The problem with all “models of the world”, as the video puts it, is that they ignore two vitally important factors. First, models can only go so deep in terms of the scale of analysis to attempt. You can always add layers — and it is never clear when a layer that is completely unseen at one scale becomes vitally important at another. Predicting higher-order effects from lower scales is often impossible, and it is rarely clear when one can be discarded for another.

Second, the video ignores the fact that human behavior changes in response to circumstance, sometimes in radically unpredictable ways. I might predict that we will hit peak oil (or be extremely wealthy) if I extrapolate various trends. However, as oil becomes scarce, people discover new ways to obtain it or do without it. As people become wealthier, they become less interested in the pursuit of wealth and therefore become poorer. Both of those scenarios, however, assume that humanity will adopt a moral and optimistic stance. If humans become decadent and pessimistic, they might just start wars and end up feeding off the scraps.

So, interestingly, what the future looks like might be as much a function of the music we listen to, the books we read, and the movies we watch when we are young as of the resources that are available.

Note that the solution they propose to our problems is internationalization. The problem with internationalizing everything is that people have no one to appeal to. We are governed by a number of international laws, but when was the last time you voted in an international election? How do you effect change when international policies are not working out correctly? Who do you appeal to?

The importance of nationalism is that there are well-known and generally-accepted procedures for addressing grievances with the ruling class. These international clubs are generally impervious to the appeals (and common sense) of ordinary people and tend to promote virtue-signaling among the wealthy class over actual virtue or solutions to problems.

Jonathan Bartlett, quoted in “1973 Computer Program: The World Will End In 2040”, Mind Matters News, 2019-05-31.

December 9, 2022

QotD: Computer models of “the future”

September 29, 2022

Nostradamus

In the latest post at Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander considers prophecy “From Nostradamus to Fukuyama”. Here’s the section on Nostradamus (because I don’t have a lot of time for Fukuyama, you’ll have to read the rest at ACX):

“House of Nostradamus in Salon, France. Now a museum.” by photographymontreal is marked with Public Domain Mark 1.0 .

Nostradamus was a 16th century French physician who claimed to be able to see the future.

(never trust doctors who dabble in futurology, that’s my advice)

His method was: read books of other people’s prophecies and calculate some astrological charts, until he felt like he had a pretty good idea what would happen in the future. Then write it down in the form of obscure allusions and multilingual semi-gibberish, to placate religious authorities (who apparently hated prophecies, but loved prophecies phrased as obscure allusions and multilingual semi-gibberish).

In 1559, he got his big break. During a jousting match, a count killed King Henry II of France with a lance through the visor of his helmet. Years earlier, Nostradamus had written:

The young lion will overcome the older one,

On the field of combat in a single battle;

He will pierce his eyes through a golden cage,

Two wounds made one, then he dies a cruel deathThe nobleman was a bit younger than the king, supposedly they both had lions on their shield (false), maybe King Henry was wearing a golden helmet (I can’t find evidence for this, but as a consolation prize please accept this picture of his amazing parade armor), and his slow agonizing death over ten days from his wounds was pretty cruel. Seems like a match, sort of. Anyway, for the next five hundred years lots of people were really into Nostradamus and spent goodness knows how many brain cycles trying to interpret his incomprehensible quatrains.

The basic Nostradamic method was:

Write 942 vague and incomprehensible quatrains, out of order and without any dates.

Whenever something happens, say “that sounds a lot like quatrain #143!” or “quatrain #558 predicted that”

Prophet

For example, prophecy 106:

Near the gates and within two cities

There will be two scourges the like of which was never seen,

Famine within plague, people put out by steel,

Crying to the great immortal God for reliefThis is an okay match for the atomic bombs, in the sense that there were two cities where something really bad happened. But read on to prophecy 107:

Amongst several transported to the isles,

One to be born with two teeth in his mouth

They will die of famine the trees stripped,

For them a new King issues a new edict.… and it starts to sound like he’s just kind of saying random stuff and some of it’s sticking by sheer luck.

A few prophecies sound more impressive than this, eg:

The lost thing is discovered, hidden for many centuries.

