Forgotten Weapons

Published 11 Dec 2020http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

https://www.floatplane.com/channel/Fo…

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

Possibly the coolest small arm used by the United States in the Vietnam War was the China Lake 40mm pump action grenade launcher. Only 24 of these were made, each fitted by hand. Of those, 2 went to MACVSOG, 2 to Army Force Recon, and the remaining 20 the the Navy SEALS. They were used as an ambush initiation weapon, with 4 rounds of rapid-fire 40mm HE grenades available.

Only five original examples survive today; four in US museums and military institutions and one in a museum in Saigon. An effort was made in 2004 to build reproductions, it is one of those used in this video. This project was not ultimately successful, but did lead to a very interesting series of events with the Airtronic company and the US Marine Corps, which will be detailed in a following video. Special thanks to Dutch Hillenburg and Kevin Dockery for making this video possible!

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

6281 N. Oracle #36270

Tucson, AZ 85740

March 14, 2021

China Lake 40mm Pump Action Grenade Launcher

March 8, 2021

The Rise of Artillery in European Siege Warfare

SandRhoman History

Published 7 Mar 2021Get 25% off an annual membership of CuriosityStream using code

sandrhoman: https://curiositystream.com/sandrhomanAt the end of the Middle Ages, a new weapon system changed the face of 15th century European siege warfare: artillery made its appearance. It had an impressive impact best shown by one peculiar fact. Imagine a walled fortress in the 14th century. It could easily deter attackers for several months. But in the early 15th up to the early 16th century, after artillery had fully developed, the same walls fell within days. As a result, engineers had to construct much more elaborate defensive structures. By the early to mid 16th century a fortress could again withstand a siege with heavy artillery for several months. This is how modern historiography explains the rise of artillery.

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/sandrhomanhis…

Bibliography:

Ayton, A., / Price, J. L., (Hrsg.), The Medieval Military Revolution. State, Society and Military Change in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, 199J.

Black, A Military Revolution? Military Change and European Society 1550–1800, 1991.

Devries, K., Medieval Military Technology, 1994.

Ortenburg, G., Waffe und Waffengebrauch im Zeitalter der Landsknechte (Heerwesen der Neuzeit, Abt. 1, Bd. 1) Koblenz 1984.

Rogers, C. J., “Military Revolutions of the Hundred Years War”, in: Rogers et al. The Military Revolution Debate. Reading on the Military Transformation of Early Modern Europe, 1995, p. 13-35.

Schmidtchen, V., Kriegswesen im Spätmittelalter, 1990.

M79: The Iconic “Bloop Tube” 40mm Grenade Launcher

Forgotten Weapons

Published 4 Dec 2020http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

https://www.floatplane.com/channel/Fo…

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

Combat experience with the bazooka rocket launcher in World War Two and its larger versions in the Korean War convinced the US military that a better weapon was needed to give front-line troops a direct-fire way to attack enemy strong points. The bazooka was bulky, not particularly accurate, and created a lot of backblast signature when fired. This led to a multi-part development effort involving design of a small grenade body, reliable but cheap fusing system, and a cartridge design that could launch it.

The result was the 40x46mm grenade. It uses a “high-low” system (originally developed by Rheinmetall during World War Two) in which a powder charge is fired in a small compartment within the cartridge case. The initial pressure in this compartment is some 35,000 psi, which is plenty high to ensure complete and repeatable powder burn. At peak pressure, the internal compartment ruptures, allowing the propellant gasses to expand into the full case volume, which lowers the pressure to about 3,000 psi. This lower pressure is safe to use with an aluminum barrel, and propels the grenade at about 250 fps, giving it a range of about 400 yards without generating excessive recoil.

The M79 proved to be very accurate and reliable. Its downside was the need for the grenadier to carry a backup sidearm, as the M79 could not be used at close range. Almost as soon as it was introduced, work began on developing a launcher which could be attached to the M16 service rifle. This would first be the XM-148, and then ultimately the M203 that would replace the M79 in service. M79 launchers can still be found all over the world, however, as they are robust and reliable.

