World War Two

Published 27 Feb 2024Hitler hopes that the V-2 rocket will turn the tide of the war. It’s cutting edge technology and impossible to intercept. Right now, the first long-range ballistic missile is raining death on London and Antwerp. But is it too little, too late? Find out the backstory to this powerful weapon.

(more…)

February 28, 2024

V-2: Hitler’s Wunderwaffe

February 27, 2024

The Company that Broke Canada

BobbyBroccoli

Published Nov 4, 2023For a brief moment, Nortel Networks was on top of the world. Let’s enjoy that moment while we can. Part 1 of 2.

00:00 This is John Roth

02:04 The Elephant and the Mouse

12:47 Pa without Ma

26:27 Made in Amerada

42:15 Right Turns are Hard

57:43 Silicon Valley North

1:07:37 The Toronto Stock Explosion

(more…)

February 25, 2024

QotD: From the M1903 Springfield to the M1 Garand

The M1 Garand is correctly considered the best battle rifle of World War II. It was the only semi-automatic rifle — meaning that it fired each time the operator pulled the trigger — to be the standard issue infantry rifle of any army during the war. Other forces were equipped with bolt-action rifles — the British Lee Enfield, Soviet Mosin Nagant, Japanese Type 99, German K98k, etc. — that required the operator to manually pull back a bolt to eject the [expended cartridge], and then push it forward again to insert a fresh cartridge into the chamber. The most obvious advantage was an increased rate of fire: a semiautomatic rifleman with an M1 had an official aimed rate of fire of 24 shots per minute.1 Compare this to the 15 aimed shots that British soldiers were expected to pop off with a bolt-action Lee Enfield in a “mad minute” drill. And the Lee Enfield was one of the fastest bolt-action rifles ever produced! In a pinch, a GI could blast out a clip in a few seconds, approximating a burst from an automatic weapon.2 Furthermore, with semi-automatic fire, the shooter could stay focused on his target, whereas working the bolt generally forced the shooter off target, requiring time to reacquire a proper sight picture.

Lt. General George Patton famously called the M1 Garand “the greatest battle implement ever devised“, a quote often repeated reverently in the context of World War II nostalgia. The US Government after the war gave away millions of M1 Garands, making it a popular civilian rifle for hunting and competitive shooting.

But nostalgia aside, it is also possible to view, from the high perch of hindsight, the M1 Garand as a missed opportunity. The most advanced battle rifle of World War II ultimately looked back too much to the past rather than pointing the way to the future. During its development, senior military officials applied the perceived lessons of the Spanish American War to a rifle designed to solve the problems of the Great War. This intervention prevented the M1 Garand from becoming something closer to a modern assault rifle, with an intermediate power cartridge and higher magazine capacity. The army was in no hurry to ditch the rifle that had won World War II, meaning that the United States did not field its first true assault rifle until two decades after the concept had been invented by the Germans in 1943 and soon successfully adapted by the Soviets in 1947. The first American assault rifle, the M16, would not debut until 1965.

First a necessary caveat: rifles were not the decisive weapon in World War II. For the most part the small arms deployed by the United States had been designed to fight World War I: the Browning Automatic Rifle (1918), the M1919 Browning Medium Machine Gun (as the date implies, first fielded in 1919) and the M2 Browning heavy machine gun, designed in 1918 and so good it is still used over a century later. In contrast, German machine guns were somewhat more recent in design: the MG 34 (as the name implies, first fielded 1934) and the MG 42. During the war, the Germans invented the first true assault rifle, the StG 44.

The secret sauce of the US Army by 1944-45 had little to do with firearms at all: it was a combination of ready mobility through motorization combined with deadly artillery and close air support, enabled by an unmatched communication system that allowed forward observers to direct and adjust fires to lethal effect. The American way of war was rooted in fleets of trucks and jeeps, networks of radios and heaps of shells. Having a nice semi-automatic rifle was ancillary to a conflict like World War II. But the M1 Garand is a useful window into the vagaries of military procurement and technological innovation, which require developers to at once predict the operational environment of the future and analyze the lessons of the past.