Pasteur will be celebrated almost as a god-like figure.

This is when the moon completes her great cycle,

but by other rumours he shall be dishonouredThis seems to name Pasteur, who was indeed a celebrated discoverer of things. And Nostradamus scholars note that a historian accused Pasteur of plagiarism in 1995, which is a kind of dishonorable rumor. But the work here is being done by the translator: Pasteur is just French for “pastor”, and an honest translation would have just said “the pastor will be celebrated …”, which is in tune with all his other vague allusions to things happening.

The blood of the just will be demanded of London

Burnt by fire in the year ’66

The ancient Lady will fall from her high place

And many of the same sect will be killed.Seems like a match for the London fire of 1666. But again checking the original French and the commentators, the second line is more properly “burnt by fire in 23 the 6”, which a fanciful translator rounded off to 20 * 3 + 6 = 66 and then assumed was a year. The experts say that this is really a coded reference to 23 Protestants being burned, in groups of six, during Nostradamus’ lifetime (many of his quatrains are references to past or present events, for some reason). This sounds more compatible with the “many of the same sect will be killed” ending.

I had a weird experience writing the end of this first part of the post. When I was a kid, reading through my parents’ old books, I came across an weird almanac from the 70s that had a section on Nostradamus. It listed some of his most famous prophecies, including the ones above, but also (reconstructing from memory and probably getting some things wrong, sorry):

The way of life according to Thomas More

Will give way to another more sweet and seductive

In the land of cold winds that first gave it birth

Without strife, without a war it will fall… and the 70s almanac interpreted this as meaning Soviet communism would fall peacefully. Reading this in 1995 or whenever it was I read it, a few years after Soviet communism did fall peacefully, I was really impressed: this is the only example I know where someone used a Nostradamus quatrain to predict something before it happened.

But I searched for the exact text so I could include the correct version in this essay, and I didn’t find it — this is none of Nostradamus’ 942 prophecies! The almanac authors must have made it up, or unwittingly copied it from someone else who did.

But I remember this very clearly — the almanac was from 1970-something. So how did the faker know Russian communism would collapse?

The moral of the story is: just because Nostradamus wasn’t a real prophet, doesn’t mean nobody else is.

June 18, 2021

Feeding “the masses”

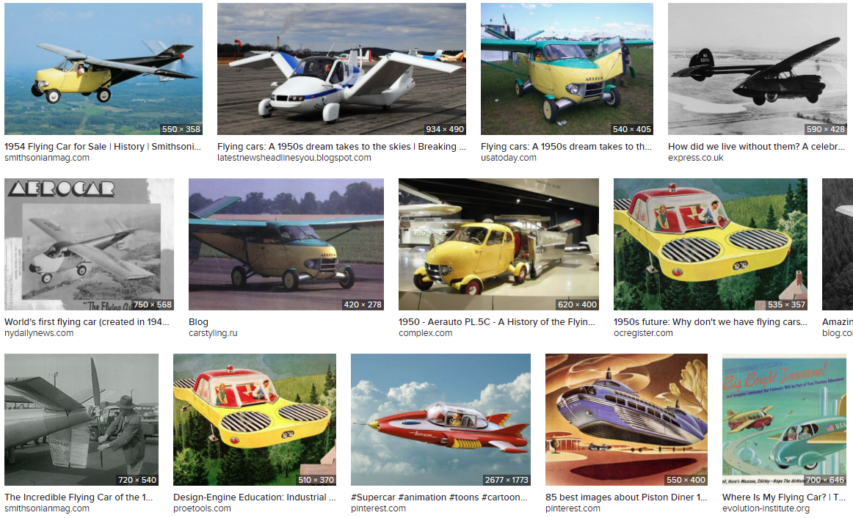

Sarah Hoyt looked at the perennial question “Dude, where’s my (flying) car?” and the even more relevant to most women “Where’s my automated house?”:

The cry of my generation, for years now, has been: “Dude, where’s my flying car?”