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

6281 N. Oracle #36270

Tucson, AZ 85740

March 2, 2021

The Evolution of Shock Cavalry – From Antiquity to the Middle Ages

Invicta

Published 1 Mar 2021Learn about the evolution of shock cavalry from antiquity before the use of saddles and stirrups! Check out The Great Courses Plus to learn about shock cavalry in the campaigns of Alexander the Great: http://ow.ly/osex30rvhjf

In this history documentary we explore the topic of ancient cavalry. The basic idea is that these units often get depicted in media as performing glorious massed charges headlong into the enemy ranks as seen in such scenes as the Charge of the Rohirrim from the Battle of Pelenor Fields. In reality this would have been a very dangerous situation for cavalrymen even under the best circumstances. But to make matters worse, riders from antiquity fought without the use of either saddles or stirrups. So how on earth did they manage to dominate the battlefield with these handicaps. Let’s find out.

We begin by covering the history of cavalry with the first domestication of the horse and its introduction to warfare first as member of the baggage train and soon after as a part of chariot crews rather than as actual mounted forces. This was in large part due to the lack of riding experience and technology on behalf of the rider. Soon after the Bronze Age Collapse however cavalry began to rise to prominence across the armies of the Mediterranean. We speak about the various forms of equine practices which ranged from riding bareback into combat as with the Numidian Cavalry to the use of simple bridles and cloth seats as with Greek Cavalry and Persian Cavalry.

We then cover the techniques used by these cavalrymen to mount, ride, and fight. As a part of this discussion, we rely heavily on Xenophon’s Manual on Horsemanship which provides excellent first hand details from the period. We also show how these techniques were successfully used by shock cavalry of antiquity such as the Macedonian Companion Cavalry, the Saka Steppe Lancers, and the Persian Cataphracts to great effect even without the use of saddles and stirrups.

Finally we do pose the question of why they didn’t use the saddle and stirrup given its seemingly obvious advantages. To answer this question we look at the history of its development from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages.

Bibliography and Suggested Reading

On Horsemanship, by Xenophon

Adrian Goldsworthy, The Complete Roman Army

Adrian Goldsworthy, Roman Warfare

J.C. Coulston, Cavalry Equipment of the Roman Army in the First Century A.D.

George T. Dennis, Maurice’s Strategikon, p. 38.

Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Civili

Russel H. Beaty, Saddles#History

#Documentary

#ShockCavalry

From the comments:

Invicta

13 hours ago

I was inspired by comments on our latest Units of History episode covering the Companion Cavalry which asked about how shock tactics worked in an age before the stirrup and saddle. I went down the rabbit hole finding answers and present to you my findings in this video! One awesome source we used was the Manual on Horsemanship by Xenophon which you can read for yourself here: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1176/1176-h/1176-h.htm

Tank Chats #97 | Panzer II | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 20 Mar 2020Here David Willey discusses the Panzer II, a German tank which was instrumental in the early days of the Second World War, especially during the Blitzkrieg.

Support the work of The Tank Museum on Patreon: ► https://www.patreon.com/tankmuseum

Visit The Tank Museum SHOP: ►tankmuseumshop.org

Twitter: ► https://twitter.com/TankMuseum

Instagram: ► https://www.instagram.com/tankmuseum/

Tiger Tank Blog: ► http://blog.tiger-tank.com/

Tank 100 First World War Centenary Blog: ► http://tank100.com/

#tankmuseum #tanks

February 25, 2021

Tank Chats #96 | D3E1 Wheel-cum-Track Machine | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 28 Feb 2020David Fletcher looks at the experimental inter-war Vickers D3E1, which was conceived to solve the problem of track wear, with wheels that could be used instead where the ground was suitable. In practice the concept proved too complicated.

