In England all the boasting and flag-wagging, the “Rule Britannia” stuff, is done by small minorities. The patriotism of the common people is not vocal or even conscious. They do not retain among their historical memories the name of a single military victory. English literature, like other literatures, is full of battle-poems, but it is worth noticing that the ones that have won for themselves a kind of popularity are always a tale of disasters and retreats. There is no popular poem about Trafalgar or Waterloo, for instance. Sir John Moore’s army at Corunna, fighting a desperate rear-guard action before escaping overseas (just like Dunkirk!) has more appeal than a brilliant victory. The most stirring battle-poem in English is about a brigade of cavalry which charged in the wrong direction. And of the last war, the four names which have really engraved themselves on the popular memory are Mons, Ypres, Gallipoli and Passchendaele, every time a disaster. The names of the great battles that finally broke the German armies are simply unknown to the general public.

The reason why the English anti-militarism disgusts foreign observers is that it ignores the existence of the British Empire. It looks like sheer hypocrisy. After all, the English have absorbed a quarter of the earth and held on to it by means of a huge navy. How dare they then turn round and say that war is wicked?

It is quite true that the English are hypocritical about their Empire. In the working class this hypocrisy takes the form of not knowing that the Empire exists. But their dislike of standing armies is a perfectly sound instinct. A navy employs comparatively few people, and it is an external weapon which cannot affect home politics directly. Military dictatorships exist everywhere, but there is no such thing as a naval dictatorship. What English people of nearly all classes loathe from the bottom of their hearts is the swaggering officer type, the jingle of spurs and the crash of boots. Decades before Hitler was ever heard of, the word “Prussian” had much the same significance in England as “Nazi” has to-day. So deep does this feeling go that for a hundred years past the officers of the British Army, in peace-time, have always worn civilian clothes when off duty.

George Orwell, “The Lion And The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius”, 1941-02-19.

September 20, 2021

QotD: English jingoism

August 29, 2021

The competing English and Dutch East India companies

In his latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the odd fact that although the Dutch were the last major seafaring power to extend to the East Indies, they quickly became the most powerful European traders and colonialists in the region:

By the mid-seventeenth century, although the trans-Atlantic trades were still almost entirely in the hands of the Spanish, the European trade to the Indian Ocean had come to be dominated by the Dutch — which is quite surprising, as they had arrived so late. The high-value exports of the Indian Ocean — particularly pepper — had anciently arrived via the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, or overland, and then been bought up in Egypt or Syria by the Venetians and Genoese, who then sold them on to the rest of Europe. It was then the Portuguese who had supplanted that trade in the late fifteenth century by discovering the direct route to the Indian Ocean around the Cape of Good Hope. The Portuguese monopolised the new sea route around Africa for a century, almost totally undisturbed by other Europeans, entrenching their position by building forts — occasionally with the permission of local rulers, but often without.

The Portuguese seem to have spread the rumour in Europe that they had effectively conquered the entire region, presumably to dissuade others from even trying to break their monopoly. Even as late as the 1630s, when other nations were already regularly trading there, foreign writers took the time to mock such assertions. As the Welsh-born merchant Lewes Roberts put it, the Portuguese “brag of the conquest of the whole country, which they are in no more possibility entirely to conquer and possess, than the French were to subdue Spain when they possessed of the fort of Perpignan, or the English to be masters of France when they were only sovereigns of Calais.” Quite.

[…]

But for all their tardiness, the Dutch arrival in the Indian Ocean was dramatic. The English may have been the first to threaten the Portuguese monopoly, but in the whole of the 1590s they sent a mere two expeditions out east, and in 1600-10 sent only a further eight (seven by the newly-chartered East India Company (EIC), with a monopoly over English trade with the region, and another voyage licensed to break that monopoly in 1604 by the king, which unhelpfully spoiled the company’s relations with local rulers by turning pirate and plundering Indian and Chinese ships). What the English sent out over the course of twenty years, the Dutch exceeded in just five. Between just 1598 and 1603, after the successful return of de Houtman’s first voyage, they sent out a whopping thirteen fleets — and this despite their merchants not even pooling their efforts like the English had until the very end of that period, when in 1602 the various small and city-based Dutch companies were merged to form a single, national joint-stock monopoly, the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC). The founding of the VOC accelerated the divergence. Between 1613 and 1622 the EIC sent out a paltry 82 ships compared to the VOC’s 201.

