Last Sunday was the 100th anniversary of the first major naval victory of the Royal Australian Navy, when Australian light cruiser HMAS Sydney fought against one of the Kaiser’s most effective commerce raiders, SMS Emden in the Indian Ocean:

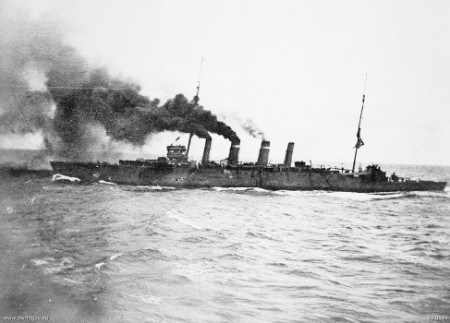

November 9 is when the light cruiser HMAS Sydney met the light cruiser SMS Emden in action in the Indian Ocean, dispatching a surface raider that had taken a heavy toll on Allied merchant and naval shipping since the guns of August rang out. R. K. Lochner chronicled Emden’s exploits in the late 1970s, dubbing her “the last gentleman of war.” Lochner awarded the cruiser this title to acknowledge skipper Karl von Müller’s and his crew’s scrupulous fidelity to the laws of cruiser warfare. The Germans’ enemy paid homage to Emden’s gallantry as well. Two days after the engagement, for instance, the London Daily News saluted the “resourceful energy and chivalry” displayed by the raider’s crewmen throughout their voyage. That, of course, was an era when knightly conduct was in decline on the high seas, yielding to unrestricted submarine warfare. Striking without warning, as U-boats commonly did in the Atlantic, left mariners and passengers scant prospects of escaping an attack.

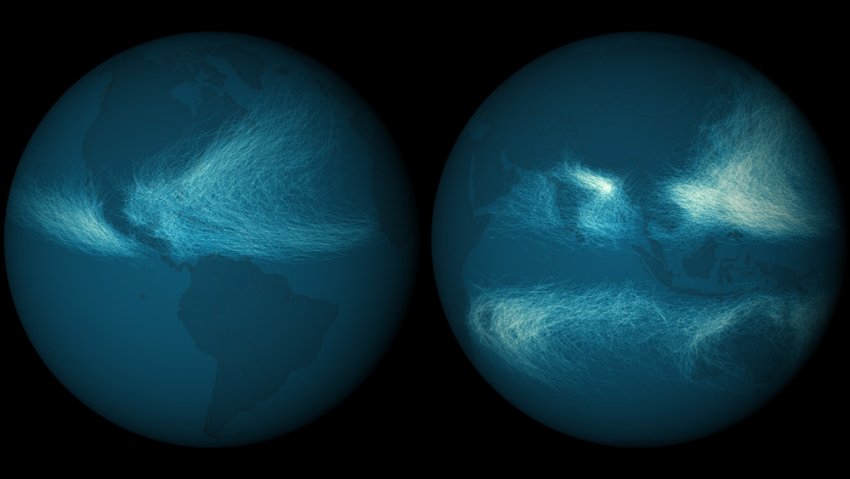

The battle, then, helped mark the passing of an age. Emden had remained behind at the onset of war, after the German East Asian Squadron quit Southeast Asia to return home. Hers was not destined to be a prolonged cruise. Cut off from logistical and maintenance support, Captain Müller had to forage for coal and stores. The cruiser coped with this hand-to-mouth existence — for a while — and in the process sank or captured twenty-five merchantmen, destroyed two Allied men-of-war at Penang, and bombarded the seaport of Madras, along the seacoast of British India. That’s quite a combat record. It’s especially noteworthy when compiled by seafarers who were unsure where they could refuel next — if anywhere at all — and were sure that equipment that suffered a major breakdown would never be repaired for want of spare parts and shipyard expertise.

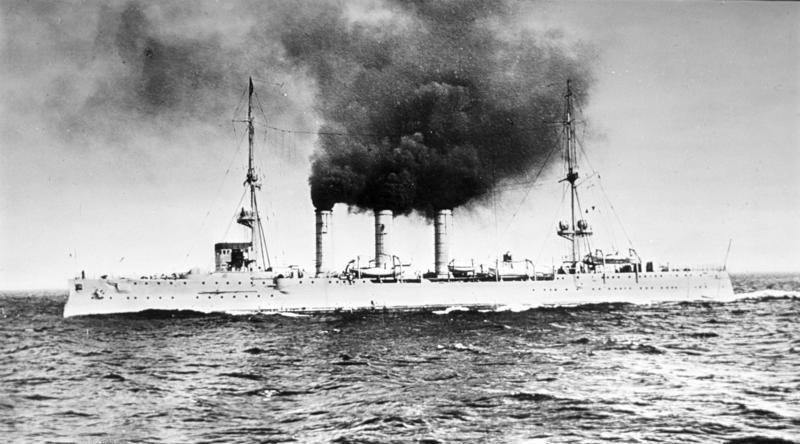

The light cruiser HMAS Sydney steams towards Rabaul. The Australian Naval & Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF), which included HMAS Sydney, HMAS Australia, HMAS Encounter, HMAS Warrego, HMAS Yarra and HMAS Parramatta, seized control of German New Guinea on 11 September 1914 (via Wikipedia)

No ship can keep going for long without putting into port or tapping resources from nearby fuel or stores ships. Heck, U.S. Navy commanders — like their counterparts in other fleets, no doubt — get antsy when the fuel tanks drop to half-empty or hardware fails at sea, hampering performance or reducing redundancy in the propulsion plant or other critical machinery. And that’s in a navy accustomed to having logistics vessels steaming in company to top off the tanks, replenish stores, or transfer or manufacture spares when need be. Imagine being altogether alone in some faraway region — at risk of running out of some vital commodity or suffering battle damage and finding yourself dead in the water. Such loneliness and doubt were constant companions to Emden officers and men during the fall of 1914.It takes extraordinary pluck to seize the offensive amid such circumstances. And yet the Germans did. In November, nonetheless, Sydney found Emden in the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, where Müller had decided to attack a communications station that was aiding the hunt for his raider. Like so many naval actions, it was a chance encounter. The station got off a distress call, and Sydney — which happened to be in the vicinity while helping escort a convoy transporting Australian and New Zealand troops to Europe — responded to it. Emden gave a good account of herself, landing several punches before Sydney’s heavier main guns began to tell. Hopelessly outgunned, Müller ultimately ordered his vessel beached on North Keeling Island to save lives. Of the crew, 134 seamen fell while 69 were wounded and 157 were captured.