ReasonTV

Published 28 Jun 2022The agency will never be controlled by fact-driven experts shielded from politics.

——————-

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was once widely viewed as the gold standard in public health, considered an apolitical, science-driven bulwark against all pathogen threats, foreign and domestic.Today, trust in the agency has plummeted because COVID-19 exposed the truth: The CDC is thoroughly corruptible, and federal regulators will never be impartial experts. They respond to political incentives just like everyone else, and a fact-driven, purely technocratic state is an impossible dream.

The Trump administration pressured the CDC to narrow the scope of testing so case counts would drop, blocked officials from doing interviews, and edited its flagship scientific reports. The CDC provided a scientifically dubious public health rationale for rejecting migrants at the southern border. President Joe Biden continued that policy, and under his purview, CDC guidance on school closures was surreptitiously written by leaders of the country’s second-largest teachers union.

Tom Frieden, a former CDC director, co-authored a 2021 op-ed with three other former agency heads expressing hope that Biden’s incoming CDC Director Rochelle Walensky would “restore the public’s confidence in the CDC’s scientific objectivity,” with its reputation “a shadow of what it once was.” Yet, Frieden endorsed large-scale protests against racial injustice two months after writing in The Washington Post that “the faucet of everyday activities needs to be turned on slowly. We cannot open the floodgates.” Meanwhile, public health officials were keeping people from attending the funerals of their loved ones.

And could it be pure coincidence that the CDC chose the Friday before President Biden’s State of the Union address to drop its indoor mask recommendation for the majority of Americans, even though the supporting data were months old?

In other words, it doesn’t matter who occupies the White House — political incentives mean that, no matter how dedicated or competent the career scientists who work at the CDC are, the agency will never be controlled by fact-driven experts shielded from the “hurry and strife of politics,” as Woodrow Wilson wrote. After decades of mission creep, the CDC’s role should be strictly narrowed, limited to surveillance and coordination, leaving the heavy lifting to local officials and private and academic researchers who are more reactive to direct feedback from their communities.

Written and produced by Justin Monticello. Edited by Isaac Reese. Graphics by Reese, Tomasz Kaye, and Nodehaus. Audio production by Ian Keyser.

Music: “Robotic Butterflies” by Evgeny Bardyuzha; “We Fall” by Stanley Gurvich; “Free Radicals” by Stanley Gurvich.

Photos: BSIP/Newscom; BSIP/Newscom; Sarah Silbiger/UPI/Newscom; Shawn Thew – Pool via CNP/ZUMAPRESS/Newscom; Alex Edelman/ZUMA Press/Newscom; SMG/ZUMA Press/Newscom; Simon Shin/ZUMA Press/Newscom; Michael Brochstein/ZUMAPRESS/Newscom; Adam Schultz/White House/Newscom; Brazil Photo Press / SplashNews/Newscom; Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call/Newscom; Polaris/Newscom; Jonathan Alpeyrie/Polaris/Newscom; Aimee Melo/dpa/picture-alliance/Newscom; Julian Stratenschulte/dpa/picture-alliance/Newscom; Sven Hoppe/dpa/picture-alliance/Newscom; CNP/AdMedia/Newscom

June 29, 2022

COVID Exposed the Truth About the CDC

June 25, 2022

The Public Choice Model in … grand strategy?

One of the readers of Scott Alexander’s Astral Codex Ten has contributed a review of Public Choice Theory and the Illusion of Grand Strategy by Richard Hanania. This is one of perhaps a dozen or so anonymous reviews that Scott publishes every year with the readers voting for the best review and the names of the contributors withheld until after the voting is finished:

[In Public Choice Theory And The Illusion Of Grand Strategy], Richard Hanania details how a public choice model (imported from public choice theory in economics) can explain the United States’ incoherent foreign policy much better than the unitary actor model (imported from rational choice theory in economics) that underlies the illusion of American grand strategy in international relations (IR), in particular the dominant school of realism. As the subtitle “How Generals, Weapons Manufacturers, and Foreign Governments Shape American Foreign Policy” suggests, American foreign policy is driven by special interest groups, which results in millions of deaths for no good reason.

In the unitary actor model, the primary unit of analysis of inter-state relations is the state as a monolithic agent capable of making rational decisions (forming coherent, long-term “grand strategy”) from cost-benefit analysis based on preference ranking and expected “national interest” maximisation.

In the public choice model, small special-interest groups that reap a large proportion of the benefits from a policy (concentrated interests) are much more incentivised to lobby for a policy than the general public who pay for a negligible portion of the cost of the policy (diffused interests) are incentivised to lobby against. The former can coordinate much easier than the latter that has to overcome rational ignorance (the cost of educating oneself about foreign policy outweighs any benefit an one can expect to gain as individual citizens cannot affect foreign policy) and the society-wide collective action problem (irrational for every citizen to cooperate in the prisoner’s dilemma especially if individual gain is negligible) resulting in inefficient (not-public-good-maximising) policymaking i.e. government failure.

And more specifically on the use of Public Choice Theory:

Public choice theory was developed to understand domestic politics, but Hanania argues that public choice is actually even more useful in understanding foreign policy.

First, national defence is “the quintessential public good” in that the taxpayers who pay for “national security” compose a diffuse interest group, while those who profit from it form concentrated interests. This calls into question the assumption that American national security is directly proportional to its military spending (America spends more on defence than most of the rest of the world combined).

Second, the public is ignorant of foreign affairs, so those who control the flow of information have excess influence. Even politicians and bureaucrats are ignorant, for example most(!) counterterrorism officials — the chief of the FBI’s national security branch and a seven-term congressman then serving as the vice chairman of a House intelligence subcommittee, did not know the difference between Sunnis and Shiites. The same favoured interests exert influence at all levels of society, including at the top, for example intelligence agencies are discounted if they contradict what leaders think they know through personal contacts and publicly available material, as was the case in the run-up to the Iraq War.

Third, unlike policy areas like education, it is legitimate for governments to declare certain foreign affairs information to be classified i.e. the public has no right to know. Top officials leaking classified information to the press is normal practice, so they can be extremely selective in manipulating public knowledge.