The sheer quantity of Dutch ships heading for the Indian Ocean meant that they were soon dominant amongst the European merchants there, capturing forts from the Portuguese, founding further bases of their own, and able to forcibly keep the English out — sometimes by attacking the English directly, other times by simply threatening any of their would-be trading partners. The steady stream of Dutch ships also allowed them to resupply and maintain their factors — the key infrastructure of long-distance commerce, as I explained in last week’s post for subscribers. They were able to have a presence, and project force, in a way that the English could not. By 1638, Lewes Roberts, despite often lauding England’s commercial achievements, and being an EIC official himself, had to concede that in the Indian Ocean “the English nation are the last and least”.

That English weakness was reflected in how EIC merchants had to comport themselves in the region so as to have any share in the trade at all. Despite the EIC’s later reputation for bloodthirsty rapaciousness, in the early seventeenth century they were highly reliant on good relations with the locals. Whereas the Dutch could often afford to use force and bear the repercussions, the English more or less only held on in the early days by ingratiating themselves with local rulers — often by finding common cause against the aggressive and domineering Dutch. The infrequently-supplied English factors were often heavily indebted to local merchants too, including the Indo-Portuguese — a group that they often married into, for access to social networks and support. As the historian David Veevers argues in a new overview of the early EIC (a relatively pricey academic book, but compellingly argued and juicy with detail), the English often went further than just friendliness or integration, subordinating themselves to local rulers too. Of the few early forts that the English managed to establish, for example, that at Madras in 1640 was only built because the local ruler encouraged it, treating the English there as his vassals.

August 27, 2021

The Raid on the Medway – Grand Theft Warship

Drachinifel

Published 24 Apr 2019Today we look at the Dutch raid on the Medway in the 2nd Anglo-Dutch War and its after-effects.

Want to support the channel? – https://www.patreon.com/Drachinifel

Want to talk about ships? https://discord.gg/TYu88mt

Music – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jRQWZ…

Want to get some books? – www.amazon.co.uk/shop/drachinifel

Drydock Episodes in podcast format – https://soundcloud.com/user-21912004

From the comments:

lordmuntague

2 years ago

“On 14 December 1941 a Dutch minelayer named after Jan van Brakel, which was serving as a convoy escort on the UK eastern coast, accidentally hit the anchor buoy of one of the gate vessels which were protecting the entrance to the Medway during World War II. The commander reported this incident to the port authorities, signalling: “Van Brakel damaged boom defence Medway”. The instant reply was: “What, again?”From the RNSA Website.

August 14, 2021

English wholesalers, Dutch retailers and the expansion of foreign trade by European sailors

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the changing nature of English foreign trade as possibly one of the main drivers of the unprecedented growth of London from 1550-1650, and how both English and Dutch sailors differed from most of the rest of Europe:

An English merchant ship of the late 16th to early 17th century: this is a replica of the Susan Constant at the Jamestown Settlement in Virginia. The original ship was built sometime before 1607 and rented by the Virginia Company of London to transport the original settlers to Jamestown.

Photo by Nicholas Russon, March 2004.

I am fairly convinced that this transformation was sparked by the changing nature of England’s trade, with its merchants taking near-total control of it themselves, whereas once they had relied on foreign merchants to bring many of their imports to them. And thanks to their adoption of celestial navigation techniques from the Iberians and Italians — learning to read the stars, to find their latitude at sea — the English gained the ability to discover new routes, noting details down for others to come back again and again and create more permanent new trades. In merchants’ parlance of the time, the English increasingly went in search of “the well head” — to buy things at source, where they were cheapest.

This sounds like the common-sense thing to do. But it was surprisingly rare. Very few countries’ merchants attempted to take advantage of such opportunities for arbitrage — to buy where things were cheapest and sell them where they were most expensive. Even the English themselves, despite their newfound search for well heads, rarely exploited arbitrage opportunities to the full. Although they bought at source, they tended, at first, to sell the goods they’d acquired back in London, to serve English consumers rather than taking them to wherever the goods would sell for the highest prices. This was instead the strategy of the Dutch, whose trading techniques were by 1600 said to surpass all others. Indeed, the Dutch were also some of the only merchants who discriminated on prices within markers, “not shaming to retail any commodity by small parts and parcels”, as one English merchant complained, charging a multitude of buyers according to what they thought they could get from them — something that “both English merchants and Italians disdain to do in any country whatsoever.” It was seemingly considered beneath them.

I’m not wholly clear why the English only sold wholesale when they knew that price discrimination was a Dutch advantage. It seems, at first, to be irrational. But I suspect it had something to do with the wider difficulties of trading abroad. For the English and Dutch were quite unusual in Europe in the early seventeenth century for being among the only merchants willing to risk sailing to shores where their own rulers held no sway.

