Practical Engineering

Published 1 Oct 2024Sand: a treatise …

There’s a lot changing in the construction industry, and a lot of growth in the need for materials like sand and gravel. But I don’t think it’s fair to say the world is running out of those materials. We’re just more aware of all the costs involved in procuring them, and hopefully taking more account for how they affect our future and the environment.

(more…)

January 18, 2025

Is the World Really Running Out of Sand?

July 23, 2024

Claim – “Everybody wants Gaza’s gas”

Tim Worstall explains why the popular idea that it’s demand for the natural gas reserves that sit under Palestine that is driving much of the situation in the Middle East is utter codswallop:

“Oil Platform in the Santa Barbara Channel, California” by Ken Lund is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 .

So we’ve a big thing about how all this fighting in Gaza is really about fossil fuels. @JamesMelville seems to think it’s true:

“Everybody wants Gaza’s gas.”

Oil and gas reserves – that’s the real proxy war in the Middle East.

This video provides a really succinct summary of the situation.

This “really succinct” summary includes the idea that the invasion of Iraq was all about access to that country’s oil. Which is very silly indeed. Before the war people paid Iraq for the oil. During the war people paid Iraq for the oil. After the war people are paying Iraq for the oil. The war hasn’t changed Iraq’s oil price — the global oil price has changed it, but not the war — and so the effect of the war upon access to Iraq’s oil has been, well, it’s been zero.

No, it’s not possible to then go off and say that Iraq wouldn’t sell to Americans and that’s why or anything like that. The US didn’t buy much Middle East oil anyway — mainly West African instead. But more than that, this is idiocy about how commodity markets work.

This is something we can test with a more recent example. So, there are sanctions on Russian oil these days over Ukraine. Western Europe, the US, doesn’t buy Russian oil. Russia is still exporting about what it used to. Because it’s a commodity, oil is.

What’s happening is that the Russian oil that used to come to Europe now goes to — say — India. And the Far East, or Middle East, whatever, oil that used to go to India now comes to Europe (the US is now a net exporter itself). Because that’s what happens with commodities. The very name, commodity, means they are substitutable. So, if one particular source cannot sell to one particular user then there’s a bit of a reshuffle. The same oil gets produced, the same oil gets consumed, it’s just the consumption has been moved around a bit and is now by different people. The net effect of sanctions on Russian oil has been, more or less, to increase the profits of those who run oil tankers. Ho Hum.

We’re also treated to the revelation that the US wants everyone to use liquefied natural gas because the US is the big exporter of LNG (well, it’s one). Therefore the US insists that Israel must develop the LNG fields off Gaza. Which is insane. If you’re an exporter you don’t want to start insisting on the start up of your own competition. The US demanding that the LNG not be produced at all would make logical sense but that’s not how conspirazoid ignorance works, is it? It has to be both a conspiracy and also a ludicrous one.

And a third claim. That this natural gas off Gaza is really worth $500 billion. That’s half a trillion dollars. We’ve looked at this value of gas off Gaza claim before and it’s tittery. $4 billion (that’s four billion, not five hundred billion) might be a reasonable claim and that’s just not enough to go to war over.

May 9, 2024

“The ability to believe entire gargling nonsense is strong in the [environmental] sector – as with this particular claim that we’re going to run out of rock”

Tim Worstall really, really enjoys kicking the stuffing out of strawman arguments, especially when they touch on something he’s very well informed about:

Some environmental claims are not just perfectly valid they’re essential for the continuation of life at any level above E. Coli. None of us would want the Thames to return to the state of 1950 when there was nothing living in it other than a collection of that E. Coli reflecting the interesting genetic and origin mix of the population of London. Sure, the arguments from Feargal and the like that a river running through 8 million people must be clean enough to swim in at all times is a bit extreme the other way around. One recent estimate has it that to perform that task for England would cost £260 billion — a few swimming baths sounds like a more sensible use of resources than getting all the rivers sparkling all the time.

Some are more arguable — violent and immediate climate change would be a bad idea, losing Lowestoft below the waves (possibly Dartford too) in 2500 AD might be something we can all live with. Arguable perhaps.

But some of these claims are wholly and entirely doolally. So much so that it’s difficult to imagine that grown adults take them seriously. But, sadly, they do and they do so on our money too.