Throughout the 1920s, officers at the Infantry School in Fort Benning experimented with new tactics that they hoped would again allow for mobile infantry combat and avoid the trench stalemate of World War I. The basic solution was some form of “fire and maneuver”, in which one section of a unit (say a squad or platoon) would lay down a sufficient base of small arms fire to suppress the enemy so as to facilitate the other section’s advance. By alternating suppression and assault the element might leapfrog its way forward, even against entrenched enemy machine guns.

For such a tactic to work, infantry platoons needed a lot of firepower. Some might come from light machine guns, like the Browning Automatic Rifle, which was issued to individual infantry squads. But it was generally realized that individual infantrymen needed to be capable of a far higher rate of fire than could be provided by the standard issue rifle, the bolt-action M1903 Springfield, fed from a five round magazine. To this end, the US government set about developing a semi-automatic rifle.

The charge was taken up by John C. Garand, a Canadian-born, self taught firearms designer who worked for the Springfield Armory in Massachusetts. Garand’s solution to make the rifle self-loading was to insert a piston beneath the barrel. When the gunpowder exploded in the cartridge, the gas produced in the explosion propelled the bullet out the barrel. But some gas was bled off into a cylinder below the barrel (which gives the M1 its peculiar appearance of seeming to have two barrels); the pressure of the gas in the cylinder drove a piston.3 This piston attached to an operating rod which pushed the bolt of the rifle back, ejecting the spent casing, and allowing a spring in the internal magazine to insert another cartridge into the chamber before a separate spring pushed the operating rod forward and closed the bolt for the next shot, all in a fraction of a second.

Garand had initially worked on a rifle chambering the standard .30-06 cartridge used by the M1903 Springfield rifle (the .30 indicates that the bullet had a diameter of .30 inches, while the 06 indicates that the cartridge had been adopted in 1906; the round is often pronounced “thirty-ought-six”. But when a rival designer named John Pedersen, also affiliated with Springfield Armory, developed a semi-automatic design that chambered a lighter .276 (7mm) round, Garand retooled his project for the lighter round as well, producing a prototype known as the T3, with subsequent refinements labeled the T3E1 and T3E2. The smaller round meant that the internal magazine of the T3E1/2 could accept clips of 10 bullets, doubling the magazine capacity of the M1903 Springfield.

Army officials were very interested in the new round, but wanted proof that a lighter bullet would be sufficiently lethal in combat. A series of grisly ballistic tests were therefore ordered, pitting the .276 round against the traditional .30-06. In 1928, anesthetized pigs were shot through with both rounds. To the surprise and consternation of traditionalists, the .276 did far more damage in the so-called “Pig Board”. This is not paradoxical: the lighter round was more likely to “tumble”, precisely because it was lighter and so more likely to have its trajectory disrupted by bone and tissue; the tumble meant that more of the kinetic energy was expended inside the target, causing far more damage. The .30-06, meanwhile, as a more powerful round, was more likely to punch clean through, retaining its kinetic energy to keep moving forward after passing through the target. Eventually, tests of this sort would be used to sell the army on the lethality of the 5.56mm round used by the M16/M4, which has an even greater tumble, and causes even more grievous injuries. Out of concern that the fat bodies of pigs did not accurately replicate the human teenagers that the new round was designed to kill, a new test was inflicted upon goats, seen as more appropriately lean and therefore better analogs. The result was the same in favor of the .276 (a lighter .256 performed even better). With two rounds of tests vindicating the .276, the Army demanded that its new rifle chamber the .30-06. The final decision was made by Douglas MacArthur himself.

The .30-06 round itself had been the product of a painful lesson learned during the Spanish American War. Here, American troops, armed with Krag M1892 rifles, had found themselves badly out-ranged by Spanish troops armed with Mausers; the famous charge up San Juan Hill occurred after US troops had advanced for some distance under a hail of unanswered rifle fire. Given the importance of sharp shooting to the American military mythos, getting handily outranged and outshot by Spanish forces was a painful embarrassment. The first order of business had been to adopt the Mauser design: the M1903 Springfield was essentially a modified Mauser, as the US government had licensed a number of Mauser’s patents. By upgrading the M1903 to take the heavy .30-06 round, the Army ensured that soldiers could engage targets over a kilometer away. Beyond the deeply ingrained “lessons learned” from the Spanish American War, the mythos of the deadly American sharpshooter was strongly entrenched. Even as disruptors at Benning developed new infantry tactics that stressed volume of fire over accuracy, the phantoms of buck skinned frontiersmen sniping at British redcoats from a thousand paces still occupied the headspace of military leaders; they wanted a rifle with long distance accuracy. The sights on the M1 Garand adjust out to 1200 yards.