The Hanseatic merchants of the North Sea and Baltic, who had once been dominant in London, had been stripped of their privileges there and displaced by the English, later confining themselves largely to the Baltic. German mercantile efforts were otherwise generally concentrated inland. And French merchants were apparently under-capitalised, or so the English suspected, because “gentlemen do not meddle with traffic, because they think such traffic ignoble and base”. French merchants did occasionally sail down the Atlantic coast to Spain, and into the Mediterranean to trade with Italy and the Ottoman Empire, but overall they were content to have third parties to come to them — there was always the attraction to foreign merchants of being able to buy French wines, salt, linens, and grain.

As for the once-great Italians, they had apparently been impoverished by the Portuguese discovery of a direct route around Africa to the Indian Ocean, and perhaps by the depredations of various Mediterranean predators too — Algerian corsairs, Ottoman galleys, and the like. Although their rulers could themselves be merchants — the Grand Duke of Tuscany, a Medici, was considered the greatest merchant of them all — by this stage the Italians only rarely ventured far abroad themselves, except over land. Indeed, the English considered them impious for not risking the seas, accusing them of blasphemy for not trusting their lives and livelihoods to God. Whereas the Venetian merchant-nobility had once been required to spend time aboard ship, English commentators by 1600 noticed that their mariners were now overwhelmingly Greek. “Their customs have decayed, their ships rotted and their mariners, the pride of their commonwealth all become poltrones” — that is, loafers or idlers — “and the worst accounted in all those seas”. A Tuscan exploration of the coast of South America in 1608, to look into founding a colony in what is now French Guiana, had to be captained and piloted by Englishmen. What reputation the Italians maintained was as financiers and money-exchangers — perhaps because the Genoese were the only merchants permitted to take the vast quantities of New World silver out of Spain.

July 31, 2021

English sea-borne trade in the early 17th century

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes reviews a book on English trade … a very old book:

I’ve become engrossed this week by a book written in 1638 by the merchant Lewes Roberts — The Marchant’s Mappe of Commerce. It is, in effect, a guide to how to be a merchant, and an extremely comprehensive one too. For every trading centre he could gather information about, Roberts noted the coins that were current, their exchange rates, and the precise weights and measures in use. He set down the various customs duties, down even to the precise bribes you’d be expected to pay to various officials. In Smyrna, for example, Roberts recommended you offer the local qadi some cloth and coney-skins for a vest, the qadi‘s servant some English-made cloth, and their janissary guard a few gold coins.

Unusually for so many books of the period, Roberts was also careful to be accurate. He often noted whether his information came from personal experience, giving the dates of his time in a place, or whether it came second-hand. When he was unsure of details, he recommended consulting with better experts. And myths — like the rumour he heard that the Prophet Muhammad’s remains at Mecca were in an iron casket suspended from the ceiling by a gigantic diamond-like magnet called an adamant — were thoroughly busted. Given his accuracy and care, it’s no wonder that the book, in various revised editions, was in print for almost sixty years after his death. (He died just three years after publication.)

What’s most interesting about it to me, however, is Roberts’s single-minded view of English commerce. The entire world is viewed through the lens of opportunities for trade, taking note of the commodities and manufactures of every region, as well as their principal ports and emporia. A place’s antiquarian or religious tourist sites, which generally make up the bulk of so many other geographical works, are given (mercifully) short shrift. Indeed, because the book was not written with an international audience in mind, it also passes over many trades with which the English were not involved, or from which they were even excluded. It thus provides a remarkably detailed snapshot of what exactly English merchants were interested in and up to on the eve of civil war; and right at the tail end of a century of unprecedented growth in London’s population, itself seemingly led by its expansion of English commerce.

So, what did English merchants consider important? It’s especially illuminating about England’s trade in the Atlantic — or rather, the lack thereof.

Roberts spends remarkably little time on the Americas, which he refers to as the continents of Mexicana (North America) and Peruana (South America). Most of his mentions of English involvement are about which privateers had once raided which Spanish-owned colonies, and he gives especial attention to the seasonal fishing for cod off the coast of Newfoundland — a major export trade to the Mediterranean, and a source of employment to many English West Country farmers, who he refers to as being like otters for spending half their lives on land and the other half on sea.