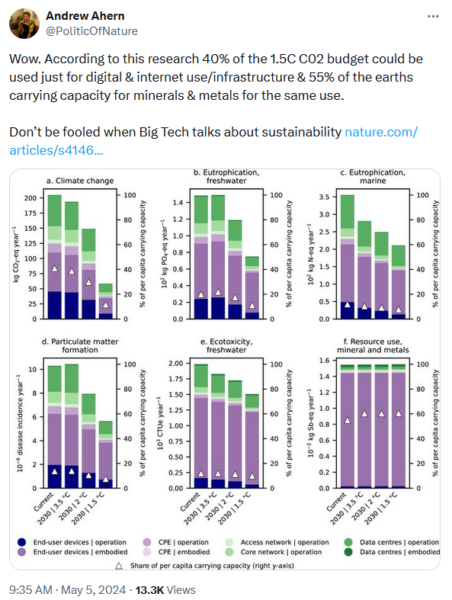

Wow. According to this research 40% of the 1.5C C02 budget could be used just for digital & internet use/infrastructure & 55% of the earths carrying capacity for minerals & metals for the same use.

The internet alone could use 55% of the Earth’s carrying capacity of metals and minerals? Well, to take that seriously is insane. That is not mere hyperbolic insult, that actually is insane. I write as someone who has written an entire book on this very subject (available here, for free, save your money to buy a subscription to this excellent Substack instead). There is no metal or mineral that we’re even going to run short of — in the technical, not economic, sense that is — for tens of millions of years yet. As the average lifetime of a species is perhaps 2 million years that should see us out.

So, clearly, they’re using some odd definition of how many minerals and metals we’ve got that we can use. I thought they’d do the usual Club of Rome thing (no, read the book to find out), confuse mineral reserves with what’s available and thus insist we all died last Tuesday afternoon. Rather to my surprise, no, they didn’t. They went further into raging lunacy.

It’s not wholly obvious as they don’t really quite announce their assumption, it’s necessary to track back a bit — and that’s a problem in itself. A top tip about scientific papers — if they say “As Bloggs said” then what that really means is that many people accept what Bloggs said as being true and also useful. You do not have to reprove Einstein every time you do physics, you can just say “As is known”. You’ve only got to reprove Al if that’s what you’re really trying to do.

Thus, if a definition is a referral back to something else, elsewhere, then you can be sure that the definition is a building block being used by others in their own papers. It’s a generalised insanity, not a specific one.

So, what is that limit?

Here we quantify the environmental impacts of digital content consumption encompassing all the necessary infrastructure linked to the consumption patterns of an average user. By applying the standardised life cycle assessment (LCA) methodology, we evaluate these impacts in relation to the per capita share of the Earth’s carrying capacity using 16 indicators related to climate change, nutrients flows, air pollution, toxicity, and resources use, for which explicit thresholds that should never be exceeded were defined

Now this is in Nature Communications. So it’s science. Even, it’s Science. It’s also lunatic. For, tracking back to try to find what those “resources use” are that will be 55% used up by the internet. It’s possible to think that maybe we’re going to use too much germanium in the glass in the fibreoptic cables say, or erbium in the repeaters, or … specific elements might be in short supply? As the book wot I wrote above points out, that’s nonsense. So, what is the claim?

Tracking back we get to this:

Resource use, mineral and metals MRD kg Sb eq Abiotic resource depletion (ADP ultimate reserves) 2.19E+08 3.18E-02 JRC calculation based on factor 2 concept Bringezu (2015); Buczko et al. (2016) Resource use

That’s from Table 3.

Which takes us one stage further back. This paper here is talking about Planetary Boundaries and as with the building block idea. PBs — I assume — make the assumption that Bringzeu, and Biczlo et al have given us a useful guide to what those PBs are. Which is why they just use their method, not invent a new one. But that, in turn, also means that other people working on PBs are likely to be using that same definition.

[…]

Note what they’re doing. Humans should not take out of that environment more than nature puts back into it each year. That’s some pretty dumb thinking there, as we don’t, when we use a metal or mineral — except in very rare circumstances — take it off planet. We move it around a bit, no more. But the claim really is that we should abstract, for use, no more than is naturally added back each year.

So, the correct limitation on our minerals use is how much magma volcanoes add each year.

No, really, humanity can use no more earth than gets thrown out of a volcano each year. That’s it. To use more would mean that we are depleting the stock and that’s not sustainable, see?

April 21, 2024

How The Channel Tunnel Works

Practical Engineering

Published Jan 16, 2024Let’s dive into the engineering and construction of the Channel Tunnel on its 30th anniversary.

It is a challenging endeavor to put any tunnel below the sea, and this monumental project faced some monumental hurdles. From complex cretaceous geology, to managing air pressure, water pressure, and even financial pressure, there are so many technical details I think are so interesting about this project.

(more…)

April 22, 2022

QotD: George Carlin’s appropriate-for-Earth-Day monologue

Let me tell you about endangered species, all right? Saving endangered species is just one more arrogant attempt by humans to control nature. It’s arrogant meddling. It’s what got us in trouble in the first place. Doesn’t anybody understand that? Interfering with nature. Over 90%, way over 90% of all the species that have ever lived on this planet, ever lived, are gone. They’re extinct. We didn’t kill them all. They just disappeared. That’s what nature does.