My friend Jeff Greason is fond of explaining that as an engineering problem, a flying car is no issue at all. It is as a legal problem that flying cars get interesting, because of course the FAA won’t let such a thing exist without clutching it madly and distorting it with its hands made of bureaucracy and crazy. (Okay, he doesn’t put it that way, but I do.)

[…]

But in all this, I have to say: Dude, where’s my automated house?

It was fifteen years ago or so, while out at lunch with an older writer friend, that she said “We always thought that when it came to this time, there would be communal lunch rooms and cafeterias that would do all the cooking so women would be free to work.”

I didn’t say anything. I knew our politics weren’t congruent, but really the only societies that managed that “Cafeterias, where everyone eats” were the most totalitarian ones, and that food was nothing you wanted to eat. If there was food. Because the only way to feed everyone industrial style is to take away their right to choose how to feed themselves and what to eat. And that, over an entire nation, would be a nightmare. Consider the eighties, when the funny critters decided that we should all live on a Russian Peasant diet of carbs, carbs and more carbs. Potatoes were healthy and good for you, and you should live on them.

It will surprise you to know – not — that just as with the mask idiocy, no study of any kind supports feeding the population on mostly vegetables, much less starches. What those whole “recommendations” were based on was “diet for a small planet” and the bureaucrats invincible ignorance, stupidity and assumption of their own intelligence and superiority. I.e. most of what they knew — that population was exploding, that people would soon be starving, that growing vegetables is less taxing on the environment and produces more calories than growing animals to eat — just wasn’t so. But they “knew” and by gum were going to force everyone to follow “the plan”. (BTW one of the ways you know that Q-Anon is in fact a black ops operation from the other side; no one on the right in this country trusts a plan, much less one that can’t be shared or discussed.) Then the complete idiots were shocked, surprised, nay, astonished when their proposed diet led to an “epidemic of obesity” and diabetes. Even though anyone who suffered through the peasant diet in communist countries, could have told the that’s where it would lead, and to both obesity and Mal-nutrition at once.

So, yeah, communal cafeterias are not a solution to anything.

My concern about the “automated house of the future” is nicely prefigured by the “wonders” of Big Tech surveillance devices we’ve voluntarily imported into our homes for the convenience, while awarding untold volumes of free data for the tech firms to market. Plus, the mindset that “you must be online at all times” that many/most of these devices require means you’re out of luck if your internet connection is a bit wobbly (looking at you, Rogers).

June 7, 2021

Dude, where’s my (flying) car?

The latest of the reader-contributed book reviews at Scott Alexander’s Astral Codex Ten looks at Where is my Flying Car? by J. Storrs Hall:

What went wrong in the 1970s? Since then, growth and productivity have slowed, average wages are stagnant, visible progress in the world of “atoms” has practically stopped — the Great Stagnation. About the only thing that has gone well are computers. How is it that we went from the typewriter to the smartphone, but we’re still using practically the same cars and airplanes?

Where is my Flying Car? by J. Storrs Hall, is an attempt to answer that question. His answer is: the Great Stagnation was caused by energy usage flatlining, which was caused by our failure to switch to nuclear energy, which was caused by excessive regulation, which was caused by “green fundamentalism”.

Three hundred years ago, we burned wood for energy. Then there was coal and the steam engine, which gave us the Industrial Revolution. Then there was oil and gas, giving us cars and airplanes. Then there should have been nuclear fission and nanotech, letting you fit a lifetime’s worth of energy in your pocket. Instead, we still drive much the same cars and airplanes, and climate change threatens to boil the Earth.

I initially thought the title was a metaphor — the “flying car” as a standin for all the missing technological progress in the world of “atoms” — but in fact much of the book is devoted to the particular question of flying cars. So look at the issue from the lens of transportation:

Hans Rosling was a world health economist and an indefatigable campaigner for a deeper understanding of the world’s state of development. He is famous for his TED talks and the Gapminder web site. He classifies the wealthiness of the world’s population into four levels:

1. Barefoot. Unable even to afford shoes, they must walk everywhere they go. Income $1 per day. One billion people are at Level 1.

2. Bicycle (and shoes). The $4 per day they make doesn’t sound like much to you and me but it is a huge step up from Level 1. There are three billion people at level 2.