Fourth, it’s difficult to know who possesses genuine expertise, so foreign policy discourse is prone to capture by special interests. History runs only once — the cause and effect in foreign policy are hard to generalise into measurable forecasts; as demonstrated by Tetlock’s superforecasters, geopolitical experts are worse than informed laymen at predicting world events. Unlike those who have fought the tobacco companies that denied the harms of smoking, or oil companies that denied global warming, the opponents of interventionists may never be able to muster evidence clear enough to win against those in power with special interests backing.

Hanania’s special interest groups are the usual suspects: government contractors (weapons manufacturers [1]), the national security establishment (the Pentagon [2]), and foreign governments [3] (not limited to electoral intervention).

What doesn’t have comparable influence is business interests as argued by IR theorists. Unlike weapons manufacturers, other business interests have to overcome the collective action problem, especially when some businesses benefit from protectionism. By interfering in a foreign state, the US may build a stable capitalist system propitious for multinationals, but can conversely cause a greater degree of instability and make it impossible to do business there; when business interests are unsure what the impact of a foreign policy will be for their bottom line, they should be more likely to focus their lobbying efforts elsewhere.

March 14, 2022

QotD: Crime and (lenient) punishment

A few years ago, an eminent British criminologist said, or admitted, that criminology was a century-old conspiracy to deny that punishment had any effect whatever on criminal behavior.

And certainly, no intellectual ever earned kudos from his peers by arguing that punishment was necessary, let alone that current punishments were too lenient. In general, the more lenient he was in theory, and the more willing to forgive wrongs done to others, the better person he was thought by his peers to be.

In a way, this was understandable. The history of punishment is so sown with sadism and cruelty that it is hardly surprising that decent people don’t want to be associated with it.

Often, horrific punishments were carried out in public, half as deterrence and half as entertainment. Clearly, they failed to result in a law-abiding society, from which it was concluded that what counted in the deterrence of crime was not severity of punishment but the swiftness and certainty of detection.

While the latter are important, however, they are obviously not sufficient. It is not the prospect of detection that causes people to refrain from parking in prohibited places, but that of the fine after detection.

This is so obvious that it would not be worth mentioning, had not so much intellectual effort gone into the denial of the efficacy of punishment as such. Despite this effort, I doubt whether anyone, in his innermost being, has ever really doubted the efficacy of, or necessity for, punishment.

In Britain, leniency has co-existed with a very large prison population. This is not as contradictory as it sounds: for the fact is that something must eventually be done with repeat offenders, who do not take previous leniency as a sign of mercy and an invitation to reform but as a sign of weakness and an invitation to recidivism. Instead of nipping growth in the bud, the British system fertilises the plant.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Our Leniency, and the Necessity of Punishing Crime”, The Iconoclast, 2021-11-29.

January 25, 2022

The fantasy of a modern economy without money

Jon Hersey and Thomas Walker-Werth consider the claim that we’d all be better off without money in a truly modern, egalitarian society:

Capitalism, to the extent it has existed, has been incredibly successful at lifting most of humanity out of poverty, incentivizing the creation of incredible, life-enhancing technologies, such as those Maezawa used to make his fortune — not to mention, travel to space. But it’s long had its critics, and he is far from the first to propose a sort of Garden-of-Eden world where everything is plentiful and free. Karl Marx envisioned a similar utopia. Communism, he said, ultimately would bring about a world without money:

In the case of socialised production the money-capital is eliminated. Society distributes labour-power and means of production to the different branches of production. The producers may, for all it matters, receive paper vouchers entitling them to withdraw from the social supplies of consumer goods a quantity corresponding to their labour-time. These vouchers are not money. They do not circulate.

And although “society distributes labour-power” — meaning government planners tell people what to do to ensure that things (such as “free” Ferraris) get made — workers could also all pursue whatever hobbies or occupations strike their fancy. “[I]n communist society,” Marx explained,

where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, to fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner, just as I have in mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, shepherd or critic.

[…]

Although Marx considered himself a social scientist and economist — and although his ideas are still some of the most widely taught — they aren’t much taught in social science or economics departments, except as foils. That’s because virtually all of Marx’s hypotheses have been debunked. For one, who’s going to build the free Ferraris that Maezawa has dreamed up, never mind tackle more mundane tasks, with no incentive? But for those who don’t find such commonsense thought experiments convincing — or who think, as Marx did, that human nature will somehow mysteriously change — the impracticality of Marx’s moneyless state was demonstrated by what Austrian economists have come to call the calculation problem. Ludwig von Mises once explained the problem as follows:

If a hydroelectric power station is to be built, one must know whether or not this is the most economical way to produce the energy needed. How can he know this if he cannot calculate costs and output?

We may admit that in its initial period a socialist regime could to some extent rely upon the experience of the preceding age of capitalism. But what is to be done later, as conditions change more and more? Of what use could the prices of 1900 be for the director in 1949? And what use can the director in 1980 derive from the knowledge of the prices of 1949?

The paradox of “planning” is that it cannot plan, because of the absence of economic calculation. What is called a planned economy is no economy at all. It is just a system of groping about in the dark.

In short, without prices, people have no relatable, quantifiable means of comparing and contrasting options about how to spend time and capital, which is vital for determining how best to use these naturally scarce resources. “New Scientist magazine reported that in the future, cars could be powered by hazelnuts,” said comedian Jimmy Fallon, in a skit that captures this point hilariously. “That’s encouraging, considering an eight-ounce jar of hazelnuts costs about nine dollars. Yeah, I’ve got an idea for a car that runs on bald eagle heads and Fabergé eggs.”

January 22, 2022

“China’s statistics remain in the hands of officials who carefully do everything possible to make sure China’s image remains unblemished”

I’ve been a disbeliever in official Chinese statistics for many years — one of the first repeat topics on the blog in 2004 was the unreliable nature of Chinese government statistics on economic growth. As a result, I find it very easy to believe that the Chinese statistics on deaths due to the Wuhan Coronavirus pandemic are unreliable, as John Horvat explains:

As the latest wave of COVID cases surges in the West, all is quiet in the East. It has always been quiet. Millions have died from the coronavirus epidemic as it sweeps the world. However, few consider it strange that the nation where the virus first appeared amid an entirely unprotected public of 1.3 billion people should record a mere 4,636 fatalities over the past three years.