But MacArthur’s reasoning seems to have been primarily motivated by administrative and logistical concerns, as he cited the generic difficulties of fielding a lighter round. Some of these challenges may have been related to production and distribution of a sufficient stockpile of new caliber ammunition. There may have also been a concern with the new round complicating the logistics of line companies. The army also used .30-06 for the BAR and Browning medium machine gun, and having all of these shoot the same round in theory simplified the supply of line companies, and allowed for cross-leveling between weapons systems. Similar concerns have the US Army maintaining a policy of only having 5.56mm weapons at the squad level (thus the M4 and M249 Squad Automatic Weapon both shoot 5.56, and the SAW can shoot from M4 magazines).4 Still, MacArthur’s concerns seem unfounded in hindsight. The United States was about to produce billions of bullets during World War II. American troops were about to be so lavishly supplied that distributing two types of bullets would have been readily feasible given the soon to be proven quality of American logistics.5

With MacArthur’s edict, Garand retooled his rifle back to the .30-06 caliber, and his design was finally accepted in 1936. But the larger and more powerful round required a design change: the internal magazine now took clips of eight bullets instead of ten. Two rounds may not sound like much, but every bullet can be precious in a firefight, and this represented a 20% reduction in magazine capacity. Spread over a company sized element, the reduced clip capacity represented over two-thousand fewer rounds that a company commander could expect to fire and maneuver with. Indeed, the M1’s volume of fire proved generally insufficient to suppress the enemy on its own during the war, evidenced by the habit of equipping rifle squads with two Browning Automatic Rifles, instead of one. Marine divisions by the end of the war often deployed three BARs per squad.6

Michael Taylor, “Michael Taylor on The Development of the M1 Garand and its Implications”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-09-08.

1. TM 9-1005-222-12.

2. Thus George Wilson, a platoon leader and later company commander in the Fourth Infantry Division, describing a platoon scout stumbling upon the enemy: “The second scout emptied the eight round clip in his M-1 so fast it seemed like a machine gun … the rest of us moved very cautiously and found three dead enemy soldiers in the road.” (G. Wilson. If You Survive. Ivy, 1987).

3. John Garand’s initial design, and early production M1s, had a gas trap inserted over the muzzle to catch the gas after the bullet had exited; when this proved prone to fouling, a design modification drilled a small hole in the barrel just before the muzzle to allow the gas to bleed into the cylinder, most M1 Garands had this “gas port” system.

4. In 2023, US Army infantry will begin transition to the M7 carbine and M250 Squad Automatic weapon, which will both use a 6.8mm bullet, out of concerns that the 5.56 NATO is insufficient to penetrate body armor.

5. Editor’s Note: I agree with Michael here in principle: US logistics could have managed this. But I would also note that part of the reason American logistics were so good is that they applied MacArthur’s reasoning to everything, reusing vehicle chassis, limiting the number of different ammunition calibers and demanding interchangeable parts across the whole range of military equipment. Take one of those decisions away and the whole still functions. Take all of them away and one ends up with the mess that was German production and logistics.

6. Editor’s Note: BAR goes BARRRRRRRRRRR.

February 23, 2024

The Gun Science Says Can’t Work – Madsen LMG Mechanics

Forgotten Weapons

Published 21 Nov 2023The Madsen LMG is generally considered an extremely complex and confusing system — but is it really? Today we are taking one apart to see just how it actually works. Because in fact, it’s a very unusual system, but not really any more complicated than any other easy self-loading action.

(more…)

February 20, 2024

Belt-fed Madsen LMG: When the Weird Get Weirder

Forgotten Weapons

Published Nov 15, 2023First produced in 1902, the Madsen was one of the first practical light machine guns, and it remained in production for nearly 5 decades. The Madsen system is a rather unusual recoil-operated mechanism with a tilting bolt and a remarkably short receiver. The most unusual variation on the system was the belt-fed, high rate-of-fire pattern developed for aircraft use. This program was initiated by the Danish Air Force in the mid 1920s, and several different patterns were built by the time World War Two erupted.