3. The two billion people at Level 3 make $16 a day; a motorbike is within their reach.

4. At $64 per day, the one billion people at Level 4 own a car.

The miracle of the Industrial Revolution is now easily stated: In 1800, 85% of the world’s population was at Level 1. Today, only 9% is. Over the past half century, the bulk of humanity moved up out of Level 1 to erase the rich-poor gap and make the world wealth distribution roughly bell-shaped. The average American moved from Level 2 in 1800, to level 3 in 1900, to Level 4 in 2000. We can state the Great Stagnation story nearly as simply: There is no level 5.

Level 5, in transportation, is a flying car. Flying cars are to airplanes as cars are to trains. Airplanes are fast, but getting to the airport, waiting for your flight, and getting to your final destination is a big hassle. Imagine if you had to bike to a train station to get anywhere (not such a leap of imagination for me in New York City! But it wouldn’t work in the suburbs). What if you had one vehicle that could drive on the road and fly in the sky at hundreds of miles an hour?

Before reading this book, I thought flying cars were just technologically infeasible, because flying takes too much energy. But Hall says we can and have built them ever since the 1930s. They got interrupted by the Great Depression (people were too poor to buy private airplanes), then WWII (airplanes were directed towards the war effort, not the market), then regulation mostly killed the private aviation industry. But technical feasibility was never the problem.

Hall spends a huge fraction of the book on pretty detailed technical discussion of flying cars. For example: the key technical issue is takeoff and landing, and there is a tough tradeoff between convenient takeoff/landing and airspeed (and cost, and ease of operation). It’s interesting reading. But let’s return to the larger issue of nuclear power.

December 28, 2020

The Tiny Monorails That Once Carried James Bond

Tom Scott

Published 21 Sep 2020The Roadmachines Mono-Rail may have been the only truly useful, fit-for-purpose monorail in the world. Of the hundreds that were built, most were never meant for passengers. But they did carry a couple of famous people in their time, including a certain secret agent…

Thank you to the staff and volunteers at the Amberley Museum – Harry and Gerry in particular – for running the monorail specially, and letting me film! The Amberley Museum is a massive industrial heritage museum in the South Downs, and you can find out more about them here: https://www.amberleymuseum.co.uk/

There are lots more videos of Amberley’s rail vehicles at the volunteers’ channel here: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCMHT…

My research is heavily based on David Voice’s Mono-Rail: The History of the Industrial Monorails Made By Road Machines Ltd., Metalair Ltd and Rail Machines Ltd, ISBN 1874422877, available from Adam Gordon Books: http://www.ahgbooks.com/index.php/pro…

Thanks to Derry Faux-Nightingale for the initial idea!

The Tanat Valley Railway in Nantmawr is the home for the Richard Morris collection, more than seventy surviving Roadmachines Mono-Rails: https://www.tanatvalleyrailway.co.uk/…

Also a helpful resource:

https://www.irsociety.co.uk/Archives/…I’m at https://tomscott.com

on Twitter at https://twitter.com/tomscott

and on Instagram as tomscottgo

January 11, 2018

William Gibson: The Gernsback Continuum – Semiotic Ghosts – #8

Extra Credits

Published on Jan 9, 2018Ways that we dream about the world sometimes create a shared vision that we start to believe is real. When William Gibson first explored these “semiotic ghosts” of a pristine American future in the Gernsback Continuum, he showed how these visions of modern technology can separate us from our own reality and the personal meaning our world should hold for us.

October 18, 2017

Wheel of Future History

exurb1a

Published on 16 Oct 2017It’s 2017. No jet packs yet, but 3D printed beer will be here soon so just shhhhhhhhh.

The poem near the end is ripped off from Rudyard Kipling’s “If”. It’s a good one. Check it out ► https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46473/if—

November 27, 2016

QotD: Fabric as technology

In February 1939, Vogue ran a major feature on the fashions of the future. Inspired by the soon-to-open New York World’s Fair, the magazine asked nine industrial designers to imagine what the people of ‘a far Tomorrow’ might wear and why. (The editors deemed fashion designers too of-the-moment for such speculations.) A mock‑up of each outfit was manufactured and photographed for a lavish nine-page colour spread.