Support the work of The Tank Museum on Patreon: ► https://www.patreon.com/tankmuseum

Visit The Tank Museum SHOP: ►tankmuseumshop.org

Twitter: ► https://twitter.com/TankMuseum

Instagram: ► https://www.instagram.com/tankmuseum/

Tiger Tank Blog: ► http://blog.tiger-tank.com/

Tank 100 First World War Centenary Blog: ► http://tank100.com/

#tankmuseum #tanks

February 21, 2021

Missing the point of the 1851 Great Exhibition

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes explains why the 1951 Festival of Britain failed to reproduce the success of the Great Exhibition of a century earlier, even though it did succeed in other ways:

The Crystal Palace from the northeast during the Great Exhibition of 1851, image from the 1852 book Dickinsons’ comprehensive pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851

Wikimedia Commons.

… the idea that I tend to get most excited about, which I mentioned only in passing last month, is how we might resurrect the spirit of the nineteenth-century exhibitions of industry.

The best-known of these is undoubtedly the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations of 1851, still famous for its Crystal Palace. Held in Hyde Park, London, it attracted six million visitors, and has been emulated many times since. The World Fairs of today number the Great Exhibition as their first. Yet most people today don’t really appreciate what the Great Exhibition was actually for. They see it as a big, international event, with millions of visitors, who saw all sorts of fancy and exciting things — a chance for Britain, and many other countries since, to show off. The result is that many of the events that seek to capture something of the spirit of the original exhibition — 1951’s Festival of Britain, most of the World Fairs since the Second World War, the Millennium Experience, the 2018 Great Exhibition of the North, and now an upcoming “definitely-not-a-Festival-of-Brexit” (currently branded as Festival UK* 2022) — totally and utterly miss the point.

This is perhaps best illustrated by the runup to the 1951 Festival of Britain. Its proposers in the 1940s saw that the centenary of the Great Exhibition was coming up, so they proposed that there should be something similar to mark it. Yet by doing so, they did things entirely back-to-front. The Great Exhibition had a purpose; the exhibition was just the medium. It was the tool for a specific and sophisticated agenda. The Festival of Britain, by contrast, started with the idea of an exhibition, and then flailed about for a reason why. The government had a vague idea of organising an event to lift the country’s spirits after the Second World War, as well as to have it Britain-focused so as to craft a new national identity as the old empire disintegrated. But as its director-general Gerald Barry put it when they actually started work on the event: “we sat before our blotting pads industriously doodling, in the hope perhaps that a coherent pattern might eventually emerge, on the same principle that if you set down twelve apes before twelve typewriters they will (or so it is said) in the course of infinity type out the complete works of Shakespeare.”

Looking at the build-up to Festival UK* 2022, it’s hard not to get the same impression. The government wanted something to vaguely help craft a post-Brexit identity, on which it is happy to spend well over a hundred million pounds. Yet to make it happen it has funded a “research and development” project: a whole bunch of committees tasked with coming up with ideas of what to actually do (so far, it’s to be “a collection of ten large-scale, public engagement projects”). This is not to say that the event won’t, in some sense, succeed. The 1951 Festival of Britain, after all, was widely lauded. Barry’s twelve apes at their typewriters didn’t quite write Shakespeare, but they did manage to come up with something that many people remembered fondly. Perhaps some of the projects in 2022 will be similarly impressive.

Yet that doesn’t change the fact that the more recent projects miss the point. In fact, I’d say they are the exact inverse of the Great Exhibition. For a start, the 1851 event was entirely self-funded. It had government support, of course, including a cross-party Royal Commission to oversee the team that did the day-to-day running of things, but it raised its money through a public subscription and, when this was insufficient, took out a loan backed by a group of wealthy guarantors. Fortunately, the guarantors never had to pay out, as the event made so much through ticket sales that it was wildly profitable — so much so that the Royal Commission for the Great Exhibition of 1851 still exists. It purchased the 87 acres of land immediately south of the exhibition site, at South Kensington, for a more permanent collection of cultural institutions including many of London’s major museums. It helped fund a subsequent exhibition of industry on that site in 1862 — which actually had even more visitors, though it’s hardly remembered today. And even now, the Royal Commission continues to dispense over £3m every year to students and researchers.