China’s statistics remain in the hands of officials who carefully do everything possible to make sure China’s image remains unblemished. They claim that low numbers are due to the communist nation’s brutal “zero tolerance” policies. China is presented as a model for the West.

Some voices are appearing that dispute this claim. One expert says the fatality figures are likely closer to 1.7 million. This figure would put China in the same camp as the rest of the world. It would also point to the failure of the world’s strictest lockdown and explain the recent shutdowns of whole cities and regions due to the virus, which supposedly kills no one in China.

[…]

Communist parties have always used statistics as a tool and weapon to advance their agenda. Officials feel free to change the numbers to reflect well upon the state, which controls everything. Truth is whatever furthers the fortunes of the party. If statistics must be changed as a result, there is no problem. Hence the notorious unreliability of communist statistics.

The problem is complicated by anxious officials who must report good news to party leaders or face the consequences of their failures, including death. Zero tolerance numbers may be statistically impossible and even absurd, but most officials prefer their survival over inconvenient truths.

Also disturbing is the complicity of Western media that repeat the cooked numbers of communist regimes. Few dare to question impossible figures or “follow the science” when leftist prestige is involved. During the long Cold War, the West presented the Soviet Union as the second-largest economy. When the Berlin Wall fell, the actual size of the economy was found to be significantly less.

Even in a centrally planned socialist state, incentives matter. In the west, failing to meet expected standards may get you fired (unless you work for the government), but in authoritarian states like China it can get you shot or exiled to a remote labour camp for years or decades. The top statisticians know that the numbers they work on are … massaged … at every stage even before they are aggregated for regional or national reporting, but there is literally no point in telling the truth and there is much to be gained by “scenario-ing them rosily” because your bosses will only accept good news regardless of reality.

January 21, 2022

Conservatives versus the “Blob”

Sam Ashworth-Hayes is writing here about the British Conservative party, but just swap out the names and it’s equally applicable to the Canadian equivalent, and very likely true for the rest of the western world:

“Palace of Westminster”by michaelhenley is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The Conservative party is trapped in a nightmare of its own making. Number 10 is rocked by scandals, support in the polls is plummeting, the Northern Ireland Protocol (Chekhov’s car bomb) waits patiently for its return to the newscycle. As with every good nightmare, there is the sense of unease that something remains undone.

That something would be “conserving”. Set aside economic policy, where the Conservatives and Labour are still just about separable — although the new interest in higher taxes, spending and regulation is rapidly eroding this gap — and judge the period on the social axis: same-sex marriage, net migration at record highs, the march of progressive ideas through academia, business and press and into government speeches. You could be forgiven for thinking that Labour won the 2010 election, and every bout subsequent.

Why is that the Conservative party governs in such a fundamentally unconservative way? Part of the issue is that the average Conservative MP is, on social issues, basically indistinguishable from the average Labour voter, while the average Labour MP is to the left even of this. The centre of gravity in Parliament is well to the left of the general population.

A second part of the answer — and a partial cause of the first — is that the infrastructure of British politics is not designed for the right. When Michael Gove and his then-Special Advisor Dominic Cummings attempted to shake up the English education system in 2014, they found themselves publicly at war with what they termed “the Blob”: an amorphous conglomerate of civil servants, academics and unions that acted to gum up change and ensure stasis in the interests of its members. Rightwards reform is received as violent revolution, whilst the constant leftwards drift goes unremarked and unchallenged.

When Cummings made his way to Number 10, so did the concept of the Blob, expanded to include the BBC, various quangos, much of Whitehall and what is sometimes called “civil society”. The example of hate crime policy is illustrative of the general idea. The concept is not dissimilar to Curtis Yarvin’s “Cathedral”, or the Trumpian “deep state”. Critics of such accusations point out, not unreasonably, that coordinating so many constituent parts would be almost impossible — but this misses the point entirely. The purpose of a system is what it does, and individual elements responding to an ecosystem of incentives that produce given results can act in a remarkably coordinated way, when those incentives point in the same direction.

November 27, 2021

Americans fear the power of “Big Oil” and other cartels. Canadians rejoice under the buttery thumb of “Big Dairy”

Jen Gerson hates Canada’s supply management “system” with the heat of a thousand suns. And she’s perfectly right to do so:

Former federal Conservative Party leader Andrew Scheer, paid tool of Big Dairy, chugs some milk during a Press Gallery speech in 2017. I’ve called him the “Milk Dud” ever since.

Screencapture from a CTV video uploaded to YouTube.

Many of you readers have listened to the likes of me complain about supply management over the years, but for those of you whose eyes glazed over until you started to notice your rent money disappearing into your grocery bill, here’s a very quick primer.

The supply management system insulates eggs, dairy, and poultry from the vicissitudes of the free market, assuring established farmers in these few sectors a guaranteed return to produce a pre-ordained supply of these products. The federal and provincial governments oversee the system via various dairy commissions.

Some government involvement in dairy has been a feature of our agricultural system since the late 19th century, however the system as it exists today came into effect in the ’70s. It consists, broadly, of three policy mechanisms. Prices are set internally to assure farmers receive a healthy profit for their labour, farmers are protected from competition though ruinous import tariffs, and then supply is managed via a quota system.

As one might expect, this has created extraordinary economic distortions, assuring that a container of milk in Canada is radically more expensive than an identical product south of the border. (Yes, American milk is subsidized too, although less than it once was. And from a consumer’s perspective, so what? If the Americans want to subsidize cheap milk to send north, all the better for shoppers.)

In order to keep production at a steady level, the system has to keep newer, cheaper players from entering the market, and this is accomplished via a quota system that has led to absurd economic incentives and outcomes. According to this report from the Canadian West Foundation from 2016, the quota was valued at about $28,000 per cow. That means that the value of the right to own one milk-producing cow far outweighed the actual value of the animal — and someone seeking to start a dairy farm would need to pay for millions of dollars worth of quota in addition to cows, land, food, and farm equipment.

The quotas themselves are a multi-billion dollar racket; this is roughly akin to the way a license to run a taxi costs hundreds of thousands of dollars in some cities, many multiples of the value of the car itself. When a government creates a regulatory system that imposes artificial scarcity, the value of the thing regulated radically increases.