The model here was actually a pattern that was under production for Hungary when German forces occupied Denmark. Taking over the factory, they continued the production and the guns went to the Luftwaffe for airfield defensive use.

In order to use disintegrating links instead of box magazines, some very odd modifications had to be made to the Madsen. One set of feed packs are actually built into the belt box itself, and the gun cannot function without the box attached. The only feasible path for empty link ejection is directly upwards, and so a horseshoe-shaped link chute was attached to the top cover, guiding links up over the gun and dropping them out the right side of the receiver. Very weird!

While several thousand of these were made under German occupation, very few survive today and they are extremely rare on the US registry.

(more…)

February 16, 2024

What remains of the “first” steam powered passenger railway line?

Bee Here Now

Published 23 Oct 2023The Stockton-Darlington Railway wasn’t the first time steam locomotives had been used to pull people, but it was the first time they had been used to pull passengers over any distance worth talking about. In 1825 that day came when a line running all the way from the coal pits in the hills around County Durham to the River Tees at Stockton was opened officially. This was an experiment, a practice, a great endeavour by local businessmen and engineers, such as the famous George Stephenson, who astounded crowds of onlookers with the introduction of Locomotion 1 halfway along the line, which began pulling people towards Darlington and then the docks at Stockton.

This was a day that would not only transform human transportation forever, but accelerate the industrial revolution to a blistering pace.

In this video I want to look at what remains of that line — not the bit still in use between the two towns, but the bit out in the coalfields. And I want to see how those early trailblazers tackled the rolling hills, with horses and stationary steam engines to create a true amalgamation of old-world and new-world technologies.

(more…)

February 2, 2024

The Sad Story of Churchill’s Iceman, Geoffrey Pyke

World War Two

Published Jan 31, 2024Geoffrey Pyke is remembered as an eccentric scientist who spewed out ideas like giant aircraft carriers made of icy Pykerete. But there was much more to him than that. He was a spy, a special operations mastermind, and his novel ideas contributed to the success of D-Day.

(more…)

J.M. Browning Harmonica Rifle

Forgotten Weapons

Published Sep 6, 2015Have you heard of Jonathan Browning, gunsmith and inventor? Among his other accomplishments, he is credited with designing the harmonica rifle in the US — and we have an example of one of his hand-made guns here to look at today (made in 1853). Browning was a Mormon, and spent several years slowly moving west periodically setting up gunsmithing shops before he reached his final destination of Ogden, Utah. There he settled down for good, and had 22 children with his 3 wives. One of those children also showed an aptitude for gunsmithing, and formally apprenticed to his father. You might recognize his name …

January 31, 2024

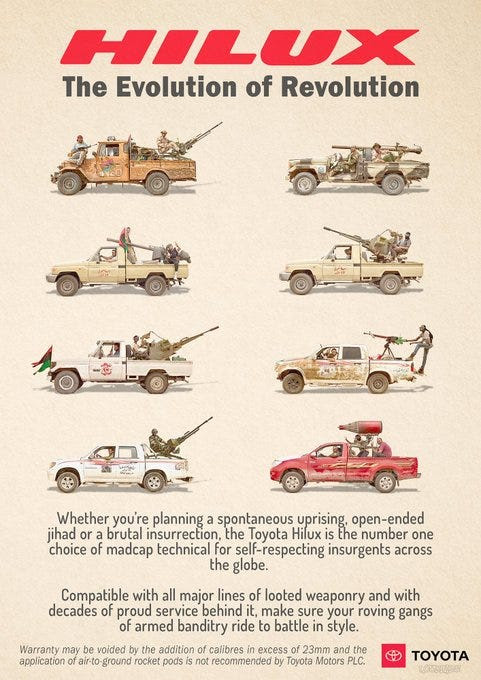

The rise of the “Technical”

Kulak at Anarchonomicon considers the innovation and adaptability that Chad’s ragtag forces displayed in the late 1980s to drive Libyan forces out of their territory, specifically the military use of Toyota pickup trucks as improvised gun carriages:

The Great Toyota War of 1987 was the final phase of the Chadian-Libyan conflict. Gadhafi’s Libyan forces by all rights should have dominated the vast stretches of desert being fought over: the Chadian military was less than a 3rd the size of the Libyan, and the Libyans were vastly better equipped fielding hundreds of tanks and armored personnel carriers, in addition to dozens of aircraft … to counter this the Chadians did something unique … They mounted the odds and ends heavy weapons systems they had in the truck beds of their Toyota pickups, and using the speed and maneuverability of the Toyotas, managed to outperform Libya’s surplus tanks and armored vehicles. By the end of the Chadian assault to retake their northern territory, the Libyans had suffered 7500 casualties to the Chadians 1000, with the Libyan defeat compounded by the loss of 800 armored vehicles, and close to 30 aircraft captured or destroyed.

