Colby Cosh, after taunting Ontarians yet again over our just-barely-past-Prohibition views on alcohol in public places, goes on to praise the work of UCLA economist Donald Shoup and his insights into the economics of parking:

“Parking meter FAIL” by kingdesmond1337 is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

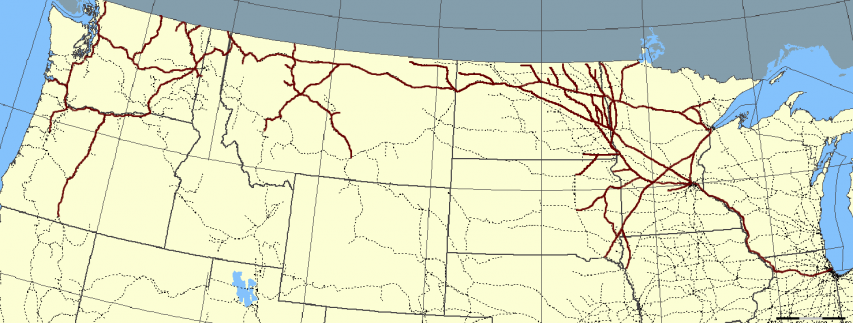

Parking — boring topic, ain’t it? Shoup latched onto it as a young-ish man because he was a follower of Henry George (1839-1897), the intriguing “single tax” economic theorist of the 19th century. George favoured a tax on the unimproved value of land parcels as a way of socializing pure rent (the value earned from occupying a mere location) and encouraging development. It is a concept that many economists still like, although it is potentially difficult to apply at scale. The widely used concept of tax increment financing is one example of Georgism in practice.

Shoup started out trying to fit parking spaces into the Georgist picture, but the boring topic was so underexamined that he found himself having to build a general theory of parking. He quantified the relationship between parking and traffic, finding that people “cruising” for parking spots were more destructive than anyone had imagined, and he inspired waves of research into the hidden market values of parking spots, which are rarely bought or sold in their own right. He happily describes himself as an “academic bottom-feeder” who found a wonderful, rich ecological niche down there in the depths.

Shoup has spent decades travelling the world and preaching against the concept of free parking, often meeting with bad-tempered resistance. Nevertheless, he has made a lot of headway in the world of urban planning. Any economist can see immediately how bundling a “free” parking space with an apartment or a job might be inefficient. The renter or homeowner has to pay a hidden extra cost for an amenity he might not choose to use, and the commuter is being given an incentive to drive to work — an incentive whose cash value he might prefer to keep. Shoup soon found, on empirical investigation, that most urban parking lots show signs of less-than-optimum use.

[…]

Of course, too little parking is as much of an efficiency problem as too much, which is why Shoup and his followers want parking to be priced wherever possible: if more is really needed, let a market create it. (To my eyes he has at least as much Hayek in him as Henry George.) In the era of Uber and smartphones, it is a lot easier to imagine a fully Shoupista world in which prices for parking spots update in real time and drivers look up prices at or near their destination before setting out.