You might have seen some of the results online: an evening dress with a see-through net top and strategically placed swirls of gold braid, for instance, or a baggy men’s jumpsuit with a utility belt and halo antenna. Bloggers periodically rediscover a British newsreel of models demonstrating the outfits while a campy narrator (‘Oh, swish!’) makes laboured jokes. The silly get‑ups are always good for self-satisfied smirks. What dopes those old-time prognosticators were!

The ridicule is unfair. Anticipating climate-controlled interiors, greater nudity, more athleticism, more travel and simpler wardrobes, the designers actually got a lot of trends right. Besides, the mock‑ups don’t reveal what really made the predicted fashions futuristic. Looking only at the pictures, you can’t detect the most prominent technological theme.

‘The important improvements and innovations in clothes for the World of Tomorrow will be in the fabrics themselves,’ declared Raymond Loewy, one of the Vogue contributors. His fellow visionaries agreed. Every single one talked about textile advances. Many of their designs specified yet-to-be-invented materials that could adjust to temperature, change colour or be crushed into suitcases without wrinkling. Without exception, everyone foretelling the ‘World of Tomorrow’ believed that an exciting future meant innovative new fabrics.

They all understood something we’ve largely forgotten: that textiles are technology, more ancient than bronze and as contemporary as nanowires. We hairless apes co-evolved with our apparel. But, to reverse Arthur C Clarke’s adage, any sufficiently familiar technology is indistinguishable from nature. It seems intuitive, obvious – so woven into the fabric of our lives that we take it for granted.

Virginia Postrel, “Losing the Thread: Older than bronze and as new as nanowires, textiles are technology — and they have remade our world time and again”, Aeon, 2015-06-05.

March 26, 2016

August 31, 2015

QotD: Artistic memories of other futures

Two exhibitions in New York this season revisit memories of futures past: Nam June Paik’s “Becoming Robot” (which will be at the Asia Society until January 4) looks to a cybernetics-obsessed midcentury avant-garde, while the Guggenheim’s “Reconstructing the Universe” show of Italian futurist works (which has just closed) documented a movement that, while aesthetically quite distinct from Paik’s, is organized around the same essential vision: man’s aspiring to the condition of machine.

[…]

There are occasionally clever pieces: A seated Buddha contemplates a television-and-camera set-up that contemplates him back, the Buddha and his image on the screen suggesting an infinite feedback loop. A reclining Buddha stretches atop two television screens showing a video of a nude woman reclining in the same position. (Paik very often cuts to the root of the avant-garde sensibility: “How do we get some naked chicks in this?”) His robots are still interesting to look at, some of them primitive mechanical assemblages, some of them televisions and other electronic devices piled together anthropomorphically, though the contemporary commercially made robot toys on display for context are at least as interesting, their nameless creators liberated from such pressures as attend those who understand themselves as artists. Though it should be noted that the makers of the Micronaut robot toys I loved as a child were not entirely immune from the puerile sexual obsessions of the so-called avant-garde: This, for example, was on the market long before anybody ever exclaimed: “Drill, baby, drill!”

The Italian futurists, whose love for machines and violence and the machinery of violence and whose hatred of women would do so much to shape the aesthetics of fascism, foresaw a less sexy future than Paik’s, if one that was no less mechanical: Biplanes soar over the Roman Colosseum, cities are fitted together like clockworks, machinery everywhere is ascendant. By the time Mussolini makes his inevitable appearance, he, too, has been reduced to a piece of artillery, his face simply another item in the Italian arsenal, a big, fleshy cannonball.

One of the purposes of art, high or low, is to make visible the philosophical; the fascist understanding of society as one big factory or one big machine was expressed in futurist art.

Kevin D. Williamson, “Futures Trading: We are no longer thinking about the future because we believe we are there”, National Review, 2014-10-01.