The maneuverability and speed of the pickups made them incredibly hard to hit, and the tanks in particular struggled to get a sight picture … strafing within a certain range the pickups moved faster across the horizon than the old soviet tanks’ main gun could be hand cranked around to shoot them.

Since then Technology has become the backbone of insurgencies, militias, poorer militaries, and criminal cartels around the world. The ready availability of civilian pickups, with the ability of amateur mechanics to mount almost any weapon system in their truck-bed means that this incredibly simple system is about the most cost-effective and easy way for a small force to make the jump to mounted combat and heavy weapon.

But these weapons are far less asymmetric than motorcycles. The increasing importance of mobility means even the most advanced armies are getting in on the game. The US Army is currently converting a portion of its Humvees to have their rear seat and trunk cut out for a truck bed so that they can run a mobile light artillery out of it:

Popular Mechanics article – https://www.popularmechanics.com/military/weapons/a28288/hawkeye-humvee-mounted-howitzer/

The importance of instant maneuverability far outstretches any advantage armor can give in this application. Since artillery shells are radar-detectable, and, follow a parabolic arc, their origin point is easily calculable. Thus shoot and Scoot tactics are necessary since it may only be a minute or two from firing a volley that counter artillery fire might be inbound.

Aside from The bemused jokes that the US is finally catching up with the tech Chad had in the 80s, The truth is most advanced forces have always had something light with a heavy gun that can travel at highway speeds … the fact the US is now converting Humvees to have full light artillery pieces is only really a continuation of the trend of semi-auto grenade launchers, TOW missiles, or anti-tank guns being placed on light fast vehicles since WW2.

The remarkable thing about the technical isn’t that they’re some unique capability militaries can’t use … most poorer countries field something equivalent (the Libyans seemed to have screwed up the unit composition of their force) … Rather the unique advantage is how easy and cheap they are for non-conventional or poorer forces to home assemble.

US combat-ready Humvees cost the military into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, a cost that is presumably even higher as they’re modified to carry heavy weapons systems.

As ridiculous as a Toyota with an Air-to-Ground rocket pod, or a repurposed anti-air gun might be, they’re cheap. The pickup truck new is $20,000-50,000, though I suspect any irregular force would pay closer to 1000-5,000 for something decades old, if they pay at all. Likewise, they’re trivial to source, which is good if sanctions or anti-money laundering laws are trying to stop you from buying anything, and as the Chadians proved: pretty much any captured or surplus heavy weapon will go on it.

This gets irregular forces into the mounted combat game … but it does slightly more than that. Pickup trucks, as any perturbed Prius driver will tell you, are shockingly common … perhaps one in 10 or more vehicles out there are some form of pickup truck. This not only makes them easy to source, but it disguises them and allows them to operate hidden amongst the rolling stock of civilian vehicles, requiring either visual identification or extensive intelligence work to tell them from mere civilians.

This combination of mobility, resemblance to civilian vehicles, and ability to deploy heavy weapons was used to devastating effect by the Islamic State during the 2014 Fall of Mosul. Striking quickly while Iraqi national tanks were deployed elsewhere the small Islamic force entered the city at 2:30 am, striking in small convoys that overwhelmed checkpoints with their firepower, executing and torturing captured Iraqi soldiers and targeted enemies as they went. Even after taking into account desertions and “ghost soldiers” (fake soldiers meant to pad unit numbers so corrupt officials could collect their pay) which significantly reduced the 30,000 Iraqi army and 30,000 police within the city … Even after allowing for all that, the Iraqi national forces still outnumbered the 800-1500 ISIS fighters at a rate of 15 to 1.

YET ISIS was able to achieve a total victory and take the whole of the city within 6 days.