Since the supply management system was introduced, much of the agriculture has consolidated; this, combined with the value of the quotas they possess mean that most dairy farms — far from being quaint, picturesque family homesteads — are multi-million dollar operations, with farmers themselves making six-figure profits after paying their own wages.

The system has also proved a obstacle in multiple free-trade deals, arguably making it difficult for other agriculture sectors to compete globally.

And who pays for all of this?

Well, of course, you do.

November 7, 2021

QotD: Shoe manufacturing in the Soviet Union

The Commies weren’t big on consumer goods for obvious reasons, but even the proles need shoes. If you’re a Communist (or a teenager), it seems simple enough: send your flunkies out into a region, have them write down everyone’s shoe sizes, and then make those. Which would work, I guess, if not for the fact that industry doesn’t operate that way. Industries are only efficient through economies of scale. “A shoe factory” only beats “a cordwainer” because the factory can crank out 10,000 pairs of shoes in the time it takes the cordwainer to produce one pair. Worse, factories are massive resource sinks if they’re not running at full blast at all times …

After trying several workarounds, GOSPLAN, the state production ministry, decided to use “Gross Output Targets” to produce goods. Which probably worked ok for stuff like rebar, if you don’t care about quality (see Mao’s DIY backyard blast furnaces), but is terrible for stuff like shoes. So let’s say GOSPLAN decides that 100,000 lucky proles of Irkutsk Oblast shall receive one pair of shoes apiece. Since all materials had to be requisitioned in advance from GOSSNAB (I confess: I love Soviet acronyms), and since the production line would need to be re-tooled for each individual size and style of shoe, the factory managers — who had to hit the Gross Output Target, or go tour Siberia — did the only logical thing: They cranked out 100,000 baby shoes, all left feet. (Baby shoes use less leather; the excess can be sold or traded, see below).

Again, Commies couldn’t care less about consumer complaints, but eventually some up and comer in the Party will notice that everyone is wandering barefoot around a big pile of baby shoes. That might make him look bad, so he sends a report, and, after a long and convoluted bureaucratic process, GOSPLAN revises their order: 100,000 pairs of shoes, but in different sizes and styles, for men and women. In response to which, the factory manager does the only logical thing: 99,999 pairs of baby shoes, all left feet, plus one pump and one wingtip.

Lather, rinse, repeat. The factory manager isn’t a bad guy — in fact, let’s say he’s Wyatt. He’s just operating on an entirely different incentive structure than even his immediate boss, to say nothing of the faceless apparatchiks at GOSPLAN. Hitting any Gross Output Target is a real task, given that his workforce is a bunch of illiterate peasants who hate him and are constantly drunk. What probably seems like spectacularly inventive cruelty to the proles of Irkutsk Oblast is just Wyatt doing everything he can to keep his family out of the Gulag. And since Wyatt’s a smart guy, he can get around any target GOSPLAN sets. If they tell him to produce 100,000 pounds of shoes, his factory cranks out one enormous pair of concrete sneakers.

That’s one of Wyatt’s two overriding priorities: Staying out of the Gulag. The other one is: Using whatever he can scrimp, save, or scrounge from GOSSNAB as trade goods in the black market.

Here again, Wyatt’s not a bad guy. He’s not doing this to feather his own nest (though of course he lives a little better than others; he’s only human). In the words of the immortal Mike Tyson, everyone has a plan until he gets punched in the mouth, and even the most meticulously “scientific” management gets punched in the mouth all the time. As we’ve seen, GOSPLAN can’t even get it right with something as low-tech, as easy to mass-produce as shoes, so imagine how they do with more complex bits of equipment. The factory managers, who have to hit the Gross Output Targets, no matter what, quickly figure out that they’ll be waiting until doomsday if they try requisitioning what they need from GOSSNAB, so they form a kind of black market between themselves. Indeed there’s an entire class of quasi-criminals, whose name I forget, that exists only to facilitate such transactions.

Extend that paradigm to everything, and you’ve got life in the USSR. There’s the “official” economy, which is pure fantasy. There’s the black market economy at the factory level, where bulk materials change hands (since the official economy is pure fantasy, nobody blinks an eye when, say, 100,000 metric tons of concrete disappears off a manifest somewhere and reappears, un-manifested (as it were), somewhere else). There’s the black market at the consumer level, since of course the poor proles of Irkutsk Oblast have to have shoes and there’s no way they’re getting them from Wyatt’s factory. And finally, there’s the black market at the service level — those go-betweens arranging for 100,000 metric tons of concrete to fall off a truck in Vladivostok and appear, like magic, in Kiev (and their consumer-level equivalents — think pimps, but for everything).

Severian, “Darker Shade of Black IV: Black Market”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-04-02.

September 25, 2021

Will Mars become the equivalent to Earth that India and the East Indies once were for Europe?

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes goes a long way in both time and space away from his normal Industrial Revolution beat to consider what might happen as humans attempt to colonize Mars:

The first true-colour image generated using the OSIRIS orange (red), green and blue colour filters. The image was acquired on 24 February 2007 at 19:28 CET from a distance of about 240 000 km; image resolution is about 5 km/pixel.

Photo taken by the ESA Rosetta spacecraft during a planetary flyby.

The other week I attended an unconference, which had a session on the implications of establishing colonies on other planets. Although this was largely meant to be about the likely impact on Earth’s natural environment — what will be the impact of extracting raw materials from asteroids and other planets? — some of the discussion reminded me of the challenges faced by the long-distance explorers, merchants, and colonists of four hundred years ago. There are quite a few parallels I can see between travelling to Mars, say, in a hundred years’ time, and travelling between continents in the age of sail.

For a start, there’s the seasonality and duration of the voyages. European ships headed for the Indian Ocean had to time their voyages around the monsoon season; trips across the Atlantic were limited to just half the year because of hurricanes. Round-trips took years. Similarly, the departure window for a voyage from Earth to Mars only comes around once every 26 months, and even the most optimistic estimates place eventual journey times at about 4-6 months. Supposing that Mars can be permanently settled, any colony there will likely be extremely dependent on the regular arrival of resupply craft. There’s only so long that any group can survive in a hostile environment on their own.