But as for the recently-established English colonies on the mainland, which Roberts refers to collectively as Virginia, he writes barely a few sentences. Although he reproduces some of the propaganda about what is to be found there — no mention yet of tobacco by the way, with the list consisting largely of foodstuffs, forest products, tar, pitch, and a few ores — the entirety of New England is summarised only as a place “said to be” resorted to by religious dissenters. The island colonies on Barbados and Bermuda were also either too small or too recently established to merit much attention. To the worldly London merchant then, the New World was still peripheral — barely an afterthought, with the two continents meriting a mere 11 pages, versus Africa’s 45, Asia’s 108, and Europe’s 262.

The reason for this was that the English were excluded from trading directly with the New World by the Spanish. It was, as Roberts jealously put it, “shut up from the eyes of all strangers”. The Spanish were not only profiting from the continent’s mines of gold and silver, but he also complained of their monopoly over the export of European manufactures to its colonies there. It’s a striking foreshadowing of what was, in the eighteenth century, to become one of the most important features of the Atlantic economy — the market that the growing colonies would one day provide for British goods. Indeed, Roberts’s most common condemnation of the Spanish was for having killed so many natives, thereby extinguishing the major market that had already been there: “had not the sword of these bloodsuckers ended so many millions of lives in so short a time, trade might have seen a larger harvest”. The genocide had, in Roberts’s view, not only been horrific, but impoverished Europe too (he was similarly upset that the Spanish had slaughtered so many of the natives of the Bahamas, known for the “matchless beauty of their women”).

July 24, 2021

A new history of Anglo-Saxon England

At First Things, Francis Young reviews The Anglo-Saxons: A History of the Beginnings of England by Marc Morris:

The art of telling stories will always be closely associated with the Anglo-Saxons. Beowulf, the era’s best-known epic poem, begins with a word that is difficult to translate, summoning an audience to attention: “Hwæt!” The same word opens another great poem of early medieval England, The Dream of the Rood, in which the wood of the Cross speaks and narrates a uniquely Anglo-Saxon Passion — a reminder that it was the Anglo-Saxons who built Christian England.

These people, as Marc Morris observes, were tellers of tales; and yet, until now, there has been no modern narrative history that weaves together the insights of archaeologists, historians, and literary scholars. Morris has risen to the task, tracing the journey of the English-speaking inhabitants of the island of Britain from tribal warbands to a highly sophisticated medieval kingdom on the eve of the Norman Conquest.

This is a triumph of historical storytelling, woven together from the scattered evidence of archaeology, numismatics, chronicles, charters, and many other sources. The narrative that emerges from these difficult sources is, of course, contentious; after all, even the use of the term “Anglo-Saxon” is now debated by scholars. But the narrative is also compelling, rooted in the primary sources, iconoclastic of received interpretations, and — most importantly — the product of a commanding historical imagination. This is an account of the Anglo-Saxons that will inform our perception of them for years to come.

It would be perfectly possible to challenge virtually every one of the author’s interpretations: As Morris notes, “The less evidence, the more contention,” especially when it comes to the chaotic documentary void of the fifth and sixth centuries. (By comparison, by the mid-eleventh century there is a comparative richness of documentary sources.) The first question is about the nature of Germanic immigration after the departure of the Roman legions at the beginning of the fifth century. Morris leans toward a more traditional “replacement” model in which Germanic settlers took the place of the Britons in the landscape. Morris places a great deal of weight on the linguistic evidence, which shows that Brittonic (the language of the Britons) had little influence on Old English. If the Anglo-Saxons had largely assimilated the Britons, rather than replacing them, we might expect many more Brittonic loanwords.

According to Morris, “The broken Britain that the Saxons found … had no allure.” Post-Roman Britain was “in every sense a degraded society, sifting through the detritus of an earlier civilisation.” Morris follows in the tradition of Bede by viewing the Britons as decadent, but this is by no means the only possible view of post-Roman society. Recent scholarship by Miles Russell and Stuart Laycock has drawn attention to Britain’s failure to become Romanized in the first place, raising the question of whether the abandonment of urban life in the early fifth century should be seen as a sign of decline, and Susan Oosthuizen has argued that rural Britain continued to prosper in the absence of urban settlement; it simply thrived on its own terms as a non-urban society.