2 years later it would take the Iraqi government with American backing 9 months to retake it.

How? How does a force of 1500 at most, most without any formal training, overwhelm and defeat a force of 12,000-23,000, which at least has some training, better equipment, and has an entire state behind it? How did ISIS do this entirely without air support? Even as the Iraqi government bombed them from helicopters?

How did they take in 6 days what would take the Iraqi government with full American backing 9 months to retake?

Well, they made the Iraqis break and run.

January 21, 2024

The Duke of Wellington, perhaps best known as the inventor of the Wellington boot …

Weaver Sheridan expresses some surprise that His Grace’s main source of fame is the credit for the invention of the Wellington, rather than his other, uninteresting achievements:

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington (1769–1852) by Thomas Lawrence, circa 1815-1816.

Wikimedia Commons.

I know nothing should surprise us these days about dumbed-down Britain. But an article on the moronic Mail Online website the other day had me choking on my cornflakes.

It read: “In 2020, Mandy Lieu, 38, bought 935-acre Ewhurst Park in Hampshire, once owned by the inventor of the wellington boot, the Duke of Wellington, and vowed to turn it into a world-class organic farm and nature reserve.”

The inventor of the wellington boot!

Good grief, I know teaching of British history is nowadays outrageously skewed and bowdlerised, but I didn’t realise things had got this bad.

The article’s author obviously thinks the Iron Duke’s main claim to fame was the welly. Does she know nothing about him being a soldier and statesman, victor of the Peninsular War, victor of Waterloo, nemesis of Napoleon, twice Prime Minister? Or is the wellington boot reference made simply to get equally thick readers to relate to the story? Who cares about fusty old battles and boring politics? It is all so yesterday, isn’t it? But everyone knows what wellies are, don’t they?

To anyone with a modicum of interest in this country’s past, such ignorance is deeply depressing, to say the least. But I suppose it could be worse. Think what would happen if some Mail Online know-nothing hack was able to interview other historical figures …

“Sir Winston Churchill, tell us how you came up with the idea of a nodding bulldog to promote your insurance company.”

“Napoleon, having invented a popular type of brandy, was it perhaps rather egotistical to name it after yourself?”

“Pablo Picasso, as a car designer you must be thrilled to see your Citroën Grand C4 Picasso being crowned “Best Used MPV” in the Auto Express Used Car Awards 2023.”

January 20, 2024

QotD: 19th Century techno-optimism

In The Politics of Cultural Despair (a book I recommend, with reservations), Fritz Stern called the writers of the 19th century “conservative revolution” in Germany “intellectual Luddites”. Just as the original Luddites wanted to stop “progress” by breaking machines, so the intellectual Luddites wanted to un-enlighten the Enlightenment, wiping out “Manchesterism” to return to a largely imaginary communitarian, agrarian past. The “machine” the intellectual Luddites sought to break, Stern argues, was reason … or, at least, rationalism, which by the later 19th century was basically the same thing in most people’s minds.

They had a point, those intellectual Luddites. If you haven’t read up on the later 19th century in a while, it’s almost impossible to convey their boundless optimism, their total faith that “science” could, would, and should solve every conceivable problem. The best I can do is this: Back when they were still allowed to be funny, The Onion published a book called Our Dumb Century, which purported to be a collection of their front pages from every year of the 20th century. The headline for 1903 was something like: “Wright Brothers’ Flyer Goes Airborne for 30 Seconds! Conquest of Heaven Planned for 1910.”

That’s the late 19th century, y’all.

Severian, “Digital Infants”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-04-16.

January 6, 2024

Inside Mark I: The First Fighting Tank

The Tank Museum

Published 15 Sept 2023The first ever use of the tank in battle happened during the Battle of the Somme in 1916. In this video we look inside a unique survivor – the last British Mark I Heavy Tank in existence and examine the first tank action at Flers, an event that changed the face of warfare.

(more…)

December 11, 2023

This man built his office inside a lift

Tom Scott

Published 28 Aug 2023The Baťa Skyscraper, in Zlín, Czechia, is a landmark of architecture. And the office of Jan Antonín Baťa … is an elevator.

Thanks to the museum staff for fact-checking and translation!