[…]

The Portuguese had once been the only Europeans to trade directly into the Indian Ocean, but the structure of their trade — essentially a state-run monopoly with some licensed private merchants — was unable to compete with the arrival of the Dutch. The initial Dutch forays into the Indian Ocean in the 1590s had originally been financed by lots of different companies, often associated with particular cities — similar to the proliferation of billionaire-led space exploration companies today. But the Dutch soon recognised that such a high-risk trade would only be able to survive if it came with correspondingly high rewards — rewards that could only be guaranteed by eliminating domestic competitors (and if possible, foreign ones too). They therefore amalgamated all of the smaller concerns into a single company with a state-granted monopoly on all of the nation’s trade with the region. In this, they actually copied the English model, but then outdid them in terms of the organisation and financing of that company […].

Are we likely to see a similar move towards state-granted monopoly corporations when it comes to space colonisation? I suspect it depends on the potential rewards, and on the strength of the competition. There is certainly precedent for incentivising risky and innovative ventures in this way, through the granting of patent monopolies. Patents for inventions in the English tradition originally even had their roots in patents for exploration. I would not be surprised if such policies end up being used again by countries that are late-comers to the space race, perhaps by granting domestic monopolies over the extraction of resources from particular planets or moons. Although direct state funding can help in being first, like they did for Spain and Portugal in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, state-granted monopolies for private actors may again end up being the ideal catch-up tool for laggards, as they were for the English and the Dutch.

How the monopolies are managed will also matter. The English East India Company, for example, was initially more focused on rewarding its shareholders than it was on investing in the full infrastructure with which to dominate a trade route. The Dutch company, by contrast, from the get-go was part of a more coordinated imperial strategy — one that sought to systematically rob the Portuguese of their factories and forts, to project force with the aid of the state. Indeed, if there’s one big lesson for the geopolitics of space, it’s that far-flung empires can be extremely fragile, with plenty of opportunities for late-arriving interlopers to take them over.

Although it’s difficult to imagine space colonies being able to become self-sufficient any time soon, it seems likely that those controlled by particular companies or countries may occasionally be persuaded — by bribes or by force — to defect. What’s to stop them when they’re hundreds of millions of kilometres away from any punishment or help? Ill-provisioned factors, forts, or colonies happily switched sides to whoever might provision them better. As I mentioned last week, such problems curtailed the ambitions of other would-be colonial powers, like the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. When the Dutch turned up in the Indian Ocean, many of the Portuguese forts they threatened simply surrendered.

I bow to Anton’s far greater historical knowledge in most things, but state monopolies in the 16th to 19th centuries were very different creatures than their potential modern equivalents, and the much more comprehensive degree of state control of the economy now would probably mean that a state monopoly over extraterrestrial activities would be a worst-possible outcome. The greater the powers in the hands of the state, in almost every case, the worse all state-controlled activities have become. The incentives of civil servants are vastly different than those of individuals or businesses and are farcically incompatible with the risk-taking necessary on a dangerous frontier.

September 10, 2021

Why even highly gifted young quarterbacks rarely succeed as they move toward the NFL

Severian at Rotten Chestnuts looks at the early career life-cycle of football quarterbacks:

At all levels of American football below pro, the “option” is a major facet of the game. This is an offensive play where the quarterback can either run the ball himself, pitch it to another player, or throw it downfield, as he thinks best. It certainly helps if the quarterback is a strong-armed, accurate passer, but the key criterion here is speed. If you get defenders cheating up in order to stop the run, you don’t have to be as strong or accurate with your throws. What matters is that the QB can pass — meaning, he can throw it X yards downfield, within a few yards’ radius of a given spot — not how often he does so. The closer he can get it to the spot, and the further downfield that spot is, the better, but so long as he’s in the vicinity the option system works well.

This starts very, very early in a player’s career. The lower down the skill ladder you go, the more prominent the “option” offense. In “Pop Warner” leagues — kids below age 12, basically — the option pretty much IS the offense, since few kids can throw the ball very far, much less with accuracy. Throwing a football with both velocity and accuracy is extremely difficult, and it doesn’t help that sound throwing mechanics feel brutally unnatural — you know you’re doing it right when it feels like your shoulder is going to pop out of its socket at the very instant your elbow ligaments snap and hit you in the face … which, unfortunately, is exactly what it feels like when you’re doing it wrong, and your shoulder IS about to pop out at the same moment your elbow ligaments snap.

What happens, then, is that kids generally learn how to throw with very poor form … but coaches generally aren’t going to correct them, either because they don’t know the proper mechanics themselves, or because they are focused exclusively on winning games. Who cares if little Kayden, Brayden, or Jayden is going to blow his arm out hucking it like that when he hits high school? That’s Coach Smith’s problem. All that matters now is that he can get it to X spot with radius Y.

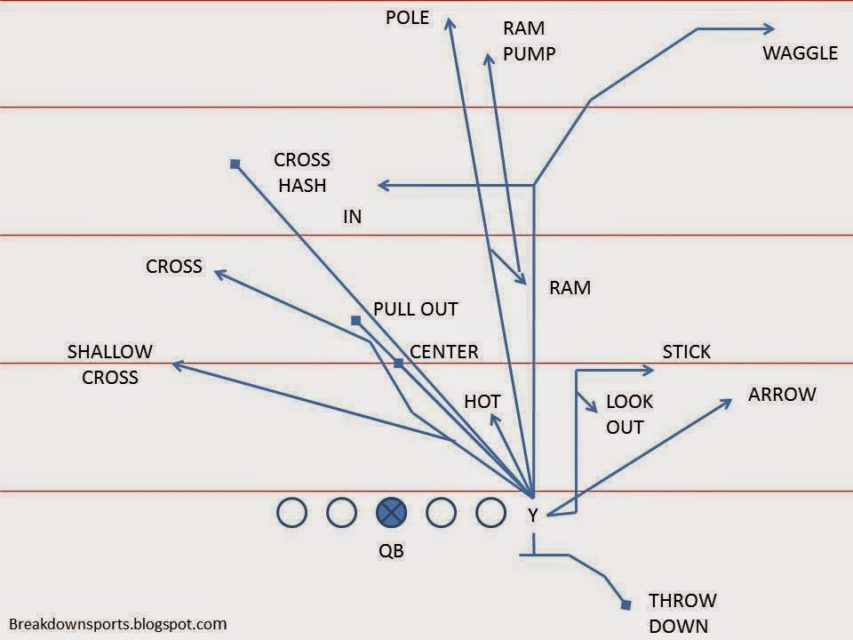

Thus the possible career path of any kid who can throw a football reasonably well quickly diverges. If he’s too slow to run the option effectively, his coaches will try to turn him into an “air raid” style quarterback, which means he throws on every play, mechanics be damned, because we need to win now, and what the hell, he can get it there, can’t he? But even the “air raid” style of play is enormously more difficult to coach, because that means you need to be able to coach a whole corps of wide receivers to run a whole bunch of increasingly complex routes. Here, look:

