/collections/real-…

Patreon:

https://www.patreon.com/user?u=282505…

Instagram:

https://www.instagram.com/brianjamesm…

Twitter:

https://twitter.com/FiosrachtMy Patreon Expense Report:

https://goo.gl/ZB7kvKThank you to my patreon supporters: Adam Flohr, darth patron, Zoltan Gramantik, Henning Basma, Karl Andersson, Mark Govea, Mershal Alshammari, Hank Green, Tony Kuchta, Jason A. Diegmueller, Chris Plays Games, William Leu, Frejden Jarrett, Vincent Mooney, Ian Dundore, John & Becki Johnston. Nevin Spoljaric, Kedar Deshpande

Music:

“Sydney Sleeps Alone Tonight” by eleven.five & Dan Sieg [Silk Music]

“Hydra” by Huma-Huma, and “Dawn” by Andrew Odd [Silk Music]

Silk Music: http://bit.ly/MoreSilkMusic

December 25, 2019

Repost – “Fairytale of New York”

Time:

“Fairytale of New York,” The Pogues featuring Kirsty MacColl

This song came into being after Elvis Costello bet The Pogues’ lead singer Shane MacGowan that he couldn’t write a decent Christmas duet. The outcome: a call-and-response between a bickering couple that’s just as sweet as it is salty.

November 23, 2019

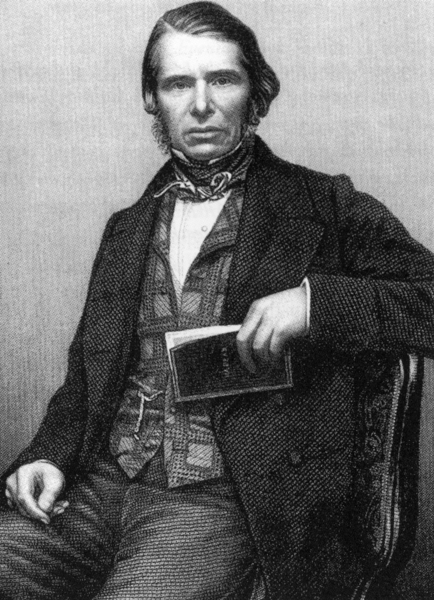

Sir Charles Trevelyan, head of the Irish relief efforts during the potato famine, and creator of the modern civil service

By happenstance, after posting the OSP video on the history of Ireland, a post at Samizdata covered one of the questions I had from OSP’s summary, specifically that the famine was worsened by British “laissez-faire mercantilism”. Mercantilism is rather different from any kind of laissez-faire system, so it was puzzling to hear Blue link them together as though they were the same thing. Of course, I live in a province currently governed by the Progressive Conservative party, so it’s not like I’m unable to process oxymorons as they go by…

Anyway, this post by Paul Marks looks at the man in charge of the relief efforts:

Part of the story of Sir Charles Trevelyan is fairly well known and accurately told. Charles Trevelyan was head of the relief efforts in Ireland under Russell’s government in the late 1840s – on his watch about a million Irish people died and millions more fled the country. But rather than being punished, or even dismissed in disgrace, Trevelyan was granted honours, made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB) and later made a Baronet, not bad for the son of the Cornishman clergyman. He went on to the create the modern British Civil Service – which dominates modern life in in the United Kingdom.

Charles Edward Trevelyan (contemporary lithograph). This appeared in one of the volumes of “The drawing-room portrait gallery of eminent personages principally from photographs by Mayall, many in Her Majesty’s private collection, and from the studios of the most celebrated photographers in the Kingdom / engraved on steel, under the direction of D.J. Pound; with memoirs by the most able authors”. Many libraries own copies.

Public domain, via Wikimedia.With Sir Edwin Chadwick (the early 19th century follower of Jeremy Bentham who wrote many reports on local and national problems in Britain – with the recommended solution always being more local or central government officials, spending and regulations), Sir Charles Trevelyan could well be described as one of the key creators of modern government. If, for example, one wonders why General Douglas Haig was not dismissed in disgrace after July 1st 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme when twenty thousand British soldiers were killed and thirty thousand wounded for no real gain (the only officers being sent home in disgrace being those officers who had saved some of them men by ordering them stop attacking – against the orders of General Haig), then the case of Sir Charles Trevelyan is key – the results of his decisions were awful, but his paperwork was always perfect (as was the paperwork of Haig and his staff). The United Kingdom had ceased to be a society that always judged someone on their success or failure in their task – it had become, at least partly, a bureaucratic society where people were judged on their words and their paperwork. A General, in order to be great, did not need to win battles or capture important cities – what they needed to do was write official reports in the correct administrative manner, and a famine relief administrator did not have to actually save the population he was in charge of saving – what he had to do was follow (and, in the case of Sir Charles, actually invent) the correct administrative procedures.

But here is where the story gets strange – every source I have ever seen in my life, has described Sir Charles Trevelyan as a supporter of “Laissez Faire” (French for, basically, “leave alone”) “non-interventionist” “minimal government” and his policies are described in like manner. […]

Which probably explains why Blue used the term in the previous video. Then these “laissez-faire” policies are summarized, which leads to this:

None of the above is anything to do with “laissez faire” it is, basically, the opposite. Reality is being inverted by the claim that a laissez faire policy was followed in Ireland. A possible counter argument to all this would go as follows – “Sir Charles Trevelyan was a supporter of laissez faire – he did not follow laissez faire in the case of Ireland, but because he was so famous for rolling back the state elsewhere (whilst spawning the modern Civil Service) – it was assumed that he must have done so in the case of Ireland“, but does even that argument stand up? I do not believe it does. Certainly Sir Charles Trevelyan could talk in a pro free market way (just as General Haig could talk about military tactics – and sound every inch the “educated soldier”), but what did he actually do when he was NOT in Ireland?