We’re so self-important. So self-important. Everybody’s going to save something now. “Save the trees, save the bees, save the whales, save those snails.” And the greatest arrogance of all: save the planet. What? Are these fucking people kidding me? Save the planet, we don’t even know how to take care of ourselves yet. We haven’t learned how to care for one another, we’re gonna save the fucking planet?

I’m getting tired of that shit. Tired of that shit. I’m tired of fucking Earth Day, I’m tired of these self-righteous environmentalists, these white, bourgeois liberals who think the only thing wrong with this country is there aren’t enough bicycle paths. People trying to make the world safe for their Volvos. Besides, environmentalists don’t give a shit about the planet. They don’t care about the planet. Not in the abstract they don’t. You know what they’re interested in? A clean place to live. Their own habitat. They’re worried that some day in the future, they might be personally inconvenienced. Narrow, unenlightened self-interest doesn’t impress me.

Besides, there is nothing wrong with the planet. Nothing wrong with the planet. The planet is fine. The PEOPLE are fucked. Difference. Difference. The planet is fine. Compared to the people, the planet is doing great. Been here four and a half billion years. Did you ever think about the arithmetic? The planet has been here four and a half billion years. We’ve been here, what, a hundred thousand? Maybe two hundred thousand? And we’ve only been engaged in heavy industry for a little over two hundred years. Two hundred years versus four and a half billion. And we have the CONCEIT to think that somehow we’re a threat? That somehow we’re gonna put in jeopardy this beautiful little blue-green ball that’s just a-floatin’ around the sun?

The planet has been through a lot worse than us. Been through all kinds of things worse than us. Been through earthquakes, volcanoes, plate tectonics, continental drift, solar flares, sun spots, magnetic storms, the magnetic reversal of the poles … hundreds of thousands of years of bombardment by comets and asteroids and meteors, worlwide floods, tidal waves, worldwide fires, erosion, cosmic rays, recurring ice ages … And we think some plastic bags, and some aluminum cans are going to make a difference? The planet … the planet … the planet isn’t going anywhere. WE ARE!

We’re going away. Pack your shit, folks. We’re going away. And we won’t leave much of a trace, either. Thank God for that. Maybe a little styrofoam. Maybe. A little styrofoam. The planet’ll be here and we’ll be long gone. Just another failed mutation. Just another closed-end biological mistake. An evolutionary cul-de-sac. The planet’ll shake us off like a bad case of fleas. A surface nuisance.

You wanna know how the planet’s doing? Ask those people at Pompeii, who are frozen into position from volcanic ash, how the planet’s doing. You wanna know if the planet’s all right, ask those people in Mexico City or Armenia or a hundred other places buried under thousands of tons of earthquake rubble, if they feel like a threat to the planet this week. Or how about those people in Kilauea, Hawaii, who built their homes right next to an active volcano, and then wonder why they have lava in the living room.

The planet will be here for a long, long, LONG time after we’re gone, and it will heal itself, it will cleanse itself, ’cause that’s what it does. It’s a self-correcting system. The air and the water will recover, the earth will be renewed, and if it’s true that plastic is not degradable, well, the planet will simply incorporate plastic into a new pardigm: the earth plus plastic. The earth doesn’t share our prejudice towards plastic. Plastic came out of the earth. The earth probably sees plastic as just another one of its children. Could be the only reason the earth allowed us to be spawned from it in the first place. It wanted plastic for itself. Didn’t know how to make it. Needed us. Could be the answer to our age-old egocentric philosophical question, “Why are we here?” Plastic … asshole.

So, the plastic is here, our job is done, we can be phased out now. And I think that’s begun. Don’t you think that’s already started? I think, to be fair, the planet sees us as a mild threat. Something to be dealt with. And the planet can defend itself in an organized, collective way, the way a beehive or an ant colony can. A collective defense mechanism. The planet will think of something. What would you do if you were the planet? How would you defend yourself against this troublesome, pesky species? Let’s see … Viruses. Viruses might be good. They seem vulnerable to viruses. And, uh … viruses are tricky, always mutating and forming new strains whenever a vaccine is developed. Perhaps, this first virus could be one that compromises the immune system of these creatures. Perhaps a human immunodeficiency virus, making them vulnerable to all sorts of other diseases and infections that might come along. And maybe it could be spread sexually, making them a little reluctant to engage in the act of reproduction.