July 21, 2021

QotD: The expansion of the English vocabulary (through plundering French)

Because French was at that time the international language of trade, it acted as a conduit, sometimes via Latin, for words from the markets of the East. Arabic words that it then gave to English include: “saffron” (safran), “mattress” (materas), “hazard” (hasard), “camphor” (camphre), “alchemy” (alquimie), “lute” (lut), “amber” (ambre), “syrup” (sirop). The word “checkmate” comes through the French “eschec mat” from the Arabic “Sh h m t“, meaning the king is dead. Again, as with virtue and as with hundreds of the words already mentioned, a word, at its simplest, is a window. In that case, English was perhaps as much threatened by light as by darkness, as much in danger of being blinded by these new revelations as buried under their weight.

Yet the best of English somehow managed to avoid both these fates. It retained its grammar, it held on to its basic words, it kept its nerve, but what it did most remarkably was to accept and absorb French as a layering, not as a replacement but as an enricher. It had begun to do that when Old English met Old Norse: hide/skin; craft/skill. Now it exercised all its powers before a far mightier opponent. The acceptance of the Norse had been limited in terms of vocabulary. Here English was Tom Thumb. But it worked in the same way.

So, a young English hare came to be named by the French word “leveret“, but “hare” was not displaced. Similarly with English “swan”, French “cygnet“. A small English “axe” is a French “hatchet“. “Axe” remained. There are hundreds of examples of this, of English as it were taking a punch but not giving ground.

More subtle distinctions were set in train. “Ask” – English – and “demand” – from French – were initially used for the same purpose but even in the Middle Ages their finer meanings might have differed and now, though close, we use them for markedly different purposes. “I ask you for ten pounds”; “I demand ten pounds”: two wholly different stories. But both words remained. So do “bit” and “morsel”, “wish” and “desire”, “room” and “chamber”. At the time the French might have expected to displace the English. It did not and perhaps the chief reason for that is that people saw the possibilities of increasing clarity of thought, accuracy of expression by refining meaning between two words supposed to be the same. On the surface some of these appear to be interchangeable and sometimes they are. But much more interesting are these fine differences, whose subtleties increase as time carries them first a hair’s breadth apart and then widens the gap, multiplies the distinctions: just as “ask” has evolved far away from “demand”.

Not only did they drift apart but something else happened which demonstrates how deeply not only history but class is buried in language. You can take an (English) “bit” of cheese and most people do. If you want to use a more elegant word you take a (French) “morsel” of cheese. It is undoubtedly thought to be a better class of word and yet “bit”, I think, might prove to have more stamina. You can “start” a meeting or you can “commence” a meeting. Again, “commence” carries a touch more cultural clout though “start” has the better sound and meaning to it for my ear. But it was the embrace which was the triumph, the coupling which was never quite one.

That’s the beauty of it. That was the sweet revenge which English took on French: it not only anglicised it, it used the invasion to increase its own strength; it looted the looters, plundered those who had plundered, out of weakness brought forth strength. For “answer” is not quite “respond”; now they have almost independent lives. “Liberty” isn’t always “freedom”. Shades of meaning, representing shades of thought, were massively absorbed into our language and our imagination at that time. It was new lamps and old; both. The extensive range of what I would call “almost synonyms” became one of the glories of the English language, giving it astonishing precision and flexibility, allowing its speakers and writers over the centuries to discover what seemed to be exactly the right word.

Rather than replace English, French was being brought into service to help enrich and equip it for the role it was on its way to reassuming.

Melvyn Bragg, The Adventure of English, as quoted by Brian Micklethwait, “Melvyn Bragg on England’s verbal twins”, Samizdata, 2018-12-23.

July 18, 2021

QotD: Rules of wars in the Eighteenth Century

Although the Succession of Wars went on nearly the whole time in the eighteenth century, the countries kept on making a treaty called the Treaty of Paris (or Utrecht).

This Treaty was a Good Thing and laid down the Rules for fighting the wars; these were:

(1) that there should be a mutual restitution of conquests except that England should keep Gibraltar, Malta, Minorca, Canada, India, etc.;

(2) that France should hand over to England the West Indian islands of San Flamingo, Tapioca, Sago, Dago, Bezique and Contango, while the Dutch were always to have Lumbago and the Laxative Islands;

(3) that everyone, however Infantile or even insane, should renounce all claim to the Spanish throne;

(4) that the King (or Queen) of France should admit that the King (or Queen) of England was King (or Queen) of England and should not harbour the Young Pretender, but that the fortifications of Dunkirk should be disgruntled and raised to the ground.

Thus, as soon as the fortifications of Dunkirk had been gruntled again, or the Young Pretender was found in a harbour in France, or it was discovered that the Dutch had not got Lumbago, etc., the countries knew that it was time for the treaty to be signed again, so that the War could continue in an orderly manner.