(more…)

December 10, 2023

The history of the steam engine … but interactive

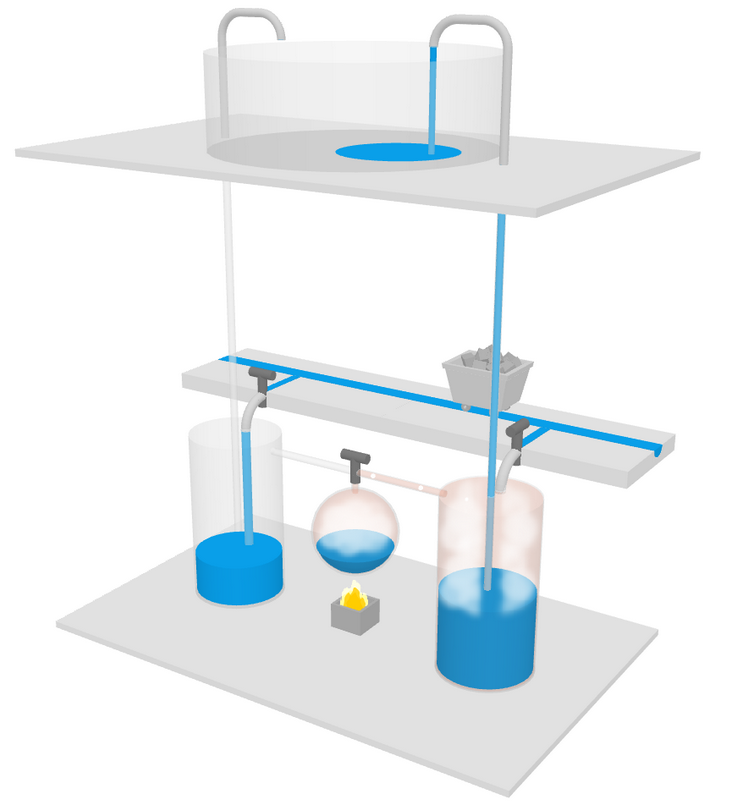

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes is pleased to announce the release of a new ongoing project to illustrate the steam engine in an interactive format:

I’m excited to announce something I’ve been quietly working on for a few months now behind the scenes. Some of you may be familiar with the explorable interactive articles of Bartosz Ciechanowski. They are so clearly written and so cleverly explorable, that they give an intuitive grasp of how many very complicated technologies work. My favourite is his article on mechanical watches. Be warned: if you’ve not seen these before, you’re about to lose a good few hours.

But his article on watches — which came out just as I was doing some research on the development of watches, and which proved an invaluable reference work — got me thinking about how great it would be to have something similar not just for how current technologies function, but to show how they changed over time. Wouldn’t it be great, I dreamed, to have a similarly intuitive way to explore and appreciate the process of improvement. And to correct lots of misapprehensions about the development of various technologies along the way.

As it turned out, my fellow inventions history fanatic Jason Crawford, who runs the non-profit The Roots of Progress, had been thinking along the same lines. (Drumroll starts softly.) So with the help of the Matt Brown we’ve been able to realise what is hopefully just the first small step of our vision. (Drumroll intensifies.) Based on my recent work re-writing the standard pre-history of the steam engine (drumroll crescendoes), allow me to present:

(Cue trumpets!)

The interactive, animated, **Origins of the Steam Engine**

Alongside contemporary illustrations of the many devices, you can play around with the animated models, dragging them to see them from different angles. It introduces what are so far the only interactive and animated models yet made of a great many devices — from Philo of Byzantium’s 3rd Century BC experiments, to Salomon de Caus’s 1610s solar-activated and self-replenishing fountains and musical instruments, and the 1606 steam engine of the Spanish engineer Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont:

It also contains the first depictions of the 1630s and 40s devices of Kaspar Kalthoff and William Petty. These are the experiments I discovered about a year ago, which I hope will now be given a place in the canon of the history of the steam engine. (You can read my discussion of the evidence I’d stumbled across about them here.)

December 5, 2023

See Inside Sherman Firefly | Tank Chats Reloaded

The Tank Museum

Published 1 Sept 2023Inspired innovation or a bit of a lash-up? In this video we look inside the legendary Sherman Firefly, the British Army’s Tiger killer. We also hear from a Firefly veteran, Ken Dowding, ex-14th/20th Hussars.

(more…)