Well, that’s a poetic note. And it’s a start. And I can dream, can’t I? See I don’t worry about the little things: bees, trees, whales, snails. I think we’re part of a greater wisdom than we will ever understand. A higher order. Call it what you want. Know what I call it? The Big Electron. The Big Electron … whoooa. Whoooa. Whoooa. It doesn’t punish, it doesn’t reward, it doesn’t judge at all. It just is. And so are we. For a little while.

George Carlin, “The arrogance of mankind”.

November 7, 2020

Misunderstanding what is meant by “mineral reserves”

It seems to happen almost as regularly as Old Faithful, as someone blows a virtual gasket over the reserves of this or that mineral “running out” in x number of years. Tim Worstall explains why this is a silly misunderstanding of what the term “mineral reserves” actually means:

“Aerial view of a small mine near Mt Isa Queensland.” by denisbin is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

It’s not exactly unusual to see some environmental type running around screaming because mineral reserves are about to run out. The Club of Rome report, the EU’s “circular economy” ideas, Blueprint for Survival, they’re all based upon the idea that said reserves are going to run out.

They look at the usual listing (USGS, here) and note that at the current rate of usage reserves will run out in 30 to 50 years. Entirely correct they are too. It’s the next step which is such drivelling idiocy. For the claim then becomes that we will run out of those metals, those minerals, when the reserves do. This being idiot bollocks.

For a mineral reserve is, as best colloquial language can put it, the stuff we’ve prepared for use in the next few decades. Like, say, 30 to 50 years. That we’re going to run out of what we’ve got prepared isn’t a problem. For we’ve an entire industry, mining, whose job to to go prepare some more for us to use.

[…] A mineral reserve is something created by the mining company. Created by measuring, testing, test extracting and proving that the mineral can be processed, using current technology, at current prices, and produce a profit. Proving that this is not just dirt but is in fact ore.

Mineral reserves are things we humans make, not things that exist.

May 26, 2019

Our nuclear epoch

In Quillette, Michael Shellenberger outlines the discussion about the advent of nuclear energy marking a new age:

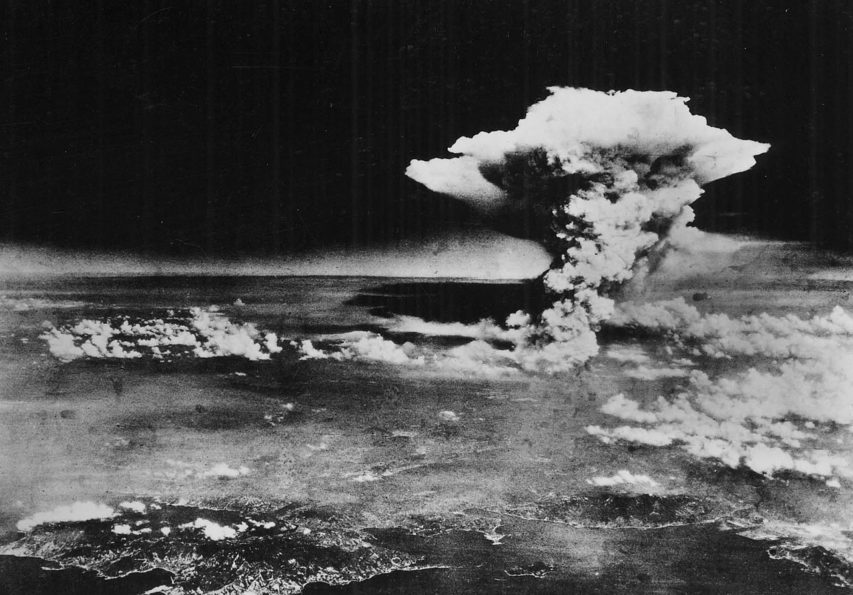

Atomic cloud over Hiroshima, taken from “Enola Gay” flying over Matsuyama, Shikoku, 6 August, 1945.

US Army Air Force photo via Wikimedia Commons.

The age of humans may soon be known as the age of nuclear.

For two decades, scientists have debated whether we are living in a new geological epoch. They appear to have decided that we are and that the invention of nuclear energy should mark its beginning.

Twenty-nine of the 34 members of the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) voted this week to declare the invention and testing of nuclear weapons as the beginning of the Anthropocene or geological age of humans. The two other main contenders for demarcating the start of the epoch were the rise of agriculture, which radically altered landscapes, and the birth of the industrial revolution, which has accelerated climate change.

The 1945 explosion of nuclear weapons at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the radioactive fallout from outdoor nuclear weapons testing, which continued until 1963, is physically embedded in glacial ice and earth sedimentation. Advocates for the invention of nuclear as the best way to mark the beginning of the human age note that, unlike anything done by hunter-gatherers, agriculturalists, or industrialists, nuclear activity leaves a human trace in the geology of Earth. “It is distinguishable,” argues Zalasiewicz. “It is distinctive.”