That self-funding was important, I think, because it removed one of the main criticisms faced by modern large-scale events: that they are expensive wastes of taxpayer money on the vanity projects of politicians. The crowd-funding and finding of sufficient guarantors meant that the event needed to be accepted by the public at large, and even had them committed to the project before it had even begun. It necessitated a clear, exciting message from the get-go, rather than a post-hoc rationalisation.

And what was that message? For nineteenth-century organisers, an exhibition of industry was not just some grand display with a certain je ne sais quoi. It was intended as an engine of improvement: a direct way to actually encourage invention rather than just celebrate it, to raise the standards of consumers, and to lower barriers to trade. It was even a tool of industrial policy, and a springboard for reform.

February 15, 2021

Gewehr 71/84: Germany’s Transitional Repeating Rifle

Forgotten Weapons

Published 10 Jun 2018http://www.forgottenweapons.com/geweh…

http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

In the ongoing arms race between France and Germany, the Mauser 71/84 was the first German repeating rifle. Paul Mauser began work on it in the late 1870s, patented the design in 1881, and it was adopted formally in 1884. Production began in 1885, with a total of 1,161,148 rifles being delivered by the four major state arsenals (Spandau, Amberg, Erfurt, and Danzig) by 1888 — when it was replaced by the Gewehr 88. With an 8-round tube magazine under the barrel, the 71/84 represented a substantial increase in firepower over the single-shot Mauser 71 and the French 1874 single shot Gras — but it was put into production just in time to be rendered obsolete by the Lebel and its smokeless powder cartridge in 1886.

The 71/84 was perhaps the German rifle with the shortest service life, at barely 5 years. It would come back out as a reserve rifle during World War One, of course, and it also was responsible for a change in German arms that would last all the way to the present day — the pull-through cleaning kit. The tubular magazine made it impossible to leave a cleaning rod under the barrel as on the Gew71, and rather than put it on the side like the French and Portuguese, Germany opted to remove it entirely in favor of the then-new pull-through cleaning kit.

If you enjoy Forgotten Weapons, check out its sister channel, InRangeTV! http://www.youtube.com/InRangeTVShow

February 14, 2021

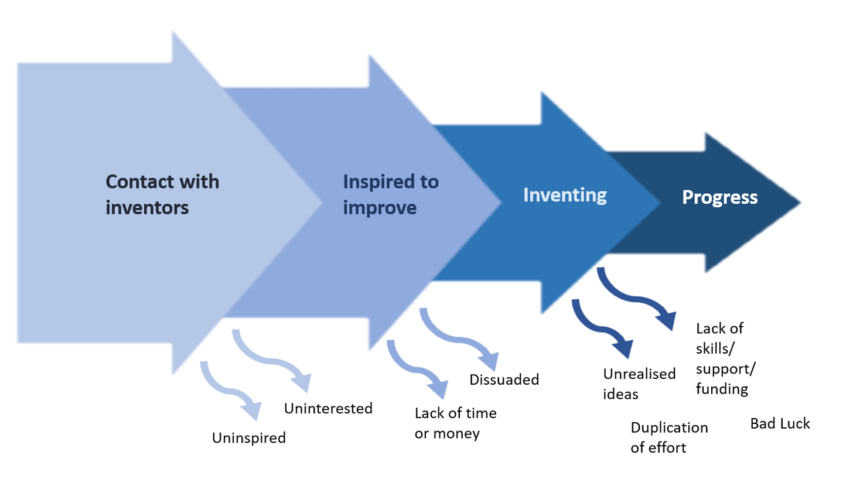

Helping to make more innovators

In the most recent Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers what “spark” seems to be needed to get people to think of innovations and how it can be done — albeit less efficiently — by reading about innovators or for more modern audiences, watching movies:

As I mentioned last time, increasing the supply of people becoming inventors is possibly one of the most significant, world-changing things that anyone can do. So I’ve been thinking a lot lately about what I call upstream policies: things that expose people to the idea of invention, increasing the chances that they themselves will be inspired with an improving mentality — a mindset of seeing problems where others do not, and then developing solutions to them. Contrary to “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”, the inventor is the person who can’t help but see the extra potential to improve things, and can’t resist applying their fixes too.

