In City Journal, John Tierney looks at the two lethal waves of contagion the world has suffered since 2019, the Wuhan Coronavirus itself and the media-driven panic that almost certainly resulted in far more deaths than the disease that triggered it:

Instead of keeping calm and carrying on, the American elite flouted the norms of governance, journalism, academic freedom — and, worst of all, science. They misled the public about the origins of the virus and the true risk that it posed. Ignoring their own carefully prepared plans for a pandemic, they claimed unprecedented powers to impose untested strategies, with terrible collateral damage. As evidence of their mistakes mounted, they stifled debate by vilifying dissenters, censoring criticism, and suppressing scientific research.

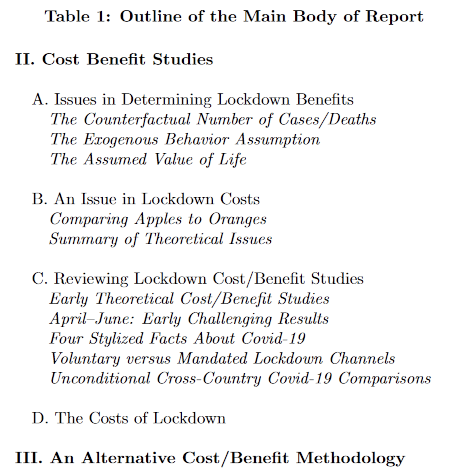

If, as seems increasingly plausible, the coronavirus that causes Covid-19 leaked out of a laboratory in Wuhan, it is the costliest blunder ever committed by scientists. Whatever the pandemic’s origin, the response to it is the worst mistake in the history of the public-health profession. We still have no convincing evidence that the lockdowns saved lives, but lots of evidence that they have already cost lives and will prove deadlier in the long run than the virus itself.

One in three people worldwide lost a job or a business during the lockdowns, and half saw their earnings drop, according to a Gallup poll. Children, never at risk from the virus, in many places essentially lost a year of school. The economic and health consequences were felt most acutely among the less affluent in America and in the rest of the world, where the World Bank estimates that more than 100 million have been pushed into extreme poverty.

The leaders responsible for these disasters continue to pretend that their policies worked and assume that they can keep fooling the public. They’ve promised to deploy these strategies again in the future, and they might even succeed in doing so — unless we begin to understand what went wrong.

The panic was started, as usual, by journalists. As the virus spread early last year, they highlighted the most alarming statistics and the scariest images: the estimates of a fatality rate ten to 50 times higher than the flu, the chaotic scenes at hospitals in Italy and New York City, the predictions that national health-care systems were about to collapse. The full-scale panic was set off by the release in March 2020 of a computer model at the Imperial College in London, which projected that — unless drastic measures were taken — intensive-care units would have 30 Covid patients for every available bed and that America would see 2.2 million deaths by the end of the summer. The British researchers announced that the “only viable strategy” was to impose draconian restrictions on businesses, schools, and social gatherings until a vaccine arrived.

This extraordinary project was swiftly declared the “consensus” among public-health officials, politicians, journalists, and academics. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, endorsed it and became the unassailable authority for those purporting to “follow the science”. What had originally been a limited lockdown — “15 days to slow the spread” — became long-term policy across much of the United States and the world. A few scientists and public-health experts objected, noting that an extended lockdown was a novel strategy of unknown effectiveness that had been rejected in previous plans for a pandemic. It was a dangerous experiment being conducted without knowing the answer to the most basic question: Just how lethal is this virus?

The most prominent early critic was John Ioannidis, an epidemiologist at Stanford, who published an essay for STAT headlined “A Fiasco in the Making? As the Coronavirus Pandemic Takes Hold, We Are Making Decisions Without Reliable Data.” While a short-term lockdown made sense, he argued, an extended lockdown could prove worse than the disease, and scientists needed to do more intensive testing to determine the risk. The article offered common-sense advice from one of the world’s most frequently cited authorities on the credibility of medical research, but it provoked a furious backlash on Twitter from scientists and journalists.