In their decision, the AWG scientists are implicitly recognizing that nuclear energy is a permanent feature of human civilization, like fire, agriculture, and gunpowder. As such, the decision by scientists to recognize nuclear as a revolutionary technology could help humankind to finally accept the technology along with its potential to lift all humans out of poverty, protect the natural environment, and end war as we know it.

June 1, 2018

Pushing back the beginnings of life on Earth

In Wired, Rebecca Boyle discusses the fossil record of life and how recent discoveries keep moving the date further and further back in Earth’s history:

In the arid, sun-soaked northwest corner of Australia, along the Tropic of Capricorn, the oldest face of Earth is exposed to the sky. Drive through the northern outback for a while, south of Port Hedlund on the coast, and you will come upon hills softened by time. They are part of a region called the Pilbara Craton, which formed about 3.5 billion years ago, when Earth was in its youth.

Look closer. From a seam in one of these hills, a jumble of ancient, orange-Creamsicle rock spills forth: a deposit called the Apex Chert. Within this rock, viewable only through a microscope, there are tiny tubes. Some look like petroglyphs depicting a tornado; others resemble flattened worms. They are among the most controversial rock samples ever collected on this planet, and they might represent some of the oldest forms of life ever found.

Last month, researchers lobbed another salvo in the decades-long debate about the nature of these forms. They are indeed fossil life, and they date to 3.465 billion years ago, according to John Valley, a geochemist at the University of Wisconsin. If Valley and his team are right, the fossils imply that life diversified remarkably early in the planet’s tumultuous youth.

The fossils add to a wave of discoveries that point to a new story of ancient Earth. In the past year, separate teams of researchers have dug up, pulverized and laser-blasted pieces of rock that may contain life dating to 3.7, 3.95 and maybe even 4.28 billion years ago. All of these microfossils — or the chemical evidence associated with them — are hotly debated. But they all cast doubt on the traditional tale.

As that story goes, in the half-billion years after it formed, Earth was hellish and hot. The infant world would have been rent by volcanism and bombarded by other planetary crumbs, making for an environment so horrible, and so inhospitable to life, that the geologic era is named the Hadean, for the Greek underworld. Not until a particularly violent asteroid barrage ended some 3.8 billion years ago could life have evolved.

But this story is increasingly under fire. Many geologists now think Earth may have been tepid and watery from the outset. The oldest rocks in the record suggest parts of the planet’s crust had cooled and solidified by 4.4 billion years ago. Oxygen in those ancient rocks suggest the planet had water as far back as 4.3 billion years ago. And instead of an epochal, final bombardment, meteorite strikes might have slowly tapered off as the solar system settled into its current configuration.

December 10, 2017

QotD: Failures of scientific consensus

In past centuries, the greatest killer of women was fever following childbirth. One woman in six died of this fever. In 1795, Alexander Gordon of Aberdeen suggested that the fevers were infectious processes, and he was able to cure them. The consensus said no. In 1843, Oliver Wendell Holmes claimed puerperal fever was contagious, and presented compelling evidence. The consensus said no. In 1849, Semmelweiss demonstrated that sanitary techniques virtually eliminated puerperal fever in hospitals under his management. The consensus said he was a Jew, ignored him, and dismissed him from his post. There was in fact no agreement on puerperal fever until the start of the twentieth century. Thus the consensus took one hundred and twenty five years to arrive at the right conclusion despite the efforts of the prominent “skeptics” around the world, skeptics who were demeaned and ignored. And despite the constant ongoing deaths of women.

There is no shortage of other examples. In the 1920s in America, tens of thousands of people, mostly poor, were dying of a disease called pellagra. The consensus of scientists said it was infectious, and what was necessary was to find the “pellagra germ.” The US government asked a brilliant young investigator, Dr. Joseph Goldberger, to find the cause. Goldberger concluded that diet was the crucial factor. The consensus remained wedded to the germ theory. Goldberger demonstrated that he could induce the disease through diet. He demonstrated that the disease was not infectious by injecting the blood of a pellagra patient into himself, and his assistant. They and other volunteers swabbed their noses with swabs from pellagra patients, and swallowed capsules containing scabs from pellagra rashes in what were called “Goldberger’s filth parties.” Nobody contracted pellagra. The consensus continued to disagree with him. There was, in addition, a social factor — southern States disliked the idea of poor diet as the cause, because it meant that social reform was required. They continued to deny it until the 1920s. Result — despite a twentieth century epidemic, the consensus took years to see the light.