During the Industrial Revolution, most exposure to invention seems to have been face-to-face. There are a handful of cases where reading about inventors may have played a role in inspiring some people to invent. John Harrison, the clockmaker who created a timepiece so advanced that it allowed sailors to find their longitude even at sea, was allegedly given a copy of the scientific lectures of Nicholas Saunderson by a visiting clergyman when he was just a boy. (Whether it was the book or really the clergyman who inspired him, however, it is difficult to say.) Likewise, Francis Maceroni, an early nineteenth-century pioneer of kite-surfing, who also applied himself to improving swimming, paddle wheels, rockets, asphalt paving, and steam carriages, among other things, seems to have first been exposed to innovation by reading various books on science, including the works of Benjamin Franklin. Or take the young George Stephenson, pioneer of railway locomotion, who read a history of inventions that apparently prompted him to try to invent a perpetual motion machine (before another book, this time on mechanics, revealed to him the error in trying).

Inspiration can be indirect, with the written word complementing face-to-face interactions, or even prompting them to seek them, as well as giving people a taste of the improving mentality. I suspect that books like Samuel Smiles’s bestseller Self Help — essentially a collection of pulled-themselves-up-by-their-bootstraps stories about inventors — played a part in inspiring people to also have a go at improvement in the late nineteenth century, a little after the period I mainly study.

Today, however, we have many more media available to us to encourage people to become inventors — from radio and film, to video games and various other kinds of social media. Yet I’m not sure we’re doing it all that well. As I mentioned last time, I’ve been working my way through a bunch of the films that were suggested to me (the list is here), and so far I have largely been disappointed.

February 11, 2021

Tank Chats #94 | Kettenkrad and Springer | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 31 Jan 2020Here David Willey examines two WW2 German tracked vehicles. The first is the Sd.Kfz. 2, better known as the Kettenkrad, a light tractor. The second, the Springer, a demolition vehicle which was fundamentally a mobile bomb, which shared the Kettenkrad’s running gear and engine.

Support the work of The Tank Museum on Patreon: ► https://www.patreon.com/tankmuseum

Visit The Tank Museum SHOP: ►tankmuseumshop.org

Twitter: ► https://twitter.com/TankMuseum

Instagram: ► https://www.instagram.com/tankmuseum/

Tiger Tank Blog: ► http://blog.tiger-tank.com/

Tank 100 First World War Centenary Blog: ► http://tank100.com/

January 26, 2021

Tank Chats #92 | Challenger 2: Part 2 | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 17 Jan 2020Part 2 of a two-part episode on Challenger 2 [part 1 was posted here]. As David Willey had so much to say about this British in-service vehicle, it has been split into two parts. The second part examines the Challenger 2 in service. David talks to soldiers currently serving on the Challenger 2, looks at where it has seen service and some of the tank’s features. With thanks to the British Army for their assistance.

Support the work of The Tank Museum on Patreon: ► https://www.patreon.com/tankmuseum

Visit The Tank Museum SHOP: ►tankmuseumshop.org

Twitter: ► https://twitter.com/TankMuseum

Instagram: ► https://www.instagram.com/tankmuseum/

Tiger Tank Blog: ► http://blog.tiger-tank.com/

Tank 100 First World War Centenary Blog: ► http://tank100.com/

#tankmuseum #tanks #challenger2 #britisharmy #davidwilleytankchat #davidwilleychallenger2

QotD: “A world organized around institutional mass slavery”

An example: We’ve discussed all the cool steampunk shit the Greeks could’ve had, if only Archimedes had … well, that’s just the thing, isn’t it? We look at the aeolipile and see a prototype steam engine; they looked at it and saw, as best we can tell, a party trick. Back when, I suggested, Marxist-style, that labor costs were a sufficient explanation for why nobody took the obvious-to-us next step of hooking the thing up to something productive and kicking off the Industrial Revolution. Machines are labor-saving devices; the ancient world had a gross excess of labor. Calling the aeolipile a steam engine, then, is a category error.