January 25, 2015

QotD: TED

Take the curious phenomenon of the TED talk. TED – Technology, Entertainment, Design – is a global lecture circuit propagating “ideas worth spreading”. It is huge. Half a billion people have watched the 1,600 TED talks that are now online. Yet the talks are almost parochially American. Some are good but too many are blatant hard sells and quite a few are just daft. All of them lay claim to the future; this is another futurology land-grab, this time globalised and internet-enabled.

Benjamin Bratton, a professor of visual arts at the University of California, San Diego, has an astrophysicist friend who made a pitch to a potential donor of research funds. The pitch was excellent but he failed to get the money because, as the donor put it, “You know what, I’m gonna pass because I just don’t feel inspired … you should be more like Malcolm Gladwell.” Gladwellism – the hard sell of a big theme supported by dubious, incoherent but dramatically presented evidence – is the primary TED style. Is this, wondered Bratton, the basis on which the future should be planned? To its credit, TED had the good grace to let him give a virulently anti-TED talk to make his case. “I submit,” he told the assembled geeks, “that astrophysics run on the model of American Idol is a recipe for civilisational disaster.”

Bratton is not anti-futurology like me; rather, he is against simple-minded futurology. He thinks the TED style evades awkward complexities and evokes a future in which, somehow, everything will be changed by technology and yet the same. The geeks will still be living their laid-back California lifestyle because that will not be affected by the radical social and political implications of the very technology they plan to impose on societies and states. This is a naive, very local vision of heaven in which everybody drinks beer and plays baseball and the sun always shines.

The reality, as the revelations of the National Security Agency’s near-universal surveillance show, is that technology is just as likely to unleash hell as any other human enterprise. But the primary TED faith is that the future is good simply because it is the future; not being the present or the past is seen as an intrinsic virtue.

Bryan Appleyard, “Why futurologists are always wrong – and why we should be sceptical of techno-utopians: From predicting AI within 20 years to mass-starvation in the 1970s, those who foretell the future often come close to doomsday preachers”, New Statesman, 2014-04-10.

January 20, 2015

QotD: Neuroscientific claims

One last futurological, land-grabbing fad of the moment remains to be dealt with: neuroscience. It is certainly true that scanners, nanoprobes and supercomputers seem to be offering us a way to invade human consciousness, the final frontier of the scientific enterprise. Unfortunately, those leading us across this frontier are dangerously unclear about the meaning of the word “scientific”.

Neuroscientists now routinely make claims that are far beyond their competence, often prefaced by the words “We have found that …” The two most common of these claims are that the conscious self is a illusion and there is no such thing as free will. “As a neuroscientist,” Professor Patrick Haggard of University College London has said, “you’ve got to be a determinist. There are physical laws, which the electrical and chemical events in the brain obey. Under identical circumstances, you couldn’t have done otherwise; there’s no ‘I’ which can say ‘I want to do otherwise’.”

The first of these claims is easily dismissed – if the self is an illusion, who is being deluded? The second has not been established scientifically – all the evidence on which the claim is made is either dubious or misinterpreted – nor could it be established, because none of the scientists seems to be fully aware of the complexities of definition involved. In any case, the self and free will are foundational elements of all our discourse and that includes science. Eliminate them from your life if you like but, by doing so, you place yourself outside human society. You will, if you are serious about this displacement, not be understood. You will, in short, be a zombie.

Bryan Appleyard, “Why futurologists are always wrong – and why we should be sceptical of techno-utopians: From predicting AI within 20 years to mass-starvation in the 1970s, those who foretell the future often come close to doomsday preachers”, New Statesman, 2014-04-10.

January 17, 2015

If anything, Blade Runner was too optimistic

Joey DeVilla posted a few images comparing the dystopian future envisioned in Blade Runner with the modern cityscape of Beijing:

The crowded, dirty Los Angeles of 2019 featured in the 1982 film Blade Runner looks rather pristine compared to the real-life Beijing of 2015.

December 31, 2014

QotD: Dr. Johnson on the future

At another level, futurology implies that we are unhappy in the present. Perhaps this is because the constant, enervating downpour of gadgets and the devices of the marketeers tell us that something better lies just around the next corner and, in our weakness, we believe. Or perhaps it was ever thus. In 1752, Dr Johnson mused that our obsession with the future may be an inevitable adjunct of the human mind. Like our attachment to the past, it is an expression of our inborn inability to live in – and be grateful for – the present.