Probably every schoolchild notices that South America and Africa seem to fit together rather snugly, and Alfred Wegener proposed, in 1912, that the continents had in fact drifted apart. The consensus sneered at continental drift for fifty years. The theory was most vigorously denied by the great names of geology — until 1961, when it began to seem as if the sea floors were spreading. The result: it took the consensus fifty years to acknowledge what any schoolchild sees.

And shall we go on? The examples can be multiplied endlessly. Jenner and smallpox, Pasteur and germ theory. Saccharine, margarine, repressed memory, fiber and colon cancer, hormone replacement therapy. The list of consensus errors goes on and on.

Finally, I would remind you to notice where the claim of consensus is invoked. Consensus is invoked only in situations where the science is not solid enough. Nobody says the consensus of scientists agrees that E=mc2. Nobody says the consensus is that the sun is 93 million miles away. It would never occur to anyone to speak that way.

Michael Crichton, “Aliens Cause Global Warming”: the Caltech Michelin Lecture, 2003-01-17.

January 2, 2017

“Honest scientific discourse and debate is often rendered impossible in the face of the ‘new catastrophism'”

It’s not your imagination — we really do seem to be careening from one ecological disaster to another, all caused by thoughtless human action … well, that’s what the activists are constantly saying:

What is patently obvious from reviewing Canada’s ancient history is that scientists still do not have an adequate understanding of Earth’s complex systems on which to base sound economic and environmental policy. From the upper reaches of the atmosphere to the depths of the oceans onwards to the deep interior of the planet our knowledge of complex earth systems is still rather rudimentary. Huge areas of our planet are inaccessible and are little known scientifically. There is still also much to learn from reading the rock record of how our planet functioned in the past.

In so many areas, we simply don’t know enough of how our planet functions.

And yet……

Scarcely a day goes past without some group declaring the next global environmental crisis; we seemingly stagger from one widely proclaimed crisis to another each one (so we are told) with the potential to severely curtail or extinguish civilization as we know it. It’s an all too familiar story often told by scientists who cross over into advocacy and often with the scarcely-hidden sub-text that they are the only ones with the messianic foresight to see the problem and create a solution. Much of our science is what we would call ‘crisis-driven’ where funding, politics and the media are all intertwined and inseparable generating a corrupting and highly corrosive influence on the scientific method and its students. If it doesn’t bleed it doesn’t lead is the new yardstick with which to measure the overall significance of research.

Charles Darwin ushered in a new era of thinking where change was expected and necessary. Our species as are all others, is the product of ongoing environmental change and adaption to varying conditions; the constancy of change. In the last 15 years or so however, we have seemingly reverted to a pre-Darwinian mode of a fixed ‘immutable Earth’ where any change beyond some sort of ‘norm’ is seen in some quarters as unnatural, threatening and due to our activities, usually with the proviso of needing ‘to act now to save the planet.’ Honest scientific discourse and debate is often rendered impossible in the face of the ‘new catastrophism.’

Trained as geologists in the knowledge of Earth’s immensely long and complex history we appreciate that environmental change is normal. For example, rivers and coastlines are not static. Those coasts, in particular, that consist of sandy strand-plains and barrier-lagoon systems are continually evolving as sand is moved by the waves and tides. Cyclonic storms (hurricanes), a normal component of the weather in many parts of the world, are particularly likely to cause severe erosion. When recent events such as Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy cause catastrophic damage, and spring storms cause massive flooding in Calgary or down the Mississippi valley, and droughts and wildfires affect large areas of the American SW these events are blamed on a supposed increase in the severity of extreme weather events brought about by climate change. In fact, they just reflect the working of statistical probability and long term climate cyclicity. Such events have happened in the past as part of ongoing changes in climate but affected fewer people. That the costs of weather and climate-related damage today are far greater is not because of an increased frequency of severe weather but the result of humans insisting on congregating and living in places that, while attractive, such as floodplains, mountain sides and beautiful coastlines, are especially vulnerable to natural disasters. Promises of a more ‘stable future’ if we can only prevent climate change are hopelessly misguided and raise unnatural expectations by being willfully ignorant of the natural workings of the planet. Climate change is the major issue for which more geological input dealing with the history of past climates would contribute to a deeper understanding of the nature of change and what we might expect in the future. The past climate record suggests in fact that for much of the Earth’s surface future cooling is the norm. Without natural climate change Canada would be buried under ice 3 km thick; that is it normal state for most of the last 2.5 million years with 100,000 years-long ice ages alternating with brief, short-lived interglacials such as the present which is close to its end.

H/T to Kate at SDA for the link.

November 14, 2013

Scientific facts and theories

Christopher Taylor wants to help you avoid mis-using the word “fact” when you’re talking about “theories”:

These days, criticizing or questioning statements on science can get you called an idiot or even a heretic; science has become a matter of religious faith for some. If a scientist said it, they believe it, and that’s that. Yet the very nature about science is not to be an authoritative voice, but a method of inquiry; science is about asking questions and wondering if something is valid and factual, not a system of producing absolute statements of unquestioned truth.