New hypothesis: It’s a category error, all right, but not because they didn’t think in terms of labor costs. It’s because they couldn’t think in terms of labor costs.

A world organized around institutional mass slavery is, in a very real sense, a timeless world. Herodotus (I think) actually says somewhere that nothing worth mentioning happened before him, and you can see echoes of this attitude even as late as the Antebellum South. You see their attitude described as “conservative,” but since that’s egghead shorthand for “evil” you can ignore it. They weren’t consciously backward-looking; rather, they were deeply rooted to their place and station. To the outsider, it looked like they were trying to hold time back, but to the insider, time — clock time, industrial time, the time of the Protestant work ethic — barely existed at all.

So with the Classical World. The Romans, for instance, are endlessly frustrating to their admirers (of which I am an ardent one). Their only economic fix, for instance, was debasing the currency, i.e. a primitive form of inflation. You guys could figure out how to hew an artificial harbor out of some desert rocks — a trick we’d have a hard time pulling off today — but you couldn’t figure out fiat currency? Or a better political system than the tetrarchy? Or that the forts-and-legions paradigm just isn’t cutting it? Or … etc.

Stuff like that is why Spengler said classical, Apollonian culture was fundamentally different from, and incompatible with, our Faustian culture. According to Spengler, the master metaphor for the Apollonian is the human body, which is beautiful but changeless (emphasis mine, not Spengler’s). You can improve your body somewhat, but only within certain tight limits, and the body’s fundamental form is always the same (we could time warp Julius Caesar into the Current Year and still recognize him as a fellow homo sap., no matter how different his mind might be).

The Faustian, though — that would be us — organizes his worldview around space, infinite space. Practically speaking, this results in our attitude of innovation-for-innovation’s sake. We send a man to the moon because we can, but such an idea would never occur to the Romans, for the same reason they didn’t apply all their awesome engineering knowledge to the problems of governance. Hacking a harbor out of the desert is a tremendous feat, but it’s a local feat — a one-shot deal, a very specific response to a very specific local problem, with no broader applications.

This, I suggest, is because the timeless world of institutional mass slavery naturally selects for the kind of man who is at home in the world of institutional mass slavery. It’s a world of very low future time orientation, because “time” hardly exists at all. Forget machinery for a sec; the Roman world was full of enormous problems that had teeny-tiny, head-slappingly obvious fixes. Julius Caesar, for instance, was considered some kind of prodigy because he could sight-read books. Which really was a noteworthy feat, because Romans didn’t even put spaces between their words, much less use any sort of punctuation marks. And they were radical innovators compared to the Ancient Egyptians, since at least Roman writing all ran left-to-right; hieroglyphics can be read in any direction, including vertically, and I’m pretty sure there are examples of them changing text orientations in the middle of the same inscription. It’s not hard to imagine some legion commander actually losing a battle because he had to stop and sound out an important communique from a subordinate …

… and yet the Romans, for all their technical skill, never even figured that tiny change out. See also: The Chinese doing fuck-all with movable type, vs. (Faustian) Europeans using it to conquer the world. China, too, was a timeless society. As Derb says somewhere, Classical Chinese isn’t even really writing; it’s more of an aide-memoire — designed to remind readers of stuff they already know, not to communicate new information.

Your post-Roman European, by contrast, lived in a world where high future time orientation was an absolute must. You don’t need hypotheses like the famous “lead in the drinking water pipes” to explain the seemingly bizarre things the Romans did, or didn’t do; all you need is time orientation, a fundamental attitude of “this is a variation on an old problem” vs. “this is an entirely new situation that requires a new response.” Life in the post-Roman world was solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short — every man for himself; think through the consequences of your actions very carefully before you do them, or die horribly. Those who failed to do so died. Bake that into the genetic cake for a few generations, and you get Renaissance Man, who’d see a million possible applications for the aeolipile.

Severian, “Bio-Marxism”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-09-24.