That’s what’s known as a “route tree”, and all of your receivers — five guys, usually, on every play, plus their backups — need to know how to run every one of them, every time. Which means your playbook is going to be huge, because you (theoretically, anyway) need a play for each one of those routes, for each receiver on the field. And obviously your quarterback has to have something going on upstairs, because he needs to memorize five different guys’ routes for every single play, plus audibles and checkdowns (changing any given player’s route, or even the entire play, on the fly), and so on.

I’m sure y’all see where I’m going with this, but it’s important to note that the key selection — whether a given kid shall be an “option” quarterback, or an “air raid” quarterback — has been made by someone else, much lower on the skill ladder. It would be great if one and the same kid could do both to a high degree of skill, but since human neurons apparently don’t work like that, it’s natural for everyone involved to take the path of least resistance.

And again, I’m not blaming coaches for this. Forget things like “getting fired for losing too many games”, and just consider the sheer amount of work. Stipulating for the sake of argument that you’ve got 50 man-hours in a week to get ready for a game, how do you best allocate them? Getting your QB to throw with proper mechanics alone probably takes a significant chunk of that time, and even though he’ll have to do a lot of it on his own — throwing passes at a tire in the backyard until his arm feels ready to fall off — you’re still spending a LOT of time on something that will make no appreciable difference to the game’s outcome this Friday night. And then throw in the other stuff — how much time does it take just to “install” (as the term d’art is) a game plan that has all those routes in it, much less coaching all the receivers up to where they can run them all?

Nah, brah. Just hand Jonquarious the ball and let him run it, and if he has to huck it downfield every now and again, let him do it his way. Again, this will make no difference at all to the outcome of this week’s game — he’ll either run it or he won’t; make the throw or not — but it frees up a lot of man hours to do all the other stuff a coach has to do that we haven’t talked about yet, such as defense.

July 30, 2021

The British government reaches deep into the bag of “nudge” tricks yet again

Britain’s public health boffins have got the government agitated enough to try major incentives to encourage British shoppers to buy healthier, lower-calorie foods. Tim Worstall explains that, because those shoppers are human beings, this suite of incentives won’t do at all what Nanny expects them to do:

Now consider how it has to work. You go shopping, you present your DimbleCard and gain points for the healthiness of that shopping basket. Lettuce and carrots galore, super, free ticket to London on the choo choo.

So, where are the chocco biccies? If you buy them when presenting your card then no choo choo for you. What happens?

The lettuce and the carrots are bought on the card, the chocco biccies are not. Everyone simply does two transactions, with DimbleCard and sans. Lots of free choo choo and no change, whatsoever, in diet.

Yes, of course people will do this. For that’s what people do. Survey the landscape of incentives in front of them then maximise their utility, the outcome, in the face of them. It’s a restricted rationality, restricted by knowledge, but it is there. Everyone will fiddle the system because that’s what it is to be human. Collecting the fire from the lightning strike is fiddling the universe, that’s just what we do.

This being why so many clever schemes to encourage or deter this or that just don’t work. This being why those detailed plans for men, if not mice, gang aft into idiocy. Because we out here, hom sap, will play whatever system there is to our benefit.

No, this will not work out like supermarket loyalty cards. Yes, it’s true, most of us do use them. But the incentive is for us to do so. The more we do use them then the more discounts we gain, the better off we are, even at the cost of that data. How does this new government one work? The less we buy of certain things the better off we are. So, less of those things will be bought using the cards.

It is not possible to insist that people must use the card to buy things. Well, not unless we’re about to descend into the dystopia desired by Caroline Lucas it’s not. There might be a card reader at the point of purchase but the supermarkets will not demand that a sale can only happen when a card is read.

Therefore there will be those sales which gain points which make prizes. There will also be those DimbleCardless sales which do not gain points, or even demerits, and are done without their being registered in the system.

June 17, 2021

Encouraging innovation by … rejigging the honours system

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers how one man’s efforts to encourage and reward innovation in the United Kingdom eventually led to “mere inventors” receiving honours that once were dedicated to military paladins and political giants:

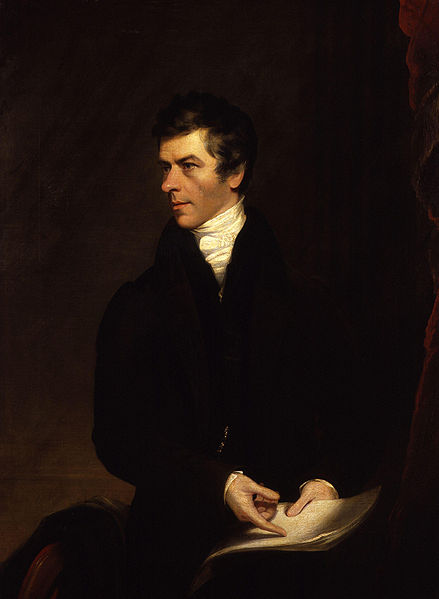

Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux, by James Lonsdale (died 1839), given to the National Portrait Gallery, London in 1873.

Image from the National Portrait Gallery via Wikimedia Commons.

One of my all-time favourite innovation evangelists is the nineteenth-century barrister, journalist, and politician Henry Brougham. He was an innovator himself, in the late 1830s designing a form of horse-drawn carriage, and as a teenager even managed to get his experiments on light published in the Royal Society’s prestigious Transactions. But his main achievements were as an organiser. Clever, dashing, and articulate, the son of minor gentry, he was an evangelist extraordinaire. In the 1820s he helped George Birkbeck to found the London Mechanics’ Institute (which survives today as Birkbeck, University of London), was instrumental in the creation of University College London (to provide a university in England where you didn’t have to swear an oath to the Church of England), and founded the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (to print reference works and textbooks cheaply and in bulk). They were all organisations intended to widen access to education, spreading science to the masses.