“It seems,” he wrote, “to be the fate of man to seek all his consolations in futurity. The time present is seldom able to fill desire or imagination with immediate enjoyment, and we are forced to supply its deficiencies by recollection or anticipation.”

Bryan Appleyard, “Why futurologists are always wrong – and why we should be sceptical of techno-utopians: From predicting AI within 20 years to mass-starvation in the 1970s, those who foretell the future often come close to doomsday preachers”, New Statesman, 2014-04-10.

November 25, 2014

When was it exactly that “progress stopped”?

Scott Alexander wrote this back in July. I think it’s still relevant as a useful perspective-enhancer:

The year 1969 comes up to you and asks what sort of marvels you’ve got all the way in 2014.

You explain that cameras, which 1969 knows as bulky boxes full of film that takes several days to get developed in dark rooms, are now instant affairs of point-click-send-to-friend that are also much higher quality. Also they can take video.

Music used to be big expensive records, and now you can fit 3,000 songs on an iPod and get them all for free if you know how to pirate or scrape the audio off of YouTube.

Television not only has gone HDTV and plasma-screen, but your choices have gone from “whatever’s on now” and “whatever is in theaters” all the way to “nearly every show or movie that has ever been filmed, whenever you want it”.

Computers have gone from structures filling entire rooms with a few Kb memory and a punchcard-based interface, to small enough to carry in one hand with a few Tb memory and a touchscreen-based interface. And they now have peripherals like printers, mice, scanners, and flash drives.

Lasers have gone from only working in special cryogenic chambers to working at room temperature to fitting in your pocket to being ubiquitious in things as basic as supermarket checkout counters.

Telephones have gone from rotary-dial wire-connected phones that still sometimes connected to switchboards, to cell phones that fit in a pocket. But even better is bypassing them entirely and making video calls with anyone anywhere in the world for free.

Robots now vacuum houses, mow lawns, clean office buildings, perform surgery, participate in disaster relief efforts, and drive cars better than humans. Occasionally if you are a bad person a robot will swoop down out of the sky and kill you.

For better or worse, video games now exist.

Medicine has gained CAT scans, PET scans, MRIs, lithotripsy, liposuction, laser surgery, robot surgery, and telesurgery. Vaccines for pneumonia, meningitis, hepatitis, HPV, and chickenpox. Ceftriaxone, furosemide, clozapine, risperidone, fluoxetine, ondansetron, omeprazole, naloxone, suboxone, mefloquine, – and for that matter Viagra. Artificial hearts, artificial livers, artificial cochleae, and artificial legs so good that their users can compete in the Olympics. People with artificial eyes can only identify vague shapes at best, but they’re getting better every year.

World population has tripled, in large part due to new agricultural advantages. Catastrophic disasters have become much rarer, in large part due to architectural advances and satellites that can watch the weather from space.

We have a box which you can type something into and it will tell you everything anyone has ever written relevant to your query.

We have a place where you can log into from anywhere in the world and get access to approximately all human knowledge, from the scores of every game in the 1956 Roller Hockey World Cup to 85 different side effects of an obsolete antipsychotic medication. It is all searchable instantaneously. Its main problem is that people try to add so much information to it that its (volunteer) staff are constantly busy deleting information that might be extraneous.

We have the ability to translate nearly major human language to any other major human language instantaneously at no cost with relatively high accuracy.

We have navigation technology that over fifty years has gone from “map and compass” to “you can say the name of your destination and a small box will tell you step by step which way you should be going”.

We have the aforementioned camera, TV, music, videophone, video games, search engine, encyclopedia, universal translator, and navigation system all bundled together into a small black rectangle that fits in your pockets, responds to your spoken natural-language commands, and costs so little that Ethiopian subsistence farmers routinely use them to sell their cows.

But, you tell 1969, we have something more astonishing still. Something even more unimaginable.

“We have,” you say, “people who believe technology has stalled over the past forty-five years.”

1969’s head explodes.