January 23, 2021

Innovation is infectious … you catch it from other innovators

An interesting notion on how people innovate or invent is discussed in Anton Howes’ latest Age of Invention newsletter:

… my research on the Industrial Revolution has yielded a general model of how to think about it.

Core to the model is the observation that innovation spreads from person to person. It is a mentality, that we pick up from others. Of my sample of inventors, active c.1550-1850, the vast majority of them had had some kind of contact with an inventor before inventing anything themselves. So far, I’ve found evidence of that contact for about 83% of them, and for the remainder we frankly know next to nothing about them anyway. On the balance of probability, I suspect that all inventors had and continue to have such prior contact, even if the evidence has been lost to the mists of time.

Supposing I’m right about this — and there’s also more recent evidence from the largest and most detailed ever study of modern American inventors to support it — then such exposure to an inventor is the ultimate cause of innovation. Everything else we worry about when promoting innovation, from funding to intellectual property rights, or from education to social acceptance, is in a sense downstream of it.

Absent any exposure to inventors, people simply don’t become inventors. Knowing about invention as an activity is a necessary precondition to becoming an inventor yourself. The vast majority of people never innovate, for the very simple reason that it never occurs to them to do so. People are faced with problems all the time, but they generally have all sorts of pre-existing responses to them. Famine? The millennia-old response was to tighten belts or starve. Not to try to innovate with agricultural techniques. Trade route collapse? The millennia-old response was to take the hit, or try to shift to other familiar markets. Not to try to send ships into the icy unknown. As I’ve noticed time and time and time again, necessity is not the mother of invention. It only appears that way in retrospect — it’s when faced with a crisis that pre-existing inventors step forth to solve problems in ways they had already been investigating. Without them, there would be no such innovative response. Crises have an effect on the direction of invention — that is, on what problems people identify and then try to solve — but not on its underlying supply.

But this is not to say that exposure to an inventor is sufficient. Supposing you do meet an inventor. Your contact might be too fleeting to have an impact, or you might not be predisposed to be inspired by them. You might lack curiosity, or be distracted by some other preoccupation. Or perhaps the inventor you met might not be an especially inspiring person. Some people are simply more interesting than others. So from an initial spring of people who come into contact with inventors, we can immediately narrow the flow of new inventors down to those for whom such exposure actually had an impact.

But we then have to narrow it down further. Of the people who have met an inventor and been inspired by them, some might be distracted by other activities, or be dissuaded by social barriers, or lack the resources to tinker around with things, whether it be money or time.

January 20, 2021

Tank Chats #92 | Challenger 2: Part 1 | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 20 Dec 2019Part 1 of a two-part episode on Challenger 2. As David Willey had so much to say about this British in-service vehicle, it has been split into two parts. This first part looks at the design and development of Challenger 2. With thanks to the British Army for their assistance.

Challenger 1 video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lwcx7…

Support the work of The Tank Museum on Patreon: ► https://www.patreon.com/tankmuseum

Visit The Tank Museum SHOP: ►tankmuseumshop.org

Twitter: ► https://twitter.com/TankMuseum

Instagram: ► https://www.instagram.com/tankmuseum/

Tiger Tank Blog: ► http://blog.tiger-tank.com/

Tank 100 First World War Centenary Blog: ► http://tank100.com/

#tankmuseum #tanks

January 8, 2021

Renault’s Backwards Car

Big Car

Published 12 Oct 2020Renault’s Project 900 is certainly an odd-looking car, but it’s also a car designed to break new ground. It used innovative new materials and gave class-leading visibility to try to leapfrog the competition. It also seems they were trying to beat their competition in the “weird” category as well, which given they were up against Citroën was no mean feat! So, what happened to Renault’s backwards car, and what echoes of this strange but innovative design are there in today’s cars?

To get early ad-free access to new videos, or your name at the end of my videos, please consider supporting me from just $1 or 80p a month at https://www.patreon.com/bigcar

Link to my second channel – Little Car: https://www.youtube.com/littlecar

Get Big Car t-shirts, mugs or a tote bag at teespring.com/stores/bigcartv

#bigcar