He also presided at the opening of many more worker-run mechanics’ institutions, libraries, and scientific societies. As a Member of Parliament who went out of his way to support workers’ efforts at self-education, even though none of them could vote, Brougham thus became something of a celebrity to working-class inventors. John Condie, born in Gorbals, Glasgow, to poor parents, and apprenticed to a cabinet maker, would become a prolific and successful improver of iron-making, locomotive springs, and photography, as well as an inspiring lecturer on scientific subjects in his own right — his students at the Eaglesham Mechanics’ Institution were reportedly so engrossed that they would attend his evening classes until midnight. Having once exhibited a model steam engine at the opening of the Carlisle Mechanics’ Institution, however, Condie was reportedly “not a little proud” that Brougham — who had presided at the opening — recalled the model over thirty years later. The detail comes from Condie’s obituary notice in the local papers; I like to think that it was a story upon which he frequently dined out.

Brougham’s celebrity, I suspect, made him appreciate the usefulness of status and prestige, and his influence only grew when in 1830 he was made a lord and appointed Lord High Chancellor — a high-ranking ministerial position, which he held for four years. Brougham was soon behind many efforts to increase the visibility of inventive role-models. The nineteenth-century mania for putting up statues — to people like Johannes Gutenberg, Isaac Newton, and James Watt — often had Brougham or his political allies behind them. Brougham even hoped that while the “temples of the pagans had been adorned by statues of warriors, who had dealt desolation … ours shall be graced with the statues of those who have contributed to the triumph of humanity and science”.

His hero-making extended to print, too, when in the 1840s his Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge embarked on publishing a comprehensive biographical dictionary — an early forerunner to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, but with the extraordinary aim of covering notable individuals from all over the world. It managed to print seven volumes covering the letter “A” before financial considerations forced the whole society to cease, but in 1845 Brougham published Lives of Men of Letters and Science who Flourished in the Time of George III, in which he showcased a handful of eighteenth-century literati and scientists from whom readers were to draw inspiration.

And Brougham tried to raise the status of inventors who were still living. This was done by co-opting a Hanoverian order of chivalry, the Royal Guelphic Order (by this stage the kings of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland were also simultaneously the kings of Hanover). The order was generally used to recognise soldiers, but an interesting precedent had been set when the astronomer Frederick William Herschel, the discoverer of Uranus, had been made a knight of the order in 1816. So when Brougham rose to power in the 1830s, he envisaged using it more widely, to recognise inventors, scientists, and medical pioneers, as well as literary scholars like museum curators, archivists, antiquarians, historians, heralds, and linguists. Thanks to Brougham’s machinations, the knighthood of the order was offered to the mathematician James Ivory, the scientist and inventor David Brewster, and the neurologist Charles Bell (after whom Bell’s Palsy is named). It was later also awarded to serial inventors like John Robison, who improved the accuracy of metal screws, experimented with cast iron canal locks and the water resistance of boats, and applied pneumatic presses to cheesemaking.

One problem, however, was that the Royal Guelphic Order was considered second-rate. It was technically a foreign order, and did not actually entitle one to be called “Sir” in the UK. The mathematician and computing pioneer Charles Babbage was apparently insulted to have been fobbed off with the offer of a Guelphic knighthood instead of a British one. Although William Herschel had accidentally been called “Sir” during his lifetime, this was soon realised to be a mistake in protocol. When his son John — a scientific pioneer in his own right — was also made a knight of the order, he was also quietly knighted normally a few days later so that the rest of the family would be none the wiser. And regardless, the whole scheme came to an end with the accession of Queen Victoria in 1837 — as a woman, she did not inherit the throne of Hanover, and so appointments to the Guelphic order simply passed out of British control.

March 6, 2021

QotD: Why “the rich” benefit more from tax cuts

It might be worth our giving a little explanation to The Guardian about how tax systems work. We impose taxes upon certain things. Activities, transactions, even at times unsuccessfully upon mere existence as with the poll tax. These taxes are then paid by those who indulge in such activities, perform such transactions, have the temerity to exist. If we then decide to cut the tax rate or level on an activity, type of transaction or mode of existence then it will be those who formerly paid the tax on such who benefit from the tax cut on such. This shouldn’t be all that difficult for people to understand but we do seem to have an entire newspaper devoted to not grasping the point […]

There is that objectionable idea that not taxing something is a giveaway. The root presumption there is that everything belongs to the State and we’re lucky it allows us to keep anything to deploy as we desire and not as those who stay awake in committee do. This is not an assumption that leads to a free country nor populace, nor a liberal society.

But it’s also to miss that logical point, that if income tax is to be reduced then it must be those currently paying income tax who benefit from not doing so in the future under the new rates. […] The low paid cough up hardly anything in income tax. Therefore the low paid gain hardly anything from income tax being reduced. This should be obvious.

Tim Worstall, “Budget Revelation – Those Who Pay Income Tax Benefit From Income Tax Cuts”, Continental Telegraph, 2018-10-30.

February 8, 2021

The quality of medical information available to journalists

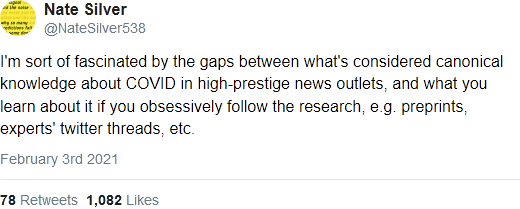

Scott Alexander shows the conflicting agendas of journalists and the medical professionals they depend on for their background information in writing about medical issues:

I heard from a journalist yesterday after writing yesterday’s post on WebMD. They’ve been trying to write a coronavirus article worthy of Zvi or any of the other illegibly smart people writing on the pandemic. Apparently the bottleneck is sources.

In most journalistic settings, you can’t just write “here’s what I think”. You have to write “here’s what my source, a recognized expert, said when I interviewed them”. And the experts are pretty sparing with their interviews for contrarian stories.