It is true that people need that source of truth and it is true that we’re all inescapably religious creatures, so that will find an outlet somewhere. Science just isn’t the proper outlet for it.

[…]

The problem is that there’s no way to test or confirm this theory [plate tectonics]. You can make a model and see it work, you can check out types of rock and examine fault lines, and you can make measurements, but that’s only going to tell you small portions of information in very limited time frames. Because the earth is so huge, and because there are so very many different pressures and influences on everything on a planet, you can’t be sure without observation over time.

And since the theory posits that it would take millions of years to really demonstrate this to be true, humanity cannot test it enough to be certain. So all we’re left with is a scientific theory: a functional method of interpreting data. In other words, it cannot be properly or accurately describe as fact.

This is true about other areas. The word “fact” is thrown around so casually with science and is defended angrily by people who really ought to know better. Cosmology does this a lot. Its a fact that the universe is expanding from an unknown central explosive point (although there is a fair amount of data that’s throwing this into question). We can’t know because we can’t have enough data and there hasn’t been long enough to really test this.

Michael Crichton’s criticism of global warming was along these lines. He didn’t deny anything, he just said its too big and complex a system that we understand far too little about to even attempt to make any absolute or authoritative statements about it. Science has gotten us far beyond our ability to properly measure or interpret the data at hand, but some still keep trying to make absolute statements anyway.

[…]

And that’s the heart of a scientific theory. It isn’t like a geometric theorem (a statement or formula that can be deduced from the axioms of a formal system by means of its rules of inference), or a theory that Sherlock Holmes might develop (a proposed explanation whose status is still conjectural). A scientific theory is a system of interpreting data (a coherent group of general propositions used as principles of explanation for a class of phenomena). It’s a step beyond a hypothesis, which is simply speculation or a guess, but is not proven fact.

Confusing theory with fact is really not excusable for an educated person, but some theories are so wedded to worldviews and hopes that they become a matter of argument and even rage. Questioning that theory means you’re an idiot, uneducated, worthless. If you doubt this theory, you’re clearly someone who is wrong about everything and should be totally ignored in life, even showered with contempt.

For all its rich vocabulary, English fails to correctly differentiate among the various uses of the word “theory”, which allows propagandists and outright frauds to confuse the issues and obscure the difference between what science can say about an issue and what believers desperately want to be true.

July 10, 2013

Next up on our agenda of things to panic about is “peak water”

sp!ked editor Rob Lyons explains that “peak water” just isn’t something to worry too much about:

Disappointed by the failure of the peak-oil disaster to come to fruition, our doom-mongering, Malthusian friends have alighted on other scary narratives to confirm their suspicions of humanity as a rapacious blight on the planet. Their latest is ‘peak water’.

On the face of it, peak water is a boneheaded concept on a planet where two thirds of the surface is covered in, er, water. According to the US Geological Survey, there are 332 million cubic miles of water on Earth. What we tend to need, however, is not sea water but fresh water, of which there is much less: nearer 2.5 million cubic miles. And much of that is too deep underground to be accessed. Surface water in rivers and lakes is a small fraction of overall fresh water: 22,339 cubic miles. Handily, though, natural processes cause sea water to evaporate and form clouds, which then dump their contents on to land — so in most populated parts of the world there is currently sufficient water to supply our needs in an endlessly renewable way. As for the future, it is clear there is no shortage of H2O on the planet. What we really have is a shortage of cheap energy and the necessary technology to take advantage of the salinated stuff.

The ‘peak water’ theorists focus on groundwater supplies that are either being used faster than they are replenished, or supplies that are not replenished at all: so-called ‘fossil water’. According to leading environmentalist Lester Brown, writing in the Guardian last weekend, the rapid exhaustion of these supplies in some parts of the world is leading to the decline of food production. And at a time of fast-growing populations, this apparently promises disaster for these countries.

But often, the problem is a political rather than a practical one. [. . .]

In reality, all of the fixes that apply to peak oil also apply to peak water. New technology may make water desalination far cheaper than it is now, a claim being made for new water filtration methods based on nanotechnology. Better use of water in irrigation, through careful management of when and how water is applied to crops, could cut usage dramatically — something that is already happening in dry countries such as Israel and Australia and in parts of the US. Current uses of water, like flush toilets, may be superseded in places where water is in high demand. Through civil engineering projects, water can be shifted from places where it is plentiful to places where it is needed most, something societies have been doing for thousands of years.