W.C. Sellar & R.J. Yeatman, 1066 And All That, 1930.

July 16, 2021

The lure of London and agricultural specialization in post-Black Death England

In the latest edition of his Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes outlines the “push” and “pull” theories to account for the vast growth of London and how that urban growth strongly encouraged specialization in English agriculture to feed the great city:

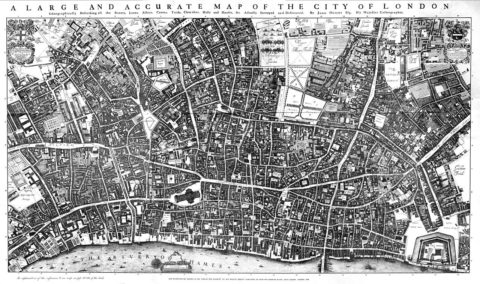

The 1677 original of this map is 8 feet 5 inches by 4 feet 7 inches, in 20 sheets. In 1894 the British Museum granted permission to the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society to make a reduced copy, of which the original of this scan is a copy. The L&M Society copy apparently did not match the dissected sheets perfectly, and the misjoins can be seen in places in this reproduction.

Scanned copy of reproduction in Maps of Old London (1908) of Ogilby & Morgan’s Map of London.

Something significant happened to the English countryside in the century before 1650. Although England’s population merely recovered to its pre-Black Death high of about 5 million, the economy was transformed. Having once been an overwhelmingly agrarian society, by 1650 a small but unprecedented proportion of the population now lived in cities, and less than half of the workforce was employed in agriculture. The country had de-agrarianised, and most remarkably of all, its food was still grown at home.

[…]

One possibly explanation is that there was some special change in England’s agricultural technology that increased its productivity, requiring fewer and fewer people, and possibly even driving them off the land, so that they were forced to find alternative employment. This thesis comes in various forms, many of which I’m still coming to grips with, but broadly speaking it implies a “push” from the fields, and into industry and the cities. Desperate, and unable to demand high wages, these cheaper workers should have stimulated industry’s growth.

The alternative, however, is that there was nothing very special or innovative about English agriculture, and that instead there was an even larger increase in the demand for workers in industry and services. The thesis implies a “pull” into industry and the cities, causing people to abandon agriculture for more profitable pursuits, and thereby making England’s agriculture de facto more productive — something that may or may not have actually been accompanied by any changes to agricultural technology, depending on how much slack there was in how the labourers or land had been employed.

The push thesis implies agricultural productivity was an original cause of England’s structural transformation; the pull thesis that it was a result. The evidence, I think, is in favour of a pull — specifically one caused by the dramatic growth of London’s trade.

Even though the population eventually recovered from the massive impact of the Black Death, not all of the land that was under plough was returned to active farming and a much greater diversity of uses for rural land emerged, including more pastures for grazing livestock, and small cash crops to be sold into the cities (especially into London).

With the dramatic growth of London in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the more intensive methods came to be in much higher demand. Indeed, the extraordinary pull of the city’s growth resulted in English agriculture becoming increasingly specialised. Not only were there millions of acres of pasture still left that could be returned to the plough, but despite the relative fall in the prices of livestock, some areas actually became even more devoted to pasture. Many of the villages that had been abandoned after the Black Death were, even by the 1870s, over half a millennium later, still not being farmed. With wealthy Londoners demanding more varied diets, with meat and dairy, the various regions of England discovered their comparative advantages rather than all shifting to grain. There was thus extra room for agriculture to become more productive simply by devoting the best land for pasture to pasture, and the best soils for arable to arable, then trading the produce with one another, rather than have each area try to be self-sufficient. It’s something we also see in the decline of grains like rye, especially near London, to be replaced by wheat — the switching of a crop best-suited to local subsistence, to one that could be sold elsewhere and in bulk for cash.

In general, the south and east of England became increasingly arable, while the north-west concentrated on pasture. Yet there were also exceptions to be made for London’s particular wants. Thus, county Durham converted more land to arable to feed the miners of Newcastle coal, used to heat London’s homes; and the county of Middlesex, now largely disappeared under London’s own expansion, specialised in pasture for horses, rather than feeding people, so as to feed the city’s main sources of transportation. As the writer Daniel Defoe put it in the 1720s, “this whole Kingdom, as well the people, as the land, and even the sea, in every part of it, are employed to furnish something, and I may add, the best of everything, to supply the city of London with provisions.”