I cannot think of any aspect of government in the bigger island of the then UK (Britain) that Sir Charles Trevelyan rolled back. And in India (no surprise – the man was part of “the Raj”) he is most associated with government road building (although at least the roads went to actual places in India – they were not “from nowhere to nowhere”) and other government “infrastructure”, and also with the spread of government schools in India. Trevelyan was passionately devoted to the spread of government schools in India – this may be a noble aim, but it is not exactly a roll-back-the-state aim. Still less a “radical”, “fanatical” devotion to “laissez faire“.

History Summarized: Ireland

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 22 Nov 2019Get 3 months of Audible for just $6.95 a month — that’s more than half off the regular price. Choose 1 audiobook and 2 Audible Originals absolutely free. Visit http://www.audible.com/overlysarcastic or text “

overlysarcastic” to 500 500.While the rest of Europe was flailing aimlessly through the Dark Ages, Ireland was both preserving the ancient world and setting the stage for the Medieval Period. Then England showed up.

Sources & Further Reading:

How the Irish Saved Civilization: https://www.audible.com/pd/How-the-Ir…

Modern Ireland: 1600 — 1972 by R.F. FosterMusic from https://filmmusic.io

“Marked”, “Traveler”, “God Rest Ye Merry Celtishmen” by Kevin MacLeod (https://incompetech.com)

License: CC BY (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b…)Our content is intended for teenage audiences and up.

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/sS5K4R3

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

MERCH LINKS: https://www.redbubble.com/people/OSPY…

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

September 30, 2019

Ten Minute History – The Early British Empire

History Matters

Published on 26 Sep 2016Twitter: https://twitter.com/Tenminhistory

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/user?u=4973164This episode of Ten Minute History (like a documentary, only shorter) covers the birth and rise of the British Empire from the reign of Henry VII all the way to the American Revolution. The first part deals with the Tudors and their response to empire in Spain (as well as the Spanish Armada). The second part deals with England’s (and later Britain’s) establishment of its own empire in North America and India. It then concludes with the Seven Years’ War and the American Revolution.

Ten Minute History is a series of short, ten minute animated narrative documentaries that are designed as revision refreshers or simple introductions to a topic. Please note that these are not meant to be comprehensive and there’s a lot of stuff I couldn’t fit into the episodes that I would have liked to. Thank you for watching, though, it’s always appreciated.

August 9, 2019

QotD: Early milestones in aviation

… on June 15th 1919 Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Brown landed their Vickers Vimy airplane in a bog near Connemara, County Galway and thereby completed the first successful transatlantic flight: They had set off from St John’s, Newfoundland about fourteen hours earlier. What with having to get to the airport three hours early to shuffle through Homeland Security, we haven’t as a practical matter improved much on flight time over the last hundred years. It was also the first transatlantic air mail delivery, as, shortly before takeoff, the Royal Mail decided to give Alcock and Brown a couple of sacks of post for Britain.

A couple of weeks later, on July 6th 1919 the first east-west transatlantic flight landed at Mineola on Long Island. The RAF airship R34 had left East Fortune in Scotland four days earlier, having been hastily converted to hold passengers, and with a plate welded to an engine exhaust pipe to enable it to cook and serve hot food, which is more trouble than most airlines would go to today. A tabby kitten called Wopsie who served as the crew’s mascot stowed away on the flight, and because nobody at the Long Island end knew anything about landing large airships Major E M Pritchard parachuted out a little early, and became the first man to land on North American soil by air from Europe.

These briefly famous men did not get to savor their celebrity for long: Major Pritchard died in 1921 when the R38 airship exploded over the Humber estuary; his body was never found. Captain Alcock, just six months after his triumph and being knighted by George V, died at Rouen in Normandy in December 1919 when his new Vickers Viking crashed en route to the Paris air show.

Mark Steyn, “Come, Josephine, in My Flying Machine”, SteynOnline, 2019-07-07.

July 22, 2019

No Flag Northern Ireland

July 11, 2019

QotD: English is weird

English started out as, essentially, a kind of German. Old English is so unlike the modern version that it feels like a stretch to think of them as the same language at all. Hwæt, we gardena in geardagum þeodcyninga þrym gefrunon – does that really mean “So, we Spear-Danes have heard of the tribe-kings’ glory in days of yore”? Icelanders can still read similar stories written in the Old Norse ancestor of their language 1,000 years ago, and yet, to the untrained eye, Beowulf might as well be in Turkish.

The first thing that got us from there to here was the fact that, when the Angles, Saxons and Jutes (and also Frisians) brought their language to England, the island was already inhabited by people who spoke very different tongues. Their languages were Celtic ones, today represented by Welsh, Irish and Breton across the Channel in France. The Celts were subjugated but survived, and since there were only about 250,000 Germanic invaders – roughly the population of a modest burg such as Jersey City – very quickly most of the people speaking Old English were Celts.

Crucially, their languages were quite unlike English. For one thing, the verb came first (came first the verb). But also, they had an odd construction with the verb do: they used it to form a question, to make a sentence negative, and even just as a kind of seasoning before any verb. Do you walk? I do not walk. I do walk. That looks familiar now because the Celts started doing it in their rendition of English. But before that, such sentences would have seemed bizarre to an English speaker – as they would today in just about any language other than our own and the surviving Celtic ones. Notice how even to dwell upon this queer usage of do is to realise something odd in oneself, like being made aware that there is always a tongue in your mouth.

John McWhorter, “English is not normal”, Aion, 2015-11-13.

May 20, 2019

A Guide to Dark Age British Politics

History With Hilbert

Published on 26 Sep 2017A beginner’s guide to the politics of Dark Age Britain, from the southern Celts to the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and the Pictish north.