July 6, 2013

Matt Ridley on the “shale cornucopia”

It’s a big deal. A really big deal:

A new report (The Shale Oil Boom: a US Phenomenon) by Leonardo Maugeri, of Harvard University, sets out just how astonishing this second shale revolution already is. After falling for 30 years, US oil production rocketed upwards in the past three years. In 1995 the Bakken field was reckoned by the US Geological Survey to hold a trivial 151 million barrels of recoverable oil. In 2008 this was revised upwards to nearly 4 billion barrels; two months ago that number was doubled. It is a safe bet that it will be revised upwards again.

The big reason for the upwards revisions is technology rather than discovery. Thanks to faster and cheaper drilling (which means less-rich rocks can be profitable) and things such as “zipper fracturing”, where two parallel wells are drilled and alternately fractured to help to release oil for each other, the oil recovery rate is rising from 2 per cent towards 10 per cent in places. Gas is now nearer 30 per cent. Well productivity has doubled in five years.

Now the Bakken is being eclipsed by an even more productive shale formation in southern Texas called the Eagle Ford. Texas, which already produces conventional oil, has doubled its oil production in just over two years and by the end of this year will exceed Venezuela, Kuwait, Mexico and Iraq as an oil “nation”.

[. . .]

Mr Maugeri calculates that at $85 a barrel most shale oil wells repay their capital costs in a year. He estimates that even if oil prices fall steadily to $65 in five years, shale oil production will treble in the US because of increasing productivity per well and the easing of transport bottlenecks. By 2017, he thinks, America will be producing nearly 11 billion barrels a day [correction 11 million], equal to its previous peak in 1970. It would need much less in the way of imports. US oil imports peaked at 60 per cent in 2005 and will be below 40 per cent this year.

Internationally the effect is very different for oil compared with gas. Gas is costly to export by sea, requiring liquefaction. This roughly doubles the cost of it, meaning that America’s cheap shale gas boosts its economy at home, and gives it a competitive advantage in attracting energy-intensive industries. (US gas prices are a third or a quarter of what they are here.) Mexico, too, is benefiting because of having a land border with America and pipelines.

[. . .]

There would be losers. America’s falling appetite for imports may hit Nigeria and Angola harder than the Middle East because of the types of oil they produce, while Canada and Venezuela, whose tarry oil sands are high-cost, would also suffer if oil prices fell. But every oil producer would eventually feel the effect of this falling US demand, so there is no doubting the downward pressure on world oil prices that this revolution is likely to cause.

July 3, 2012

Bad news (for panicmongers, anyway)

In the Guardian, George Monbiot (known to his detractors as “The Great Moonbat”) admits the terrible truth. He was wrong, again:

The facts have changed, now we must change too. For the past 10 years an unlikely coalition of geologists, oil drillers, bankers, military strategists and environmentalists has been warning that peak oil — the decline of global supplies — is just around the corner. We had some strong reasons for doing so: production had slowed, the price had risen sharply, depletion was widespread and appeared to be escalating. The first of the great resource crunches seemed about to strike.

Among environmentalists it was never clear, even to ourselves, whether or not we wanted it to happen. It had the potential both to shock the world into economic transformation, averting future catastrophes, and to generate catastrophes of its own, including a shift into even more damaging technologies, such as biofuels and petrol made from coal. Even so, peak oil was a powerful lever. Governments, businesses and voters who seemed impervious to the moral case for cutting the use of fossil fuels might, we hoped, respond to the economic case.

[. . .]

Peak oil hasn’t happened, and it’s unlikely to happen for a very long time.

A report by the oil executive Leonardo Maugeri, published by Harvard University, provides compelling evidence that a new oil boom has begun. The constraints on oil supply over the past 10 years appear to have had more to do with money than geology. The low prices before 2003 had discouraged investors from developing difficult fields. The high prices of the past few years have changed that.

August 29, 2011

American Chemical Society presentation or science fiction convention panel?

If all you had to go on was the first paragraph, it’d sure sound like the SF convention, not the ACS expo:

How do diamonds the size of potatoes shoot up at 40 miles per hour from their birthplace 100 miles below Earth’s surface? Does a secret realm of life exist inside the Earth? Is there more oil and natural gas than anyone dreams, with oil forming not from the remains of ancient fossilized plants and animals near the surface, but naturally deep, deep down there? Can the greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide, be transformed into a pure solid mineral?

Those are among the mysteries being tackled in a real-life version of the science fiction classic, A Journey to the Center of the Earth, that was among the topics of a presentation here today at the 242nd National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS). Russell Hemley, Ph.D., said that hundreds of scientists will work together on an international project, called the Deep Carbon Observatory (DCO), to probe the chemical element that’s in the news more often than perhaps any other. That’s carbon as in carbon dioxide.