July 11, 2021

QotD: William and Mary

Williamanmary for some reason was known as The Orange in their own country of Holland, and were popular as King of England because the people naturally believed it was descended from Nell Glyn. It was on the whole a good King and one of their first Acts was the Toleration Act, which said they would tolerate anything, though afterwards it went back on this and decided that they could not tolerate the Scots.

A Darien Scheme

The Scots were now in a skirling uproar because James II was the last of the Scottish Kings and England was under the rule of the Dutch Orange; it was therefore decided to put them in charge of a very fat man called Cortez and transport them to a Peak in Darien, where it was hoped they would be more silent.

Massacre of Glascoe

The Scots, however, continued to squirl and hoot at the Orange, and a rebellion was raised by the memorable Viscount Slaughterhouse (the Bonnie Dundee) and his Gallivanting Army. Finally Slaughterhouse was defeated at the Pass of Ghilliekrankie and the Scots were all massacred at Glascoe, near Edinburgh (in Scotland, where the Scots were living at that time); after which they were forbidden to curl or hoot or even to wear the Kilt. (This was a Good Thing, as the Kilt was one of the causes of their being so uproarious and Scotch.)

Blood-Orangemen

Meanwhile the Orange increased its popularity and showed themselves to be a very strong King by its ingenious answer to the Irish Question; this consisted in the Battle of the Boyne and a very strong treaty which followed it, stating (a) that all the Irish Roman Catholics who liked could be transported to France, (b) that all the rest who liked could be put to the sword, (c) that Northern Ireland should be planted with Blood Orangemen.

These Blood-Orangemen are still there; they are, of course, all descendants of Nell Glyn and are extremely fierce and industrial and so loyal that they are always ready to start a loyal rebellion to the Glory of God and the Orange. All of which shows that the Orange was a Good Thing, as well as being a good King. After the Treaty the Irish who remained were made to go and live in a bog and think of a New Question.

The Bank of England

It was Williamanmary who first discovered the National Debt and had the memorable idea of building the Bank of England to put it in. The National Debt is a very Good Thing and it would be dangerous to pay it off, for fear of Political Economy.

Finally the Orange was killed by a mole while out riding and was succeeded by the memorable dead queen, Anne.

W.C. Sellar & R.J. Yeatman, 1066 And All That, 1930.

June 30, 2021

QotD: The Yorkist pretenders

English History has always been subject to Waves of Pretenders. These have usually come in small waves of about two — an Old Pretender and a Young Pretender, their object being to sow dissension in the realm, and if possible to contuse the Royal issue by pretending to be heirs to the throne.

Two Pretenders who now arose were Lambert Simnel and Perkin Warbeck, and they succeeded in confusing the issue absolutely by being so similar that some historians suggest they were really the same person (i.e. the Earl of Warbeck).

Lambert Simnel (the Young Pretender) was really (probably) himself, but cleverly pretended to be the Earl of Warbeck. Henry VII therefore ordered him to be led through the streets of London to prove that he really was.

Perkin Warbeck (the Older and more confusing Pretender) insisted that he was himself, thus causing complete dissension till Henry VII had him led through the streets of London to prove that he was really Lambert Simnel.

The punishment of these memorable Pretenders was justly similar, since Perkin Warmnel was compelled to become a blot on the King’s skitchen, while Perbeck was made an escullion. Wimneck, however, subsequently began pretending again. This time he pretended that he had been smothered in early youth and buried under a stair-rod while pretending to be one of the Little Princes in the Tower. In order to prove that he had not been murdered before, Henry was reluctantly compelled to have him really executed.

Even after his execution many people believed that he was only pretending to have been beheaded, while others declared that it was not Warmneck at all but Lamkin, and that Permnel had been dead all the time really, like Queen Anne.

W.C. Sellar & R.J. Yeatman, 1066 And All That, 1930.

June 28, 2021

Pounds, shillings, and pence: a history of English coinage

Lindybeige

Published 18 Dec 2020I talk for a bit the history of English coinage, and the problems of maintaining a good currency. Once or twice I might stray off topic, but I end with an explanation of why the system worked so well.

Picture credits:

40 librae weight

Martinvl, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…, via Wikimedia CommonsSceat K series, and others

By Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…William I penny, and Charles II crown

The Portable Antiquities Scheme/ The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…, via Wikimedia CommonsBust of Charlemagne

By Beckstet – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…Edward VI crown

By CNG – http://www.cngcoins.com/Coin.aspx?Coi…, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…Charles II guinea

Gregory Edmund, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…, via Wikimedia CommonsSupport me on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/Lindybeige

Buy the music – the music played at the end of my videos is now available here: https://lindybeige.bandcamp.com/track…

Buy tat (merch):

https://outloudmerch.com/collections/…Lindybeige: a channel of archaeology, ancient and medieval warfare, rants, swing dance, travelogues, evolution, and whatever else occurs to me to make.