The way my correspondent described it: sources don’t usually get to approve the way they’re quoted in an article, or to see it before it gets published. So they’re really cagey about saying anything that might get misinterpreted. Maybe their real opinion is that X is a hard question, there are good points on both sides, but overall they think it probably isn’t true. But if a reporter wants to write “X Is Dumb And All Epidemiologists Are Idiots For Believing It”, they can slice and dice your interview until your cautiously-skeptical-of-X statement sounds like you’re backing them up. So experts end up paranoid about saying potentially-controversial-sounding things to reporters. And since reporters can’t write without sources, it’s hard for them to write anything controversial about epidemiology.

The incentives for the journalist and their editor is to find a sensational angle to get as many people to read the piece as possible (“clickbait” works). The incentives for the “expert sources” are to avoid saying anything substantive that might provide such an angle (“don’t become a headline”). It’s no wonder that journalists with no specialized training in the experts’ area are unable to produce fully informative articles for public consumption.

February 6, 2021

“WebMD is the Internet’s most important source of medical information. It’s also surprisingly useless”

Scott Alexander discusses why WebMD is not the be-all and end-all of internet medical resources:

WebMD is the Internet’s most important source of medical information. It’s also surprisingly useless. Its most famous problem is that whatever your symptoms, it’ll tell you that you have cancer. But the closer you look, the more problems you notice. Consider drug side effects. Here’s WebMD’s list of side effects for a certain drug, let’s call it Drug 1:

Upset stomach and heartburn may occur. If either of these effects persist or worsen, tell your doctor or pharmacist promptly. If your doctor has directed you to use this medication, remember that he or she has judged that the benefit to you is greater than the risk of side effects. Many people using this medication do not have serious side effects. Tell your doctor right away if you have any serious side effects, including: easy bruising/bleeding, difficulty hearing, ringing in the ears, signs of kidney problems (such as change in the amount of urine), persistent or severe nausea/vomiting, unexplained tiredness, dizziness, dark urine, yellowing eyes/skin. This drug may rarely cause serious bleeding from the stomach/intestine or other areas of the body. If you notice any of the following very serious side effects, get medical help right away: black/tarry stools, persistent or severe stomach/abdominal pain, vomit that looks like coffee grounds, trouble speaking, weakness on one side of the body, sudden vision changes or severe headache.

And here’s their list of side effects for let’s call it Drug 2:

Nausea, loss of appetite, or stomach/abdominal pain may occur. If any of these effects persist or worsen, tell your doctor or pharmacist promptly. Remember that your doctor has prescribed this medication because he or she has judged that the benefit to you is greater than the risk of side effects. Many people using this medication do not have serious side effects. This medication can cause serious bleeding if it affects your blood clotting proteins too much. Even if your doctor stops your medication, this risk of bleeding can continue for up to a week. Tell your doctor right away if you have any signs of serious bleeding, including: unusual pain/swelling/discomfort, unusual/easy bruising, prolonged bleeding from cuts or gums, persistent/frequent nosebleeds, unusually heavy/prolonged menstrual flow, pink/dark urine, coughing up blood, vomit that is bloody or looks like coffee grounds, severe headache, dizziness/fainting, unusual or persistent tiredness/weakness, bloody/black/tarry stools, chest pain, shortness of breath, difficulty swallowing.

Drug 1 is aspirin. Drug 2 is warfarin, which causes 40,000 ER visits a year and is widely considered one of the most dangerous drugs in common use. I challenge anyone to figure out, using WebMD’s side effects list alone, that warfarin is more dangerous than aspirin. I think this is because if WebMD said “aspirin is pretty safe and most people don’t need to worry about it”, people might use aspirin irresponsibly, die, and then their ghosts might sue WebMD. Or if WebMD said “warfarin can be dangerous, be careful with this one”, people might refuse to take warfarin because “the Internet said it was dangerous”, die of the stuff warfarin is supposed to treat, and then their ghosts might sue WebMD. WebMD solves this by never giving the tiniest shred of useful information to anybody.

This is actually a widespread problem in medicine. The worst offender is the FDA, which tends to list every problem anyone had while on a drug as a potential drug side effect, even if it obviously isn’t. This got some press lately when Moderna had to disclose to the FDA that one of the coronavirus vaccine patients got struck by lightning; after a review, this was declared probably unrelated. For the more serious version of this, read Get Ready For False Side Effects. Why does the FDA keep doing this if they know it makes their label information useless? My guess is it’s because they don’t want to look like cowboys who unprincipledly consider some things but not other things. What if someone accused the person deciding what things to consider of being biased? So the FDA comes up with a Procedure, and once you have a Procedure it has to be “take everything seriously”, and then it falls on random small-fry people who aren’t the FDA to pick up the slack and explain which side effects are worth worrying about or not, and then those small fries don’t do that, because they could get sued.

I think the same concern motivates WebMD diagnosing everything as cancer. If they said something other than cancer, then people might sigh with relief, not bother to get a cancer screening, die from some weird cancer that doesn’t present the way normal cancers do, and then their ghosts might sue WebMD.

Of course, WebMD and other online medical information sites didn’t invent hypochondria, they merely made it easier to do to yourself what Jerome K. Jerome did one fine London morning in 1888:

I remember going to the British Museum one day to read up the treatment for some slight ailment of which I had a touch — hay fever, I fancy it was. I got down the book, and read all I came to read; and then, in an unthinking moment, I idly turned the leaves, and began to indolently study diseases, generally. I forget which was the first distemper I plunged into — some fearful, devastating scourge, I know — and, before I had glanced half down the list of “premonitory symptoms,” it was borne in upon me that I had fairly got it.

I sat for awhile, frozen with horror; and then, in the listlessness of despair, I again turned over the pages. I came to typhoid fever — read the symptoms — discovered that I had typhoid fever, must have had it for months without knowing it — wondered what else I had got; turned up St. Vitus’s Dance — found, as I expected, that I had that too, — began to get interested in my case, and determined to sift it to the bottom, and so started alphabetically — read up ague, and learnt that I was sickening for it, and that the acute stage would commence in about another fortnight. Bright’s disease, I was relieved to find, I had only in a modified form, and, so far as that was concerned, I might live for years. Cholera I had, with severe complications; and diphtheria I seemed to have been born with. I plodded conscientiously through the twenty-six letters, and the only malady I could conclude I had not got was housemaid’s knee. […] I had walked into that reading-room a happy, healthy man. I crawled out a decrepit wreck.