▼ Follow me…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Lindybeige I may have some drivel to contribute to the Twittersphere, plus you get notice of uploads.

My website:

http://www.LloydianAspects.co.uk

June 8, 2021

QotD: Magna Carta

There also happened in this reign the memorable Charta, known as Magna Charter on account of the Latin Magna (great) and Charter (a Charter); this was the first of the famous Chartas and Gartas of the Realm and was invented by the Barons on a desert island in the Thames called Ganymede. By congregating there, armed to the teeth, the Barons compelled John to sign the Magna Charter, which said:

- That no one was to be put to death, save for some reason (except the Common People).

- That everyone should be free (except the Common People).

- That everything should be of the same weight and measure throughout the Realm (except the Common People).

- That the Courts should be stationary, instead of following a very tiresome medieval official known as the King’s Person all over the country.

- That “no person should be fined to his utter ruin” (except the King’s Person).

- That the Barons should not be tried except by a special jury of other Barons who would understand.

Magna Charter was therefore the chief cause of Democracy in England, and thus a Good Thing for everyone (except the Common People).

After this King John hadn’t a leg to stand on and was therefore known as `John Lackshanks’.

W.C. Sellar & R.J. Yeatman, 1066 And All That, 1930.

June 3, 2021

QotD: Simon de Montfort

While he was in the Tower, Henry III wrote a letter to the nation saying that he was a Good Thing. This so confused the Londoners that they armed themselves with staves, jerkins, etc., and massacred the Jews in the City. Later, when he was in the Pope’s Bosom, Henry further confused the People by presenting all the Bonifaces of the Church to Italians. And the whole reign was rapidly becoming less and less memorable when one of the Barons called Simon de Montfort saved the situation by announcing that he had a memorable Idea.

Simon de Montfort’s Good Idea

Simon de Montfort’s Idea was to make the Parliament more Representative by inviting one or two vergers, or vergesses, to come from every parish, thus causing the only Good Parliament in History. Simon de Montfort, though only a Frenchman, was thus a Good Thing, and is very notable as being the only good Baron in history. The other Barons were, of course, all wicked Barons. They had, however, many important duties under the Banorial system. These were:

- To be armed to the teeth.

- To extract from the Villein(*) Saccage and Soccage, tollage and tallage, pillage and ullage, and, in extreme cases, all other banorial amenities such as umbrage and porrage. (These may be collectively defined as the banorial rites of carnage and wreckage).

- To hasten the King’s death, deposition, insanity, etc., and make quite sure that there were always at least three false claimants to the throne.

- To resent the Attitude of the Church. (The Barons were secretly jealous of the Church, which they accused of encroaching on their rites — see p. 30, Age of Piety.)

- To keep up the Middle Ages.

(*) Villein: medieval term for agricultural labourer, usually suffering from scurvy, Black Death, etc.

W.C. Sellar & R.J. Yeatman, 1066 And All That, 1930.

May 31, 2021

The History of HSTs in the West

Ruairidh MacVeigh

Published 29 May 2021Hello again!

With the recent withdrawal of the last HST operations into London, I wanted to make a series of videos chronicling the history of these mighty trains in terms of their years of each region they were assigned to, the Great Western, East Coast, Midland, West Coast and Cross Country Routes.

With that in mind, we start with the first of the BR Regions to employ the venerable HST, but also the first to withdraw them from long distance services, the Great Western, a line that, since its inception under the auspices of Brunel, has played host to many different types of trains, but none have had greater impact that the superb HSTs.

All video content and images in this production have been provided with permission wherever possible. While I endeavour to ensure that all accreditations properly name the original creator, some of my sources do not list them as they are usually provided by other, unrelated YouTubers. Therefore, if I have mistakenly put the accreditation of “Unknown”, and you are aware of the original creator, please send me a personal message at my Gmail (this is more effective than comments as I am often unable to read all of them): rorymacveigh@gmail.com

The views and opinions expressed in this video are my personal appraisal and are not the views and opinions of any of these individuals or bodies who have kindly supplied me with footage and images.

If you enjoyed this video, why not leave a like, and consider subscribing for more great content coming soon.

Thanks again, everyone, and enjoy!

References:

– 125Group (and their respective sources)

– Wikipedia (and its respective references)